The Working Methods of Guarneri Del Gesů and Their Influence Upon His

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stowell Make-Up

The Cambridge Companion to the CELLO Robin Stowell Professor of Music, Cardiff University The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 1RP,United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia © Cambridge University Press 1999 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1999 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Adobe Minion 10.75/14 pt, in QuarkXpress™ [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data ISBN 0 521 621011 hardback ISBN 0 521 629284 paperback Contents List of illustrations [page viii] Notes on the contributors [x] Preface [xiii] Acknowledgements [xv] List of abbreviations, fingering and notation [xvi] 21 The cello: origins and evolution John Dilworth [1] 22 The bow: its history and development John Dilworth [28] 23 Cello acoustics Bernard Richardson [37] 24 Masters of the Baroque and Classical eras Margaret Campbell [52] 25 Nineteenth-century virtuosi Margaret Campbell [61] 26 Masters of the twentieth century Margaret Campbell [73] 27 The concerto Robin Stowell and David Wyn Jones [92] 28 The sonata Robin Stowell [116] 29 Other solo repertory Robin Stowell [137] 10 Ensemble music: in the chamber and the orchestra Peter Allsop [160] 11 Technique, style and performing practice to c. -

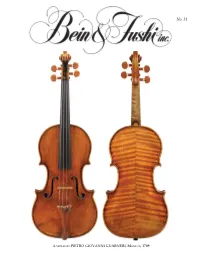

B&F Magazine Issue 31

No. 31 A VIOLIN BY PIETRO GIOVANNI GUARNERI, MANTUA, 1709 superb instruments loaned to them by the Arrisons, gave spectacular performances and received standing ovations. Our profound thanks go to Karen and Clement Arrison for their dedication to preserving our classical music traditions and helping rising stars launch their careers over many years. Our feature is on page 11. Violinist William Hagen Wins Third Prize at the Queen Elisabeth International Dear Friends, Competition With a very productive summer coming to a close, I am Bravo to Bein & Fushi customer delighted to be able to tell you about a few of our recent and dear friend William Hagen for notable sales. The exquisite “Posselt, Philipp” Giuseppe being awarded third prize at the Guarneri del Gesù of 1732 is one of very few instruments Queen Elisabeth Competition in named after women: American virtuoso Ruth Posselt (1911- Belgium. He is the highest ranking 2007) and amateur violinist Renee Philipp of Rotterdam, American winner since 1980. who acquired the violin in 1918. And exceptional violins by Hagen was the second prize winner Camillo Camilli and Santo Serafin along with a marvelous of the Fritz Kreisler International viola bow by Dominique Peccatte are now in the very gifted Music Competition in 2014. He has hands of discerning artists. I am so proud of our sales staff’s Photo: Richard Busath attended the Colburn School where amazing ability to help musicians find their ideal match in an he studied with Robert Lipsett and Juilliardilli d wherehh he was instrument or bow. a student of Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho. -

A Violin by Giuseppe Giovanni Battista Guarneri

141 A VIOLIN BY GIUSEPPE GIOVANNI BATTISTA GUARNERI Roger Hargrave, who has also researched and drawn the enclosed poster, discusses an outstanding example of the work of a member of the Guarneri family known as `Joseph Guarneri filius Andrea'. Andrea Guarneri was the first He may never have many details of instruments by of the Guarneri family of violin reached the heights of his Joseph filius at this period recall makers and an apprentice of contemporary, the Amati school, this type of Nicola Amati (he was actually varnish, in combination with registered as living in the house Antonio Stradivarius, but he the freer hand of Joseph, gives of Nicola Amati in 1641). Andrea's does rank as one of the the instruments a visual impact youngest son, whose work is il - greatest makers of all time. never achieved by an Amati or , lustrated here, was called. We should not forget he with the exception of Stradi - Giuseppe. Because several of the sired and trained the great vari, by any other classical Guarneri family bear the same del Gesu' maker before this time. christian names, individuals have traditionally been identified by a It should be said, however, suffix attached to their names. that the varnish of Joseph filius Thus, Giuseppe's brother is known as `Peter Guarneri varies considerably. It is not always of such out - of Mantua' to distinguish him from Giuseppe's son, standing quality the same can be said of Joseph's pro - who is known as `Peter Guarneri of Venice'. duction in general. If I were asked to describe the instruments of a few of the great Cremonese makers Giuseppe himself is called 'Giuseppe Guarneri filius in a single word, I would say that Amatis (all of them) Andrea' or, more simply, `Joseph filius' to distinguish are `refined', Stradivaris are `stately', del Gesus are him from his other son, the illustrious 'Giuseppe `rebellious' and the instruments of Joseph filius An - Guarneri del Gesu'. -

