Tall Buildings, Design, and Technology Visions for the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presentation Slides

A Developer’s Perspective of Creating a Healthy Community for All Ages Friday, May 7, 2021 Delivering more, through balance 3 Triple Chinachem Group takes tremendous pride in its balanced approach to business. We operate not solely for profit, but with the higher aim of Bottom Line contributing to society. We want to create positive value for our users and customers, the community and the environment, thereby achieving the triple bottom line of benefits to People, Prosperity and Planet. People Prosperity Planet 4 How a triple bottom line works? 5 Sustainability PEOPLE Principles To engage stakeholders and staff, while respecting each other, in contributing to sustainable development as well Derived From as nurturing diversity and a culture of inclusiveness in Triple Bottom communities Line PROSPERITY To deliver products and services that meet the community's current and future needs in a safe, efficient and sustainable manner, and to make our city more liveable and sustainable PLANET To integrate environmental considerations into all aspects of planning, design and operations for minimising resource and energy consumption as well as reducing the environmental impacts "Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” United Nations 1987 Brundtland Commission Report 7 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals The Group makes reference to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in developing its short, medium and long-term goals 8 Carbon The Strategic Roadmaps and Sustainability Plan (CCG3038) was developed in 2019 Reduction Target - All business units should provide their roadmaps to achieve the group target of 38% carbon emissions reduction in 2030 as compared with 2015. -

Structural Developments in Tall Buildings: Current Trends and Future Prospects

© 2007 University of Sydney. All rights reserved. Architectural Science Review www.arch.usyd.edu.au/asr Volume 50.3, pp 205-223 Invited Review Paper Structural Developments in Tall Buildings: Current Trends and Future Prospects Mir M. Ali† and Kyoung Sun Moon Structures Division, School of Architecture, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL 61820, USA †Corresponding Author: Tel: + 1 217 333 1330; Fax: +1 217 244 2900; E-mail: [email protected] Received 8 May; accepted 13 June 2007 Abstract: Tall building developments have been rapidly increasing worldwide. This paper reviews the evolution of tall building’s structural systems and the technological driving force behind tall building developments. For the primary structural systems, a new classification – interior structures and exterior structures – is presented. While most representative structural systems for tall buildings are discussed, the emphasis in this review paper is on current trends such as outrigger systems and diagrid structures. Auxiliary damping systems controlling building motion are also discussed. Further, contemporary “out-of-the-box” architectural design trends, such as aerodynamic and twisted forms, which directly or indirectly affect the structural performance of tall buildings, are reviewed. Finally, the future of structural developments in tall buildings is envisioned briefly. Keywords: Aerodynamics, Building forms, Damping systems, Diagrid structures, Exterior structures, Interior structures, Outrigger systems, Structural performance, Structural systems, Tall buildings Introduction Tall buildings emerged in the late nineteenth century in revolution – the steel skeletal structure – as well as consequent the United States of America. They constituted a so-called glass curtain wall systems, which occurred in Chicago, has led to “American Building Type,” meaning that most important tall the present state-of-the-art skyscraper. -

An Overview of Structural & Aesthetic Developments in Tall Buildings

ctbuh.org/papers Title: An Overview of Structural & Aesthetic Developments in Tall Buildings Using Exterior Bracing & Diagrid Systems Authors: Kheir Al-Kodmany, Professor, Urban Planning and Policy Department, University of Illinois Mir Ali, Professor Emeritus, School of Architecture, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Subjects: Architectural/Design Structural Engineering Keywords: Structural Engineering Structure Publication Date: 2016 Original Publication: International Journal of High-Rise Buildings Volume 5 Number 4 Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Kheir Al-Kodmany; Mir Ali International Journal of High-Rise Buildings International Journal of December 2016, Vol 5, No 4, 271-291 High-Rise Buildings http://dx.doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2016.5.4.271 www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php An Overview of Structural and Aesthetic Developments in Tall Buildings Using Exterior Bracing and Diagrid Systems Kheir Al-Kodmany1,† and Mir M. Ali2 1Urban Planning and Policy Department, University of Illinois, Chicago, IL 60607, USA 2School of Architecture, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL 61820, USA Abstract There is much architectural and engineering literature which discusses the virtues of exterior bracing and diagrid systems in regards to sustainability - two systems which generally reduce building materials, enhance structural performance, and decrease overall construction cost. By surveying past, present as well as possible future towers, this paper examines another attribute of these structural systems - the blend of structural functionality and aesthetics. Given the external nature of these structural systems, diagrids and exterior bracings can visually communicate the inherent structural logic of a building while also serving as a medium for artistic effect. -

