Department of Architecture Architectural Design Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FOOTBALL QATARI COLTS Bow

P 11 | FOOTBALL P 28 | BASKETBALL QATARI COLTS bOW OUT QATAR RARING TO GO Qatar suffer a shock defeat at the hands of Tajikistan Qatar look to make an impression at the FIBA in their crucial qualifier to bow out of reckoning Asia Championship in China even though for the Asian Under-16 Championship finals. things are unlikely to be easy for them. WEDNESDAY, SEPTEmbER 23, 2015 | Vol X | No.34 | QR 2.00 www.dohastadiumplusqatar.com Follow us on LUCK &Lekhwiya startTOIL their Qatar Stars League title defence with a laboured and somewhat lucky win over Qatar Sports Club. PAGES 6-10 DSP/Mohammed Dabboos DSP/Mohammed UK ...................................... £1 UAE ...............................Dh 5 Europe ............................. €2 Yemen..................75 Riyals P 16 | FOCUS ON ASPIRE P 20 | POSTER Oman ...............200 Baisas Sudan ...................1 Pound Bahrain ..................200 Fils KSA .......................... 2 Riyals Egypt .............................LE 2 Jordan ....................500 Fils Lebanon ..........3,000 Livre Iraq .................................... $1 Changing attitude FRANCESCO Kuwait ....................250 Fils Palestine ......................... $1 EXCLUSIVE Morocco ......................Dh 6 Syria .............................LS 20 INTERVIEW towards fitness TOTTI www.dohastadiumplusqatar.com www.dohastadiumplusqatar.com | WEDNESDAY, SEptEmbEr 23, 2015 3 EXCITEMENT NOW OPINION » The writer can be contacted at: JUST A TOUCH AWAY Editor-in-Chief Dr Ahmed Al Mohannadi [email protected] Managing Editor Kumar Ravi Senior Editor/Writer Aswin Abraham Senior Sports Writer N Ganesh Sports Writers Sajith B Warrier Aju George Chris Mohammad Amin-ul Islam Sarath Pookkat Being role model certainly not Photographers Mohan Vinod Divakaran Fadi Al Assaad Mohammed Dabboos a privilege everyone can have A K BijuRaj Graphic Designers Abhilash Chacko rOLE model is someone who can influence a And last week, they shook hands, somewhat Gopakumar K person’s life in a positive light. -

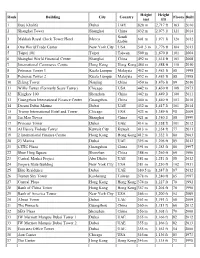

List of World's Tallest Buildings in the World

Height Height Rank Building City Country Floors Built (m) (ft) 1 Burj Khalifa Dubai UAE 828 m 2,717 ft 163 2010 2 Shanghai Tower Shanghai China 632 m 2,073 ft 121 2014 Saudi 3 Makkah Royal Clock Tower Hotel Mecca 601 m 1,971 ft 120 2012 Arabia 4 One World Trade Center New York City USA 541.3 m 1,776 ft 104 2013 5 Taipei 101 Taipei Taiwan 509 m 1,670 ft 101 2004 6 Shanghai World Financial Center Shanghai China 492 m 1,614 ft 101 2008 7 International Commerce Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 484 m 1,588 ft 118 2010 8 Petronas Tower 1 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 8 Petronas Tower 2 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 10 Zifeng Tower Nanjing China 450 m 1,476 ft 89 2010 11 Willis Tower (Formerly Sears Tower) Chicago USA 442 m 1,450 ft 108 1973 12 Kingkey 100 Shenzhen China 442 m 1,449 ft 100 2011 13 Guangzhou International Finance Center Guangzhou China 440 m 1,440 ft 103 2010 14 Dream Dubai Marina Dubai UAE 432 m 1,417 ft 101 2014 15 Trump International Hotel and Tower Chicago USA 423 m 1,389 ft 98 2009 16 Jin Mao Tower Shanghai China 421 m 1,380 ft 88 1999 17 Princess Tower Dubai UAE 414 m 1,358 ft 101 2012 18 Al Hamra Firdous Tower Kuwait City Kuwait 413 m 1,354 ft 77 2011 19 2 International Finance Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 412 m 1,352 ft 88 2003 20 23 Marina Dubai UAE 395 m 1,296 ft 89 2012 21 CITIC Plaza Guangzhou China 391 m 1,283 ft 80 1997 22 Shun Hing Square Shenzhen China 384 m 1,260 ft 69 1996 23 Central Market Project Abu Dhabi UAE 381 m 1,251 ft 88 2012 24 Empire State Building New York City USA 381 m 1,250 -

