Antonio Stradivari, His Life and Work (1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B&F Magazine Issue 31

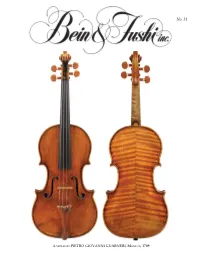

No. 31 A VIOLIN BY PIETRO GIOVANNI GUARNERI, MANTUA, 1709 superb instruments loaned to them by the Arrisons, gave spectacular performances and received standing ovations. Our profound thanks go to Karen and Clement Arrison for their dedication to preserving our classical music traditions and helping rising stars launch their careers over many years. Our feature is on page 11. Violinist William Hagen Wins Third Prize at the Queen Elisabeth International Dear Friends, Competition With a very productive summer coming to a close, I am Bravo to Bein & Fushi customer delighted to be able to tell you about a few of our recent and dear friend William Hagen for notable sales. The exquisite “Posselt, Philipp” Giuseppe being awarded third prize at the Guarneri del Gesù of 1732 is one of very few instruments Queen Elisabeth Competition in named after women: American virtuoso Ruth Posselt (1911- Belgium. He is the highest ranking 2007) and amateur violinist Renee Philipp of Rotterdam, American winner since 1980. who acquired the violin in 1918. And exceptional violins by Hagen was the second prize winner Camillo Camilli and Santo Serafin along with a marvelous of the Fritz Kreisler International viola bow by Dominique Peccatte are now in the very gifted Music Competition in 2014. He has hands of discerning artists. I am so proud of our sales staff’s Photo: Richard Busath attended the Colburn School where amazing ability to help musicians find their ideal match in an he studied with Robert Lipsett and Juilliardilli d wherehh he was instrument or bow. a student of Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho. -

A Violin by Jacobus Stainer 1679

146 A VIOLIN BY JACOBUS STAINER 1679 Roger Hargrave examines the construction and workmanship of this violin, which still retains its original undisturbed baroque neck. Roger Hargrave se penche sur la construction et la the necessary experience. facon d'un violon Jacobus Stainer, 1679, qui conserve Earlier Füssen in the Allgäu might have been a con - son manche baroque original encore intact. sideration, however, the ravages of the thirty years Roger Hargrave untersucht den Bau and die war had left Füssen bereft of skilled instrument mak - Machart einer Violine von Jacobus Stainer, 1679, ers, most of whom had found refuge in Italy and deren ursprünglicher barocker Hals unversehrt in particular in Venice, Rome and Padua. erhalten ist. Experts seem to agree that Stainer learned Jacobus Stainer is one of the very few non - his trade in Italy. And although this agree - Italian violin makers whose life and work have ment mostly rests on analogies of Stainer's been seriously researched. work, it is also known (from his writings) that he was familiar with the language. Furthermore, There have been a number of important publi - there are several oral traditions relating to an cations, most of which have drawn upon the Italian apprenticeship. As might be expected scholarly research work of the late Professor however these oral traditions are contra - Dr. Walter Senn. However, in spite of dictory, on the one hand saying that Senn's magnificent efforts, several im - Stainer worked in Venice and on the portant questions remain unanswered, other that he worked in Cremona. the exact dates of Stainer's birth and death, whether he used both written and Although Senn seems to have been printed labels, and undoubtedly the most convinced that Stainer . -

Antonio Stradivari "Servais" 1701

32 ANTONIO STRADIVARI "SERVAIS" 1701 The renowned "Servais" cello by Stradivari is examined by Roger Hargrave Photographs: Stewart Pollens Research Assistance: Julie Reed Technical Assistance: Gary Sturm (Smithsonian Institute) In 184.6 an Englishman, James Smithson, gave the bines the grandeur of the pre‑1700 instrument with US Government $500,000 to be used `for the increase the more masculine build which we could wish to and diffusion of knowledge among men.' This was the have met with in the work of the master's earlier beginning of the vast institution which now domi - years. nates the down‑town Washington skyline. It includes the J.F. Kennedy Centre for Performing Arts and the Something of the cello's history is certainly worth National Zoo, as well as many specialist museums, de - repeating here, since, as is often the case, much of picting the achievements of men in every conceiv - this is only to be found in rare or expensive publica - able field. From the Pony Express to the Skylab tions. The following are extracts from the Reminis - orbital space station, from Sandro Botticelli to Jack - cences of a Fiddle Dealer by David Laurie, a Scottish son Pollock this must surely be the largest museum violin dealer, who was a contemporary of J.B. Vuil - and arts complex anywhere in the world. Looking laume: around, one cannot help feeling that this is the sort While attending one of M. Jansen's private con - of place where somebody might be disappointed not certs, I had the pleasure of meeting M. Servais of Hal, to find the odd Strad! And indeed, if you can manage one of the most renowned violoncellists of the day . -

