6 Intersecting Spheres of Legality and Illegality | Considered Legitimate by Border Communities Back in Control of Their Traditional Forests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tantangan Dari Dalam : Otonomi Redaksi Di 4 Media Cetak Nasional ; Kompas, Koran Tempo, Media Indonesia, Republika

Tantangan dari Dalam Otonomi Redaksi di 4 Media Cetak Nasional: Kompas, Koran Tempo, Media Indonesia, Republika Penulis : Anett Keller Jakarta, 2009 i Tantangan dari Dalam TANTANGAN DARI DALAM Otonomi Redaksi di 4 Media Cetak Nasional: Kompas, Koran Tempo, Media Indonesia, Republika Diterbitkan Oleh: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES) Indonesia Office ISBN: xxx Penulis: Anett Keller Design Cover : Arganta Arter Dicetak oleh : CV Dunia Printing Selaras (d’print comm) Edisi Pertama, Agustus 2009 Dilarang memperbanyak atau mengutip sebagian atau seluruh isi buku ini dalam bentuk apapun tanpa izin tertulis dari FES Indonesia Office ii Daftar Isi Daftar Isi ........................................................................... iii Kata Pengantar Penulis .................................................... vi Kata Pengantar Direktur Perwakilan Friedrich Ebert Stiftung Indonesia ................................................................ xiii Kata Pengantar Direktur Eksekutif Lembaga Studi Pers xvii & Pembangunan ................................................................ Tentang Penulis .................................................................... xxiii Tentang Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES) ............................ xxiv Abstraksi ........................................................................... xxv Satu Pendahuluan 1. Pendahuluan ……………………………………..... 1 Dua Latar Belakang Teori 2. Latar Belakang Teori .............................................. 5 2.1. Pasar versus Kewajiban Umum .............. 5 2.2. Tekanan -

The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance

Policy Studies 23 The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance Marcus Mietzner East-West Center Washington East-West Center The East-West Center is an internationally recognized education and research organization established by the U.S. Congress in 1960 to strengthen understanding and relations between the United States and the countries of the Asia Pacific. Through its programs of cooperative study, training, seminars, and research, the Center works to promote a stable, peaceful, and prosperous Asia Pacific community in which the United States is a leading and valued partner. Funding for the Center comes from the U.S. government, private foundations, individuals, cor- porations, and a number of Asia Pacific governments. East-West Center Washington Established on September 1, 2001, the primary function of the East- West Center Washington is to further the East-West Center mission and the institutional objective of building a peaceful and prosperous Asia Pacific community through substantive programming activities focused on the theme of conflict reduction, political change in the direction of open, accountable, and participatory politics, and American understanding of and engagement in Asia Pacific affairs. The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance Policy Studies 23 ___________ The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance _____________________ Marcus Mietzner Copyright © 2006 by the East-West Center Washington The Politics of Military Reform in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Elite Conflict, Nationalism, and Institutional Resistance by Marcus Mietzner ISBN 978-1-932728-45-3 (online version) ISSN 1547-1330 (online version) Online at: www.eastwestcenterwashington.org/publications East-West Center Washington 1819 L Street, NW, Suite 200 Washington, D.C. -

Parental Expectations and Young People's Migratory

Jurnal Psikologi Volume 44, Nomor 1, 2017: 66 - 79 DOI: 10.22146/jpsi.26898 Parental Expectations and Young People’s Migratory Experiences in Indonesia Wenty Marina Minza1 Center for Indigenous and Cultural Psychology Faculty of Psychology Universitas Gadjah Mada Abstract. Based on a one-year qualitative study, this paper examines the migratory aspirations and experiences of non-Chinese young people in Pontianak, West Kalimantan, Indonesia. It is based on two main questions of migration in the context of young people’s education to work transition: 1) How do young people in provincial cities perceive processes of migration? 2) What is the role of intergenerational relations in realizing these aspirations? This paper will describe the various strategies young people employ to realize their dreams of obtaining education in Java, the decisions made by those who fail to do so, and the choices made by migrants after the completion of their education in Java. It will contribute to a body of knowledge on young people’s education to work transitions and how inter-generational dynamics play out in that process. Keywords: intergenerational relation; migratory aspiration; youth Internal1 migration plays a key role in older generation in Pontianak generally mapping mobility patterns among young associate Java with ideas of progress, people, as many young people continue to opportunities for social mobility, and the migrate within their home country (Argent success of inter-generational reproduction & Walmsley, 2008). Indonesia is no excep- or regeneration. Yet, migration involves tion. The highest participation of rural various negotiation processes that go urban migration in Indonesia is among beyond an analysis of push and pull young people under the age of 29, mostly factors. -