A Violin by Jacobus Stainer 1679

146 A VIOLIN BY JACOBUS STAINER 1679 Roger Hargrave examines the construction and workmanship of this violin, which still retains its original undisturbed baroque neck. Roger Hargrave se penche sur la construction et la the necessary experience. facon d'un violon Jacobus Stainer, 1679, qui conserve Earlier Füssen in the Allgäu might have been a con - son manche baroque original encore intact. sideration, however, the ravages of the thirty years Roger Hargrave untersucht den Bau and die war had left Füssen bereft of skilled instrument mak - Machart einer Violine von Jacobus Stainer, 1679, ers, most of whom had found refuge in Italy and deren ursprünglicher barocker Hals unversehrt in particular in Venice, Rome and Padua. erhalten ist. Experts seem to agree that Stainer learned Jacobus Stainer is one of the very few non - his trade in Italy. And although this agree - Italian violin makers whose life and work have ment mostly rests on analogies of Stainer's been seriously researched. work, it is also known (from his writings) that he was familiar with the language. Furthermore, There have been a number of important publi - there are several oral traditions relating to an cations, most of which have drawn upon the Italian apprenticeship. As might be expected scholarly research work of the late Professor however these oral traditions are contra - Dr. Walter Senn. However, in spite of dictory, on the one hand saying that Senn's magnificent efforts, several im - Stainer worked in Venice and on the portant questions remain unanswered, other that he worked in Cremona. the exact dates of Stainer's birth and death, whether he used both written and Although Senn seems to have been printed labels, and undoubtedly the most convinced that Stainer . -

Die Sammlung Historischer Streichinstrumente Der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank

OESTERREICHISCHE NATIONALBANK EUROSYSTEM Die Sammlung historischer Streichinstrumente der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank The collection of Historical String Instruments of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank Inhaltsverzeichnis Contents Impressum Medieninhaberin: Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Otto-Wagner-Platz 3, 1090 Wien, T: (+43 1) 404 20-6605, F: (+43 1) 404 20-6697, www.oenb.at Redaktion: Mag. Brigitte Alizadeh-Gruber, Muna Kadum, Martina Leitner, Mag. Irene Mühldorf Grafik, Layout und Satz: Melanie Schuhmacher Fotos: © Graphisches Atelier Neumann, Wien Druck: Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Abteilung für Öffentlichkeitsarbeit und Publikationen, Gruppe Multimedia-, Internet- und Print-Service. © Oesterreichische Nationalbank, 2013. Streichinstrumente/ String Instruments 9 Amati Andrea 10 Violoncello, Cremona, spätes 16. Jh. 10 Bergonzi Carlo 12 Violine, Cremona 1723 12 Violine, Cremona nach 1724 14 Bergonzi Michelangelo 16 Violine, Cremona um 1740 16 Violine, „ex Hamma-Segelman“, Cremona um 1750 18 Camilli Camillus 20 Violine, Mantua 1736 20 Ceruti Giovanni Battista 22 Viola, Cremona um 1810 22 Gagliano Alessandro 24 Violoncello, Neapel ca. 1710 24 Grancino Giovanni 26 Violoncello, „ex Piatti“ – „ex Dunlop“, Mailand 1706 26 Guadagnini Giovanni Battista 28 Violoncello, „ex von Zweygberg“, Piacenza 174. 28 Violine, Mailand 1749 30 Violine, „ex Meinel“, Turin um 1770–1775 32 Violine, Turin 1772 34 Violine, „Mantegazza“, Turin 1774 36 Violine, Turin 177. 38 Viola, Turin 1784 40 Guarneri Andrea 42 Violine, Cremona, Mitte 17. Jh. 42 Guarneri del Gesù Giuseppe 44 Violine, „ex Sorkin“, Cremona 1731 44 Violine, „ex Guilet“, Cremona nach 1732 46 Violine, „ex Carrodus“, Cremona 1741 48 Lorenzini Gaspare 50 Violine, Piacenza um 1760 50 Maggini Giovanni Paolo 52 Viola, Brescia, frühes 17. Jh. 52 Montagnana Domenico 54 Violine, Venedig 1727 54 Seraphin Sanctus 56 Violine, Venedig 1733 56 Violine, „ex Hamma“, Venedig nach 1748 58 Silvestre Pierre 60 Violine, „ex Moser“, Lyon ca. -