City Branding: Part 2: Observation Towers Worldwide Architectural Icons Make Cities Famous

City Branding: Part 2: Observation Towers Worldwide Architectural Icons Make Cities Famous What’s Your City’s Claim to Fame? By Jeff Coy, ISHC Paris was the world’s most-visited city in 2010 with 15.1 million international arrivals, according to the World Tourism Organization, followed by London and New York City. What’s Paris got that your city hasn’t got? Is it the nickname the City of Love? Is it the slogan Liberty Started Here or the idea that Life is an Art with images of famous artists like Monet, Modigliani, Dali, da Vinci, Picasso, Braque and Klee? Is it the Cole Porter song, I Love Paris, sung by Frank Sinatra? Is it the movie American in Paris? Is it the fact that Paris has numerous architectural icons that sum up the city’s identity and image --- the Eiffel Tower, Arch of Triumph, Notre Dame Cathedral, Moulin Rouge and Palace of Versailles? Do cities need icons, songs, slogans and nicknames to become famous? Or do famous cities simply attract more attention from architects, artists, wordsmiths and ad agencies? Certainly, having an architectural icon, such as the Eiffel Tower, built in 1889, put Paris on the world map. But all these other things were added to make the identity and image. As a result, international tourists spent $46.3 billion in France in 2010. What’s your city’s claim to fame? Does it have an architectural icon? World’s Most Famous City Icons Beyond nicknames, slogans and songs, some cities are fortunate to have an architectural icon that is immediately recognized by almost everyone worldwide. -

Tall Buildings Tall Building Projects Worldwide

Tall buildings Safe, comfortable and sustainable solutions for skyscrapers ©China Resources Shenzhen Bay Development Co., Ltd ©China Resources Tall building projects worldwide Drawing upon our diverse skillset, Arup has helped define the skylines of our cities and the quality of urban living and working environments. 20 2 6 13 9 1 7 8 16 5 11 19 3 15 10 17 4 12 18 14 2 No. Project name Location Height (m) 1 Raffles City Chongqing 350 ©Safdie Architect 2 Burj Al Alam Dubai 510 ©The Fortune Group/Nikken Sekkei 3 UOB Plaza Singapore 274 4 Kompleks Tan Abdul Razak Penang 232 5 Kerry Centre Tianjin 333 ©Skidmore Owings & Merrill 6 CRC Headquarters Shenzhen 525 ©China Resources Shenzhen Bay Development Co Ltd 7 Central Plaza Hong Kong 374 8 The Shard London 310 9 Two International Finance Centre Hong Kong 420 10 Shenzhen Stock Exchange Shenzhen 246 ©Marcel Lam Photography 11 Wheelock Square Shanghai 270 ©Kingkay Architectural Photography 12 Riviera TwinStar Square Shanghai 216 ©Kingkay Architectural Photography 13 China Zun (Z15) Beijing 528 ©Kohn Pederson Fox Associates PC 14 HSBC Main Building Hong Kong 180 ©Vanwork Photography 15 East Pacific Centre Shenzhen 300 ©Shenzhen East Pacific Real Estate Development Co Ltd 16 China World Tower Beijing 330 ©Skidmore, Owings & Merrill 17 Commerzbank Frankfurt 260 ©Ian Lambot 18 CCTV Headquarters Beijing 234 ©OMA/Ole Scheeren & Rem Koolhaas 19 Aspire Tower Doha 300 ©Midmac-Six Construct 20 Landmark Tower Yongsan 620 ©Renzo Piano Building Workshop 21 Northeast Asia Trade Tower New Songdo City 305 ©Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates PC 22 Guangzhou International Finance Centre Guangzhou 432 ©Wilkinson Eyre 23 Torre Reforma Mexico 244 ©L Benjamin Romano Architects 24 Chow Tai Fook Centre Guangzhou 530 ©Kohn Pederson Fox Associates PC 25 Forum 66 Shenyang 384 ©Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates PC 26 Canton Tower Guangzhou 600 ©Information Based Architecture 27 30 St. -

RESULTS 60 Metres Men - Round 1 First 3 in Each Heat (Q) and the Next 3 Fastest (Q) Advance to the Semi-Finals WORLD INDOOR RECORD PENDING RATIFICATION

