Searching for Giuseppe Guarneri Del Gesù: a Paper-Chase and a Proposition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stowell Make-Up

The Cambridge Companion to the CELLO Robin Stowell Professor of Music, Cardiff University The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 1RP,United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia © Cambridge University Press 1999 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1999 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Adobe Minion 10.75/14 pt, in QuarkXpress™ [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data ISBN 0 521 621011 hardback ISBN 0 521 629284 paperback Contents List of illustrations [page viii] Notes on the contributors [x] Preface [xiii] Acknowledgements [xv] List of abbreviations, fingering and notation [xvi] 21 The cello: origins and evolution John Dilworth [1] 22 The bow: its history and development John Dilworth [28] 23 Cello acoustics Bernard Richardson [37] 24 Masters of the Baroque and Classical eras Margaret Campbell [52] 25 Nineteenth-century virtuosi Margaret Campbell [61] 26 Masters of the twentieth century Margaret Campbell [73] 27 The concerto Robin Stowell and David Wyn Jones [92] 28 The sonata Robin Stowell [116] 29 Other solo repertory Robin Stowell [137] 10 Ensemble music: in the chamber and the orchestra Peter Allsop [160] 11 Technique, style and performing practice to c. -

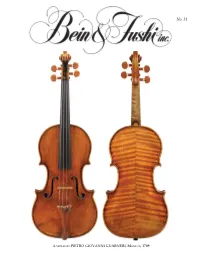

B&F Magazine Issue 31

No. 31 A VIOLIN BY PIETRO GIOVANNI GUARNERI, MANTUA, 1709 superb instruments loaned to them by the Arrisons, gave spectacular performances and received standing ovations. Our profound thanks go to Karen and Clement Arrison for their dedication to preserving our classical music traditions and helping rising stars launch their careers over many years. Our feature is on page 11. Violinist William Hagen Wins Third Prize at the Queen Elisabeth International Dear Friends, Competition With a very productive summer coming to a close, I am Bravo to Bein & Fushi customer delighted to be able to tell you about a few of our recent and dear friend William Hagen for notable sales. The exquisite “Posselt, Philipp” Giuseppe being awarded third prize at the Guarneri del Gesù of 1732 is one of very few instruments Queen Elisabeth Competition in named after women: American virtuoso Ruth Posselt (1911- Belgium. He is the highest ranking 2007) and amateur violinist Renee Philipp of Rotterdam, American winner since 1980. who acquired the violin in 1918. And exceptional violins by Hagen was the second prize winner Camillo Camilli and Santo Serafin along with a marvelous of the Fritz Kreisler International viola bow by Dominique Peccatte are now in the very gifted Music Competition in 2014. He has hands of discerning artists. I am so proud of our sales staff’s Photo: Richard Busath attended the Colburn School where amazing ability to help musicians find their ideal match in an he studied with Robert Lipsett and Juilliardilli d wherehh he was instrument or bow. a student of Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho. -

A Violin by Giuseppe Giovanni Battista Guarneri

141 A VIOLIN BY GIUSEPPE GIOVANNI BATTISTA GUARNERI Roger Hargrave, who has also researched and drawn the enclosed poster, discusses an outstanding example of the work of a member of the Guarneri family known as `Joseph Guarneri filius Andrea'. Andrea Guarneri was the first He may never have many details of instruments by of the Guarneri family of violin reached the heights of his Joseph filius at this period recall makers and an apprentice of contemporary, the Amati school, this type of Nicola Amati (he was actually varnish, in combination with registered as living in the house Antonio Stradivarius, but he the freer hand of Joseph, gives of Nicola Amati in 1641). Andrea's does rank as one of the the instruments a visual impact youngest son, whose work is il - greatest makers of all time. never achieved by an Amati or , lustrated here, was called. We should not forget he with the exception of Stradi - Giuseppe. Because several of the sired and trained the great vari, by any other classical Guarneri family bear the same del Gesu' maker before this time. christian names, individuals have traditionally been identified by a It should be said, however, suffix attached to their names. that the varnish of Joseph filius Thus, Giuseppe's brother is known as `Peter Guarneri varies considerably. It is not always of such out - of Mantua' to distinguish him from Giuseppe's son, standing quality the same can be said of Joseph's pro - who is known as `Peter Guarneri of Venice'. duction in general. If I were asked to describe the instruments of a few of the great Cremonese makers Giuseppe himself is called 'Giuseppe Guarneri filius in a single word, I would say that Amatis (all of them) Andrea' or, more simply, `Joseph filius' to distinguish are `refined', Stradivaris are `stately', del Gesus are him from his other son, the illustrious 'Giuseppe `rebellious' and the instruments of Joseph filius An - Guarneri del Gesu'. -