Reconstructing Lost Instruments Praetorius’S Syntagma Musicum and the Violin Family C

Prejeto / received: 3. 5. 2019. Odobreno / accepted: 12. 9. 2019. doi: 10.3986/dmd15.1-2.07 RECONSTRUCTING LOST INSTRUMENTS Praetorius’S Syntagma musicum and the Violin Family C. 1619 Matthew Zeller Duke University Izvleček: Knjigi De organographia in Theatrum Abstract: Michael Praetorius’s De organographia instrumentorum Michaela Praetoriusa vsebujeta and Theatrum instrumentorum provide valuable dragocene namige, ki pomagajo pri poznavanju clues that contribute to a new understanding glasbil iz družine violin okoli leta 1619; številna of the violin family c. 1619, many surviving ex- preživela glasbila so manjša, kot so bili izvirniki amples of which are reduced in size from their v 16. in 17. stoletju. Podatki o preživelih glas- sixteenth- and seventeenth-century dimensions. bilih – predvsem izdelki družine Amati – skupaj The record of surviving instruments – especially z metrologijo, sekundarno dokumentacijo in those of the Amati family – alongside metrologic, ikonografskim gradivom kažejo na to, da je documentary and iconographic evidence shows Michael Praetorius opisal veliko glasbilo, po that Michael Praetorius describes a large in- velikosti izjemno podobno violončelu (basso strument conforming remarkably well to the da braccio),kar je odličen primer predstavitve original dimensions of the basso da braccio glasbila iz družine violin in točne uglasitve, kot (violoncello), as well as furnishing an excellent so jih poznali v času izida Praetoriusovega dela. scale representation of the violin family as it was at the time of these works’ -

A Prima Vista

A PRIMA VISTA a survey of reprints and of recent publications 2002/1 BROEKMANS & VAN POPPEL Van Baerlestraat 92-94 Postbus 75228 1070 AE AMSTERDAM sheet music: 020-6796575 CDs: 020-6751653/fax: 020-6646759 also on INTERNET: www.broekmans.com e-mail: [email protected] 2 CONTENTS A PRIMA VISTA 2002/1 PAGE HEADING 03 PIANO 2-HANDS 07 PIANO 4-HANDS, 2 AND MORE PIANOS, HARPSICHORD 08 ORGAN 09 KEYBOARD 1 STRING INSTRUMENT WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 10 VIOLIN SOLO, VIOLA SOLO 1 STRING INSTRUMENT WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, piano unless stated otherwise: 11 VIOLIN WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 12 VIOLIN PLAY-ALONG 13 VIOLA WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, CELLO WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 14 VIOLA DA GAMBA WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 14 2 AND MORE STRING INSTRUMENTS WITH AND WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 1 WIND INSTRUMENT WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 18 FLUTE SOLO, OBOE SOLO 19 CLARINET SOLO, SAXOPHONE SOLO, BASSOON SOLO, TRUMPET SOLO 20 HORN SOLO, TROMBONE SOLO, TUBA SOLO 1 WIND INSTRUMENT WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, piano unless stated otherwise: 20 PICCOLO WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, FLUTE WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 22 FLUTE PLAY-ALONG, ALTO FLUTE WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 23 OBOE WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, OBOE PLAY-ALONG, CLARINET WIT ACCOMPANIMENT 24 CLARINET PLAY-ALONG 25 BASSETHORN WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, SAXOPHONE WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 27 SAXOPHONE PLAY-ALONG 28 BASSOON WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, TRUMPET WIT ACCOMPANIMENT 29 TRUMPET PLAY-ALONG, HORN WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 30 TROMBONE WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, TROMBONE PLAY-ALONG 31 TUBA WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, EUPHONIUM PLAY-ALONG 2 AND MORE WIND INSTRUMENTS WITH AND WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 31 2 AND MORE WOODWIND -