Une Course Vers Le Ciel. Mondialisation Et Diffusion Spatio-Temporelle Des Gratte-Ciel

M@ppemonde Une course vers le ciel. Mondialisation et diffusion spatio-temporelle des gratte-ciel Clarisse Didelon UMR 6228 IDEES – Équipe CIRTAI CNRS, Université du Havre « Nous construisons à une hauteur qui rivalisera avec la tour de Babel ». William Le Baron Jenney, 1883 (cité par Judith Dupré, 2005) « Les signes s’exposent dans une matière, une forme et plastique qui ont une double fonction d’usage et de représentation ». Armand Frémont, 1976 Résumé.— La construction de gratte-ciel a des ressorts aussi bien fonctionnels que symboliques. Les gratte-ciel trouvent sens à l’échelle locale, nationale mais aussi à l’échelle mondiale. L’analyse de la diffusion spatio-temporelle de la construction de gratte-ciel met en évidence leurs liens forts avec les contextes économiques et idéologiques et souligne dans une certaine mesure la convergence des modes de vie de la population mondiale. Gratte-ciel • Diffusion spatio-temporelle • Monde Abstract.— A Race to the Sky. Globalization and the Spatiotemporal Diffusion of Skyscrapers.— The building of skyscrapers has both functional and symbolic meaning. Skyscrapers have a certain level of significance at the local, national but also world level. The analysis of spatiotemporal diffusion of skyscrapers underlines strong links with the economical and ideological background and more, in a certain sense the convergence of the world population way of life. Skyscrapers • Spatiotemporal diffusions • World Resumen.— Una carrera hacia el cielo. Mundializacion y difusion espacio-temporal de los rascacielos.— La construccion de rascacielos tiene rasgos tanto funcionales como simbolicos. Los rascacielos tienen sentido a las escalas local, nacional pero tambien mundial. El analisis de su difusion espacio-temporal pone en evidencia su fuerte relacion con los entornos economicos e ideologicos, y, en cierta medida, pone enfasis en la convergencia de modos de vida de la poblacion mundial. -

News Brief 47 Sunday, 19 November 2017

ASSET MANAGEMENT SALES LEASING VALUATION & ADVISORY SALES MANAGEMENT OWNER ASSOCIATION NEWS BRIEF 47 SUNDAY, 19 NOVEMBER 2017 RESEARCH DEPARTMENT DUBAI | ABU DHABI | AL AIN | SHARJAH | JORDAN IN THE MIDDLE EAST FOR 30 YEARS © Asteco Property Management, 2017 asteco.com | astecoreports.com ASSET MANAGEMENT SALES LEASING VALUATION & ADVISORY SALES MANAGEMENT OWNER ASSOCIATION REAL ESTATE NEWS UAE / GCC QATAR FACES WORST DECLINE IN GCC REAL ESTATE SECTOR DSI REPORTS DH359M LOSS IN THIRD QUARTER A CHAIN THAT LIBERATES THE AFFORDABILITY ANGLE: A CONSUMER’S VIEW UNION PROPERTIES POSTS LOSS ON SUBSIDIARY CLOSURE RULES TIGHTENED FOR OFF-PLAN PROPERTY BUYERS IN DUBAI 'MY MOULDY APARTMENT IS MAKING ME SICK BUT THE AGENCY IS REFUSING TO CLEAN IT UP' STRUGGLING QATARI DEVELOPER SHED JOBS AMID SLUMP JOB VACANCIES RISE ACROSS MIDDLE EAST DUBAI CLASSIFICATION OF BUILDINGS IN DUBAI’S OLDER AREAS IN FINAL STRETCH THE LANGHAM EXPERIENCE MAKING SENSE OF A SLOW MARKET FROM HUMBLE ABRA STEPS TO SKY-HIGH ICONS A FURTHER 163,000 HOMES IN THE PIPELINE FOR DUBAI DOMESTIC SALES GAINS BOOST EMAAR’S NET PROFIT A PRIMER ON DUBAI RENTAL INDEX CALCULATIONS EMAAR DEVELOPMENT LPO RAISES DH4.8 BILLION IN LARGEST DUBAI LISTING IN THREE YEARS DH30M DUBAI APARTMENT COULD BE BUSINESS BAY'S FINEST EMAAR THIRD QUARTER NET PROFIT SOARS 32%, BEATS ANALYSTS' FORECASTS WASL LAUNCHES 3RD TOWER FOR SALE AT PARK GATE RESIDENCES DAMAC LAUNCHES VILLAS FOR DH2.5 MILLION DUBAI HOSPITALITY SECTOR TO SEE ADDITION OF 29,200 KEYS ABU DHABI HOME HUNTING ON THE YAS ISLAND ALDAR RECORDS DH601M -

