Paganini's 'Il Cannone'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B&F Magazine Issue 31

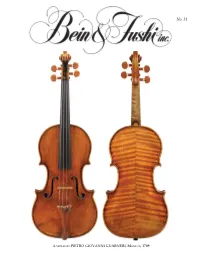

No. 31 A VIOLIN BY PIETRO GIOVANNI GUARNERI, MANTUA, 1709 superb instruments loaned to them by the Arrisons, gave spectacular performances and received standing ovations. Our profound thanks go to Karen and Clement Arrison for their dedication to preserving our classical music traditions and helping rising stars launch their careers over many years. Our feature is on page 11. Violinist William Hagen Wins Third Prize at the Queen Elisabeth International Dear Friends, Competition With a very productive summer coming to a close, I am Bravo to Bein & Fushi customer delighted to be able to tell you about a few of our recent and dear friend William Hagen for notable sales. The exquisite “Posselt, Philipp” Giuseppe being awarded third prize at the Guarneri del Gesù of 1732 is one of very few instruments Queen Elisabeth Competition in named after women: American virtuoso Ruth Posselt (1911- Belgium. He is the highest ranking 2007) and amateur violinist Renee Philipp of Rotterdam, American winner since 1980. who acquired the violin in 1918. And exceptional violins by Hagen was the second prize winner Camillo Camilli and Santo Serafin along with a marvelous of the Fritz Kreisler International viola bow by Dominique Peccatte are now in the very gifted Music Competition in 2014. He has hands of discerning artists. I am so proud of our sales staff’s Photo: Richard Busath attended the Colburn School where amazing ability to help musicians find their ideal match in an he studied with Robert Lipsett and Juilliardilli d wherehh he was instrument or bow. a student of Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho. -

A Violin by Giuseppe Giovanni Battista Guarneri

141 A VIOLIN BY GIUSEPPE GIOVANNI BATTISTA GUARNERI Roger Hargrave, who has also researched and drawn the enclosed poster, discusses an outstanding example of the work of a member of the Guarneri family known as `Joseph Guarneri filius Andrea'. Andrea Guarneri was the first He may never have many details of instruments by of the Guarneri family of violin reached the heights of his Joseph filius at this period recall makers and an apprentice of contemporary, the Amati school, this type of Nicola Amati (he was actually varnish, in combination with registered as living in the house Antonio Stradivarius, but he the freer hand of Joseph, gives of Nicola Amati in 1641). Andrea's does rank as one of the the instruments a visual impact youngest son, whose work is il - greatest makers of all time. never achieved by an Amati or , lustrated here, was called. We should not forget he with the exception of Stradi - Giuseppe. Because several of the sired and trained the great vari, by any other classical Guarneri family bear the same del Gesu' maker before this time. christian names, individuals have traditionally been identified by a It should be said, however, suffix attached to their names. that the varnish of Joseph filius Thus, Giuseppe's brother is known as `Peter Guarneri varies considerably. It is not always of such out - of Mantua' to distinguish him from Giuseppe's son, standing quality the same can be said of Joseph's pro - who is known as `Peter Guarneri of Venice'. duction in general. If I were asked to describe the instruments of a few of the great Cremonese makers Giuseppe himself is called 'Giuseppe Guarneri filius in a single word, I would say that Amatis (all of them) Andrea' or, more simply, `Joseph filius' to distinguish are `refined', Stradivaris are `stately', del Gesus are him from his other son, the illustrious 'Giuseppe `rebellious' and the instruments of Joseph filius An - Guarneri del Gesu'. -

Die Sammlung Historischer Streichinstrumente Der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank

