Daimyo Culture in Peacetime, August 17, 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Images and Words. an Interdisciplinary Unit for Sixth-Grade Art and Language Arts Classes

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 391 771 SO 026 096 AUTHOR Lyons, Nancy Hai,:te; Ridley, Sarah TITLE Japan: Images and Words. An Interdisciplinary Unit for Sixth-Grade Art and Language Arts Classes. INSTITUTION Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. PUB DATE 94 NOTE 66p.; Color slides and prints not included in this document. AVAILABLE FROM Education Department, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560 ($24 plus $4.50 shipping and handling; packet includes six color slides and six color prints). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Art; Art Activities; Art Appreciation; *Art Education; Foreign Countries; Grade 6; *Interdisciplinary Approach; Intermediate Grades; *Japanese Culture; *Language Arts; Painting (Visual Arts) ;Visual_ Arts IDENTIFIERS Japan; *Japanese Art ABSTRACT This packet, written for teachers of sixth-grade art and language arts courses, is designed to inspire creative expression in words and images through an appreciation for Japanese art. The selection of paintings presented are from the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution. The interdisCiplinary approach, combines art and language arts. Lessons may be presented independently or together as a unit. Six images of art are provided as prints, slides, and in black and white photographic reproductions. Handouts for student use and a teacher's lesson guide also are included. Lessons begin with an anticipatory set designed to help students begin thinking about issues that will be discussed. A motivational activity, a development section, clusure, and follow-up activities are given for each lesson. Background information is provided at the end of each lesson. -

Protective Armor Engineering Design

PROTECTIVE ARMOR ENGINEERING DESIGN PROTECTIVE ARMOR ENGINEERING DESIGN Magdi El Messiry Apple Academic Press Inc. Apple Academic Press Inc. 3333 Mistwell Crescent 1265 Goldenrod Circle NE Oakville, ON L6L 0A2 Palm Bay, Florida 32905 Canada USA USA © 2020 by Apple Academic Press, Inc. Exclusive worldwide distribution by CRC Press, a member of Taylor & Francis Group No claim to original U.S. Government works International Standard Book Number-13: 978-1-77188-787-8 (Hardcover) International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-42905-723-6 (eBook) All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electric, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and re- cording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publish- er or its distributor, except in the case of brief excerpts or quotations for use in reviews or critical articles. This book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. Reprinted material is quoted with permission and sources are indicated. Copyright for individual articles remains with the authors as indicated. A wide variety of references are listed. Reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable data and information, but the authors, editors, and the publisher cannot assume responsibility for the validity of all materials or the consequences of their use. The authors, editors, and the publisher have attempted to trace the copyright holders of all material reproduced in this publication and apologize to copyright holders if permission to publish in this form has not been obtained. -

1 the Alternate Path: Martial 3

The Alternate Path: Martial 3 Credits -PRODUCER- SCOTT GLADSTEIN -DESIGNERS- SCOTT GLADSTEIN AND IAN SISSON -EDITORS- IAN SISSON AND BRYNN PETANO -ART- JORGE ZAPATA, FERNANDO CORREA, DAVID REVOY, JUSTIN NICHOL, RICK HERSHEY, ANDREW “VIKING” BORTNIAK, MOHAMMED AGBADI, TONY MOW, STORN COOK, FELIPE MOREIRA, GARY DUPUIS, IGNATIUS ANTONI T, SANTIAGO IBORRA (VIA WTACTICS), ALEXANDER (THIRTEENTHAUTUMN), “LUNSTREAM”, “LEKSA”, “KILLY ONE”, “WARPAINTCOBRA”, “BUSONE”, “DOMINICK” -GRAPHIC DESIGN/LAYOUT- SCOTT GLADSTEIN Compatibility with the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game requires the Pathfinder A Product of Little Red Goblin Games, LLC Roleplaying Game from Paizo Publishing, LLC. See http://paizo.com/pathfinderRPG Questions? Comments? Contact us at: for more information on the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game. Paizo Publishing, LLC [email protected] does not guarantee compatibility, and does not endorse this product. http://littleredgoblingames.com/ © 2018, All Rights Reserved OGL Compatible: Open Game License v 1.0a Copyright 2000, Wizards of the Coast, Inc. System Reference Document. Copyright 2000, Wizards of the Coast, Inc.; Authors Jonathan Tweet, Monte Cook, Skip Williams, based on material by E. Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson. PathfinderSample RPG Core Rulebook. Copyright 2009, Paizo Publishing, LLC; Author: Jason Bulmahn, based on material by Jonathan fileTweet, Monte Cook, and Skip Williams. Pathfinder is a registered trademark of Paizo Publishing, LLC, and the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game and the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game Compatibility Logo are trademarks of Paizo Publishing, LLC, and are used under the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game Compatibility License. See http://paizo.com/pathfinderRPG/compatibility for more information on the compatibility license 1 Chapter 0: Introduction What is This Book? EXPANDED MARTIAL CHARACTERS This book is designed for experienced players and Historically the fighter has been the class people presents alternate rules and classes that are more use to wholesale define professional fighters. -