The Strad Magazine

FRESH THINKING WOOD DENSITOMETRY MATERIAL Were the old Cremonese luthiers really using better woods than those available to other makers FACTS in Europe? TERRY BORMAN and BEREND STOEL present a study of density that seems to suggest otherwise Violins await testing on a CT scanner gantry S ALL LUTHIERS ARE WELL AWARE, of Stradivari. To test this conjecture, we set out to compare the business of making an instrument of the the wood employed by the classical Cremonese makers with violin family is fraught with pitfalls. There that used by other makers, during the same time period but are countless ways to ruin the sound of the from various regions across Europe. This would eliminate one fi nished product, starting with possibly the variable – the ageing of the wood – and allow the tracking of Amost fundamental decision of all: what wood to use. In the past geographical and topographical variation. In particular, we 35 years we have seen our knowledge of the available options wanted to investigate the densities of the woods involved, which expand greatly – and as we learn more about the different wood we felt could be the key to unlocking these secrets. choices, it is increasingly hard not to agonise over the decision. What are the characteristics we need as makers? Should we just WHY DENSITY? look for a specifi c grain line spacing, or a good split? Those were The three key properties of wood, from an instrument maker’s the characteristics that makers were once taught to watch out perspective, are density, stiffness (‘Young’s modulus’) and for, and yet results are diffi cult to repeat from instrument to damping (in its simplest terms, a measure of how long an object instrument when using the same pattern – suggesting these are will vibrate after being set in motion). -

A History of Mandolin Construction

1 - Mandolin History Chapter 1 - A History of Mandolin Construction here is a considerable amount written about the history of the mandolin, but littleT that looks at the way the instrument e marvellous has been built, rather than how it has been 16 string ullinger played, across the 300 years or so of its mandolin from 1925 existence. photo courtesy of ose interested in the classical mandolin ony ingham, ondon have tended to concentrate on the European bowlback mandolin with scant regard to the past century of American carved instruments. Similarly many American writers don’t pay great attention to anything that happened before Orville Gibson, so this introductory chapter is an attempt to give equal weight to developments on both sides of the Atlantic and to see the story of the mandolin as one of continuing evolution with the odd revolutionary change along the way. e history of the mandolin is not of a straightforward, lineal development, but one which intertwines with the stories of guitars, lutes and other stringed instruments over the past 1000 years. e formal, musicological definition of a (usually called the Neapolitan mandolin); mandolin is that of a chordophone of the instruments with a flat soundboard and short-necked lute family with four double back (sometimes known as a Portuguese courses of metal strings tuned g’-d’-a”-e”. style); and those with a carved soundboard ese are fixed to the end of the body using and back as developed by the Gibson a floating bridge and with a string length of company a century ago. -