OESTERREICHISCHE NATIONALBANK EUROSYSTEM Die Sammlung historischer Streichinstrumente der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank The collection of Historical String Instruments of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank Inhaltsverzeichnis Contents Impressum Medieninhaberin: Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Otto-Wagner-Platz 3, 1090 Wien, T: (+43 1) 404 20-6605, F: (+43 1) 404 20-6697, www.oenb.at Redaktion: Mag. Brigitte Alizadeh-Gruber, Muna Kadum, Martina Leitner, Mag. Irene Mühldorf Grafik, Layout und Satz: Melanie Schuhmacher Fotos: © Graphisches Atelier Neumann, Wien Druck: Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Abteilung für Öffentlichkeitsarbeit und Publikationen, Gruppe Multimedia-, Internet- und Print-Service. © Oesterreichische Nationalbank, 2013. Streichinstrumente/ String Instruments 9 Amati Andrea 10 Violoncello, Cremona, spätes 16. Jh. 10 Bergonzi Carlo 12 Violine, Cremona 1723 12 Violine, Cremona nach 1724 14 Bergonzi Michelangelo 16 Violine, Cremona um 1740 16 Violine, „ex Hamma-Segelman“, Cremona um 1750 18 Camilli Camillus 20 Violine, Mantua 1736 20 Ceruti Giovanni Battista 22 Viola, Cremona um 1810 22 Gagliano Alessandro 24 Violoncello, Neapel ca. 1710 24 Grancino Giovanni 26 Violoncello, „ex Piatti“ – „ex Dunlop“, Mailand 1706 26 Guadagnini Giovanni Battista 28 Violoncello, „ex von Zweygberg“, Piacenza 174. 28 Violine, Mailand 1749 30 Violine, „ex Meinel“, Turin um 1770–1775 32 Violine, Turin 1772 34 Violine, „Mantegazza“, Turin 1774 36 Violine, Turin 177. 38 Viola, Turin 1784 40 Guarneri Andrea 42 Violine, Cremona, Mitte 17. Jh. 42 Guarneri del Gesù Giuseppe 44 Violine, „ex Sorkin“, Cremona 1731 44 Violine, „ex Guilet“, Cremona nach 1732 46 Violine, „ex Carrodus“, Cremona 1741 48 Lorenzini Gaspare 50 Violine, Piacenza um 1760 50 Maggini Giovanni Paolo 52 Viola, Brescia, frühes 17. Jh. 52 Montagnana Domenico 54 Violine, Venedig 1727 54 Seraphin Sanctus 56 Violine, Venedig 1733 56 Violine, „ex Hamma“, Venedig nach 1748 58 Silvestre Pierre 60 Violine, „ex Moser“, Lyon ca. -

Reconstructing Lost Instruments Praetorius’S Syntagma Musicum and the Violin Family C

Prejeto / received: 3. 5. 2019. Odobreno / accepted: 12. 9. 2019. doi: 10.3986/dmd15.1-2.07 RECONSTRUCTING LOST INSTRUMENTS Praetorius’S Syntagma musicum and the Violin Family C. 1619 Matthew Zeller Duke University Izvleček: Knjigi De organographia in Theatrum Abstract: Michael Praetorius’s De organographia instrumentorum Michaela Praetoriusa vsebujeta and Theatrum instrumentorum provide valuable dragocene namige, ki pomagajo pri poznavanju clues that contribute to a new understanding glasbil iz družine violin okoli leta 1619; številna of the violin family c. 1619, many surviving ex- preživela glasbila so manjša, kot so bili izvirniki amples of which are reduced in size from their v 16. in 17. stoletju. Podatki o preživelih glas- sixteenth- and seventeenth-century dimensions. bilih – predvsem izdelki družine Amati – skupaj The record of surviving instruments – especially z metrologijo, sekundarno dokumentacijo in those of the Amati family – alongside metrologic, ikonografskim gradivom kažejo na to, da je documentary and iconographic evidence shows Michael Praetorius opisal veliko glasbilo, po that Michael Praetorius describes a large in- velikosti izjemno podobno violončelu (basso strument conforming remarkably well to the da braccio),kar je odličen primer predstavitve original dimensions of the basso da braccio glasbila iz družine violin in točne uglasitve, kot (violoncello), as well as furnishing an excellent so jih poznali v času izida Praetoriusovega dela. scale representation of the violin family as it was at the time of these works’ -

