Reconstructing Lost Instruments Praetorius’S Syntagma Musicum and the Violin Family C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

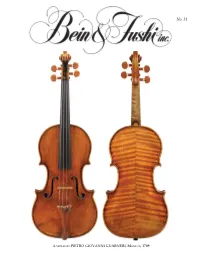

B&F Magazine Issue 31

No. 31 A VIOLIN BY PIETRO GIOVANNI GUARNERI, MANTUA, 1709 superb instruments loaned to them by the Arrisons, gave spectacular performances and received standing ovations. Our profound thanks go to Karen and Clement Arrison for their dedication to preserving our classical music traditions and helping rising stars launch their careers over many years. Our feature is on page 11. Violinist William Hagen Wins Third Prize at the Queen Elisabeth International Dear Friends, Competition With a very productive summer coming to a close, I am Bravo to Bein & Fushi customer delighted to be able to tell you about a few of our recent and dear friend William Hagen for notable sales. The exquisite “Posselt, Philipp” Giuseppe being awarded third prize at the Guarneri del Gesù of 1732 is one of very few instruments Queen Elisabeth Competition in named after women: American virtuoso Ruth Posselt (1911- Belgium. He is the highest ranking 2007) and amateur violinist Renee Philipp of Rotterdam, American winner since 1980. who acquired the violin in 1918. And exceptional violins by Hagen was the second prize winner Camillo Camilli and Santo Serafin along with a marvelous of the Fritz Kreisler International viola bow by Dominique Peccatte are now in the very gifted Music Competition in 2014. He has hands of discerning artists. I am so proud of our sales staff’s Photo: Richard Busath attended the Colburn School where amazing ability to help musicians find their ideal match in an he studied with Robert Lipsett and Juilliardilli d wherehh he was instrument or bow. a student of Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho. -

The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck

Performance Practice Review Volume 9 Article 7 Number 1 Spring The aB roque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Vanscheeuwijck, Marc (1996) "The aB roque Cello and Its Performance," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 9: No. 1, Article 7. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199609.01.07 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Baroque Instruments The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck The instrument we now call a cello (or violoncello) apparently deve- loped during the first decades of the 16th century from a combina- tion of various string instruments of popular European origin (espe- cially the rebecs) and the vielle. Although nothing precludes our hypothesizing that the bass of the violins appeared at the same time as the other members of that family, the earliest evidence of its existence is to be found in the treatises of Agricola,1 Gerle,2 Lanfranco,3 and Jambe de Fer.4 Also significant is a fresco (1540- 42) attributed to Giulio Cesare Luini in Varallo Sesia in northern Italy, in which an early cello is represented (see Fig. 1). 1 Martin Agricola, Musica instrumentalis deudsch (Wittenberg, 1529; enlarged 5th ed., 1545), f. XLVIr., f. XLVIIIr., and f. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

Early Fifteenth Century

CONTENTS CHAPTER I ORIENTAL AND GREEK MUSIC Section Item Number Page Number ORIENTAL MUSIC Ι-6 ... 3 Chinese; Japanese; Siamese; Hindu; Arabian; Jewish GREEK MUSIC 7-8 .... 9 Greek; Byzantine CHAPTER II EARLY MEDIEVAL MUSIC (400-1300) LITURGICAL MONOPHONY 9-16 .... 10 Ambrosian Hymns; Ambrosian Chant; Gregorian Chant; Sequences RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR MONOPHONY 17-24 .... 14 Latin Lyrics; Troubadours; Trouvères; Minnesingers; Laude; Can- tigas; English Songs; Mastersingers EARLY POLYPHONY 25-29 .... 21 Parallel Organum; Free Organum; Melismatic Organum; Benedica- mus Domino: Plainsong, Organa, Clausulae, Motets; Organum THIRTEENTH-CENTURY POLYPHONY . 30-39 .... 30 Clausulae; Organum; Motets; Petrus de Cruce; Adam de la Halle; Trope; Conductus THIRTEENTH-CENTURY DANCES 40-41 .... 42 CHAPTER III LATE MEDIEVAL MUSIC (1300-1400) ENGLISH 42 .... 44 Sumer Is Icumen In FRENCH 43-48,56 . 45,60 Roman de Fauvel; Guillaume de Machaut; Jacopin Selesses; Baude Cordier; Guillaume Legrant ITALIAN 49-55,59 · • · 52.63 Jacopo da Bologna; Giovanni da Florentia; Ghirardello da Firenze; Francesco Landini; Johannes Ciconia; Dances χ Section Item Number Page Number ENGLISH 57-58 .... 61 School o£ Worcester; Organ Estampie GERMAN 60 .... 64 Oswald von Wolkenstein CHAPTER IV EARLY FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH 61-64 .... 65 John Dunstable; Lionel Power; Damett FRENCH 65-72 .... 70 Guillaume Dufay; Gilles Binchois; Arnold de Lantins; Hugo de Lantins CHAPTER V LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY FLEMISH 73-78 .... 76 Johannes Ockeghem; Jacob Obrecht FRENCH 79 .... 83 Loyset Compère GERMAN 80-84 . ... 84 Heinrich Finck; Conrad Paumann; Glogauer Liederbuch; Adam Ile- borgh; Buxheim Organ Book; Leonhard Kleber; Hans Kotter ENGLISH 85-86 .... 89 Song; Robert Cornysh; Cooper CHAPTER VI EARLY SIXTEENTH CENTURY VOCAL COMPOSITIONS 87,89-98 ... -

