Poisons and Antidotes Among the Taman of West Kalimantan, Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Megalith.Pdf

PUBLICATIONS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER ETHNOLOGICAL SERIES No. Ill THE MEGALITHIC CULTURE OF INDONESIA Published by the University of Manchester at THE UNIVERSITY PRESS (H. M. MCKECHNIE, Secretary) 12 LIME GROVE, OXFORD ROAD, MANCHESTER LONGMANS, GREEN & CO. LONDON : 39 Paternoster Row : . NEW YORK 443-449 Fourth Avenue and Thirtieth Street CHICAGO : Prairie Avenue and Twenty-fifth Street BOMBAY : Hornby Road CALCUTTA: G Old Court House Street MADRAS: 167 Mount Road THE MEGALITHIC CULTURE OF INDONESIA BY , W. J. PERRY, B.A. MANCHESTEE : AT THE UNIVERSITY PBESS 12 LIME GROVE, OXFOBD ROAD LONGMANS, GREEN & CO. London, New York, Bombay, etc. 1918 PUBLICATIONS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER No. CXVIII All rights reserved TO W. H. R. RIVERS A TOKEN OF AFFECTION AND REGARD PREFACE. IN 1911 the stream of ethnological research was directed by Dr. Rivers into new channels. In his Presidential Address to the Anthropological Section of the British Association at Portsmouth he expounded some of the effects of the contact of diverse cul- tures in Oceania in producing new, and modifying pre-existent institutions, and thereby opened up novel and hitherto unknown fields of research, and brought into prominence once again those investigations into movements of culture which had so long been neglected. A student who wishes to study problems of culture mixture and transmission is faced with a variety of choice of themes and of regions to investigate. He can set out to examine topics of greater or less scope in circumscribed areas, or he can under- take world-wide investigations which embrace peoples of all ages and civilisations. -

Spatial Poesis and Localized Identity in Buli

Chapter 8. Speaking of Places: Spatial poesis and localized identity in Buli Nils Bubandt Introduction This paper seeks to explore the nexus between language, space and identity.1 It does so by focusing on the frequent use of orientational or deictic words in Buli language and relating it to the processes of identification. Spatial deixis seems to be relevant to the processes of identification at two levels: those of individual subjectivity on the one hand and those of cultural identity and differentiation on the other. In this discussion of the relationship between the perception of space and forms of identification I hope to suggest a possible connection between the numerous descriptive analyses of orientational systems in eastern Indonesia (Adelaar 1997; Barnes 1974, 1986, 1988, 1993; Taylor 1984; Teljeur 1983; Shelden 1991; Yoshida 1980), the discussion of subjectivity and the role of deixis in phenomenological linguistic theory (Benveniste 1966; Bühler 1982; Lyons 1982; Fillmore 1982), and broader debates on the spatial processes operative in cultural identification. The basic argument is that the same linguistic conventions for spatial orientation in Buli function to posit both individual subjectivity and cultural identity. At the former level, spatial deixis establishes the speaker as a ªlocativeº subject with a defined but relative position in the world. The subject necessarily occupies a place in space and, in most acts of speaking, posits this.2 I shall argue that subjectivity in Buli is posited continually in speech through spatial deixis. At the broader level of cultural identification, however, space is laid out in absolute terms. Here, space terminates in certain culturally significant ªheterotopiasº (Foucault 1986), that is, places of important symbolic difference to Buli. -

