Parental Expectations and Young People's Migratory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Captures Asean

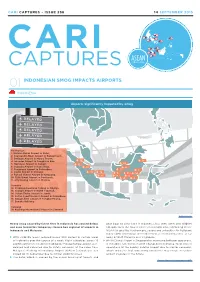

CARI CAPTURES • ISSUE 236 14 SEPTEMBER 2015 CARI ASEAN CAPTURES REGIONAL 01 INDONESIAN SMOG IMPACTS AIRPORTS INDONESIA Airports Significantly Impacted by Smog DELAYED DELAYED DELAYED DELAYED DELAYED Kalimantan 1. Melalan Melak Airport in Kutai, 2. Syansyudin Noor Airport in Banjarmasin, 3. Beringin Airport in Muara Teweh, 4. Iskandar Airport in Pangkalan Bun 13 11 5. Haji Asan Airport in Sampit, 12 18 6. Supadio Airport in Kubu Raya, 14 8 7. Pangsuma Airport in Putussibau, 7 1 8. Susilo Airport in Sintang, 15 16 6 3 10 9. Rahadi Usman Airport in Ketapang, 17 9 5 10. Tjilik Riwut Airport in Pontianak, 4 2 11. Atty Besing Airport in Malinau. Sumatra 12. Ferdinand Lumban Tobing in Sibolga, 13. Silangit Airport in North Tapanuli, 14. Sultan Thaha Airport in Jambi, 15. Sultan Syarif Kasim II Airport in Pekanbaru, 16. Depati Amir Airport in Pangkal Pinang, 17. Bangka Belitung Sarawak 18. Kuching International Airport in Sarawak Antara News Heavy smog caused by forest fires in Indonesia has caused delays peat bogs to clear land in Indonesia, has seen some 400 wildfire and even forced the temporary closure two regional of airports in hotspots over the course of the past month alone according to the Indonesia and Malaysia. NOAA-18 satellite; furthermore, severe and unhealthy Air Pollutant Index (API) recordings were observed at several locations as far With visibility levels reduced below 800 meters in certain areas away as East Malaysia and Singapore of Indonesia over the course of a week, flight schedules across 16 Whilst Changi Airport in Singapore -

Laporan Kinerja Badan Geologi Tahun 2014

LAPORAN KINERJA BADAN GEOLOGI TAHUN 2014 BADAN GEOLOGI KEMENTERIAN ENERGI DAN SUMBER DAYA MINERAL Tim Penyusun: Oman Abdurahman - Priatna - Sofyan Suwardi (Ivan) - Rian Koswara - Nana Suwarna - Rusmanto - Bunyamin - Fera Damayanti - Gunawan - Riantini - Rima Dwijayanti - Wiguna - Budi Kurnia - Atep Kurnia - Willy Adibrata - Fatmah Ughi - Intan Indriasari - Ahmad Nugraha - Nukyferi - Nia Kurnia - M. Iqbal - Ivan Verdian - Dedy Hadiyat - Ari Astuti - Sri Kadarilah - Agus Sayekti - Wawan Bayu S - Irwana Yudianto - Ayi Wahyu P - Triyono - Wawan Irawan - Wuri Darmawati - Ceme - Titik Wulandari - Nungky Dwi Hapsari - Tri Swarno Hadi Diterbitkan Tahun 2015 Badan Geologi Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral Jl. Diponegoro No. 57 Bandung 40122 www.bgl.esdm.go.id Pengantar Geologi merupakan salah satu pendukung penting dalam program pembangunan nasional. Untuk program tersebut, geologi menyediakan informasi hulu di bidang En- ergi dan Sumber Daya Mineral (ESDM). Di samping itu, kegiatan bidang geologi juga menyediakan data dan informasi yang diperlukan oleh berbagai sektor, seperti mitigasi bencana gunung api, gerakan tanah, gempa bumi, dan tsunami; penataan ruang, pemba- ngunan infrastruktur, pengembangan wilayah, pengelolaan air tanah, dan penyediaan air bersih dari air tanah. Pada praktiknya, pembangunan kegeologian di tahun 2014 masih menghadapi beber- apa isu strategis berupa peningkatan kualitas hidup masyarakat Indonesia mencapai ke- hidupan yang sejahtera, aman, dan nyaman mencakup ketahanan energi, lingkungan dan perubahan iklim, bencana alam, tata ruang dan pengembangan wilayah, industri mineral, pengembangan informasi geologi, air dan lingkungan, pangan, dan batas wilayah NKRI (kawasan perbatasan dan pulau-pulau terluar). Ketahanan energi menjadi isu utama yang dihadapi sektor ESDM, sekaligus menjadi yang dihadapi oleh Badan Geologi yang mer- upakan salah satu pendukung utama bagi upaya-upaya sektor ESDM. -