IBIS Deira City Center / IBIS Al Rigga Hotel / IBIS – WTC / IBIS

Hotels Avail for Transportation Central Dubai 2 Star Hotel: IBIS Deira City Center / IBIS Al Rigga Hotel / IBIS – WTC / IBIS – AL Barsha / Holiday Inn Express Airport hotel / Holiday Inn Express SAFA park / Holiday Inn Express Jumeirah 3 Star Hotel: Arabian Park Hotel / London Crown Hotel / City max Hotel – Bur Dubai / City max hotel -Al Basha / Howard Johnson Hotel / Admiral Plaza 4 Star Hotel: Al Jawhra Gardend / Al Kaleej Palace Hotel / Arabian Courtyard Hotel / Riviera Hotel / Sheraton Deira hotel / Ascot Hotel / Royal Ascot hotel / Traders hotel / Majestic Hotel / Four point Sheraton –Bur Dubai / Four points Sheraton – Down Town / Four point Sheraton Sheikh Zayed Hotel / Radisson BLU Downtown Hotel / Radisson BLU Deira creek hotel / Rose Rayhaan by Rotana / Towers Rotana Hotel / Burjuman Rotana Hotel / AL Manzil Down Town / Vida Downtown hotel / Avari Hotel / Avenue Hotel / Carlton Towers hotel / City Season hotel / Coral Deira Hotel /Cosmopolitan Hotel /Double Tree by Hilton Hotel & Residence Al barsha / Emirates Concorde Hotel /Emirates Grand Hotel /Flora Grand Hotel / Five Continent Cassells Al Basha / Fortune Boutique Hotel / Holiday Inn –Bur Dubai / Holiday Inn –Al Basha / Holiday Inn Downtown / Hyatt place Hotel / Landmark hotel /Marco polo Hotel / Novotel Deira City Center / Novotel WTC / Novotel Al Basha hotel / Ramada Chelsea Hotel / Ramada Deira hotel / Mercure Gold Hotel / Millennium Airport Hotel Dubai / Barjeel Guests House / Orient Guests House, etc. 5 Star Hotel: Armani Dubai / Hyatt Regency Hotel / Grand Hyatt hotel -

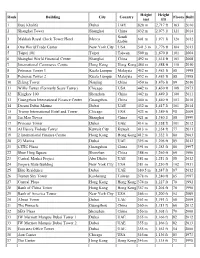

List of World's Tallest Buildings in the World

Height Height Rank Building City Country Floors Built (m) (ft) 1 Burj Khalifa Dubai UAE 828 m 2,717 ft 163 2010 2 Shanghai Tower Shanghai China 632 m 2,073 ft 121 2014 Saudi 3 Makkah Royal Clock Tower Hotel Mecca 601 m 1,971 ft 120 2012 Arabia 4 One World Trade Center New York City USA 541.3 m 1,776 ft 104 2013 5 Taipei 101 Taipei Taiwan 509 m 1,670 ft 101 2004 6 Shanghai World Financial Center Shanghai China 492 m 1,614 ft 101 2008 7 International Commerce Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 484 m 1,588 ft 118 2010 8 Petronas Tower 1 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 8 Petronas Tower 2 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 10 Zifeng Tower Nanjing China 450 m 1,476 ft 89 2010 11 Willis Tower (Formerly Sears Tower) Chicago USA 442 m 1,450 ft 108 1973 12 Kingkey 100 Shenzhen China 442 m 1,449 ft 100 2011 13 Guangzhou International Finance Center Guangzhou China 440 m 1,440 ft 103 2010 14 Dream Dubai Marina Dubai UAE 432 m 1,417 ft 101 2014 15 Trump International Hotel and Tower Chicago USA 423 m 1,389 ft 98 2009 16 Jin Mao Tower Shanghai China 421 m 1,380 ft 88 1999 17 Princess Tower Dubai UAE 414 m 1,358 ft 101 2012 18 Al Hamra Firdous Tower Kuwait City Kuwait 413 m 1,354 ft 77 2011 19 2 International Finance Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 412 m 1,352 ft 88 2003 20 23 Marina Dubai UAE 395 m 1,296 ft 89 2012 21 CITIC Plaza Guangzhou China 391 m 1,283 ft 80 1997 22 Shun Hing Square Shenzhen China 384 m 1,260 ft 69 1996 23 Central Market Project Abu Dhabi UAE 381 m 1,251 ft 88 2012 24 Empire State Building New York City USA 381 m 1,250 -