Rules and Options

Rules and Options The author has attempted to draw as much as possible from the guidelines provided in the 5th edition Players Handbooks and Dungeon Master's Guide. Statistics for weapons listed in the Dungeon Master's Guide were used to develop the damage scales used in this book. Interestingly, these scales correspond fairly well with the values listed in the d20 Modern books. Game masters should feel free to modify any of the statistics or optional rules in this book as necessary. It is important to remember that Dungeons and Dragons abstracts combat to a degree, and does so more than many other game systems, in the name of playability. For this reason, the subtle differences that exist between many firearms will often drop below what might be called a "horizon of granularity." In D&D, for example, two pistols that real world shooters could spend hours discussing, debating how a few extra ounces of weight or different barrel lengths might affect accuracy, or how different kinds of ammunition (soft-nosed, armor-piercing, etc.) might affect damage, may be, in game terms, almost identical. This is neither good nor bad; it is just the way Dungeons and Dragons handles such things. Who can use firearms? Firearms are assumed to be martial ranged weapons. Characters from worlds where firearms are common and who can use martial ranged weapons will be proficient in them. Anyone else will have to train to gain proficiency— the specifics are left to individual game masters. Optionally, the game master may also allow characters with individual weapon proficiencies to trade one proficiency for an equivalent one at the time of character creation (e.g., monks can trade shortswords for one specific martial melee weapon like a war scythe, rogues can trade hand crossbows for one kind of firearm like a Glock 17 pistol, etc.). -

Are Cabbage Trees Worth Anything? Relating Ecological and Human Values in the Cabbage Tree, Fl Kouka

Are cabbage trees worth anything? Relating ecological and human values in the cabbage tree, fl kouka PHILIP SIMPSON piles, and fence posts. The cabbage tree exemplifies the relationship be Cabbage trees entered 'New Zealand' along tropical tween people and plants, not only the whole.tree itself archipelagos some 15 million years ago.' They have but also its parts, the leaves, the internal tissues, and adapted to the vicissitudes of sea-level, mountain build their biochemistry. ing and erosion, and climate change, and have evolved When Polynesian settlers named the New Zealand into different species and regional forms. A remarkable cabbage trees 'ti' they were retaining a tradition of set of structural and physiological features has devel using its tropical relative, Cordyline fruticosa (formerly oped to equip them for survival in a changeable and known as C. terminalis). They brought it with them and sometimes extreme environment. called it tl pore, 'the 'short' cabbage tree. European It was the qualities of strength and durability that whalers and sealers adopted 'cabbage palm' from Cook's were seized on by Maori, and they favoured some or first voyage because the tips of palms were often eaten selected new forms to satisfy their daily needs. The as a vegetable ('cabbage') by sailors, and because of the same qualities of survival underscore Pakeha respect archetypal similarity between cabbage trees and tropi for cabbage trees. They too have recognised variety and cal palms that the temperate travellers had seen for the have bred new forms to satisfy their aesthetic mores. A first time. It is perhaps the leafy, tropical look com sense of national identity has grown around the cab bined with temperate strength that account for the world bage tree and people have been shocked by the epi fame of cabbage trees. -

Parental Expectations and Young People's Migratory

Jurnal Psikologi Volume 44, Nomor 1, 2017: 66 - 79 DOI: 10.22146/jpsi.26898 Parental Expectations and Young People’s Migratory Experiences in Indonesia Wenty Marina Minza1 Center for Indigenous and Cultural Psychology Faculty of Psychology Universitas Gadjah Mada Abstract. Based on a one-year qualitative study, this paper examines the migratory aspirations and experiences of non-Chinese young people in Pontianak, West Kalimantan, Indonesia. It is based on two main questions of migration in the context of young people’s education to work transition: 1) How do young people in provincial cities perceive processes of migration? 2) What is the role of intergenerational relations in realizing these aspirations? This paper will describe the various strategies young people employ to realize their dreams of obtaining education in Java, the decisions made by those who fail to do so, and the choices made by migrants after the completion of their education in Java. It will contribute to a body of knowledge on young people’s education to work transitions and how inter-generational dynamics play out in that process. Keywords: intergenerational relation; migratory aspiration; youth Internal1 migration plays a key role in older generation in Pontianak generally mapping mobility patterns among young associate Java with ideas of progress, people, as many young people continue to opportunities for social mobility, and the migrate within their home country (Argent success of inter-generational reproduction & Walmsley, 2008). Indonesia is no excep- or regeneration. Yet, migration involves tion. The highest participation of rural various negotiation processes that go urban migration in Indonesia is among beyond an analysis of push and pull young people under the age of 29, mostly factors. -