A Brief History of the Violin

A Brief History of the Violin The violin is a descendant from the Viol family of instruments. This includes any stringed instrument that is fretted and/or bowed. It predecessors include the medieval fiddle, rebec, and lira da braccio. We can assume by paintings from that era, that the three string violin was in existence by at least 1520. By 1550, the top E string had been added and the Viola and Cello had emerged as part of the family of bowed string instruments still in use today. It is thought by many that the violin probably went through its greatest transformation in Italy from 1520 through 1650. Famous violin makers such as the Amati family were pivotal in establishing the basic proportions of the violin, viola, and cello. This family’s contributions to the art of violin making were evident not only in the improvement of the instrument itself, but also in the apprenticeships of subsequent gifted makers including Andrea Guarneri, Francesco Rugeri, and Antonio Stradivari. Stradivari, recognized as the greatest violin maker in history, went on to finalize and refine the violin’s form and symmetry. Makers including Stradivari, however, continued to experiment through the 19th century with archings, overall length, the angle of the neck, and bridge height. As violin repertoire became more demanding, the instrument evolved to meet the requirements of the soloist and larger concert hall. The changing styles in music played off of the advancement of the instrument and visa versa. In the 19th century, the modern violin became established. The modern bow had been invented by Francois Tourte (1747-1835). -

Open Model Specification Sheet As

Model name: A-48 Archive of guitar models Guitar type: 6-string Body shape: Auditorium Top: AAA Engleman spruce Back & Sides: Macassar ebony (Style 48) Neck: Cedro Soundhole rosette: Premium Design with two woods and abalone purfling Headstock: Slotted headstock Headstock veneer: Ebony Body bindings: Yew Headstock bindings: Yew Fingerboard bindings: Yew Body purfling: Abalone purfling on soundboard Fingerboard: Ebony Headstock inlays: White MOP Lakewood logo Fingerboard inlays: none Heel cap: Ebony Nut: Bone Neck width at nut: 46 mm (1.81 inch) Neck width at body-neck-joint: 57 mm (2.24 inch) Neck thickness: 21mm to 23mm (0.83 to 0.91 inch) Neck profile: C-shape Body-neck-joint: at 12th fret Scale length: 650 mm (25.6 inch) Frets: 19 frets Bridge: Ebony Bridge saddle: Bone String spacing at bridge: 57mm (2.24 inch) Bridge pins: Ebony with pearl dot Tuners: Schaller old style gold Tuner buttons: Gold Body finish: High-gloss finish Neck finish: Satin-gloss, filled grain End pin: Lakewood end pin (matching bridge pins) Strings: Elixir Nanoweb Phosphorbronze .012 - .053 (light) Case: Hiscox Lakewood hard case Recommended retail price: $ 0 incl. 0.0% VAT You've had a Lakewood guitar for a long time and now you cannot find it within our guitar range? Maybe you are luckier here. This is a list of older guitar models that have been taken out of the series program. Most of them are still available via our customshop. This Guitar was part of the Premium range from 2005 until 2006. Specification sheet A-48 - Copyright 2021 by Lakewood Guitars. -

Searching for Giuseppe Guarneri Del Gesù: a Paper-Chase and a Proposition

Searching for Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù: a paper-chase and a proposition Nicholas Sackman © 2021 During the past 200 years various investigators have laboured to unravel the strands of confusion which have surrounded the identity and life-story of the violin maker known as Bartolomeo Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù. Early-nineteenth-century commentators – Count Cozio di Salabue, for example – struggled to make sense of the situation through the physical evidence of the instruments they owned, the instruments’ internal labels, and the ‘understanding’ of contemporary restorers, dealers, and players; regrettably, misinformation was often passed from one writer to another, sometimes acquiring elaborations on the way. When research began into Cremonese archives the identity of individuals (together with their dates of birth and death) were sometimes announced as having been securely determined only for subsequent investigations to show that this certainty was illusory, the situation being further complicated by the Italian habit of christening a new- born son with multiple given names (frequently repeating those already given to close relatives) and then one or more of the given names apparently being unused during that new-born’s lifetime. During the early twentieth century misunderstandings were still frequent, and even today uncertainties still remain, with aspects of del Gesù’s chronology rendered opaque through contradictory or no documentation. The following account examines the documentary and physical evidence. ***** NB: During the first decades of the nineteenth century there existed violins with internal labels showing dates from the 1720s and the inscription Joseph Guarnerius Andrea Nepos. The Latin Dictionary compiled by Charlton T Lewis and Charles Short provides copious citations drawn from Classical Latin (as written and spoken during the period when the Roman Empire was at its peak, i.e.