6 Intersecting Spheres of Legality and Illegality | Considered Legitimate by Border Communities Back in Control of Their Traditional Forests

6 Intersecting spheres of legality and illegality For those living in the borderland, it is a zone unto itself, neither wholly subject to the laws of states nor completely independent of them. Their autonomous practices make border residents and their cross-border cul- tures a zone of suspicion and surveillance; the visibility of the military and border forces an index of official anxiety (Abraham 2006:4). Borderland lawlessness, or the ‘twilight zone’ between state law and au- thority, often provides fertile ground for activities deemed illicit by one or both states – smuggling, for example. Donnan and Wilson (1999) note how borders can be both ‘used’ (by trade) and ‘abused’ (by smuggling) concur with Van Schendel’s claim that ‘[t]he very existence of smuggling undermines the image of the state as a unitary organization enforcing law and order within clearly defined territory’ (1993:189). This is espe- cially true along the remote, rugged and porous borders of Southeast Asia where the smuggling of cross-border contraband has a deep-rooted history (Tagliacozzo 2001, 2002, 2005). As noted in Chapters 3, 4 and 5, illegal trade or smuggling (semukil) of various contraband items back and forth across the West Kalimantan- Sarawak border has been a continuous concern of Dutch and Indonesian central governments ever since the establishment of the border. Drawn by the peculiar economic and social geography, several scholars men- tion how borderlands often attract opportunistic entrepreneurs. They also mention how such border zones may promote the growth of local leadership built on illegal activities and maintained through patronage, violence and collusion.1 Alfred McCoy asserts that the presence of such local leadership at the edges of Southeast Asian states is a significant 1 Gallant 1999; McCoy 1999; Van Schendel 2005; Sturgeon 2005; Walker 1999. -

Traditional Knowledge, Perceptions and Forest Conditions in a Dayak Mentebah Community, West Kalimantan, Indonesia

WORKING PAPER Traditional knowledge, perceptions and forest conditions in a Dayak Mentebah community, West Kalimantan, Indonesia Edith Weihreter Working Paper 146 Traditional knowledge, perceptions and forest conditions in a Dayak Mentebah community, West Kalimantan, Indonesia Edith Weihreter Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) Working Paper 146 © 2014 Center for International Forestry Research Content in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0), http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Weihreter E. 2014. Traditional knowledge, perceptions and forest conditions in a Dayak Mentebah community, West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Working Paper 146. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR. Photo by Edith Weihreter/CIFOR Nanga Dua Village on Penungun River with canoes and a gold digging boat CIFOR Jl. CIFOR, Situ Gede Bogor Barat 16115 Indonesia T +62 (251) 8622-622 F +62 (251) 8622-100 E [email protected] cifor.org We would like to thank all donors who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Fund. For a list of Fund donors please see: https://www.cgiarfund.org/FundDonors Any views expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of CIFOR, the editors, the authors’ institutions, the financial sponsors or the reviewers. You have your way. I have my way. As for the right way, the correct way, and the only way, it does not exist. FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE Table of content List of abbreviations vi Acknowledgments vii 1 Introduction -

Kata Pengantar

This first edition published in 2007 by Tourism Working Group Kapuas Hulu District COPYRIGHT © 2007 TOURISM WORKING GROUP KAPUAS HULU DISTRICT All Rights Reserved, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted to any form or by any means, electronic, mecanical, photo-copying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright owners. CO-PUBLISHING MANAGER : Hermayani Putera, Darmawan Isnaini HEAD OF PRODUCTION : Jimmy WRITER : Anas Nasrullah PICTURES TITLE : Jean-Philippe Denruyter ILUSTRATOR : Sugeng Hendratno EDITOR : Syamsuni Arman, Caroline Kugel LAYOUT AND DESIGN : Jimmy TEAM OF RESEARCHER : Hermas Rintik Maring, Anas Nasrullah, Rudi Zapariza, Jimmy, Ade Kasiani, Sugeng Hendratno. PHOTOGRAPHIC CREDITS Sugeng Hendratno: 1, 2BL, 2BR, 4B, 5L, 6, 7, 14A, 14BR, 21R, 21BL, 22B, 26L, 27T, 27A, 30, 33, 35, 40AL, 40AR, 43A, 43BR, 46T, 51, 54BL, 55B, 58BL, 58BR, 64BR, 66A, 67A, 68, 72B, 75A, 76L, 77BL, 77BR, 78, 79BL, 80L, 83B, 84B, 85B, 90B, 94L, 94B, 94A, 99L, 102BL, 103M1, 103M3, 103M5, 103R3, 103R6, 104L1, 104M2, 105L3, 105L4, 105M3, 105R1, 105R3, 105R4, Jimmy: 2A, 3A, 3L, 4T, 5B, 13L, 14R, 14BL, 15, 16 AL, 16 AR, 16B, 17A, 18T, 18R, 18BL, 18BR, 19, 20, 21T, 21BR, 22T, 22A, 23AL, 24, 25, 32BL, 32BR, 40T, 40L, 42, 43BL, 44 All, 45 All, 47, 48, 49, 50 All, 52, 53L, 54BR, 55T, 57TR, 57B, 59 All, 61AL, 62, 64BL, 66R, 69A, 69BL, 69BR, 70 All, 71AL, 71AR, 71BL, 71BR, 72A, 74, 75B, 76B, 79A, 79BR, 80B, 81, 83, 84L, 85AL, 85AR, 87 All, 88, 89, 90AL, 90AR, 90M, 92, 93 All, 98B, 99B, -