Antonio Stradivari "Servais" 1701

32 ANTONIO STRADIVARI "SERVAIS" 1701 The renowned "Servais" cello by Stradivari is examined by Roger Hargrave Photographs: Stewart Pollens Research Assistance: Julie Reed Technical Assistance: Gary Sturm (Smithsonian Institute) In 184.6 an Englishman, James Smithson, gave the bines the grandeur of the pre‑1700 instrument with US Government $500,000 to be used `for the increase the more masculine build which we could wish to and diffusion of knowledge among men.' This was the have met with in the work of the master's earlier beginning of the vast institution which now domi - years. nates the down‑town Washington skyline. It includes the J.F. Kennedy Centre for Performing Arts and the Something of the cello's history is certainly worth National Zoo, as well as many specialist museums, de - repeating here, since, as is often the case, much of picting the achievements of men in every conceiv - this is only to be found in rare or expensive publica - able field. From the Pony Express to the Skylab tions. The following are extracts from the Reminis - orbital space station, from Sandro Botticelli to Jack - cences of a Fiddle Dealer by David Laurie, a Scottish son Pollock this must surely be the largest museum violin dealer, who was a contemporary of J.B. Vuil - and arts complex anywhere in the world. Looking laume: around, one cannot help feeling that this is the sort While attending one of M. Jansen's private con - of place where somebody might be disappointed not certs, I had the pleasure of meeting M. Servais of Hal, to find the odd Strad! And indeed, if you can manage one of the most renowned violoncellists of the day . -

Violin Detective

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS instruments have gone up in value after I found that their soundboards matched trees known to have been used by Stradivari; one subsequently sold at auction for more than four times its estimate. Many convincing for- KAMILA RATCLIFF geries were made in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but the science did not exist then. Forgers now are aware of dendro- chronology, and it could be a problem if they use wood from old chalets to build sophisti- cated copies of historical instruments. How about unintentional deceit? I never like to ‘kill’ a violin — reveal it as not what it seems. But if the wood does not match the claims, I investigate. I was recently sent photos of a violin supposedly made by an Italian craftsman who died in 1735. The wood dated to the 1760s, so I knew he could not have made it. But I did see strong cor- relations to instruments made by his sons and nephews who worked in the 1770s. So Peter Ratcliff restores and investigates violins from his workshop in Hove, UK. I deduced that the violin might have been damaged and an entirely new soundboard made after the craftsman’s death. The violin Q&A Peter Ratcliff was pulled from auction, but not before it had received bids of more than US$100,000. Will dendrochronology change the market? Violin detective I think it already has, and has called into Peter Ratcliff uses dendrochronology — tree-ring dating — to pin down the age and suggest the question some incorrect historical assump- provenance of stringed instruments. -

The Working Methods of Guarneri Del Gesů and Their Influence Upon His

45 The Working Methods of Guarneri del Gesù and their Influence upon his Stylistic Development Text and Illustrations by Roger Graham Hargrave Please take time to read this warning! Although the greatest care has been taken while compiling this site it almost certainly contains many mistakes. As such its contents should be treated with extreme caution. Neither I nor my fellow contributors can accept responsibility for any losses resulting from information or opin - ions, new or old, which are reproduced here. Some of the ideas and information have already been superseded by subsequent research and de - velopment. (I have attempted to included a bibliography for further information on such pieces) In spite of this I believe that these articles are still of considerable use. For copyright or other practical reasons it has not been possible to reproduce all the illustrations. I have included the text for the series of posters that I created for the Strad magazine. While these posters are all still available, with one exception, they have been reproduced without the original accompanying text. The Labels mentions an early form of Del Gesù label, 98 later re - jected by the Hills as spurious. 99 The strongest evi - Before closing the body of the instrument, Del dence for its existence is found in the earlier Gesù fixed his label on the inside of the back, beneath notebooks of Count Cozio Di Salabue, who mentions the bass soundhole and roughly parallel to the centre four violins by the younger Giuseppe, all labelled and line. The labels which remain in their original posi - dated, from the period 1727 to 1730. -