Die Sammlung Historischer Streichinstrumente Der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank

OESTERREICHISCHE NATIONALBANK EUROSYSTEM Die Sammlung historischer Streichinstrumente der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank The collection of Historical String Instruments of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank Inhaltsverzeichnis Contents Impressum Medieninhaberin: Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Otto-Wagner-Platz 3, 1090 Wien, T: (+43 1) 404 20-6605, F: (+43 1) 404 20-6697, www.oenb.at Redaktion: Mag. Brigitte Alizadeh-Gruber, Muna Kadum, Martina Leitner, Mag. Irene Mühldorf Grafik, Layout und Satz: Melanie Schuhmacher Fotos: © Graphisches Atelier Neumann, Wien Druck: Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Abteilung für Öffentlichkeitsarbeit und Publikationen, Gruppe Multimedia-, Internet- und Print-Service. © Oesterreichische Nationalbank, 2013. Streichinstrumente/ String Instruments 9 Amati Andrea 10 Violoncello, Cremona, spätes 16. Jh. 10 Bergonzi Carlo 12 Violine, Cremona 1723 12 Violine, Cremona nach 1724 14 Bergonzi Michelangelo 16 Violine, Cremona um 1740 16 Violine, „ex Hamma-Segelman“, Cremona um 1750 18 Camilli Camillus 20 Violine, Mantua 1736 20 Ceruti Giovanni Battista 22 Viola, Cremona um 1810 22 Gagliano Alessandro 24 Violoncello, Neapel ca. 1710 24 Grancino Giovanni 26 Violoncello, „ex Piatti“ – „ex Dunlop“, Mailand 1706 26 Guadagnini Giovanni Battista 28 Violoncello, „ex von Zweygberg“, Piacenza 174. 28 Violine, Mailand 1749 30 Violine, „ex Meinel“, Turin um 1770–1775 32 Violine, Turin 1772 34 Violine, „Mantegazza“, Turin 1774 36 Violine, Turin 177. 38 Viola, Turin 1784 40 Guarneri Andrea 42 Violine, Cremona, Mitte 17. Jh. 42 Guarneri del Gesù Giuseppe 44 Violine, „ex Sorkin“, Cremona 1731 44 Violine, „ex Guilet“, Cremona nach 1732 46 Violine, „ex Carrodus“, Cremona 1741 48 Lorenzini Gaspare 50 Violine, Piacenza um 1760 50 Maggini Giovanni Paolo 52 Viola, Brescia, frühes 17. Jh. 52 Montagnana Domenico 54 Violine, Venedig 1727 54 Seraphin Sanctus 56 Violine, Venedig 1733 56 Violine, „ex Hamma“, Venedig nach 1748 58 Silvestre Pierre 60 Violine, „ex Moser“, Lyon ca. -

Reconstructing Lost Instruments Praetorius’S Syntagma Musicum and the Violin Family C

Prejeto / received: 3. 5. 2019. Odobreno / accepted: 12. 9. 2019. doi: 10.3986/dmd15.1-2.07 RECONSTRUCTING LOST INSTRUMENTS Praetorius’S Syntagma musicum and the Violin Family C. 1619 Matthew Zeller Duke University Izvleček: Knjigi De organographia in Theatrum Abstract: Michael Praetorius’s De organographia instrumentorum Michaela Praetoriusa vsebujeta and Theatrum instrumentorum provide valuable dragocene namige, ki pomagajo pri poznavanju clues that contribute to a new understanding glasbil iz družine violin okoli leta 1619; številna of the violin family c. 1619, many surviving ex- preživela glasbila so manjša, kot so bili izvirniki amples of which are reduced in size from their v 16. in 17. stoletju. Podatki o preživelih glas- sixteenth- and seventeenth-century dimensions. bilih – predvsem izdelki družine Amati – skupaj The record of surviving instruments – especially z metrologijo, sekundarno dokumentacijo in those of the Amati family – alongside metrologic, ikonografskim gradivom kažejo na to, da je documentary and iconographic evidence shows Michael Praetorius opisal veliko glasbilo, po that Michael Praetorius describes a large in- velikosti izjemno podobno violončelu (basso strument conforming remarkably well to the da braccio),kar je odličen primer predstavitve original dimensions of the basso da braccio glasbila iz družine violin in točne uglasitve, kot (violoncello), as well as furnishing an excellent so jih poznali v času izida Praetoriusovega dela. scale representation of the violin family as it was at the time of these works’ -