Cross-Border Correlation of Geological Formations in Sarawak and Kalimantan

Geol. Soc. Malaysia, Bulletin 28, November 1991; pp. 63 - 95 Cross-border correlation of geological formations in Sarawak and Kalimantan ROBERT B. TATE Dept. of Geology University of Malaya 59100 Kuala Lumpur. Abstract: Recent geological mapping by an AustralianlIndonesian team in West and Central Kalimantan has resulted in a revised stratigraphy for the Paleozoic-Tertiary igneous and sedimentary successions in terms of (1) Continental Basement and Platform (ShelO Sedimentary rocks, (2) Continental Arc intrusives and volcanics, (3) Oceanic Basement and overlying sedimentary rocks and (4) Foreland Rocks (Post-tectonic igneous rocks and sedimentary basins, (5) Tectonic melange and (6) Surficial deposits. Correlation charts are presented to reconcile the stratigraphy across the international border between Sarawak, East Malaysia, and Kalimantan, Indonesia. INTRODUCTION The stratigraphy of Central and West Kalimantan has been described recently by Pieters et al. (1987), Pieters & Supriatna (1989a) and Williams et al. (1988), and for West Sarawak by Tan (1986). All authors have correlated certain individual stratigraphic formations, particularly where they are common to both Sarawak and Kalimantan but no detailed cross-border correlation has been presented to date. This paper attempts to provide a regional correlation between Central and Northwest Kalimantan and South and West Sarawak (Table 1) and, as a result of the new data, to indicate fundamental changes to the interpretation of the geology of this part of Borneo. The completed Indonesian-Australian Geological Mapping Project (IAGMP) covers an area of some 850 km long and 250-300 km wide in Central and West Kalimantan (Pieters & Supriatna, 1989b); twelve preliminary geological maps at 1: 250,000 scale (see key to Fig.l) and a 1:1 million compilation map are published and one 1:250,000 map is in preparation. -

00-Program-And-Abstracs-EACEF5

2 CONTENT Welcome Message Conference Chairman ·····················································4 Welcome Message Founding Chairman of EACEF ··········································5 COMMITTEES ································································································6 GENERAL INFORMATION ···············································································8 VENUE INFORMATIONS ··············································································· 10 PROGRAM AT A GLANCE ············································································· 13 KEYNOTE SPEAKERS····················································································· 15 INVITED SPEAKERS ······················································································ 19 KEYNOTE AND INVITED SPEECHES ······························································· 21 PARALLEL SESSIONS····················································································· 23 INSTRUCTION FOR SPEAKERS ······································································ 39 SOCIAL PROGRAM ······················································································· 40 INFORMATION ABOUT SURABAYA ······························································ 49 ABSTRACTS ·································································································· 51 Construction Project and Safety Management ····································· 51 Environmental Engineering ·································································· -