Captures Asean

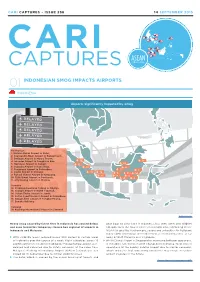

CARI CAPTURES • ISSUE 236 14 SEPTEMBER 2015 CARI ASEAN CAPTURES REGIONAL 01 INDONESIAN SMOG IMPACTS AIRPORTS INDONESIA Airports Significantly Impacted by Smog DELAYED DELAYED DELAYED DELAYED DELAYED Kalimantan 1. Melalan Melak Airport in Kutai, 2. Syansyudin Noor Airport in Banjarmasin, 3. Beringin Airport in Muara Teweh, 4. Iskandar Airport in Pangkalan Bun 13 11 5. Haji Asan Airport in Sampit, 12 18 6. Supadio Airport in Kubu Raya, 14 8 7. Pangsuma Airport in Putussibau, 7 1 8. Susilo Airport in Sintang, 15 16 6 3 10 9. Rahadi Usman Airport in Ketapang, 17 9 5 10. Tjilik Riwut Airport in Pontianak, 4 2 11. Atty Besing Airport in Malinau. Sumatra 12. Ferdinand Lumban Tobing in Sibolga, 13. Silangit Airport in North Tapanuli, 14. Sultan Thaha Airport in Jambi, 15. Sultan Syarif Kasim II Airport in Pekanbaru, 16. Depati Amir Airport in Pangkal Pinang, 17. Bangka Belitung Sarawak 18. Kuching International Airport in Sarawak Antara News Heavy smog caused by forest fires in Indonesia has caused delays peat bogs to clear land in Indonesia, has seen some 400 wildfire and even forced the temporary closure two regional of airports in hotspots over the course of the past month alone according to the Indonesia and Malaysia. NOAA-18 satellite; furthermore, severe and unhealthy Air Pollutant Index (API) recordings were observed at several locations as far With visibility levels reduced below 800 meters in certain areas away as East Malaysia and Singapore of Indonesia over the course of a week, flight schedules across 16 Whilst Changi Airport in Singapore -

Laporan Kinerja Badan Geologi Tahun 2014

LAPORAN KINERJA BADAN GEOLOGI TAHUN 2014 BADAN GEOLOGI KEMENTERIAN ENERGI DAN SUMBER DAYA MINERAL Tim Penyusun: Oman Abdurahman - Priatna - Sofyan Suwardi (Ivan) - Rian Koswara - Nana Suwarna - Rusmanto - Bunyamin - Fera Damayanti - Gunawan - Riantini - Rima Dwijayanti - Wiguna - Budi Kurnia - Atep Kurnia - Willy Adibrata - Fatmah Ughi - Intan Indriasari - Ahmad Nugraha - Nukyferi - Nia Kurnia - M. Iqbal - Ivan Verdian - Dedy Hadiyat - Ari Astuti - Sri Kadarilah - Agus Sayekti - Wawan Bayu S - Irwana Yudianto - Ayi Wahyu P - Triyono - Wawan Irawan - Wuri Darmawati - Ceme - Titik Wulandari - Nungky Dwi Hapsari - Tri Swarno Hadi Diterbitkan Tahun 2015 Badan Geologi Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral Jl. Diponegoro No. 57 Bandung 40122 www.bgl.esdm.go.id Pengantar Geologi merupakan salah satu pendukung penting dalam program pembangunan nasional. Untuk program tersebut, geologi menyediakan informasi hulu di bidang En- ergi dan Sumber Daya Mineral (ESDM). Di samping itu, kegiatan bidang geologi juga menyediakan data dan informasi yang diperlukan oleh berbagai sektor, seperti mitigasi bencana gunung api, gerakan tanah, gempa bumi, dan tsunami; penataan ruang, pemba- ngunan infrastruktur, pengembangan wilayah, pengelolaan air tanah, dan penyediaan air bersih dari air tanah. Pada praktiknya, pembangunan kegeologian di tahun 2014 masih menghadapi beber- apa isu strategis berupa peningkatan kualitas hidup masyarakat Indonesia mencapai ke- hidupan yang sejahtera, aman, dan nyaman mencakup ketahanan energi, lingkungan dan perubahan iklim, bencana alam, tata ruang dan pengembangan wilayah, industri mineral, pengembangan informasi geologi, air dan lingkungan, pangan, dan batas wilayah NKRI (kawasan perbatasan dan pulau-pulau terluar). Ketahanan energi menjadi isu utama yang dihadapi sektor ESDM, sekaligus menjadi yang dihadapi oleh Badan Geologi yang mer- upakan salah satu pendukung utama bagi upaya-upaya sektor ESDM. -