A Dictionary of Kashmiri Proverbs & Sayings

^>\--\>\-«s-«^>yss3ss-s«>ss \sl \ I'!- /^ I \ \ "I I \ CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Library PN 6409.K2K73 A dictionary of Kashmiri proverbs & sayi 3 1924 023 043 809 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924023043809 — : DICTIONARY KASHMIRI PROVERBS & SAYINGS Explained and Illustrated from the rich and interesting Folklore of the Valley. Rev. J. HINTON KNOWLES, F.R.G.S., M.R.A.S., &c., (C. M. S.) MISSIONARY TO THE KASHMIRIS. A wise man will endeavour " to understand a proverb and the interpretation." Prov. I. vv. 5, 6. BOMBAY Education Society's Press. CALCUTTA :—Thackbb, Spink & Co. LONDON :—Tetjenee & Co. 1885. \_All rights reserved.'] PREFACE. That moment when an author dots the last period to his manuscript, and then rises up from the study-chair to shake its many and bulky pages together is almost as exciting an occasion as -when he takes a quire or so of foolscap and sits down to write the first line of it. Many and mingled feelings pervade his mind, and hope and fear vie with one another and alternately overcome one another, until at length the author finds some slight relief for his feelings and a kind of excuse for his book, by writing a preface, in which he states briefly the nature and character of the work, and begs the pardon of the reader for his presumption in undertaking it. A winter in Kashmir must be experienced to be realised. -

SEED of the MONTH: Ti Plant

SEED OF THE MONTH: Ti plant Common Name: Ti or Ki in Hawaiian Scientific Name: Cordyline fruticosa Family: Asparagaceae Genus: Dracaena Height: Spacing: Sun Exposure: Up to 13ft 3-4 ft full sun to moderate shade Details: Ti is an upright evergreen shrub with slender single or branched stems. Ti can add exciting color to a landscape with a tropical theme. Its color variations range red leaves to green and variegated. It is used in landscaping as an accent hedge, foundation or background planting. In container or above ground planter, ti is suitable for growing outdoors and indoors. Soil Requirements: acidic, well drained. Water Requirements: Water one to two times per week in-ground. If it’s planted in a container water a little more frequently. (Plants in containers tend to dry out more quickly than their counter-parts in-ground). Propagation Methods: Propagate from stem sections in pieces at least one inch long. One inch cuttings can lay vertically or horizontally into a rooting medium (perlite, vermiculite, or peat moss-sand mixture) so that three-fourths of the length is buried or ¼ inch of the diameter of the horizontal section is covered. Horizontal cuttings may grow in to several plants. Keep cuttings moist and partially shaded, mist 2-3 times per day. Rooting time is 2-4 weeks. Cuttings in plain water should be at least six inches long and the end of the cutting should be immersed in about 1 inch of water. Water in the container should be changed out occasionally. After a strong root system has developed, transplant the cuttings before the roots get too long and may break off in the planting process. -

Nature and Society: Anthropological Perspectives

Nature and Society Nature and Society looks critically at the nature/society dichotomy—one of the central dogmas of western scholarship— and its place in human ecology and social theory. Rethinking the dualism means rethinking ecological anthropology and its notion of the relation between person and environment. The deeply entrenched biological and anthropological traditions which insist upon separating the two are challenged on both empirical and theoretical grounds. By focusing on a variety of perspectives, the contributors draw upon developments in social theory, biology, ethnobiology and sociology of science. They present an array of ethnographic case studies—from Amazonia, the Solomon Islands, Malaysia, the Moluccan Islands, rural communities in Japan and north-west Europe, urban Greece and laboratories of molecular biology and high-energy physics. The key focus of Nature and Society is the issue of the environment and its relations to humans. By inviting concern for sustainability, ethics, indigenous knowledge and the social context of science, this book will appeal to students of anthropology, human ecology and sociology. Philippe Descola is Directeur d’Etudes, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris, and member of the Laboratoire d’Anthropologie Sociale at the Collège de France. Gísli Pálsson is Professor of Anthropology at the University of Iceland, Reykjavik, and (formerly) Research Fellow at the Swedish Collegium for Advanced Study in the Social Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden. European Association of Social Anthropologists The European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA) was inaugurated in January 1989, in response to a widely felt need for a professional association which would represent social anthropologists in Europe and foster co-operation and interchange in teaching and research. -

Differentiation and Distribution of Cordyline Viruses 1–4 in Hawaiian Ti Plants (Cordyline Fruticosa L.)