Parental Expectations and Young People's Migratory

Jurnal Psikologi Volume 44, Nomor 1, 2017: 66 - 79 DOI: 10.22146/jpsi.26898 /®π¨®≥1$¡∑¨™ª®1®µ18∂º1/¨∂∑≥¨1,∞Æπ®¢1 Experiences in Indonesia Wenty Marina Minza1 Center for Indigenous and Cultural Psychology Faculty of Psychology Universitas Gadjah Mada Abstract. Based on a one year qualitative study, this paper examines the migratory aspirations and experiences of non-Chinese young people in Pontianak, West Kalimantan, Indonesia. It is based on two main questions of migration i1¨1™∂¨¡11¿∂º1¨≥¨1 education to work transition: 1) How do young people in provincial cities perceive processes of migration? 2) What is the role of intergenerational relations in realizing these aspirations? This paper will describe the various strategies young people employ to realize their dreams of obtaining education in Java, the decisions made by those who fail to do so, and the choices made by migrants after finishing their education in Java. It will contribute to a body of knowledge on ¢º1¨∂≥¨1¨´º™®ª∞11 ≤1®µ1®µ1 how inter-generational dynamics play out in that process. Keywords: intergenerational relation, migratory aspiration, youth Internal1 migration plays a key role in Java. Both the younger and older gene- mapping mobility patterns among young ration in Pontianak generally associate people, as many young people continue to Java with ideas of progress, opportunities migrate within their home country (Argent for social mobility, and the success of & Walmsley, 2008). Indonesia is no excep- inter-generational reproduction or regene- tion. The highest participation of rural ration. Yet, migration involves various urban migration in Indonesia is among negotiation processes that go beyond an young people under the age of 29, mostly analysis of push and pull factors. -

Borneo West to East Crossing Adventure

Borneo West to East Crossing Adventure Borneo • West to East Crossing Adventure Jakarta – Pontianak – Putussibau – Kapuas River – Bungan River – Tanjung Lokang – Sei Bulit – Bungan River – Piang Lo’ong – Muller • Range – Muara Kuting – Saite – Ting Ohang – Long Bagun – Samarinda - Balikpapan Cross one of the most rugged islands on earth from Tour Style Adventure Trekking West to East using roads, rivers and feet Tour Start Jakarta Traversing the jungle Tour End Balikpapan Experience amazing rivers – Kapuas and Bungan Accommodation Hotels, Camping Rivers Included Meals 16 Breakfasts, 15 lunches, Sleep in a houseboat! 14 Dinners Difficulty Level Very Difficult The Cross Borneo West to East adventure is a real once in a lifetime adventure. Those who have undertaken this trip in the past have describe it as the most challenging and the most enjoyable trekking trip they had ever done. The ultimate challenge - crossing one of the most rugged islands on earth from West to East using roads, rivers and feet, we traverse the jungle of Kalimantan in Indonesian Borneo. To enjoy this trip, you need to be prepared to accept whatever the jungles and rivers serve up! A good fitness level, a strong sense of determination and a flexible attitude are essential. Bor06 Pioneer Expeditions ● 4 Minster Chambers● 43 High Street● Wimborne ● Dorset ● BH21 1HR t 01202 798922 ● e [email protected] We really are one of the few specialists that really “do” off the beaten track and unique adventures in BORNEO. We are driven by a passion for adventure travel and wildlife and Borneo is one of our main specialities. We know it inside- out, and continuously collaborate with our local partners and tour guides to ensure that you have the best experiences on your dream Borneo adventure – this focus is reflected in our uniquely wonderful itineraries. -

Borneo-5-Preview.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Borneo Brunei Darussalam Sabah p208 p50 Sarawak p130 Kalimantan p228 Paul Harding, Brett Atkinson, Anna Kaminski PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Borneo . 4 SABAH . 50 Sepilok . 90 Borneo Map . 6 Kota Kinabalu . 52 Sandakan Archipelago . 94 Deramakot Forest Borneo’s Top 17 . 8 Tunku Abdul Rahman National Park . 68 Reserve . 95 Need to Know . 16 Pulau Manukan . 68 Sungai Kinabatangan . 96 First Time Borneo . 18 Pulau Mamutik . 68 Lahad Datu . 101 Pulau Sapi . 69 Danum Valley What’s New . 20 Conservation Area . 103 Pulau Gaya . 69 Tabin Wildlife Reserve . 105 If You Like . 21 Pulau Sulug . 70 Semporna . 106 Month by Month . 23 Northwestern Sabah . 70 Semporna Itineraries . 26 Mt Kinabalu & Archipelago . 107 Kinabalu National Park . 70 Tawau . 114 Outdoor Adventures . 34 Northwest Coast . 79 Tawau Hills Park . 117 Diving Pulau Sipadan . 43 Eastern Sabah . 84 Maliau Basin Sandakan . .. 84 Regions at a Glance . .. 47 Conservation Area . 118 BAMBANG WIJAYA /SHUTTERSTOCK © /SHUTTERSTOCK WIJAYA BAMBANG © NORMAN ONG/SHUTTERSTOCK LOKSADO P258 JAN KVITA/SHUTTERSTOCK © KVITA/SHUTTERSTOCK JAN ORANGUTAN, TANJUNG SARAWAK STATE PUTING NATIONAL PARK P244 ASSEMBLY P140 Contents UNDERSTAND Southwestern Sabah . 120 Tutong & Borneo Today . 282 Belait Districts . 222 Interior Sabah . 120 History . 284 Beaufort Division . 123 Tutong . 222 Pulau Tiga Jalan Labi . 222 Peoples & Cultures . 289 National Park . 125 Seria . 223 The Cuisines Pulau Labuan . 126 Temburong of Borneo . 297 District . 223 Natural World . 303 Bangar . 224 SARAWAK . 130 Batang Duri . 225 Kuching . 131 Ulu Temburong Western Sarawak . 151 National Park . 225 SURVIVAL Bako National Park . 152 GUIDE Santubong Peninsula . 155 KALIMANTAN . 228 Semenggoh Responsible Travel . -