22/F One Lujiazui, 68 Yin Cheng Road, Shanghai

22/F One Lujiazui, 68 Yin Cheng Road, Shanghai View this office online at: https://www.newofficeasia.com/details/offices-one-lujiazui-yin-cheng-road-chi na This prominent building towers almost 270 metres over Lujiazui Central Park, in the heart of the Pudong business hub in Shanghai, becoming the centrepiece of an iconic city skyline. These serviced offices can be found on the 22nd storey providing spectacular views of the greenery of the park and beyond to the Bund. The centre is designed to suit the needs of every type of business, large or small. Office spaces range from furnished individual work spaces to larger, more conventional office suites including executive suites, yet all providing a calm and comfortable environment conducive to working efficiently. All in all this is a great opportunity to run your business from a great business environment with flexible service agreements and rental rates. Transport links Nearest tube: Lujiazui station (metro line 2) Nearest railway station: Shanghai Station Nearest road: Lujiazui station (metro line 2) Nearest airport: Lujiazui station (metro line 2) Key features 24 hour access Administrative support AV equipment Car parking spaces Close to railway station Conference rooms Conference rooms High speed internet High-speed internet IT support available Meeting rooms Modern interiors Near to subway / underground station Reception staff Security system Telephone answering service Town centre location Unbranded offices Video conference facilities Location This business centre isl located right in the heart of the financial area of Lujiazui. With all amenities on the doorstep including banks, bars, grocery stores, restuarants etc, plus neighbouring the Lujiazui Central Park, ths area is well served by public transport including Lujiazui station (metro line 2) and bus services. -

CTBUH Journal

CTBUH Journal Tall buildings: design, construction and operation | 2008 Issue III China Central Television Headquarters The Vertical Farm Partial Occupancies for Tall Buildings CTBUH Working Group Update: Sustainability Tall Buildings in Numbers Moscow Gaining Height Conference Australian CTBUH Seminars Editor’s Message The CTBUH Journal has undergone a major emerging trend. A number of very prominent cases transformation in 2008, as its editorial board has are studied, and fundamental considerations for sought to align its content with the core objectives each stakeholder in such a project are examined. of the Council. Over the past several issues, the journal editorial board has collaborated with some of the most innovative minds within the field of tall The forward thinking perspectives of our authors in building design and research to highlight new this issue are accompanied by a comprehensive concepts and technologies that promise to reshape survey of the structural design approach behind the the professional landscape for years to come. The new China Central Television (CCTV) Tower in Beijing, Journal now contains a number of new features China. The paper, presented by the chief designers intended to facilitate discourse amongst the behind the tower structure, explores the membership on the subjects showcased in its pages. groundbreaking achievements of the entire design And as we enter 2009, the publication is poised to team in such realms as computational analysis, achieve even more as brilliant designers, researchers, optimization, interpretation and negotiation of local builders and developers begin collaboration with us codes, and sophisticated construction on papers that present yet-to-be unveiled concepts methodologies. -

City Branding: Part 2: Observation Towers Worldwide Architectural Icons Make Cities Famous

City Branding: Part 2: Observation Towers Worldwide Architectural Icons Make Cities Famous What’s Your City’s Claim to Fame? By Jeff Coy, ISHC Paris was the world’s most-visited city in 2010 with 15.1 million international arrivals, according to the World Tourism Organization, followed by London and New York City. What’s Paris got that your city hasn’t got? Is it the nickname the City of Love? Is it the slogan Liberty Started Here or the idea that Life is an Art with images of famous artists like Monet, Modigliani, Dali, da Vinci, Picasso, Braque and Klee? Is it the Cole Porter song, I Love Paris, sung by Frank Sinatra? Is it the movie American in Paris? Is it the fact that Paris has numerous architectural icons that sum up the city’s identity and image --- the Eiffel Tower, Arch of Triumph, Notre Dame Cathedral, Moulin Rouge and Palace of Versailles? Do cities need icons, songs, slogans and nicknames to become famous? Or do famous cities simply attract more attention from architects, artists, wordsmiths and ad agencies? Certainly, having an architectural icon, such as the Eiffel Tower, built in 1889, put Paris on the world map. But all these other things were added to make the identity and image. As a result, international tourists spent $46.3 billion in France in 2010. What’s your city’s claim to fame? Does it have an architectural icon? World’s Most Famous City Icons Beyond nicknames, slogans and songs, some cities are fortunate to have an architectural icon that is immediately recognized by almost everyone worldwide. -