Viruses 2013, 5, 1655-1663; doi:10.3390/v5071655 OPEN ACCESS viruses ISSN 1999-4915 www.mdpi.com/journal/viruses Article Differentiation and Distribution of Cordyline Viruses 1–4 in Hawaiian ti Plants (Cordyline fruticosa L.) Michael Melzer 1,*, Caleb Ayin 1, Jari Sugano 2, Janice Uchida 1, Michael Kawate 1, Wayne Borth 1 and John Hu 1 1 Department of Plant and Environmental Protection Sciences, University of Hawaii, 3190 Maile Way, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (C.A); [email protected] (J.U.); [email protected] (M.K.); [email protected] (W.B.); [email protected] (J.H.) 2 Department of Plant and Environmental Protection Sciences, University of Hawaii, 45-260 Waikalua Road, Kaneohe, HI 96744, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-808-956-7887; Fax: +1-808-956-2832. Received: 3 May 2013; in revised form: 15 June 2013 / Accepted: 26 June 2013 / Published: 5 July 2013 Abstract: Common green ti plants (Cordyline fruticosa L.) in Hawaii can be infected by four recently characterized closteroviruses that are tentative members of the proposed genus Velarivirus. In this study, a reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay developed to detect and distinguish Cordyline virus 1 (CoV-1), CoV-2, CoV-3, and CoV-4 was used to determine: (i) the distribution of these viruses in Hawaii; and (ii) if they are involved in the etiology of ti ringspot disease. One hundred and thirty-seven common green ti plants with and without ti ringspot symptoms were sampled from 43 sites on five of the Hawaiian Islands and underwent the RT-PCR assay. -

Captures Asean

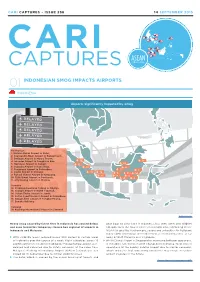

CARI CAPTURES • ISSUE 236 14 SEPTEMBER 2015 CARI ASEAN CAPTURES REGIONAL 01 INDONESIAN SMOG IMPACTS AIRPORTS INDONESIA Airports Significantly Impacted by Smog DELAYED DELAYED DELAYED DELAYED DELAYED Kalimantan 1. Melalan Melak Airport in Kutai, 2. Syansyudin Noor Airport in Banjarmasin, 3. Beringin Airport in Muara Teweh, 4. Iskandar Airport in Pangkalan Bun 13 11 5. Haji Asan Airport in Sampit, 12 18 6. Supadio Airport in Kubu Raya, 14 8 7. Pangsuma Airport in Putussibau, 7 1 8. Susilo Airport in Sintang, 15 16 6 3 10 9. Rahadi Usman Airport in Ketapang, 17 9 5 10. Tjilik Riwut Airport in Pontianak, 4 2 11. Atty Besing Airport in Malinau. Sumatra 12. Ferdinand Lumban Tobing in Sibolga, 13. Silangit Airport in North Tapanuli, 14. Sultan Thaha Airport in Jambi, 15. Sultan Syarif Kasim II Airport in Pekanbaru, 16. Depati Amir Airport in Pangkal Pinang, 17. Bangka Belitung Sarawak 18. Kuching International Airport in Sarawak Antara News Heavy smog caused by forest fires in Indonesia has caused delays peat bogs to clear land in Indonesia, has seen some 400 wildfire and even forced the temporary closure two regional of airports in hotspots over the course of the past month alone according to the Indonesia and Malaysia. NOAA-18 satellite; furthermore, severe and unhealthy Air Pollutant Index (API) recordings were observed at several locations as far With visibility levels reduced below 800 meters in certain areas away as East Malaysia and Singapore of Indonesia over the course of a week, flight schedules across 16 Whilst Changi Airport in Singapore -