Hak Cipta Dan Penggunaan Kembali: Lisensi Ini Mengizinkan Setiap Orang Untuk Menggubah, Memperbaiki, Dan Membuat Ciptaan Turunan

Hak cipta dan penggunaan kembali: Lisensi ini mengizinkan setiap orang untuk menggubah, memperbaiki, dan membuat ciptaan turunan bukan untuk kepentingan komersial, selama anda mencantumkan nama penulis dan melisensikan ciptaan turunan dengan syarat yang serupa dengan ciptaan asli. Copyright and reuse: This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon work non-commercially, as long as you credit the origin creator and license it on your new creations under the identical terms. Team project ©2017 Dony Pratidana S. Hum | Bima Agus Setyawan S. IIP BAB II GAMBARAN UMUM PERUSAHAAN 2.1 Profil Perusahaan Berikut ini adalah sejarah, visi, misi, logo, motto, profil pembaca, dan struktur redaksi yang penulis ambil dari company profile milik Suara Pembaruan yang penulis dapatkan dari divisi Human Resource Development perusahaan. 2.1.1 Sejarah Suara Pembaruan Sejarah Suara Pembaruan tidak lepas dengan Sinar Harapan. Suara Pembaruan merupakan media yang berdiri pada 4 Februari 1987. Suara Pembaruan didirikan karena adanya pembredelan terhadap koran sore harian Sinar Harapan. Saat itu Sinar Harapan yang terbit pada sore hari banyak berisi yang bersikap kritis terhadap pemerintahan. Sinar Harapan memiliki kebijakan redaksi untuk netral, kritis, dan jujur. Akibatnya Sinar Harapan mendapat hukuman dari pemerintah yaitu tiga kali mendapat surat penutupan atau tidak boleh terbit. Pada 9 Oktober 1986 pihak menteri penerangan mencabut Surat Izin Usaha Penerbitan Pers (SIUPP) Sinar Harapan sebab dilihat berlawanan dengan aturan pemerintah di bidang penertiban (Rahzen, 2007: 276 ). Ada pergantian nama penerbit dari PT Sinar Kasih menjadi PT Media Interaksi Utama. SP berdiri sesuai SK Menpen RI Nomor 224/SK/MENPEN/A.7/1987 dengan alamat redaksi di Jalan Dewi Sartika Nomor 136 D Jakarta 13630. -

Traditional Knowledge, Perceptions and Forest Conditions in a Dayak Mentebah Community, West Kalimantan, Indonesia

WORKING PAPER Traditional knowledge, perceptions and forest conditions in a Dayak Mentebah community, West Kalimantan, Indonesia Edith Weihreter Working Paper 146 Traditional knowledge, perceptions and forest conditions in a Dayak Mentebah community, West Kalimantan, Indonesia Edith Weihreter Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) Working Paper 146 © 2014 Center for International Forestry Research Content in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0), http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Weihreter E. 2014. Traditional knowledge, perceptions and forest conditions in a Dayak Mentebah community, West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Working Paper 146. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR. Photo by Edith Weihreter/CIFOR Nanga Dua Village on Penungun River with canoes and a gold digging boat CIFOR Jl. CIFOR, Situ Gede Bogor Barat 16115 Indonesia T +62 (251) 8622-622 F +62 (251) 8622-100 E [email protected] cifor.org We would like to thank all donors who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Fund. For a list of Fund donors please see: https://www.cgiarfund.org/FundDonors Any views expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of CIFOR, the editors, the authors’ institutions, the financial sponsors or the reviewers. You have your way. I have my way. As for the right way, the correct way, and the only way, it does not exist. FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE Table of content List of abbreviations vi Acknowledgments vii 1 Introduction -