UAE Star Network.Pdf

STAR NETWORK UNITED ARAB EMIRATES Direct Billing Treatment allowed in the below facilities Medical Center Location Contact No Specialty ABU DHABI (+971 2) Abu Salman Medical Center Mussafah Shabiya Khalifa Sector 10 02-552 2549 GP & Dental 1st Floor Al Otaiba Building, First Sayed Adam & Eve Specialized Medical Center 02-676 7366 Dental Street Villa No. 6, Block 42-Z12, Mohd Bin Zayed Add Care Medical Centre 02-555 5599 Multispecialty City Advanced Center for Daycare Surgery 1st Floor Jasmine Tower, Airport Road 02-622 7700 Multispecialty Al Khaleej Al Arabi Street, Mohammed Bin Advanced Cure Diagnostic Center 02-667 5050 Multispecialty Mejren Building Advanced Cure Diagnostic Center - 32nd Street, Al Bateen Area, 4th Villa 02-410 0990 Multispecialty Branch Aesthetic Dental Centre LLC Electra Street, Al Markaziya 02-632 4455 Dental Ahalia Hospital Hamdan Street, opposite Bank of Baroda 02-626 2666 Multispecialty Emirates Kitchen Equipment Bldg, Flat 30, Ailabouni Medical Center 02-644 0125 Multispecialty Al Salam Street Al Ahali Medical Centre Muroor Road 4th Street, Khalfan Matar 02-641 7300 Dental Al Ahli Hospital Company Branch-1 Liwa Road, Mussafah 02-811 9119 Multispecialty Electra Street, Naseer Al Mansoori Bldg., Al Ameen Medical Centre 02-633 9722 Multispecialty First Floor, Flat #103 Laboratory and Al Borg Medical Laboratory for Diagnostic 1st Floor, Bin Arar Building, Najda Street 02-676 1221 Diagnostics Al Daleel Dental Clinic Al Khaili Bldg., Defense Street 02-445 5884 Dental Beda Zayed, Western Region, Industrial Al Dhafra Modern Clinic 02-884 6651 GP Area Al Falah Medical Center Elektra Street 02-621 1814 Multispecialty Al Hendawy Medical Center 4F & 10F ADCB Bldg., Al Muroor Road 02-621 3666 Multispecialty Al Hikma Medical Centre LLC Hamdan Street, Abu Dhabi 02-672 0482 Multispecialty Al Hikma Medical Centre LLC Branch 1 Mushrief Area, Al Khaleel Street 02-447 4435 Multispecialty Network List is subject to change. -

Tall Can Be Beautiful

The Financial Express January 10, 2010 7 INDIA’S VERTICAL QUEST TALLCANBEBEAUTIFUL SCRAPINGTHE PreetiParashar 301m)—willbecompleted. FSI allowed is 1.50-2.75 in all metros and meansprojectswillbecheaperonaunit-to- ronment-friendly. ” KaizerRangwala mid-risebuildings.ThisisbecauseIndian TalltowersshouldbedesignedfortheIndi- SKY, FORWHAT? Of the newer constructions,the APIIC ground coverage is 30-40%. It is insuffi- unit basis and also more plentiful in prof- “There is a need for more service pro- cities have the lowest floor space index an context. They should take advantage of S THE WORLD’S Tower (Andhra Pradesh Industrial Infra- cient to build skyscrapers here.”He adds, itable areas,which is good news for viders of eco-friendly construction mate- Winston Churchill said, (FSI), in the world. Government regula- thelocalclimate—rainfall,light,ventilation, tallest building, the structure Corporation Tower) being built “The maximum height that can be built investors and the buyers.However, allow- rials toreducecosts,”saysPeriwal. “We make our buildings tions thatallowspecific number of build- solar orientation without sacrificing the KiranYadav theleadafterWorldWarI—again,aperiod 828-metreBurjKhalifa, at Hyderabadisexpectedtobea100-storey (basedonperacrescalculation)isapproxi- ing high-rises indiscriminately in certain However Sandhir thinks of high-rises and afterwards they make ing floors based on the land area, thus street-levelorientationof buildings;history; marked by economic growth and techno- alters the skyline of buildingwithaheightof