Laporan Kinerja Badan Geologi Tahun 2014

LAPORAN KINERJA BADAN GEOLOGI TAHUN 2014 BADAN GEOLOGI KEMENTERIAN ENERGI DAN SUMBER DAYA MINERAL Tim Penyusun: Oman Abdurahman - Priatna - Sofyan Suwardi (Ivan) - Rian Koswara - Nana Suwarna - Rusmanto - Bunyamin - Fera Damayanti - Gunawan - Riantini - Rima Dwijayanti - Wiguna - Budi Kurnia - Atep Kurnia - Willy Adibrata - Fatmah Ughi - Intan Indriasari - Ahmad Nugraha - Nukyferi - Nia Kurnia - M. Iqbal - Ivan Verdian - Dedy Hadiyat - Ari Astuti - Sri Kadarilah - Agus Sayekti - Wawan Bayu S - Irwana Yudianto - Ayi Wahyu P - Triyono - Wawan Irawan - Wuri Darmawati - Ceme - Titik Wulandari - Nungky Dwi Hapsari - Tri Swarno Hadi Diterbitkan Tahun 2015 Badan Geologi Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral Jl. Diponegoro No. 57 Bandung 40122 www.bgl.esdm.go.id Pengantar Geologi merupakan salah satu pendukung penting dalam program pembangunan nasional. Untuk program tersebut, geologi menyediakan informasi hulu di bidang En- ergi dan Sumber Daya Mineral (ESDM). Di samping itu, kegiatan bidang geologi juga menyediakan data dan informasi yang diperlukan oleh berbagai sektor, seperti mitigasi bencana gunung api, gerakan tanah, gempa bumi, dan tsunami; penataan ruang, pemba- ngunan infrastruktur, pengembangan wilayah, pengelolaan air tanah, dan penyediaan air bersih dari air tanah. Pada praktiknya, pembangunan kegeologian di tahun 2014 masih menghadapi beber- apa isu strategis berupa peningkatan kualitas hidup masyarakat Indonesia mencapai ke- hidupan yang sejahtera, aman, dan nyaman mencakup ketahanan energi, lingkungan dan perubahan iklim, bencana alam, tata ruang dan pengembangan wilayah, industri mineral, pengembangan informasi geologi, air dan lingkungan, pangan, dan batas wilayah NKRI (kawasan perbatasan dan pulau-pulau terluar). Ketahanan energi menjadi isu utama yang dihadapi sektor ESDM, sekaligus menjadi yang dihadapi oleh Badan Geologi yang mer- upakan salah satu pendukung utama bagi upaya-upaya sektor ESDM. -

6 Intersecting Spheres of Legality and Illegality | Considered Legitimate by Border Communities Back in Control of Their Traditional Forests

6 Intersecting spheres of legality and illegality For those living in the borderland, it is a zone unto itself, neither wholly subject to the laws of states nor completely independent of them. Their autonomous practices make border residents and their cross-border cul- tures a zone of suspicion and surveillance; the visibility of the military and border forces an index of official anxiety (Abraham 2006:4). Borderland lawlessness, or the ‘twilight zone’ between state law and au- thority, often provides fertile ground for activities deemed illicit by one or both states – smuggling, for example. Donnan and Wilson (1999) note how borders can be both ‘used’ (by trade) and ‘abused’ (by smuggling) concur with Van Schendel’s claim that ‘[t]he very existence of smuggling undermines the image of the state as a unitary organization enforcing law and order within clearly defined territory’ (1993:189). This is espe- cially true along the remote, rugged and porous borders of Southeast Asia where the smuggling of cross-border contraband has a deep-rooted history (Tagliacozzo 2001, 2002, 2005). As noted in Chapters 3, 4 and 5, illegal trade or smuggling (semukil) of various contraband items back and forth across the West Kalimantan- Sarawak border has been a continuous concern of Dutch and Indonesian central governments ever since the establishment of the border. Drawn by the peculiar economic and social geography, several scholars men- tion how borderlands often attract opportunistic entrepreneurs. They also mention how such border zones may promote the growth of local leadership built on illegal activities and maintained through patronage, violence and collusion.1 Alfred McCoy asserts that the presence of such local leadership at the edges of Southeast Asian states is a significant 1 Gallant 1999; McCoy 1999; Van Schendel 2005; Sturgeon 2005; Walker 1999.