Violin Detective

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS instruments have gone up in value after I found that their soundboards matched trees known to have been used by Stradivari; one subsequently sold at auction for more than four times its estimate. Many convincing for- KAMILA RATCLIFF geries were made in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but the science did not exist then. Forgers now are aware of dendro- chronology, and it could be a problem if they use wood from old chalets to build sophisti- cated copies of historical instruments. How about unintentional deceit? I never like to ‘kill’ a violin — reveal it as not what it seems. But if the wood does not match the claims, I investigate. I was recently sent photos of a violin supposedly made by an Italian craftsman who died in 1735. The wood dated to the 1760s, so I knew he could not have made it. But I did see strong cor- relations to instruments made by his sons and nephews who worked in the 1770s. So Peter Ratcliff restores and investigates violins from his workshop in Hove, UK. I deduced that the violin might have been damaged and an entirely new soundboard made after the craftsman’s death. The violin Q&A Peter Ratcliff was pulled from auction, but not before it had received bids of more than US$100,000. Will dendrochronology change the market? Violin detective I think it already has, and has called into Peter Ratcliff uses dendrochronology — tree-ring dating — to pin down the age and suggest the question some incorrect historical assump- provenance of stringed instruments. -

Five Late Baroque Works for String Instruments Transcribed for Clarinet and Piano

Five Late Baroque Works for String Instruments Transcribed for Clarinet and Piano A Performance Edition with Commentary D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of the The Ohio State University By Antoine Terrell Clark, M. M. Music Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2009 Document Committee: Approved By James Pyne, Co-Advisor ______________________ Co-Advisor Lois Rosow, Co-Advisor ______________________ Paul Robinson Co-Advisor Copyright by Antoine Terrell Clark 2009 Abstract Late Baroque works for string instruments are presented in performing editions for clarinet and piano: Giuseppe Tartini, Sonata in G Minor for Violin, and Violoncello or Harpsichord, op.1, no. 10, “Didone abbandonata”; Georg Philipp Telemann, Sonata in G Minor for Violin and Harpsichord, Twv 41:g1, and Sonata in D Major for Solo Viola da Gamba, Twv 40:1; Marin Marais, Les Folies d’ Espagne from Pièces de viole , Book 2; and Johann Sebastian Bach, Violoncello Suite No.1, BWV 1007. Understanding the capabilities of the string instruments is essential for sensitively translating the music to a clarinet idiom. Transcription issues confronted in creating this edition include matters of performance practice, range, notational inconsistencies in the sources, and instrumental idiom. ii Acknowledgements Special thanks is given to the following people for their assistance with my document: my doctoral committee members, Professors James Pyne, whose excellent clarinet instruction and knowledge enhanced my performance and interpretation of these works; Lois Rosow, whose patience, knowledge, and editorial wonders guided me in the creation of this document; and Paul Robinson and Robert Sorton, for helpful conversations about baroque music; Professor Kia-Hui Tan, for providing insight into baroque violin performance practice; David F. -

Stradivari Violin Manual

Table of Contents 1. Disclaimer .................................................................................................................. 1 2. Welcome .................................................................................................................... 2 3. Document Conventions ............................................................................................... 3 4. Installation and Setup ................................................................................................. 4 5. About STRADIVARI VIOLIN ........................................................................................ 6 5.1. Key Features .................................................................................................... 6 6. Main Page .................................................................................................................. 8 7. Snapshots ................................................................................................................ 10 7.1. Overview of Snapshots ................................................................................... 10 7.2. Saving a User Snapshot ................................................................................. 10 7.3. Loading a Snapshot ......................................................................................... 11 7.4. Deleting a User Snapshot ............................................................................... 12 8. Articulation .............................................................................................................. -

Reunion in Cremona

Reunion in Cremona Reunion in Cremona is the name of the exhibition that is taking place at the Museo del Violino from September 21 2019 and October 18 2020. It is a “reunion” indeed between historical instruments made by the great violinmakers of the past and their birthplace. Within important exhibition are displayed 8 masterpieces of cremonese classical violinmaking tradition and a bow attributed to the workshop of the famous Antonio Stradivari that the National Music Museum of Vermillion, South Dakota decided to house to the Museo del Violino during the renovation of its building and the expansion of the exhibiting areas. The NMM is one of the most important musical instruments museums in the world, with more than 15000 pieces divided into different collections. The “Witten- Rawlins Collection” is of particular interest for Cremona. The instruments will be not only on display in the Museo del Violino, but also will undergo a complete non-invasive sientific examination in the Arvedi Labsof the University of Pavia within the Museo del Violino. Antonio e Girolamo Amati- violino “The King Henry IV”, 1595 ca. (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Girolamo Amati- violino, 1609 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Girolamo Amati- violino piccolo, 1613 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Nicolò Amati- violino, 1628 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Antonio Stradivari- mandolino coristo “The Cutler- Channel”, 1680 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Antonio Stradivari- chitarra “The Rawlins”, 1700 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) attribuito alla bottega di Antonio Stradivari- archetto da violino, 1700 ca. (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Nicola Bergonzi- viola 1781 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Lorenzo Storioni- violino 1/2, 1793 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) . -