Stradivari Violin Manual

Table of Contents 1. Disclaimer .................................................................................................................. 1 2. Welcome .................................................................................................................... 2 3. Document Conventions ............................................................................................... 3 4. Installation and Setup ................................................................................................. 4 5. About STRADIVARI VIOLIN ........................................................................................ 6 5.1. Key Features .................................................................................................... 6 6. Main Page .................................................................................................................. 8 7. Snapshots ................................................................................................................ 10 7.1. Overview of Snapshots ................................................................................... 10 7.2. Saving a User Snapshot ................................................................................. 10 7.3. Loading a Snapshot ......................................................................................... 11 7.4. Deleting a User Snapshot ............................................................................... 12 8. Articulation .............................................................................................................. -

Reunion in Cremona

Reunion in Cremona Reunion in Cremona is the name of the exhibition that is taking place at the Museo del Violino from September 21 2019 and October 18 2020. It is a “reunion” indeed between historical instruments made by the great violinmakers of the past and their birthplace. Within important exhibition are displayed 8 masterpieces of cremonese classical violinmaking tradition and a bow attributed to the workshop of the famous Antonio Stradivari that the National Music Museum of Vermillion, South Dakota decided to house to the Museo del Violino during the renovation of its building and the expansion of the exhibiting areas. The NMM is one of the most important musical instruments museums in the world, with more than 15000 pieces divided into different collections. The “Witten- Rawlins Collection” is of particular interest for Cremona. The instruments will be not only on display in the Museo del Violino, but also will undergo a complete non-invasive sientific examination in the Arvedi Labsof the University of Pavia within the Museo del Violino. Antonio e Girolamo Amati- violino “The King Henry IV”, 1595 ca. (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Girolamo Amati- violino, 1609 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Girolamo Amati- violino piccolo, 1613 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Nicolò Amati- violino, 1628 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Antonio Stradivari- mandolino coristo “The Cutler- Channel”, 1680 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Antonio Stradivari- chitarra “The Rawlins”, 1700 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) attribuito alla bottega di Antonio Stradivari- archetto da violino, 1700 ca. (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Nicola Bergonzi- viola 1781 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Lorenzo Storioni- violino 1/2, 1793 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) . -

PART I Dramatis Personae

PART I Chapter 1 Dramatis Personae Antonio Stradivari (c16491-18th December 1737) Antonio Stradivari lived and worked in the Italian town of Cremona, south-east of Milan. His earliest violins date from the mid-1660s and follow the example of his Cremonese predecessor Nicolò Amati (1596-1684) in terms of size, proportion, and style.2 Between 1690 and 1700 Stradivari produced violins with sound-boxes which were slightly longer than the norm of 355mm, but this ‘Long Pattern’ style was apparently abandoned at the start of his ‘Golden Period’ – approximately 1700. During the subsequent two decades he produced well-proportioned instruments with gentle and low arching across the front and back plates, the scrolls being outlined with black pigment to emphasise the edges of the spirals, and the instruments varnished with what some have claimed to have been a unique mixture of ingredients.3 By this time Antonio was certainly being helped in his workshop by two of his sons, Francesco and Omobono, and Roger Hargrave has suggested that Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù also worked in the Stradivari workshop.4 Charles Beare has indicated that, after 1720, Carlo Bergonzi (1683-1747) also participated in making instruments under Stradivari’s direction;5 however, Tim Ingles has stated that ‘Bergonzi was probably working independently in the early 1720s’.6 After 1720 Antonio’s energy, manual dexterity, and eyesight diminished (by then he was approximately 70 years old) and instruments from his final years are less well finished, with a more pronounced arch across the body and a distinctively dark tone. Antonio apparently continued to work until his death in 1737. -