The Working Methods of Guarneri Del Gesů and Their Influence Upon His

45 The Working Methods of Guarneri del Gesù and their Influence upon his Stylistic Development Text and Illustrations by Roger Graham Hargrave Please take time to read this warning! Although the greatest care has been taken while compiling this site it almost certainly contains many mistakes. As such its contents should be treated with extreme caution. Neither I nor my fellow contributors can accept responsibility for any losses resulting from information or opin - ions, new or old, which are reproduced here. Some of the ideas and information have already been superseded by subsequent research and de - velopment. (I have attempted to included a bibliography for further information on such pieces) In spite of this I believe that these articles are still of considerable use. For copyright or other practical reasons it has not been possible to reproduce all the illustrations. I have included the text for the series of posters that I created for the Strad magazine. While these posters are all still available, with one exception, they have been reproduced without the original accompanying text. The Labels mentions an early form of Del Gesù label, 98 later re - jected by the Hills as spurious. 99 The strongest evi - Before closing the body of the instrument, Del dence for its existence is found in the earlier Gesù fixed his label on the inside of the back, beneath notebooks of Count Cozio Di Salabue, who mentions the bass soundhole and roughly parallel to the centre four violins by the younger Giuseppe, all labelled and line. The labels which remain in their original posi - dated, from the period 1727 to 1730. -

The Strad Magazine

FRESH THINKING WOOD DENSITOMETRY MATERIAL Were the old Cremonese luthiers really using better woods than those available to other makers FACTS in Europe? TERRY BORMAN and BEREND STOEL present a study of density that seems to suggest otherwise Violins await testing on a CT scanner gantry S ALL LUTHIERS ARE WELL AWARE, of Stradivari. To test this conjecture, we set out to compare the business of making an instrument of the the wood employed by the classical Cremonese makers with violin family is fraught with pitfalls. There that used by other makers, during the same time period but are countless ways to ruin the sound of the from various regions across Europe. This would eliminate one fi nished product, starting with possibly the variable – the ageing of the wood – and allow the tracking of Amost fundamental decision of all: what wood to use. In the past geographical and topographical variation. In particular, we 35 years we have seen our knowledge of the available options wanted to investigate the densities of the woods involved, which expand greatly – and as we learn more about the different wood we felt could be the key to unlocking these secrets. choices, it is increasingly hard not to agonise over the decision. What are the characteristics we need as makers? Should we just WHY DENSITY? look for a specifi c grain line spacing, or a good split? Those were The three key properties of wood, from an instrument maker’s the characteristics that makers were once taught to watch out perspective, are density, stiffness (‘Young’s modulus’) and for, and yet results are diffi cult to repeat from instrument to damping (in its simplest terms, a measure of how long an object instrument when using the same pattern – suggesting these are will vibrate after being set in motion). -

Searching for Giuseppe Guarneri Del Gesù: a Paper-Chase and a Proposition

Searching for Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù: a paper-chase and a proposition Nicholas Sackman © 2021 During the past 200 years various investigators have laboured to unravel the strands of confusion which have surrounded the identity and life-story of the violin maker known as Bartolomeo Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù. Early-nineteenth-century commentators – Count Cozio di Salabue, for example – struggled to make sense of the situation through the physical evidence of the instruments they owned, the instruments’ internal labels, and the ‘understanding’ of contemporary restorers, dealers, and players; regrettably, misinformation was often passed from one writer to another, sometimes acquiring elaborations on the way. When research began into Cremonese archives the identity of individuals (together with their dates of birth and death) were sometimes announced as having been securely determined only for subsequent investigations to show that this certainty was illusory, the situation being further complicated by the Italian habit of christening a new- born son with multiple given names (frequently repeating those already given to close relatives) and then one or more of the given names apparently being unused during that new-born’s lifetime. During the early twentieth century misunderstandings were still frequent, and even today uncertainties still remain, with aspects of del Gesù’s chronology rendered opaque through contradictory or no documentation. The following account examines the documentary and physical evidence. ***** NB: During the first decades of the nineteenth century there existed violins with internal labels showing dates from the 1720s and the inscription Joseph Guarnerius Andrea Nepos. The Latin Dictionary compiled by Charlton T Lewis and Charles Short provides copious citations drawn from Classical Latin (as written and spoken during the period when the Roman Empire was at its peak, i.e. -

The History of the King Violincello Created by Andrea Amati(1505-1577)