Birmingham (GBR) World Indoor Championships 1-4 March 2018 RESULTS 60 Metres Men - Round 1 First 3 in each heat (Q) and the next 3 fastest (q) advance to the Semi-Finals WORLD INDOOR RECORD PENDING RATIFICATION RECORDS RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE VENUE DATE World Indoor Record WIR 6.34 Christian COLEMAN USA 22 Albuquerque (USA) 18 Feb 2018 Championship Record CR 6.42 Maurice GREENE USA 25 Maebashi (Green Dome) 7 Mar 1999 World Leading WL 6.34 Christian COLEMAN USA 22 Albuquerque (USA) 18 Feb 2018 Area Indoor Record AIR National Indoor Record NIR Personal Best PB Season Best SB 3 March 2018 10:15 START TIME Heat 1 7 PLACE NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH LANE RESULT REACTION Fn 1 Christian COLEMAN USA 6 Mar 96 6 6.71 (.708) Q 0.137 2 Odain ROSE SWE 19 Jul 92 7 6.75 Q 0.160 3 Kim COLLINS SKN 5 Apr 76 4 6.77 (.770) Q 0.219 4 Jonah HARRIS NRU 16 Jan 99 8 7.03 (.027) NIR 0.147 5 Jacob EL AIDA MLT 8 Nov 01 5 7.09 0.156 6 Zdenek STROMŠÍK CZE 25 Nov 94 3 7.41 0.155 Kemar HYMAN CAY 11 Oct 89 2 DQ 162.8 -0.335 F1 NOTE IAAF Rule 162.8 - False Start 3 March 2018 10:22 START TIME Heat 2 7 PLACE NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH LANE RESULT REACTION Fn 1 Bingtian SU CHN 29 Aug 89 4 6.59 (.586) Q 0.163 2 Warren FRASER BAH 8 Jul 91 8 6.71 (.703) Q 0.134 3 Kimmari ROACH JAM 21 Sep 90 7 6.71 (.707) Q 0.194 4 Peter EMELIEZE GER 19 Apr 88 6 6.77 (.763) 0.150 5 Keston BLEDMAN TTO 8 Mar 88 2 6.79 0.161 6 Juan Carlos RODRIGUEZ MARROQUIN ESA 19 Dec 94 5 7.03 (.027) NIR 0.191 7 Holder Ocante DA SILVA GBS 22 Jan 88 3 7.20 SB 0.196 3 March 2018 10:27 START TIME Heat 3 7 PLACE NAME -

Comparing the Structural System of Some Contemporary High Rise Building Form

Comparing the structural system of some contemporary high rise building form Presented From Researcher : Aya Alsayed Abd EL-Tawab Graduate Researcher in Faculty of Engineering - Fayoum University Email:[email protected]. Study of vertical and horizontal expansion of Abstract buildings and development of large-scale Throughout history, human beings have built tall buildings. monumental structures such as temples, pyramids Research Methodology: and cathedrals to honour their gods. The research methodology was based on Today’s skyscrapers are monumental buildings theoretical and analytical Side: too, and are built as symbols of power, wealth and Theoretically The methodology of the study was prestige. based on a combination of different structural These buildings emerged as a response to the systems suitable for vertical expansion . rapidly growing urban population. Comparison between the different construction Architects’ creative approaches in their designs systems and the design of the buildings in high for tall buildings, the shortage and high cost of altitude urban land, the desire to prevent disorderly urban Analytically Study of some examples of high expansion, have driven the increase in the height buildings Identification of the elements of of buildings. comparison between the spaces of the various The Research Problem:The increase in the systems of the construction of towers such as: the height of buildings makes them vulnerable to possibilities of internal divisions and the opening wind and earthquake induced lateral loads. of spaces on some, , the heights of tower spaces occupancy comfort (serviceability) are also on all roles, the formation of the tower block, among the foremost design inputs . internal movement, spatial needs of services. -

Signature Redacted Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 21, 2015

TRENDS AND INNOVATIONS IN HIGH-RISE BUILDINGS OVER THE PAST DECADE ARCHIVES 1 by MASSACM I 1TT;r OF 1*KCHN0L0LGY Wenjia Gu JUL 02 2015 B.S. Civil Engineering University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 LIBRAR IES SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ENGINEERING IN CIVIL ENGINEERING AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2015 C2015 Wenjia Gu. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known of hereafter created. Signature of Author: Signature redacted Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 21, 2015 Certified by: Signature redacted ( Jerome Connor Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted bv: Signature redacted ?'Hei4 Nepf Donald and Martha Harleman Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Chair, Departmental Committee for Graduate Students TRENDS AND INNOVATIONS IN HIGH-RISE BUILDINGS OVER THE PAST DECADE by Wenjia Gu Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 21, 2015 in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Requirements for Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering ABSTRACT Over the past decade, high-rise buildings in the world are both booming in quantity and expanding in height. One of the most important reasons driven the achievement is the continuously evolvement of structural systems. In this paper, previous classifications of structural systems are summarized and different types of structural systems are introduced. Besides the structural systems, innovations in other aspects of today's design of high-rise buildings including damping systems, construction techniques, elevator systems as well as sustainability are presented and discussed. -