PART I Dramatis Personae

PART I Chapter 1 Dramatis Personae Antonio Stradivari (c16491-18th December 1737) Antonio Stradivari lived and worked in the Italian town of Cremona, south-east of Milan. His earliest violins date from the mid-1660s and follow the example of his Cremonese predecessor Nicolò Amati (1596-1684) in terms of size, proportion, and style.2 Between 1690 and 1700 Stradivari produced violins with sound-boxes which were slightly longer than the norm of 355mm, but this ‘Long Pattern’ style was apparently abandoned at the start of his ‘Golden Period’ – approximately 1700. During the subsequent two decades he produced well-proportioned instruments with gentle and low arching across the front and back plates, the scrolls being outlined with black pigment to emphasise the edges of the spirals, and the instruments varnished with what some have claimed to have been a unique mixture of ingredients.3 By this time Antonio was certainly being helped in his workshop by two of his sons, Francesco and Omobono, and Roger Hargrave has suggested that Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù also worked in the Stradivari workshop.4 Charles Beare has indicated that, after 1720, Carlo Bergonzi (1683-1747) also participated in making instruments under Stradivari’s direction;5 however, Tim Ingles has stated that ‘Bergonzi was probably working independently in the early 1720s’.6 After 1720 Antonio’s energy, manual dexterity, and eyesight diminished (by then he was approximately 70 years old) and instruments from his final years are less well finished, with a more pronounced arch across the body and a distinctively dark tone. Antonio apparently continued to work until his death in 1737. -

The Strad Magazine

FRESH THINKING WOOD DENSITOMETRY MATERIAL Were the old Cremonese luthiers really using better woods than those available to other makers FACTS in Europe? TERRY BORMAN and BEREND STOEL present a study of density that seems to suggest otherwise Violins await testing on a CT scanner gantry S ALL LUTHIERS ARE WELL AWARE, of Stradivari. To test this conjecture, we set out to compare the business of making an instrument of the the wood employed by the classical Cremonese makers with violin family is fraught with pitfalls. There that used by other makers, during the same time period but are countless ways to ruin the sound of the from various regions across Europe. This would eliminate one fi nished product, starting with possibly the variable – the ageing of the wood – and allow the tracking of Amost fundamental decision of all: what wood to use. In the past geographical and topographical variation. In particular, we 35 years we have seen our knowledge of the available options wanted to investigate the densities of the woods involved, which expand greatly – and as we learn more about the different wood we felt could be the key to unlocking these secrets. choices, it is increasingly hard not to agonise over the decision. What are the characteristics we need as makers? Should we just WHY DENSITY? look for a specifi c grain line spacing, or a good split? Those were The three key properties of wood, from an instrument maker’s the characteristics that makers were once taught to watch out perspective, are density, stiffness (‘Young’s modulus’) and for, and yet results are diffi cult to repeat from instrument to damping (in its simplest terms, a measure of how long an object instrument when using the same pattern – suggesting these are will vibrate after being set in motion). -

Amati's Dream

Teacher’s Guide Amati’s Dream for Narrator, Violin & String Orchestra Amati’s Dream takes place in Cremona, Italy in the year 1666. The apprentice Raphael is learning to make violins in the shop of Nicolò Amati. Raphael enjoys his work, but he secretly yearns to be a violinist. His family cannot afford an instrument or music lessons, so Raphael tries his best to be content with working in the violin shop. Will Raphael fulfill his dream? The story is multi-layered and thought provoking. The children are introduced to the fascinating and magical world of the violin through narration and music. The information in the story is woven into the narrative and very accessible. The music is melodic and easy to comprehend. www.atlantic-crossing.com !1 Nicolo Amati Nicolò Amati was born in 1596 and died in 1684. He was an Italian violin maker; they are also known as luthiers. Amati built instruments over 300 years ago by candlelight, and without electric tools. Today, his instruments are very rare and extremely valuable. Nicolò Amati lived in the time known as the Renaissance; the word means rebirth. It is the time between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries. The Renaissance was a time for the rebirth of science, education, music, art, and literature. The changes provided a better life for the people. Apprentice Raphael was an apprentice in the shop of Nicolò Amati. An apprentice trains for a craft or profession while working for an employer, as opposed to someone who learns by attending school. Often, the apprentice worked for his employer in exchange for lodging, food and training.