PART I Dramatis Personae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B&F Magazine Issue 31

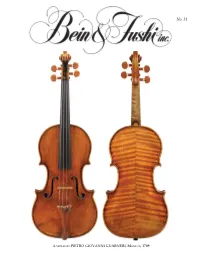

No. 31 A VIOLIN BY PIETRO GIOVANNI GUARNERI, MANTUA, 1709 superb instruments loaned to them by the Arrisons, gave spectacular performances and received standing ovations. Our profound thanks go to Karen and Clement Arrison for their dedication to preserving our classical music traditions and helping rising stars launch their careers over many years. Our feature is on page 11. Violinist William Hagen Wins Third Prize at the Queen Elisabeth International Dear Friends, Competition With a very productive summer coming to a close, I am Bravo to Bein & Fushi customer delighted to be able to tell you about a few of our recent and dear friend William Hagen for notable sales. The exquisite “Posselt, Philipp” Giuseppe being awarded third prize at the Guarneri del Gesù of 1732 is one of very few instruments Queen Elisabeth Competition in named after women: American virtuoso Ruth Posselt (1911- Belgium. He is the highest ranking 2007) and amateur violinist Renee Philipp of Rotterdam, American winner since 1980. who acquired the violin in 1918. And exceptional violins by Hagen was the second prize winner Camillo Camilli and Santo Serafin along with a marvelous of the Fritz Kreisler International viola bow by Dominique Peccatte are now in the very gifted Music Competition in 2014. He has hands of discerning artists. I am so proud of our sales staff’s Photo: Richard Busath attended the Colburn School where amazing ability to help musicians find their ideal match in an he studied with Robert Lipsett and Juilliardilli d wherehh he was instrument or bow. a student of Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho. -

Antonio Stradivari "Servais" 1701

32 ANTONIO STRADIVARI "SERVAIS" 1701 The renowned "Servais" cello by Stradivari is examined by Roger Hargrave Photographs: Stewart Pollens Research Assistance: Julie Reed Technical Assistance: Gary Sturm (Smithsonian Institute) In 184.6 an Englishman, James Smithson, gave the bines the grandeur of the pre‑1700 instrument with US Government $500,000 to be used `for the increase the more masculine build which we could wish to and diffusion of knowledge among men.' This was the have met with in the work of the master's earlier beginning of the vast institution which now domi - years. nates the down‑town Washington skyline. It includes the J.F. Kennedy Centre for Performing Arts and the Something of the cello's history is certainly worth National Zoo, as well as many specialist museums, de - repeating here, since, as is often the case, much of picting the achievements of men in every conceiv - this is only to be found in rare or expensive publica - able field. From the Pony Express to the Skylab tions. The following are extracts from the Reminis - orbital space station, from Sandro Botticelli to Jack - cences of a Fiddle Dealer by David Laurie, a Scottish son Pollock this must surely be the largest museum violin dealer, who was a contemporary of J.B. Vuil - and arts complex anywhere in the world. Looking laume: around, one cannot help feeling that this is the sort While attending one of M. Jansen's private con - of place where somebody might be disappointed not certs, I had the pleasure of meeting M. Servais of Hal, to find the odd Strad! And indeed, if you can manage one of the most renowned violoncellists of the day . -

Violin Detective

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS instruments have gone up in value after I found that their soundboards matched trees known to have been used by Stradivari; one subsequently sold at auction for more than four times its estimate. Many convincing for- KAMILA RATCLIFF geries were made in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but the science did not exist then. Forgers now are aware of dendro- chronology, and it could be a problem if they use wood from old chalets to build sophisti- cated copies of historical instruments. How about unintentional deceit? I never like to ‘kill’ a violin — reveal it as not what it seems. But if the wood does not match the claims, I investigate. I was recently sent photos of a violin supposedly made by an Italian craftsman who died in 1735. The wood dated to the 1760s, so I knew he could not have made it. But I did see strong cor- relations to instruments made by his sons and nephews who worked in the 1770s. So Peter Ratcliff restores and investigates violins from his workshop in Hove, UK. I deduced that the violin might have been damaged and an entirely new soundboard made after the craftsman’s death. The violin Q&A Peter Ratcliff was pulled from auction, but not before it had received bids of more than US$100,000. Will dendrochronology change the market? Violin detective I think it already has, and has called into Peter Ratcliff uses dendrochronology — tree-ring dating — to pin down the age and suggest the question some incorrect historical assump- provenance of stringed instruments. -