May 2011 Volume 3 Magazine for Strings The History of The King Violincello created by Andrea Amati(1505-1577) YoYo Ma: Forging a Career in Music The Art of the Luthier The Music of Mozart, Become Inspired! The History of The King Violincello 2-10 created by Andrea Amati (1505-1577) Peggy Connor Forging a Career in Music 11-30 Inspiring advice from Yo Yo Ma The Art of the Luthier 31-35 Features A delicate art Harold Golden The Music of Mozart 36-45 Be inspired! Thomas Smith The Newest Juilllard Prodigy 46-57 Meet an amazing violinist Peggy Connor Priceless Violins of Cremona, Italy 58-63 A tour of the Museum of Cremona John Davis Suzuki Students 64-72 Observe how they learn Harold Golden Chicago Symphony Cellists 73-84 The newest generation John Davis The Latest Trends in the Music 85-94 A discussion with contemporary composers Eliza Jones Identifying a Young Prodigy 95-101 What defines truly gifted? Thomas Smith Orchestral Performance Schedules 102-105 May-Sept. Employment Opportunities 106-110 May 2011 May 2011 1 The History of The King Violincello Giuseppe (del Gesu) (1698-1744), Antonio Stradivari (1644-1737) Created by Andrea Amati, 1505-1577, Cremona, Italy of Cremona- and two of his sons, By Peggy Connor Francesco Stradivari (1671-1743) Omobono Stradivari (1679-1742), Jacob Stainer(1617-1683) of Absom The violin emerged from northern Italy Amati instruments that have survived. in Tyrol in the early 16th century, preceeded and One of oldest “surviving” dated violin, is Documented resident apprentices of the evolving from three likely fretted and non the “Charles IX” by Andrea Amati, made in Nicolo Amati workshop: fretted, stringed instruments: the rebec, the Cremona in1560. -

1002775354-Alcorn.Pdf

3119 A STUDY OF STYLE AND INFLUENCE IN THE EARLY SCHOOLS OF VIOLIN MAKING CIRCA 1540 TO CIRCA 1800 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Allison A. Alcorn, B.Mus. Denton, Texas December, 1987 Alcorn, Allison A., A Study of Style and Influence in the Ear School of Violin Making circa 1540 to circa 1800. Master of Music (Musicology), December 1987, 172 pp., 2 tables, 31 figures, bibliography, 52 titles. Chapter I of this thesis details contemporary historical views on the origins of the violin and its terminology. Chapters II through VI study the methodologies of makers from Italy, the Germanic Countries, the Low Countries, France, and England, and highlights the aspects of these methodologies that show influence from one maker to another. Chapter VII deals with matters of imitation, copying, violin forgery and the differences between these categories. Chapter VIII presents a discussion of the manner in which various violin experts identify the maker of a violin. It briefly discusses a new movement that questions the current methods of authenti- cation, proposing that the dual role of "expert/dealer" does not lend itself to sufficient objectivity. The conclusion suggests that dealers, experts, curators, and musicologists alike must return to placing the first emphasis on the tra- dition of the craft rather than on the individual maker. o Copyright by Allison A. Alcorn TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES.... ............. ........viii LIST OF TABLES. ................ ... x Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . .............. *.. 1 Problems in Descriptive Terminology 3 The Origin of the Violin....... -

Almanacco 2003

2003 5-07-2004 12:05 Pagina 1 2003 5-07-2004 12:05 Pagina 2 2003 5-07-2004 12:05 Pagina 3 almanacco della presenza veneziana nel mondo almanac of the venetian presence in the world fondazione venezia 2000 Ma r s i l i o 2003 5-07-2004 12:05 Pagina 4 a cura di/edited by Fabio Isman hanno collaborato/texts by Sandro Cappelletto Giuseppe De Rita Ketty Gottardo Rosella Lauber Stefania Mason Marino Zorzi si ringraziano/many thanks to Bernard Aikema Linda Borean Andrea De Marchi Andrea Emiliani Augusto Gentili Olimpia Marini Clarelli Gioia Mori Giovanna Nepi Sciré Francesca Paterlongo Francesca Pitacco Giandomenico Romanelli in collaborazione con Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Venezia in collaboration with traduzione inglese Olga Barmine English translation progetto grafico/layout Studio Tapiro, Venezia © 2003 Marsilio Editori® s.p.a. in Venezia isbn 88-317-8393-9 www.marsilioeditori.it In copertina: Giorgio o Zorzi da Caste lfranco, detto Gior gione, e T iziano Vecellio, V enere dorm iente (dettaglio), Dresda, Gemälde galerie. Il dipinto è seg nalato nel 1 525 da Marca n t o n i o Michiel in cas a del patrizio Gerolamo Mar cello, a S an T omà; ne l 1699 il mer cante L e Roy lo acq uista a V enezia per Au gusto i i di Sass onia. Front cover: Giorgio or Zorzi da Castelfranco, known as Giorgione, and Tiziano Vecellio, Sleeping Venus (detail), Dresden, Gemäldegalerie. The drawing was documented in 1525 by Marcantonio Michiel in the home of patrician Gerolamo Marcello at San Tomà; in 1699, it was purchased in Venice by the merchant Le Roy for Augustus ii of Saxony. -