Investigation of Passive Control of Irregular Building Structures Using Bidirectional Tuned Mass Damper

INVESTIGATION OF PASSIVE CONTROL OF IRREGULAR BUILDING STRUCTURES USING BIDIRECTIONAL TUNED MASS DAMPER THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mariantonieta Gutierrez Soto Graduate Program in Civil Engineering The Ohio State University 2012 Master's Examination Committee: Dr. Hojjat Adeli, Advisor Dr. Ethan Kubatko Dr. Vadim Utkin Copyright by Mariantonieta Gutierrez Soto 2012 ABSTRACT Eight different sets of equations proposed for tuning the parameters of tuned mass dampers (TMDs) are compared using a 5-story building with plan and elevation irregularity, and a 15-story and a 20-story building with plan irregularity subjected to seismic loading. Next, the performance of bidirectional tuned mass damper (BTMD) is compared with that of the pendulum tuned mass damper (PTMD) using three different structures with plan and vertical irregularities ranging in height from 5 to 20 stories and dominant fundamental periods ranging from 0.55 sec to 4.25 sec subjected to Loma Prieta earthquake. It is concluded that BTMD performs consistently better than PTMD for reduction of maximum displacement, acceleration and base shear. BTMD is advantageous over PTMD because it can be tuned for two modes of vibrations and therefore can be used as an alternative to using two TMDs. Then, the effectiveness of BTMD is investigated using a 20-story building structure with plan irregularity subjected to six seismic accelerograms. Finally, the optimal placement of the BTMD is investigated using five different multi-story building structures with plan and elevation irregularities ranging in height from 5 to 20 stories and fundamental periods ranging from 0.55 sec to 4.25 sec subjected to Loma Prieta earthquake. -

High Rise: Our Expertise

HIGH-RISE OUR EXPERTISE 15,000 110 EMPLOYEES WORLDWIDE YEARS’ EXPERIENCE 70+ 5 NATIONALITIES CONTINENTS N°69 2 billion+ INTERNATIONAL CONTRACTOR OF SALES ENR TOP 250 RANKING Cover picture: Burj Khalifa, Dubai, UAE Picture below: New Orleans, Rotterdam, The Netherlands 02 BESIX GROUP EXCELLING IN CREATING SUSTAINABLE SOLUTIONS FOR A BETTER WORLD BESIX is a leading Belgian business group, operating on BESIX is an international reference in the building, maritime five continents in construction, real estate development works, environment, sports and leisure facilities, industrial and concessions. buildings, road, rail, port and airport sectors. The Group is currently working on dozens of projects in around Its iconic achievements include Dubai’s Burj Khalifa, the 25 countries on five continents. world’s tallest tower; the Grand Egyptian Museum on the Giza pyramids plateau; the Ferrari World Leisure Center in Abu Its policy of sector diversification is also bearing fruit. Dhabi, the Carpe Diem building in Paris’s La Défense district; Its Concessions & Assets activities have taken off in recent the Al Wakrah Stadium, built for the FIFA World Cup Qatar years. BESIX’s expertise allows it to handle projects from 2022; and the Jebel Ali water treatment plant, an ongoing financial structuring to design and construction through project that will treat Dubai’s entire wastewater to the highest to maintenance. For its part, the Real Estate Development environmental standards. activity led by BESIX RED offers innovative real estate solutions in the residential, commercial and office sectors in five European countries. BESIX’s unique expertise is ensured by it having an in-house Engineering Department, at the forefront of contemporary technologies. -

One World, One Vision Eine Welt, Eine Vision One World, One Vision Corus One World 14.02.2008 17:33 Uhr Seite 136 Corus One World 14.02.2008 17:11 Uhr Seite 1