The Strad Magazine

FRESH THINKING WOOD DENSITOMETRY MATERIAL Were the old Cremonese luthiers really using better woods than those available to other makers FACTS in Europe? TERRY BORMAN and BEREND STOEL present a study of density that seems to suggest otherwise Violins await testing on a CT scanner gantry S ALL LUTHIERS ARE WELL AWARE, of Stradivari. To test this conjecture, we set out to compare the business of making an instrument of the the wood employed by the classical Cremonese makers with violin family is fraught with pitfalls. There that used by other makers, during the same time period but are countless ways to ruin the sound of the from various regions across Europe. This would eliminate one fi nished product, starting with possibly the variable – the ageing of the wood – and allow the tracking of Amost fundamental decision of all: what wood to use. In the past geographical and topographical variation. In particular, we 35 years we have seen our knowledge of the available options wanted to investigate the densities of the woods involved, which expand greatly – and as we learn more about the different wood we felt could be the key to unlocking these secrets. choices, it is increasingly hard not to agonise over the decision. What are the characteristics we need as makers? Should we just WHY DENSITY? look for a specifi c grain line spacing, or a good split? Those were The three key properties of wood, from an instrument maker’s the characteristics that makers were once taught to watch out perspective, are density, stiffness (‘Young’s modulus’) and for, and yet results are diffi cult to repeat from instrument to damping (in its simplest terms, a measure of how long an object instrument when using the same pattern – suggesting these are will vibrate after being set in motion). -

A Brief History of the Violin

A Brief History of the Violin The violin is a descendant from the Viol family of instruments. This includes any stringed instrument that is fretted and/or bowed. It predecessors include the medieval fiddle, rebec, and lira da braccio. We can assume by paintings from that era, that the three string violin was in existence by at least 1520. By 1550, the top E string had been added and the Viola and Cello had emerged as part of the family of bowed string instruments still in use today. It is thought by many that the violin probably went through its greatest transformation in Italy from 1520 through 1650. Famous violin makers such as the Amati family were pivotal in establishing the basic proportions of the violin, viola, and cello. This family’s contributions to the art of violin making were evident not only in the improvement of the instrument itself, but also in the apprenticeships of subsequent gifted makers including Andrea Guarneri, Francesco Rugeri, and Antonio Stradivari. Stradivari, recognized as the greatest violin maker in history, went on to finalize and refine the violin’s form and symmetry. Makers including Stradivari, however, continued to experiment through the 19th century with archings, overall length, the angle of the neck, and bridge height. As violin repertoire became more demanding, the instrument evolved to meet the requirements of the soloist and larger concert hall. The changing styles in music played off of the advancement of the instrument and visa versa. In the 19th century, the modern violin became established. The modern bow had been invented by Francois Tourte (1747-1835). -

The History of the King Violincello Created by Andrea Amati(1505-1577)

May 2011 Volume 3 Magazine for Strings The History of The King Violincello created by Andrea Amati(1505-1577) YoYo Ma: Forging a Career in Music The Art of the Luthier The Music of Mozart, Become Inspired! The History of The King Violincello 2-10 created by Andrea Amati (1505-1577) Peggy Connor Forging a Career in Music 11-30 Inspiring advice from Yo Yo Ma The Art of the Luthier 31-35 Features A delicate art Harold Golden The Music of Mozart 36-45 Be inspired! Thomas Smith The Newest Juilllard Prodigy 46-57 Meet an amazing violinist Peggy Connor Priceless Violins of Cremona, Italy 58-63 A tour of the Museum of Cremona John Davis Suzuki Students 64-72 Observe how they learn Harold Golden Chicago Symphony Cellists 73-84 The newest generation John Davis The Latest Trends in the Music 85-94 A discussion with contemporary composers Eliza Jones Identifying a Young Prodigy 95-101 What defines truly gifted? Thomas Smith Orchestral Performance Schedules 102-105 May-Sept. Employment Opportunities 106-110 May 2011 May 2011 1 The History of The King Violincello Giuseppe (del Gesu) (1698-1744), Antonio Stradivari (1644-1737) Created by Andrea Amati, 1505-1577, Cremona, Italy of Cremona- and two of his sons, By Peggy Connor Francesco Stradivari (1671-1743) Omobono Stradivari (1679-1742), Jacob Stainer(1617-1683) of Absom The violin emerged from northern Italy Amati instruments that have survived. in Tyrol in the early 16th century, preceeded and One of oldest “surviving” dated violin, is Documented resident apprentices of the evolving from three likely fretted and non the “Charles IX” by Andrea Amati, made in Nicolo Amati workshop: fretted, stringed instruments: the rebec, the Cremona in1560.