Il Samurai. Da Guerriero a Icona

Il fiume di parole e d’immagini sul Giappone che si riversò a icona Da guerriero Il samurai. in Occidente dopo il 1860 lo configurò per sempre come l’idillica terra del Monte Fuji, coi laghi sereni punteggiati di vele, le geisha in pose seminude e gli indomabili samurai dalle misteriose armature. Il fascino che i guerrieri giapponesi e la loro filosofia di vita esercitarono sulla cultura del Novecento fu pari soltanto al desiderio di conoscere meglio la loro storia e i loro costumi, per svelare i segreti di una casta che prima Il samurai. di sconfiggere il nemico in battaglia aveva deciso, senza rinunciare ai piaceri della vita, di educare il corpo e la mente Da guerriero a icona a sconfiggere i propri limiti e le proprie paure, per raggiungere l’impalpabile essenza delle cose. a cura di Moira Luraschi 10 10 Antropunti Collana diretta da Francesco Paolo Campione Christian Kaufmann Antropunti € 32,00 Collana diretta da Francesco Paolo Campione Il samurai. Christian Kaufmann Da guerriero a icona La Collezione Morigi e altre recenti acquisizioni del MUSEC a cura di Antropunti Moira Luraschi 10 Sommario Note di trascrizione Prefazione 6 e altre avvertenze per la lettura Roberto Badaracco La trascrizione delle parole giapponesi Per la lettura delle parole trascritte ci si ba- segue il Sistema Hepburn modificato, fa- serà sulla fonologia italiana per le vocali, su Saggi I samurai. Guerrieri, politici, intellettuali 11 cendo eccezione per quei pochi casi in cui quella inglese per le consonanti. Si tenga Moira Luraschi un nome è entrato nell’uso corrente in una dunque presente che: ch è la c semiocclu- forma diversa (es. -

Cover Page the Handle Holds

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/42750 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Verberk, B.J.M. Title: De gemaskerde krijger : de menpō in de 16e en 17e eeuw Issue Date: 2016-09-06 Alfabetische woordenlijst 385 A Agemaki 11.11 Agemakitsuke no kan 11.12 Ago-hige 3.18 Asanuno / mafu 12.05 Ase nagashi no ana 3.28 Ase nagashi no kuda 3.37 Aya 12.06 B Bijobō 3.10 Bishamongote 6.03 Byō 10.28 C Chikaragawa 10.38 Chirimen 12.11 Chūsode 5.02 D Dangaedō / dangawaridō 4.04 Dansen’osame / tenuguïtsuke no kan 11.15 Dō 1.09 Dōmaru 1.04 Donsu 12.01 E Edagikumon 11.34 Egawa 11.39 Emi sōmen 3.19 Erimawashi / erimawari 4.12 Etchūbō 3.40 Etchūhaidate 7.06 F Fukikaeshi 2.22 Fukubegote 6.08 386 Fukurin 11.20 Fungomi 7.08 Fusegumi / fusenuï 11.37 G Gaku no ita 6.15 Gattari 4.22 Ginran 12.08 Gosei-akagawa 11.44 Gumi 10.34 Gusokubitsu 9.10 H Hagi-ita 10.27 Haidate 1.12 Hanagarami 10.20 Hana 3.29 Hanbō 3.07 Haraidate 2.17 Haraidatedai 2.18 Haramaki 1.05 Hassōbyō 11.25 Hassōza / iri-hassōza 11.24 Hatsumuri / happuri 3.04 Hawasenuï / hawase-ito 10.39 Hibiki no ana 2.24 Hijigane 6.13 Hikiagejime 7.09 Hikiawase no o 4.16 Hirafukube 6.09 Hiraguke 10.40 Hishinuï no ita 10.02 Hishinuï 10.18 Hishitoji 10.19 Hito-egiku 11.28 Hōate 3.05 Honkozane / kozane 10.06 387 Hoshi 2.09 Hoshikabuto 2.02 I Ichi no ita ; ni no ita enz. -