Bab I Pendahuluan

1 BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Kompetisi bisnis media cetak khususnya di Provinsi Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta (untuk seterusnya cukup ditulis DIY) terbilang cukup ketat. Hal itu menyebabkan kolapsnya sejumlah perusahaan media cetak sehingga tidak terbit lagi. Namun pada sisi lain hal itu memunculkan surat kabar baru yang hadir di tengah masyarakat. Sewaktu peneliti masih dalam tahap penggalian data penelitian tesis ini, surat kabar Jogjakarta Post—yang berafiliasi dengan Jateng Pos, yang dulunya merupakan “reinkarnasi” dari koran kuning (yellow newspaper) Meteor milik Jawa Pos Group; pada akhir tahun 2013 sudah tidak terbit lagi di DIY. Hanya tinggal Jateng Pos-Meteor saja yang sampai kini tetap terbit hanya di kawasan Jawa Tengah saja. Sebelumnya nasib serupa (gulung tikar) juga menimpa Harian Pagi Jogja Raya milik Jawa Pos Group yang berkantor di DIY pada tahun 2011. Selain itu KR Bisnis milik KR Group yang sebelumnya bernama Koran Merapi mulai tidak terbit pada 2 Januari 2010. Pihak manajemen KR Group lebih memilih menerbitkan kembali Koran Merapi edisi terbaru bernama Koran Merapi Pembaruan. Perusahaan surat kabar lain yang kolaps di DIY yaitu Malioboro Ekspress (surat kabar 2 mingguan) yang pernah dipimpin oleh Sutirman Eka Ardhana1 sudah tidak terbit lagi pada tahun 2010. Sampai pertengahan Januari 2014, tercatat ada tujuh perusahaan surat kabar harian dan mingguan yang berkantor di DIY. Berbagai surat kabar harian dan mingguan tersebut adalah Kedaulatan Rakyat, Radar Jogja, Bernas Jogja, Koran Merapi Pembaruan, Harian Jogja, Harian Pagi Tribun Jogja, dan Minggu Pagi. Berdasarkan hasil pengamatan langsung di lapangan, di samping terdapat sebaran koran lokal, DIY juga menjadi ekspansi dari surat kabar lokal dan nasional dari luar daerah. -

Kata Pengantar

This first edition published in 2007 by Tourism Working Group Kapuas Hulu District COPYRIGHT © 2007 TOURISM WORKING GROUP KAPUAS HULU DISTRICT All Rights Reserved, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted to any form or by any means, electronic, mecanical, photo-copying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright owners. CO-PUBLISHING MANAGER : Hermayani Putera, Darmawan Isnaini HEAD OF PRODUCTION : Jimmy WRITER : Anas Nasrullah PICTURES TITLE : Jean-Philippe Denruyter ILUSTRATOR : Sugeng Hendratno EDITOR : Syamsuni Arman, Caroline Kugel LAYOUT AND DESIGN : Jimmy TEAM OF RESEARCHER : Hermas Rintik Maring, Anas Nasrullah, Rudi Zapariza, Jimmy, Ade Kasiani, Sugeng Hendratno. PHOTOGRAPHIC CREDITS Sugeng Hendratno: 1, 2BL, 2BR, 4B, 5L, 6, 7, 14A, 14BR, 21R, 21BL, 22B, 26L, 27T, 27A, 30, 33, 35, 40AL, 40AR, 43A, 43BR, 46T, 51, 54BL, 55B, 58BL, 58BR, 64BR, 66A, 67A, 68, 72B, 75A, 76L, 77BL, 77BR, 78, 79BL, 80L, 83B, 84B, 85B, 90B, 94L, 94B, 94A, 99L, 102BL, 103M1, 103M3, 103M5, 103R3, 103R6, 104L1, 104M2, 105L3, 105L4, 105M3, 105R1, 105R3, 105R4, Jimmy: 2A, 3A, 3L, 4T, 5B, 13L, 14R, 14BL, 15, 16 AL, 16 AR, 16B, 17A, 18T, 18R, 18BL, 18BR, 19, 20, 21T, 21BR, 22T, 22A, 23AL, 24, 25, 32BL, 32BR, 40T, 40L, 42, 43BL, 44 All, 45 All, 47, 48, 49, 50 All, 52, 53L, 54BR, 55T, 57TR, 57B, 59 All, 61AL, 62, 64BL, 66R, 69A, 69BL, 69BR, 70 All, 71AL, 71AR, 71BL, 71BR, 72A, 74, 75B, 76B, 79A, 79BR, 80B, 81, 83, 84L, 85AL, 85AR, 87 All, 88, 89, 90AL, 90AR, 90M, 92, 93 All, 98B, 99B, -