Highlands Eco Challenge

CHINA Highlands WORKING TOGETHER TO SAVE MYANMAR THE HEART in The Heart OF BORNEO INDIA THAILAND HIGHLANDS ECO of Borneo © WWF-MALAYSIA CHALLENGE III © WWF-MALAYSIA 27 June - 10 July 2019 INDONESIA he Heart of Borneo Highlands Eco The event is limited to 50 participants Highlands TChallenge III that will be held from only and each stage of the Eco Chal- of Heart 27th June – 10th July 2019 is organised by lenges comes with activities that bring of Borneo the Alliance of the Indigenous People of participants through the footsteps of the the Highlands of Borneo (FORMADAT). ancestors of the Highland peoples and an This is an ecotourism adventure that re- appreciation of the wonders of the natural lives history, culture and stewardship environment. So the concept of treading of nature. lightly, “take nothing but photographs, leave nothing but footprints”, is core to the organisers and participants. © WWF-MALAYSIA The idea to form a community forum was initiated in the year 2003 by late YB Dato’ Judson Sakai Tagal, Assistant Minis- year 2011, FORMADAT has been officially means of community-based ecotourism, ter of Infrastructure Development and registered in Sarawak and Sabah, Malay- organic farming and agro-forestry, com- © WWF-MALAYSIA / JAYL LANGUB Communication, Sarawak. The inspira- WWF - HEART OF BORNEO sia; and Krayan, Indonesia. munication and information technology, tion had encouraged community of the and the preservation of cultural and natu- Highlands of Borneo to come together The highlands include the sub-districts FLAGSHIP PACKAGE ECO - TOURISM ral heritage of the Highlands to benefit and established FORMADAT in Long of Krayan and South Krayan in North present and future generation. -

Gawaidayak: Efforts to Preserve the Tradition of the Kantuk Triberanyai Village, West Kalimantan Indonesia

Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education Vol.12 No.14 (2021), 2478– 2485 Research Article GawaiDayak: Efforts to Preserve The Tradition of The Kantuk TribeRanyai Village, West Kalimantan Indonesia SigitWidiyartoa, DadangSunendarb, Iskandarwassidc, Sumiyadi d aThe Lecturer at University of Indraprasta PGRI Jakarta Indonesia, bThe Postgraduate Professor atIndonesia University of Education Bandung Indonesia, c The Postgraduate ProfessorIndonesia University of Education Bandung Indonesia, d Doctor,Indonesia University of Education Bandung Indonesia Article History: Do not touch during review process(xxxx) _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract: The purpose of this study was to describe what and how the GawaiDayak oral tradition was carried out in Ranyai Village, West Kalimantan, and to describe the supporting factors and efforts to preserve the GawaiDayak tradition in Ranyai Village, West Kalimantan. Qualitative research is carried out in order to be able to explain and analyze phenomena, events, social phenomena, group beliefs, and opinions of a person or society towards something. Data were collected through interviews, documentation and document analysis. The method of data analysis was the stages of data collection, data reduction, data display and conclusion drawing. The research results were that the GawaiDayak tradition was a tradition that contains divine values. The GawaiDayak tradition presents the KantukDayak tribe as human beings who are good at being grateful. The supporting factors of the GawaiDayak tradition could help the DayakGawai tradition continue to develop and be sustainable Keywords: GawaiDayak, Tradition, Kantuk Tribe, West Kalimantan ___________________________________________________________________________ Introduction Cultural preservation in Indonesia is an effort to maintain the values of local wisdom that are spread throughout Indonesia. These efforts need good cooperation and communication between the government and the community.