The Samurai Armour Glossary

The Samurai Armour Glossary Ian Bottomley & David Thatcher The Samurai Armour Glossary www.nihon-no-katchu.com The Samurai Armour Glossary Nihon-No-Katchu.com Open Library Contributors Ian Bottomley & David Thatcher Editor Tracy Harvey Nihon No Katchu Copyright © January 2013 Ian Bottomley and David Thatcher. This document and all contents. This document and images may be freely shared as part of the Nihon-No-Katchu Open Library providing that it is distributed true to its original format. Illustrations by David Thatcher 2 The Samurai Armour Glossary www.nihon-no-katchu.com This glossary has been compiled for students of Japanese Armour. Unlike conventional glossaries, this text has been divided into two versions. The first section features terminology by armour component, the second is indexed in alphabetical order. We hope you will enjoy using this valuable resource. Ian & Dave A Namban gusoku with tameshi Edo-Jindai 3 The Samurai Armour Glossary www.nihon-no-katchu.com Contents Armour Makers! 6 Armour for the Limbs! 7 Body Armour! 9 Facial Armour! 16 Helmets! 21 Neck Armour! 28 Applied Decoration! 29 Chain Mail! 30 General Features! 31 Lacing! 32 Materials! 33 Rivets & Hinges! 34 Clothing! 35 Colours! 36 Crests! 36 Historic Periods! 37 Sundry Items! 37 Alphabetical Index! 38 4 The Samurai Armour Glossary www.nihon-no-katchu.com Armour Kabuto Mengu Do Kote Gessan Haidate Suneate A Nuinobe-do gusoku with kawari kabuto Edo-Jindai 5 The Samurai Armour Glossary www.nihon-no-katchu.com Armour Makers Bamen - A small but respected group of armourers that worked during the Muromachi period until the 1700s. -

Lexique Des Termes Japonais Utilises Pour Les Sabres Et Les Armures

LEXIQUE DES TERMES JAPONAIS UTILISES POUR LES SABRES ET LES ARMURES ABARA DO : Cuirasse imitant un torse humain squelettique évoquant le Bouddha. ABUMI : Étrier ABUMI ZURI NO KAWA : Pièce de cuir à la partie inféro interne d’une jambière afin de ne pas user le cuir de l’étrier avec du métal. AGEMAKI : Nœud de passementerie décoratif fixé à un anneau au dos des armures O YOROI, et où s‘attachent les cordons postérieurs des épaulières (SODE). AGEMAKI NO KAN : Anneau d’attache de l’AGEMAKI. AGO NO O BENRI : Boucle fixée au MENPO pour y solidariser les cordons d’attache du casque. AIBIKI : Système d’attachement reliant les bretelles de l’armure à la partie antérieure de la cuirasse. Nom utilisé pour les armures dites « modernes » (TOSEI GUSOKU). AIKUCHI : «bouches unies» Poignard sans garde. AKABE YOROI : « armure de cou » Gorgerin protégeant le cou dans les armures anciennes de type TANKO. AKA GANE : «métal rouge» Cuivre (synonyme DO). AKA KIN : Alliage d’or et de cuivre utilisé pour la décoration des TSUBA, entre autres. AKODA NARI : Forme de casque évoquant un brûle parfum ou un melon. AMAOI : Renforts métalliques longitudinaux à l’extrémité du fourreau d’un TACHI. Synonyme de SHIBA HIKI. AMIDA YASUR I : Lignes sculptées dans le métal d'une tsuba irradiant depuis le centre. ANA : Orifice. AOI : Décoration en forme de fleur de mauve Japonaise, souvent utilisée comme MON. AOIBA ZA : Plaque métallique entourant l’orifice au sommet (TEHEN) des casques du début de l’ère HEIAN. AOIGATA : TSUBA en forme de AOI. AO KIN : Alliage d’or et d’argent utilisé pour la décoration des TSUBA, entre autres. -