Cross-Border Correlation of Geological Formations in Sarawak and Kalimantan

Geol. Soc. Malaysia, Bulletin 28, November 1991; pp. 63 - 95 Cross-border correlation of geological formations in Sarawak and Kalimantan ROBERT B. TATE Dept. of Geology University of Malaya 59100 Kuala Lumpur. Abstract: Recent geological mapping by an AustralianlIndonesian team in West and Central Kalimantan has resulted in a revised stratigraphy for the Paleozoic-Tertiary igneous and sedimentary successions in terms of (1) Continental Basement and Platform (ShelO Sedimentary rocks, (2) Continental Arc intrusives and volcanics, (3) Oceanic Basement and overlying sedimentary rocks and (4) Foreland Rocks (Post-tectonic igneous rocks and sedimentary basins, (5) Tectonic melange and (6) Surficial deposits. Correlation charts are presented to reconcile the stratigraphy across the international border between Sarawak, East Malaysia, and Kalimantan, Indonesia. INTRODUCTION The stratigraphy of Central and West Kalimantan has been described recently by Pieters et al. (1987), Pieters & Supriatna (1989a) and Williams et al. (1988), and for West Sarawak by Tan (1986). All authors have correlated certain individual stratigraphic formations, particularly where they are common to both Sarawak and Kalimantan but no detailed cross-border correlation has been presented to date. This paper attempts to provide a regional correlation between Central and Northwest Kalimantan and South and West Sarawak (Table 1) and, as a result of the new data, to indicate fundamental changes to the interpretation of the geology of this part of Borneo. The completed Indonesian-Australian Geological Mapping Project (IAGMP) covers an area of some 850 km long and 250-300 km wide in Central and West Kalimantan (Pieters & Supriatna, 1989b); twelve preliminary geological maps at 1: 250,000 scale (see key to Fig.l) and a 1:1 million compilation map are published and one 1:250,000 map is in preparation. -

Inaugural Indonesia-Australia Dialogue 4-6 October 2011

Australian Institute of International Affairs Inaugural Indonesia-Australia Dialogue 4-6 October 2011 Jointly organised by Australian Institute of International Affairs and the Centre for Strategic and International Studies Supported by Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australia and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Indonesia Australian Institute of International Affairs Outcomes Report The inaugural Indonesia-Australia Dialogue was held in Jakarta from 4-6 October 2011. The Indonesia-Australia Dialogue initiative was jointly announced by leaders during the March 2010 visit to Australia by Indonesian President Yudhoyono as a bilateral second track dialogue to enhance people-to-people links between the two countries. The inaugural Indonesia-Australia Dialogue was co- convened by Mr John McCarthy, AIIA National President and former Ambassador to Indonesia, and Dr Rizal Sukma, Executive Director of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies. The AIIA was selected by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade to act as secretariat for the Dialogue. Highlights of the Dialogue included: Participation by an impressive Australian delegation including politicians, senior academic and media experts as well as leaders in business, science and civil society. Two days of Dialogue held in an atmosphere of open exchange with sharing of expertise and insights at a high level among leading Indonesian and Australian figures. Messages from Prime Minister Gillard and Minister for Foreign Affairs Rudd officially opening the Dialogue. Opening attended by Australian Ambassador to Indonesia HE Mr Greg Moriarty and Director General of Asia Pacific and African Affairs HE Mr Hamzah Thayeb. Meeting with Indonesia’s Foreign Minister, Marty Natalegawa at Gedung Pancasila, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. -

The League of Thirteen Media Concentration in Indonesia

THE LEAGUE OF THIRTEEN MEDIA CONCENTRATION IN INDONESIA author: MERLYNA LIM published jointly by: PARTICIPATORY MEDIA LAB AT ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY & 2012 The league of thirteen: Media concentration in Indonesia Published jointly in 2012 by Participatory Media LaB Arizona State University Tempe, Arizona United States & The Ford Foundation This report is Based on the research funded By the Ford Foundation Indonesia Office. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons AttriBution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License How to cite this report: Lim, M. 2012. The League of Thirteen: Media Concentration in Indonesia. Research report. Tempe, AZ: Participatory Media LaB at Arizona State University. AvailaBle online at: http://www.puBlic.asu.edu/~mlim4/files/Lim_IndoMediaOwnership_2012.pdf. THE LEAGUE OF THIRTEEN: MEDIA CONCENTRATION IN INDONESIA By Merlyna Lim1 The demise of the Suharto era in 1998 produced several positive developments for media democratization in Indonesia. The Department of Information, once led By the infamous Minister Harmoko was aBandoned, followed By several major deregulations that changed the media landscape dramatically. From 1998 to 2002, over 1200 new print media, more than 900 new commercial radio and five new commercial television licenses were issued. Over the years, however, Indonesian media went ‘Back to Business’ again. Corporate interests took over and continues to dominate the current Indonesian media landscape. MEDIA OWNERSHIP From Figure 1 we can see that the media landscape in Indonesia is dominated By only 13 groups: the state (with public status) and 12 other commercial entities. There are 12 media groups (see Table 1) have control over 100% of national commercial television shares (10 out of 10 stations).