Eine Welt, eine Vision Eine Welt, One world, one vision Eine Welt, eine Vision One world, one vision Corus One World 14.02.2008 17:33 Uhr Seite 136 Corus One World 14.02.2008 17:11 Uhr Seite 1 One world, one vision Eine Welt, eine Vision Published by Corus Distribution & Building Systems – Kalzip Business Unit Veröffentlicht durch Corus Distribution & Building Systems – Kalzip Business Unit Corus One World 14.02.2008 17:11 Uhr Seite 2 Welcome 4 One idea 6 Award-winning construction with Kalzip 6 One vision 8 Construction now and tomorrow 22 One future 26 Innovation and research 26 One world 32 Projects 34 40 years of Kalzip – 40 years of excellence 120 Further information 132 Acknowledgements 134 2 Corus One World 14.02.2008 17:11 Uhr Seite 3 Contents Inhalt Willkommen 4 Eine Idee 6 Preisgekröntes Bauen mit Kalzip 6 Eine Vision 8 Bauen heute und morgen 22 Eine Zukunft 26 Innovation und Forschung 26 Eine Welt 32 Projekte 34 40 Jahre Kalzip – 40 years of excellence 120 Informationen 132 Impressum 134 3 Corus One World 15.02.2008 12:59 Uhr Seite 4 The face of construction is changing. Ambitious political commit- consistently and progressively supporting the team through ments, progressively tightening regulations and an increasingly design and construction to hand over. complicated industry are creating a unique set of challenges and Commitment, trust and common goals have been, and continue standards. Far reaching targets of today will be the norm tomor- to be vital to the future success of the company. Kalzip is row as the industry drives to deliver a more social, economic and passionate about embracing new technologies, higher standards environmentally conscious platform for ‘responsible’ buildings. -

World Indoor Championships - Doha 2010

Media Guide Doha 2010 Aspire Dome 12 - 14 March 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome Messages IAAF President LOC President LOC Media & Broadcasting Manager 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 1.1 IAAF Council Members 1.2 IAAF Delegates 1.3 IAAF Communications & Broadcasting Staff On-Site 1.4 Local Organising Committee 1.5 Local Media & Broadcasting Division 2. TRAVEL TO QATAR 2.1 Entry Visas 2.2 Prohibited Items 3. DOHA WIC 2010 – OVERVIEW 3.1 The World Indoors in Brief 3.2 Mascot 3.3 Medals 3.4 Aspire Dome 4. MEDIA ACCREDITATION 4.1 Main Accreditation Centre 4.2 Accreditation Procedures 4.3 Loss of Accreditation Card 5. MEDIA TRANSPORTATION 5.1 Media Transportation Arrangements 5.2 Travel Times 5.3 Public Transport Page 1 IAAF World Indoor Championships - Doha 2010 6. MEDIA ACCOMMODATION 6.1 Media Hotels 6.2 Payment Procedure 6.3 Changes and Cancellations 6.4 Services in the Media Hotels 7. MEDIA SERVICES & FACILITIES 7.1 Main Media Centre Welcome & Information Desks Press Work Area Photo Work Area Press Tribune Mixed Zone Photo Positions Press Conference Room News Service Media Restaurant Media Lounge 7.2 Sub-Media Centre 8. BROADCASTING SERVICES & FACILITIES 8.1 International Broadcast Centre 8.2 Broadcast Infield Studios 8.3 Commentary Positions 8.4 TV Mixed Zone 9. MEDIA SPECIFIC ACTIVITIES 9.1 TV Rehearsal 9.2 IAAF/LOC Press Conference 9.3 TV Briefing 9.4 Photo Briefing 9.5 Detailed Schedule 10. MEDIA TOURS 11. TIMETABLE Page 2 12. ENTRY STANDARDS 13. COMPETITION AWARDS 14. 2010 RULE CHANGES 15. RECORDS 16. -

February 07, 2018

SPORT Wednesday 7 February 2018 PAGE | 30 PAGE | 31 PAGE | 32-33 Injured Mathews Pyeongchang ready PSG pay 12 of ruled out of to battle cold snap, highest Ligue 1 Bangladesh tour norovirus: Lee salaries Sanchez confident Al Annabi will be ready for Qatar 2022 REUTERS and experience to face this with the level in the first division in Belgium right mood to play in this or the second division in Spain. HONG KONG: Qatar will take a competition.” They’re both very good levels. huge stride into the unknown Qatar have gone close twice to “It gives them the opportu- when they host the World Cup in qualify for World Cup, with their It (playing in Europe) gives nity to grow as players and so 2022 but coach Felix Sanchez is most recent near-miss coming them the opportunity to far we are trying different confident the players will gain ahead of the 1998 finals when a grow as players and so players there and all the enough experience in the lead-up narrow defeat at the hands of Saudi far we are trying different experiences have been to the showpiece event to not get Arabia cost the nation a place in players there and all the very positive and that’s the overawed at their first finals France. experiences have been most important thing.” appearance. Qatar were awarded the host- Sanchez is hoping Qatar missed out on qualify- ing rights for the 2022 tournament very positive and that’s the experience will ing for Russia this summer, in December 2010, prompting the most important thing: begin to pay off when ensuring they will make their debut authorities to improve an already Sanchez he leads the senior appearance at the tournament burgeoning development set-up.