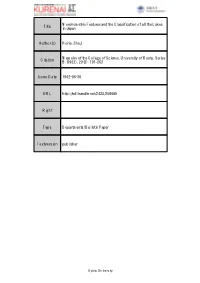

Title Morphometric Features and the Classification of All the Lakes In

Morphometric Features and the Classification of all the Lakes Title in Japan Author(s) Horie, Shoji Memoirs of the College of Science, University of Kyoto. Series Citation B (1962), 29(3): 191-262 Issue Date 1962-06-30 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/258665 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University MEMOIRS OF THE COLLEGE OI? SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY oF 1<YOTO, SERIES B, Vol. XXIX, No. 3, Article 2 (Biology), 1962 Morphome'tric Features and the Classification of all the Lal<es in Japan By Sh6ji HoRIE Otsu Hydrobio}ogical Station, Universi.ty of Kyoto (Osbom Zoological Laboratory, Yale ILJniversity) (Received MarÅëh 20, 1962) !ntroduetien The Japanese IslaRds which consist of four main parts, narnely Hol<kaido, Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu, stretck from approximately 460N to 240N along tke easterR margin of the Ellrasiatic continent. Geologically speaking, this part of the globe is on.e of typically unstable crust, hence the Japanese often ex- perience severe earthquakes. Besides, the western part of the Peri-Pacific Volcanic Zone runs from the KamÅëhatka Peninsula via the Kuriles, Hokkaido, Honsltu, Kyushu, Ryukyu and to the Phillipine Is}ands. Both the presence of the eartltquake zone and severe vulcanism, together with the steep slopes of the mountains wkich occupy almost all of the country, have resulted in many lakes and ponds in the Japanese Islands. The total numbey of them is about 600 ln this small in.".u}ar country, which is almost equal in area to the State Montana of the United States. They are, moreover, not only numerous but sorae are very important Iakes from the viewpoint of both limnology and geology. -

OFFENBACH 2012 POSTPRINTS of the 10Th Interim Meeting

OFFENBACH ICOM OFFENBACH - CC LEATHER & RELATED August 29 2012 - 31, 2012 ICOM-CC LEATHER & RELATED MATERIALS WORKING GROUP POSTPRINTS MATERIALS WORKING GR of the 10th Interim Meeting OUP EDITED BY CÉLINE BONNOT-DICONNE, CAROLE DIGNARD AND JUTTA GÖPFRICH ICOM-CC Leather and Related Materials WG Offenbach 2012 2 ICOM-CC Leather and Related Materials WG Offenbach 2012 POSTPRINTS of the 10th Interim Meeting of the ICOM-CC Leather & Related Materials Working Group Offenbach, Germany 2012 ACTES de la 10ème Réunion Intermédiaire du Groupe de Travail Cuir et Matériaux Associés de l’ICOM-CC Offenbach, Allemagne 2012 Edited by/ Sous la direction de Céline Bonnot-Diconne (2CRC), Carole Dignard (Canadian Conservation Institute / Institut Canadien de Conservation), Jutta Göpfrich (Deutsches Ledermuseum Schuhmuseum). 3 ICOM-CC Leather and Related Materials WG Offenbach 2012 4 ICOM-CC Leather and Related Materials WG Offenbach 2012 Organizing committee / Comité d’organisation Villa Médicis, Rome, Italy and 2CRC, Moirans, Céline Bonnot-Diconne France Carole Dignard ICC/CCI, Ottawa, Canada Nina Frankenhauser Offenbach, Germany Jutta Göpfrich Offenbach, Germany Editorial Committee / Comité de lecture Céline Bonnot-Diconne 2CRC, Moirans, France Carole Dignard ICC/CCI, Ottawa, Canada Theo Sturge Northampton, United-Kingdom Acknowledgments / Remerciements - ICOM Germany, Dr. Klaus Weschenfelder (President) - DLM- Deutsches Ledermuseum/ Schuhmuseum Offenbach - Académie de France à Rome, Villa Médicis (Eric de Chassey, Annick Lemoine). - Canadian Conservation Institute/Institut canadien de conservation These Postprints have been supported by Hermès. Cette publication a bénéficié du soutien de la Maison Hermès. © ICOM-CC March 2013 ISBN 978-3-9815440-1-5 To order this book, please contact: DLM- Deutsches Ledermuseum/ Schuhmuseum Offenbach Frankfurter Strasse 86 D-63067 Offenbach, Germany T. -