Stradivari Violin Manual

Table of Contents 1. Disclaimer .................................................................................................................. 1 2. Welcome .................................................................................................................... 2 3. Document Conventions ............................................................................................... 3 4. Installation and Setup ................................................................................................. 4 5. About STRADIVARI VIOLIN ........................................................................................ 6 5.1. Key Features .................................................................................................... 6 6. Main Page .................................................................................................................. 8 7. Snapshots ................................................................................................................ 10 7.1. Overview of Snapshots ................................................................................... 10 7.2. Saving a User Snapshot ................................................................................. 10 7.3. Loading a Snapshot ......................................................................................... 11 7.4. Deleting a User Snapshot ............................................................................... 12 8. Articulation .............................................................................................................. -

Reunion in Cremona

Reunion in Cremona Reunion in Cremona is the name of the exhibition that is taking place at the Museo del Violino from September 21 2019 and October 18 2020. It is a “reunion” indeed between historical instruments made by the great violinmakers of the past and their birthplace. Within important exhibition are displayed 8 masterpieces of cremonese classical violinmaking tradition and a bow attributed to the workshop of the famous Antonio Stradivari that the National Music Museum of Vermillion, South Dakota decided to house to the Museo del Violino during the renovation of its building and the expansion of the exhibiting areas. The NMM is one of the most important musical instruments museums in the world, with more than 15000 pieces divided into different collections. The “Witten- Rawlins Collection” is of particular interest for Cremona. The instruments will be not only on display in the Museo del Violino, but also will undergo a complete non-invasive sientific examination in the Arvedi Labsof the University of Pavia within the Museo del Violino. Antonio e Girolamo Amati- violino “The King Henry IV”, 1595 ca. (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Girolamo Amati- violino, 1609 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Girolamo Amati- violino piccolo, 1613 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Nicolò Amati- violino, 1628 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Antonio Stradivari- mandolino coristo “The Cutler- Channel”, 1680 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Antonio Stradivari- chitarra “The Rawlins”, 1700 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) attribuito alla bottega di Antonio Stradivari- archetto da violino, 1700 ca. (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Nicola Bergonzi- viola 1781 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Lorenzo Storioni- violino 1/2, 1793 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) . -

Searching for Giuseppe Guarneri Del Gesù: a Paper-Chase and a Proposition

Searching for Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù: a paper-chase and a proposition Nicholas Sackman © 2021 During the past 200 years various investigators have laboured to unravel the strands of confusion which have surrounded the identity and life-story of the violin maker known as Bartolomeo Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù. Early-nineteenth-century commentators – Count Cozio di Salabue, for example – struggled to make sense of the situation through the physical evidence of the instruments they owned, the instruments’ internal labels, and the ‘understanding’ of contemporary restorers, dealers, and players; regrettably, misinformation was often passed from one writer to another, sometimes acquiring elaborations on the way. When research began into Cremonese archives the identity of individuals (together with their dates of birth and death) were sometimes announced as having been securely determined only for subsequent investigations to show that this certainty was illusory, the situation being further complicated by the Italian habit of christening a new- born son with multiple given names (frequently repeating those already given to close relatives) and then one or more of the given names apparently being unused during that new-born’s lifetime. During the early twentieth century misunderstandings were still frequent, and even today uncertainties still remain, with aspects of del Gesù’s chronology rendered opaque through contradictory or no documentation. The following account examines the documentary and physical evidence. ***** NB: During the first decades of the nineteenth century there existed violins with internal labels showing dates from the 1720s and the inscription Joseph Guarnerius Andrea Nepos. The Latin Dictionary compiled by Charlton T Lewis and Charles Short provides copious citations drawn from Classical Latin (as written and spoken during the period when the Roman Empire was at its peak, i.e. -

1002775354-Alcorn.Pdf

3119 A STUDY OF STYLE AND INFLUENCE IN THE EARLY SCHOOLS OF VIOLIN MAKING CIRCA 1540 TO CIRCA 1800 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Allison A. Alcorn, B.Mus. Denton, Texas December, 1987 Alcorn, Allison A., A Study of Style and Influence in the Ear School of Violin Making circa 1540 to circa 1800. Master of Music (Musicology), December 1987, 172 pp., 2 tables, 31 figures, bibliography, 52 titles. Chapter I of this thesis details contemporary historical views on the origins of the violin and its terminology. Chapters II through VI study the methodologies of makers from Italy, the Germanic Countries, the Low Countries, France, and England, and highlights the aspects of these methodologies that show influence from one maker to another. Chapter VII deals with matters of imitation, copying, violin forgery and the differences between these categories. Chapter VIII presents a discussion of the manner in which various violin experts identify the maker of a violin. It briefly discusses a new movement that questions the current methods of authenti- cation, proposing that the dual role of "expert/dealer" does not lend itself to sufficient objectivity. The conclusion suggests that dealers, experts, curators, and musicologists alike must return to placing the first emphasis on the tra- dition of the craft rather than on the individual maker. o Copyright by Allison A. Alcorn TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES.... ............. ........viii LIST OF TABLES. ................ ... x Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . .............. *.. 1 Problems in Descriptive Terminology 3 The Origin of the Violin....... -