Paganini's Violin

Il Cannone FRANCESCA DEGO plays Paganini’s Violin Francesca Leonardi piano Nicolò Paganini, 1820 Paganini, Nicolò Drawing courtesy of Associazione Amici di Paganini Il Cannone – Francesca Dego Plays Paganini’s Violin Nicolò Paganini (1782 – 1840) 1 La Clochette (1826)* 6:35 (La campanella) Rondo Finale from Concerto No. 2 in B minor, Op. 7 for Violin and Orchestra Arranged c. 1905 for Violin and Piano by Fritz Kreisler Frau Marie Rosselt in Dankbarkeit und Verehrung gewidmet Allegretto grazioso – Meno mosso – Tempo I – Meno mosso Tempo I – Molto moderato – Meno mosso – Più mosso Fritz Kreisler (1875 – 1962) Recitativo und Scherzo-Caprice, Op. 6 (c. 1911) 4:33 for Solo Violin À Eugène Ysaÿe, le maître et l’ami 2 Recitativo. Lento con espressione – Tranquillo – 2:32 3 Scherzo. Presto e brillante – Pesante – Energico – Pesante 2:00 3 John Corigliano (b. 1938) 4 The Red Violin Caprices(1997) 8:10 for Solo Violin Edited by Joshua Bell Theme = c. 60 – Variation 1. Presto – Variation 2. Con bravura – Fast and free – Variation 3. Adagio, languid – Variation 4. Slowly con rubato – Faster – Tempo I – Faster – Presto – Slower – Variation 5. Presto, pesante – Presto possibile Carlo Boccadoro (b. 1963) premiere recording 5 Come d’autunno (2019) 4:31 (As in Autumn) for Solo Violin A Francesca Dego ( = 150) – Cantabile, tempo flessibile – Poco più lento – A tempo [Cantabile] – Tempo I – Cantabile – Poco più lento – Tempo I, lontano, come un ricordo – Calmo – Tempo I – [Calmo] 4 Nicolò Paganini premiere recording 6 Cantabile, Op. 17 (1823)* 5:07 in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur • in re maggiore for Violin and Guitar / Piano Piano Accompaniment Arranged 2019 by Carlo Boccadoro A Francesca e Francesca [ ] Gioachino Rossini (1792 – 1868) 7 Un mot à Paganini (c. -

The Working Methods of Guarneri Del Gesů and Their Influence Upon His

9 The Working Methods of Guarneri del Gesù and their Influence upon his Stylistic Development Text and Illustrations by Roger Graham Hargrave Please take time to read this warning! Although the greatest care has been taken while compiling this site it almost certainly contains many mistakes. As such its contents should be treated with extreme caution. Neither I nor my fellow contributors can accept responsibility for any losses resulting from information or opin - ions, new or old, which are reproduced here. Some of the ideas and information have already been superseded by subsequent research and de - velopment. (I have attempted to included a bibliography for further information on such pieces) In spite of this I believe that these articles are still of considerable use. For copyright or other practical reasons it has not been possible to reproduce all the illustrations. I have included the text for the series of posters that I created for the Strad magazine. While these posters are all still available, with one exception, they have been reproduced without the original accompanying text. The Mould and the Rib Structure they were not, in their basic form, the result of any innovative mathematical composition. The elegance and purity of the violin form exer - cises such fascination that it has been the subject of The outline of a violin is only one element of its enquiry for more than two centuries; questions about complex design. It is still not known which was es - its design have generated almost as much interest as tablished first, the mould around which the violin the subject of Cremonese varnish and its composi - was constructed (which represents the chamber of tion.