A Sengoku Jidai Fantasy

A Sengoku Jidai Fantasy 1 Table of Contents The Empire of Yakkaida . Page 3 Races . Page 4 Equipment . Page 19 Materials and Quality . Page 23 Feats . Page 26 Background and Honor . Page 27 Faith . Page 29 The Clans of Yakkaida . Page 33 The Continent . Page 35 The Map . Page 38 2 It is the Yakkaidan Year 1450. Almost a millennium and a half have passed since the first Emperor, Wei, took the Gold Lotus Throne. Since then, the power of the Emperor has risen and fallen with the ages. Fifty years ago, the Emperor Keishi died with two sons, but neither one selected to succeed. The two sons each claimed the throne for himself, and the Divine Mandate was uncertain. Prince Fuji was the elder son by a matter of minutes, though he was disliked for his tempestuous nature by many. Prince Yabu was second-born, but was well-liked by many, and made friends easily. Before the Samurai Lords of the Nakamura Bakufu could decide the issue, the Yunnic Khan of the Jade Empire came across the sea to conquer and subjugate the islands. Midoriko and Aizushima were occupied, and the Daimyo rode to war without deciding the case of the Imperial Throne. In the war itself, Yabu fell to a Yun assassin’s blade, while Fuji showed poor leadership, even abandoning his capital, nominally to set up a secure base in Enishima, during its time of greatest need. With the end of the war, the Yun were sent back to the continent, but the lands of Yakkaida were broken. -

Player's Handbook

Doorknobs & Derring-do Player's Handbook - Rules & Playing The Game Adventuring Items & Weapons Magic Spells (d1 & ! Traditions" Prayers & Po#ers $limbing - &oor'no%s & &erring-do (codename Sourdough Tea) is a %oo' o) rules )or role-playing a science )antasy medieval picares*ue+ ,re#ed #ith lots o) sunlight in a glass -ar #ith %its o) sourdough. old pieces o) paper copied )rom the %est. //0 1verything )rom 2ayra3s GR4G. !/0 o) ta%les )rom ,en Milton3s Knave. 660 Phlo73s 8uests. Prayers. etc+. 190 o) Animal Races )rom G:4G; Many Rats on A Stic'< ==0 $lasses )rom :air o) The :am%. 9>0 $lasses )rom &eus e7 Para%ola. Squig%oss. and 4SR &iscorrd community at large. 10 o) the Edition-That(Must(?ot(,e(?amed. and copies o) and various Goblin Laws of Gaming 11.13.20 Edition gathered %y $astle :ibrarian Skills B Languages# 8ou ha&e one skill, plus one for each Rules & Playing The Game point of INT (if positive)" Skills are just a word that describes something a 6+ knows how to do. 5here are no specific rules for using them. If a roll is re uired as a test of How to Roll your skills, add highest ,bility 1core you can justify plus If you attempt something where the outcome is risky or your le&el" difficult to describe, you make a “roll”, which means rolling a d20 e ual to or greater than a number, known as Difficulty" In this game, there are three difficulty classes# 12 E6 & Ce&els (a&erage), 18 %difficult), and 24 (heroic). -

The Book of Mystical Materials

1 The Beyond Heroes Roleplaying Game Book XXXIV: The Book of Mystical Materials Writing and Design: Marco Ferraro The Book of Mystical Materials Copyright © 2021 Marco Ferraro All Rights Reserved This is meant as a free, amateur, fan production. Absolutely no money is generated from it. Wizards of the Coast, Dungeons & Dragons, Dark Sun and their logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast LLC in the United States and other countries. © 2021 Wizards. All Rights Reserved. Beyond Heroes is not affiliated with, endorsed, sponsored, or specifically approved by Wizards of the Coast LLC. Contents Foreword 3 Magical Materials 4 Future Materials 21 Normal Materials 24 Materials from the DC Universe 26 Materials from the Marvel Universe 34 Materials from the Rolemaster Universe 42 Materials from the Palladium Universe 47 Materials from the Star Trek Universe 48 Materials from the Warhammer Universe 50 Materials from the Dr Who Universe 54 Materials from Other Universes 55 Materials Costs 67 Armour Materials Tables 72 Weapon Materials Tables 76 Magic Item Creation 79 Classes 81 2 Foreword The Beyond Heroes Role Playing Game is based on a heavily revised derivative version of the rules system from Advanced Dungeons and Dragons 2nd edition. It also makes extensive use of the optional point buying system as presented in the AD&D Player’s Option Skills and Powers book. My primary goal was to make this system usable in any setting, from fantasy to pulp to superhero to science fiction. Mystical substances are legendary substances from a relatively cohesive set of myths. In real life, a metal is an element of the periodic table which belongs to one of certain groups/columns and has a specific type crystal lattice with free electrons.