Stradivari's 'Tuscan' Viola

53 Stradivari’s 'Tuscan' viola ROGER HARGRAVE ON A RARE SURVIVING VIOLA FROM STRADIVARI'S MOST SKILLFUL PERIOD AS A CRAFTSMAN, MADE FOR PRINCE FERDINAND, SON OF THE GRAND DUKE OF TUSCANY. From documentary evidence we know that Stradi - illustrated here. Like the large tenor previously vari made more violas than those which have sur - mentioned, this viola, along with a violin and a cello, vived but we have no idea how many. Neither do we was delivered to Prince Ferdinand, son of the Grand seem to know how many still exist today. Duke of Tuscany, Cosimo III de Medici in Florence, in the autumn of 1690. All of these instruments are Estimates range from 10 to 18; you can take your known either as the `Tuscan' or the 'Medici' or some - pick. From the surviving relics of Stradivari's work - times even the `Tuscan Medici'. shop we can deduce that he made at least three types of viola form. The largest of these was the tenor form Stradivari's 1690s contralto viola mould was to do of which the good service He does not seem to have re designed the contralto after this date, and apparently even the most striking example is the viola housed in the last known Stradivari viola, the 'Gibson' 1734, was Instituto Cherubim in Florence (a notoriously diffi - constructed on this mould (see STRAD poster, Sep - cult museum to get into). The body length of this tember 1986). Any variations in the lengths and viola is 475mm or 18 3/4". (There must be a viola joke widths of the contraltos between 1690 and 1734 can there somewhere). -

Metropolitan Pavilion Proudly Presents Italian Masterpieces in New York

NEW YORK March 15-17, 2013 - Metropolitan Pavilion proudly presents Italian Masterpieces in New York The inspiration Historical musical instruments represent a very precious heritage. They continue to inspire contemporary violin makers, and they are able to communicate to the general public the values associated with art, culture and human endeavor. Mondomusica New York will bring to the U.S. some of the finest instruments ever made in violin-making history. They come from three of the most renowned collections in Italy, and some of them have never before been taken out of Italy. The instruments Cremona Municipal Collection The Municipal Building of Cremona houses one of the foremost strings collections in the world. These instruments characterize the history of the greatest violin-making dynasty ever known, originating in Cremona from the first half of the sixteenth century and developing until the first half of the eighteenth century. Mondomusica New York makes it possible to admire: Andrea Amati - Carlo IX, 1566 - violin In 1966, due to the efforts of Alfredo Puerari with the expert advice of Simone Fernando Sacconi, two masterpieces by great violin makers born in Cremona returned to the town: the Carlo IX di Francia, a violin constructed by Andrea Amati in 1566, and the Hammerle, made by Nicolò Amati in 1658. Both instruments, purchased by the Provincial Tourist Board in Cremona, came from the Rembert Wurlitzer Company in New York, which in turn had obtained them from the banker Henry Hottinger, a famous collector. Andrea Amati was able to determine the fundamental characteristics of the violin family of bowed stringed instruments, which with some small variations of proportion with regard to violas and violoncellos, are still in use today. -

National Music Museum to Allow Rare Stradivari Cello to Be Played at Historic Sioux City Symphony Event