The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I

The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I Edited by Theodore Hoelty-Nickel Valparaiso, Indiana The greatest contribution of the Lutheran Church to the culture of Western civilization lies in the field of music. Our Lutheran University is therefore particularly happy over the fact that, under the guidance of Professor Theodore Hoelty-Nickel, head of its Department of Music, it has been able to make a definite contribution to the advancement of musical taste in the Lutheran Church of America. The essays of this volume, originally presented at the Seminar in Church Music during the summer of 1944, are an encouraging evidence of the growing appreciation of our unique musical heritage. O. P. Kretzmann The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I Table of Contents Foreword Opening Address -Prof. Theo. Hoelty-Nickel, Valparaiso, Ind. Benefits Derived from a More Scholarly Approach to the Rich Musical and Liturgical Heritage of the Lutheran Church -Prof. Walter E. Buszin, Concordia College, Fort Wayne, Ind. The Chorale—Artistic Weapon of the Lutheran Church -Dr. Hans Rosenwald, Chicago, Ill. Problems Connected with Editing Lutheran Church Music -Prof. Walter E. Buszin The Radio and Our Musical Heritage -Mr. Gerhard Schroth, University of Chicago, Chicago, Ill. Is the Musical Training at Our Synodical Institutions Adequate for the Preserving of Our Musical Heritage? -Dr. Theo. G. Stelzer, Concordia Teachers College, Seward, Nebr. Problems of the Church Organist -Mr. Herbert D. Bruening, St. Luke’s Lutheran Church, Chicago, Ill. Members of the Seminar, 1944 From The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church, Volume I (Valparaiso, Ind.: Valparaiso University, 1945). -

The Form of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites Daniel E. Prindle University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Composition Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Prindle, Daniel E., "The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 636. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/636 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2011 Master of Music in Music Theory © Copyright by Daniel E. Prindle 2011 All Rights Reserved ii THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________ Gary Karpinski, Chair _____________________________________ Miriam Whaples, Member _____________________________________ Brent Auerbach, Member ___________________________________ Jeffrey Cox, Department Head Department of Music and Dance iii DEDICATION To Michelle and Rhys. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge the generous sacrifice made by my family. -

Michael Praetorius's Theology of Music in Syntagma Musicum I (1615): a Politically and Confessionally Motivated Defense of Instruments in the Lutheran Liturgy

MICHAEL PRAETORIUS'S THEOLOGY OF MUSIC IN SYNTAGMA MUSICUM I (1615): A POLITICALLY AND CONFESSIONALLY MOTIVATED DEFENSE OF INSTRUMENTS IN THE LUTHERAN LITURGY Zachary Alley A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2014 Committee: Arne Spohr, Advisor Mary Natvig ii ABSTRACT Arne Spohr, Advisor The use of instruments in the liturgy was a controversial issue in the early church and remained at the center of debate during the Reformation. Michael Praetorius (1571-1621), a Lutheran composer under the employment of Duke Heinrich Julius of Braunschweig-Lüneburg, made the most significant contribution to this perpetual debate in publishing Syntagma musicum I—more substantial than any Protestant theologian including Martin Luther. Praetorius's theological discussion is based on scripture, the discourse of early church fathers, and Lutheran theology in defending the liturgy, especially the use of instruments in Syntagma musicum I. In light of the political and religious instability throughout Europe it is clear that Syntagma musicum I was also a response—or even a potential solution—to political circumstances, both locally and in the Holy Roman Empire. In the context of the strengthening counter-reformed Catholic Church in the late sixteenth century, Lutheran territories sought support from Reformed church territories (i.e., Calvinists). This led some Lutheran princes to gradually grow more sympathetic to Calvinism or, in some cases, officially shift confessional systems. In Syntagma musicum I Praetorius called on Lutheran leaders—prince-bishops named in the dedication by territory— specifically several North German territories including Brandenburg and the home of his employer in Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel, to maintain Luther's reforms and defend the church they were entrusted to protect, reminding them that their salvation was at stake. -