12 Broadcaster Press October 6, 2015 www.broadcasteronline.com National Music Museum To Allow Rare Stradivari Cello To Be Played At Historic Sioux City Symphony Event Unique “Night At The tional Music Museum (NMM) ments.” At least two of Museum crown jewels — an ally different from the valved largest Javanese percussion will present “Night at the Mu- the instruments are being Antonio Stradivari violin, trumpet used by modern or- orchestra and consists of Museum” Concert seum.” This spectacular pro- incorporated into a public mandolin and guitar — in chestras, it is rarely heard in more than 50 instruments. Celebrates SCSO 100th duction will feature not only performance for the first the Museum’s renowned performance in part because The gamelan was acquired Anniversary the NMM’s Stradivari cello time in more than a century. Rawlins Gallery. so few pieces have been by the National Music Mu- Vermillion, SD/Sioux City, (played by Kenneth Olsen, The harpsichord has never “Some of the most com- written for it. “The keyed seum in 1999 as the result IA – For understandable of the Chicago Symphony previously been played with mon questions we get at the trumpet also requires an ex- of a generous gift from the reasons, the National Music Orchestra), but a historic a modern symphony orches- museum are ‘What does a ceptional musician — a true late Margaret Ann Everist Museum (Vermillion, South 1780 Calisto harpsichord, an tra. “It will also be a historic Stradivari sound like? Or specialist,” says Haskins. of Sioux City. Minneapolis- Dakota) very rarely per- 18th-century keyed trumpet, night for the classical music ‘Do you ever let anyone play “Only a handful of musicians based professional group mits its priceless Stradivari a special 1937 Martin alto world as a whole,” says them?’ Here are some an- throughout the world can Sumunar (Joko Sutrisno, instruments to leave the saxophone, and a stunning Haskins. -

Stradivarius: Origins and Legacy of the Greatest Violin Maker” June 4 & 5

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Celebrate all things Italian during the final weekend of “Stradivarius: Origins and Legacy of the Greatest Violin Maker” June 4 & 5 PHOENIX (May 17, 2016)—The time has come for the Musical Instrument Museum’s (MIM) one-of-a- kind exhibition “Stradivarius: Origins and Legacy of the Greatest Violin Maker” to close and MIM is ending the exhibition with an exciting cadenza! On June 4 and 5, come to MIM and “Experience Italy” with music, culture, food and more. Delight in an Italian Clarinet Classics performance as well as a violin and fiddle show. Enjoy Italian string music, learn about Italian violins and hear the interplay of violin and guitar in a special musical presentation. Learn about the Italian city of Cremona and its long history of violin making from Virginia Villa, director general of the Museo del Violino, and Paolo Bodini, president of the Friends of Stradivari. Be hands-on with a toe-tap piano and try making an Italian accordion. Don’t miss the delicious Italian-inspired food items for sale at Café Allegro, including minestrone vegetable soup, saffron risotto with wild mushrooms and cannoli. On the evening of June 5, the closing night of the Stradivarius exhibition, guests will have the opportunity to hear the “Artôt-Alard” violin, created by Antonio Stradivari in 1728, played by Endre Balogh live in concert. Balogh, owner of the violin, has performed as a soloist with the Berlin Philharmonic, Rotterdam Philharmonic, and Basel Symphony. He will be accompanied by classical guitarist and composer Brian Head. June 4 and 5 is the last chance for guests to see the Stradivarius exhibition, displaying five historical instruments from the 16th to the early 19th century and five contemporary masterworks from Europe and America representing the ongoing legacy of the Cremonese violin-making method. -

Folinari’, the Violin Was Made in Cremona, Italy, in Around 1725, Making It One of the Earliest Surviving ‘Del Gesù’ Instruments

Contact Mio Kobayashi +44 (0)20 7354 5763 [email protected] TARISIO TO AUCTION EARLY GUARNERI ‘DEL GESU’ VIOLIN IN JUNE 2012 24 April 2012, London An important early violin by the celebrated Cremonese maker Giuseppe Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ will be sold at auction by Tarisio on 25 June. Among the most sought after instruments in the world, ‘del Gesù’ violins rarely appear at auction and this example is expected to fetch upwards of £1.5 million. Known as the ‘Folinari’, the violin was made in Cremona, Italy, in around 1725, making it one of the earliest surviving ‘del Gesù’ instruments. It was discovered in Italy in the 1990s, and little is known about its previous history, although the violin is understood to have been owned by the Folinari family of wine makers. The violin is a typical early example showing the maker’s developing independence from his father, with whom he trained. It is in very good condition and is sold with certificates of authenticity from the three top contemporary experts, J.&A. Beare, Peter Biddulph and Bein & Fushi. Although Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ (1698–1744) ranks alongside Antonio Stradivari as one of the two greatest violin makers of all time, his instruments are much more rare, and almost never sold publicly. ‘Del Gesù’ violins have long been prized by soloists for their dark, powerful tone. Jason Price, Director of Tarisio, says, “The ‘Folinari’ will only be the second ‘del Gesù’ to be sold at auction in the past 10 years. It is a significant event and an excellent instrument, appealing to both players and collectors.” The violin will be exhibited in London in June, with bidding held online at tarisio.com.