Jan. 6, 1970 M

Jan. 6, 1970 M. TANSKY 3,487,740 VIOLIN WITH TIMBRE BASS BAR Filed May 9, 1968 c?????? NivENTOR NA CA E TANSKY’ AORNEYS 3,487,740 United States Patent Office Patented Jan. 6, 1. 970 2 Still further objects and advantages of the present in 3,487,740 VIOLIN WITH TEMBRE BASSBAR Vention will readily become apparent to those skilled in the Michael Tansky, 541 Olive Ave., art to which the invention pertains on reference to the Long Beach, Calif. 90812 following detailed description. Filed May 9, 1968, Ser. No. 727,774 5 Description of the drawing ? . , Int. CI. G10d 1/02 0 The description refers to the accompanying drawing in U.S. C. 84-276 6 Claims which like reference characters refer to like parts through out the several views in which: FIGURE 1 is a longitudinal sectional view of the sound ABSTRACT OF THE DISCLOSURE O box of a violin showing the bass bar embodying my in A violin having an elongated, internally mounted bass vention; , ; bar with a continuous series of conical cavities extending FIGURE 2 is a view of the preferred bass bar, sepa along its inner longitudinal edge and facing the back of rated from the instrument as along one of its longitudinal the instrument. The bass bar results in the violin pro edges; w ` ? - . ducing pure, limpid tones while the cavities reduce the FIGURE3 is a view of the opposite longitudinal edge weight of the bass bar. Y. of the preferred bass bar; and : ... TSSSLSLSSSSLLLLL SLLS0L0LSLSTM SM FIGURE 4 is a fragmentary perspective view of the Background of the invention mid-section of the preferred bass bar. -

21St Century Consort Composer Performance List

21st Century Consort Composer List 1975 - 2016 Archive of performance recordings Hans Abrahamsen Winternacht (1976-78) 1986-12-06 (15:27) flute, clarinet, trumpet, French horn, piano, violin, cello, conductor John Adams Road Movies 2012-05-05 (15:59) violin, piano Hallelujah Junction 2016-02-06 (17:25) piano, piano Shaker Loops (1978) 2000-04-15 (26:34) violin, violin, violin, viola, cello, cello, contrabass, conductor Bruce Adolphe Machaut is My Beginning (1989) 1996-03-16 (5:01) violin, cello, flute, clarinet, piano Miguel Del Agui Clocks 2011-11-05 (20:46) violin, piano, viola, violin, cello Stephen Albert To Wake the Dead (1978) 1993-02-13 (27:24) soprano, violin, conductor Tribute (1988) 1995-04-08 (10:27) violin, piano Treestone (1984) 1991-11-02 (38:15) soprano, tenor, violin, violin, viola, cello, bass, trumpet, clarinet, French horn, flute, percussion, piano, conductor Songs from the Stone Harp (1988) 1989-03-18 (11:56) tenor, harp, cello, percussion Treestone (1978) 1984-03-17 (30:22) soprano, tenor, flute, clarinet, trumpet, horn, harp, violin, violin, viola, cello, bass, piano, percussion, conductor Into Eclipse (1981) 1985-11-02 (31:46) tenor, violin, violin, viola, cello, contrabass, flute, clarinet, piano, percussion, trumpet, horn, conductor Distant Hills Coming Nigh: "Flower of the Mountain" 2016-04-30 (16:44) double bass, clarinet, piano, viola, conductor, French horn, violin, soprano, flute, violin, oboe, bassoon, cello Tribute (1988) 2002-01-26 (9:55) violin, piano Into Eclipse [New Version for Cello Solo Prepared -

Die Sammlung Historischer Streichinstrumente Der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank

OESTERREICHISCHE NATIONALBANK EUROSYSTEM Die Sammlung historischer Streichinstrumente der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank The collection of Historical String Instruments of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank Inhaltsverzeichnis Contents Impressum Medieninhaberin: Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Otto-Wagner-Platz 3, 1090 Wien, T: (+43 1) 404 20-6605, F: (+43 1) 404 20-6697, www.oenb.at Redaktion: Mag. Brigitte Alizadeh-Gruber, Muna Kadum, Martina Leitner, Mag. Irene Mühldorf Grafik, Layout und Satz: Melanie Schuhmacher Fotos: © Graphisches Atelier Neumann, Wien Druck: Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Abteilung für Öffentlichkeitsarbeit und Publikationen, Gruppe Multimedia-, Internet- und Print-Service. © Oesterreichische Nationalbank, 2013. Streichinstrumente/ String Instruments 9 Amati Andrea 10 Violoncello, Cremona, spätes 16. Jh. 10 Bergonzi Carlo 12 Violine, Cremona 1723 12 Violine, Cremona nach 1724 14 Bergonzi Michelangelo 16 Violine, Cremona um 1740 16 Violine, „ex Hamma-Segelman“, Cremona um 1750 18 Camilli Camillus 20 Violine, Mantua 1736 20 Ceruti Giovanni Battista 22 Viola, Cremona um 1810 22 Gagliano Alessandro 24 Violoncello, Neapel ca. 1710 24 Grancino Giovanni 26 Violoncello, „ex Piatti“ – „ex Dunlop“, Mailand 1706 26 Guadagnini Giovanni Battista 28 Violoncello, „ex von Zweygberg“, Piacenza 174. 28 Violine, Mailand 1749 30 Violine, „ex Meinel“, Turin um 1770–1775 32 Violine, Turin 1772 34 Violine, „Mantegazza“, Turin 1774 36 Violine, Turin 177. 38 Viola, Turin 1784 40 Guarneri Andrea 42 Violine, Cremona, Mitte 17. Jh. 42 Guarneri del Gesù Giuseppe 44 Violine, „ex Sorkin“, Cremona 1731 44 Violine, „ex Guilet“, Cremona nach 1732 46 Violine, „ex Carrodus“, Cremona 1741 48 Lorenzini Gaspare 50 Violine, Piacenza um 1760 50 Maggini Giovanni Paolo 52 Viola, Brescia, frühes 17. Jh. 52 Montagnana Domenico 54 Violine, Venedig 1727 54 Seraphin Sanctus 56 Violine, Venedig 1733 56 Violine, „ex Hamma“, Venedig nach 1748 58 Silvestre Pierre 60 Violine, „ex Moser“, Lyon ca. -

Violin Detective

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS instruments have gone up in value after I found that their soundboards matched trees known to have been used by Stradivari; one subsequently sold at auction for more than four times its estimate. Many convincing for- KAMILA RATCLIFF geries were made in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but the science did not exist then. Forgers now are aware of dendro- chronology, and it could be a problem if they use wood from old chalets to build sophisti- cated copies of historical instruments. How about unintentional deceit? I never like to ‘kill’ a violin — reveal it as not what it seems. But if the wood does not match the claims, I investigate. I was recently sent photos of a violin supposedly made by an Italian craftsman who died in 1735. The wood dated to the 1760s, so I knew he could not have made it. But I did see strong cor- relations to instruments made by his sons and nephews who worked in the 1770s. So Peter Ratcliff restores and investigates violins from his workshop in Hove, UK. I deduced that the violin might have been damaged and an entirely new soundboard made after the craftsman’s death. The violin Q&A Peter Ratcliff was pulled from auction, but not before it had received bids of more than US$100,000. Will dendrochronology change the market? Violin detective I think it already has, and has called into Peter Ratcliff uses dendrochronology — tree-ring dating — to pin down the age and suggest the question some incorrect historical assump- provenance of stringed instruments. -

Improvisation in Vocal Contrapuntal Pedagogy

Performance Practice Review Volume 18 | Number 1 Article 3 Improvisation in Vocal Contrapuntal Pedagogy: An Appraisal of Italian Theoretical Treatises of the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries Valerio Morucci California State University, Sacramento Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Morucci, Valerio (2013) "Improvisation in Vocal Contrapuntal Pedagogy: An Appraisal of Italian Theoretical Treatises of the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 18: No. 1, Article 3. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.201318.01.03 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol18/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Improvisation in Vocal Contrapuntal Pedagogy: An Appraisal of Italian Theoretical Treatises of the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries Valerio Morucci The extemporaneous application of pre-assimilated compositional paradigms into musical performance retained a central position in the training of Medieval and Renais- sance musicians, specifically within the context of Western polyphonic practice.1 Recent scholarship has shown the significance of memorization in the oral transmission of plainchant and early polyphony.2 Attention has been particularly directed to aspects of orality and literacy in relation to “composition” (the term here applies to both written and oral), and, at the same time, studies correlated to fifteenth- and sixteenth-century contra- puntal theory, have mainly focused on the works of single theorists.3 The information we 1.