Italy's Primacy in Musical History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B&F Magazine Issue 31

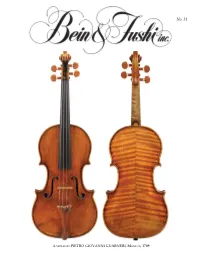

No. 31 A VIOLIN BY PIETRO GIOVANNI GUARNERI, MANTUA, 1709 superb instruments loaned to them by the Arrisons, gave spectacular performances and received standing ovations. Our profound thanks go to Karen and Clement Arrison for their dedication to preserving our classical music traditions and helping rising stars launch their careers over many years. Our feature is on page 11. Violinist William Hagen Wins Third Prize at the Queen Elisabeth International Dear Friends, Competition With a very productive summer coming to a close, I am Bravo to Bein & Fushi customer delighted to be able to tell you about a few of our recent and dear friend William Hagen for notable sales. The exquisite “Posselt, Philipp” Giuseppe being awarded third prize at the Guarneri del Gesù of 1732 is one of very few instruments Queen Elisabeth Competition in named after women: American virtuoso Ruth Posselt (1911- Belgium. He is the highest ranking 2007) and amateur violinist Renee Philipp of Rotterdam, American winner since 1980. who acquired the violin in 1918. And exceptional violins by Hagen was the second prize winner Camillo Camilli and Santo Serafin along with a marvelous of the Fritz Kreisler International viola bow by Dominique Peccatte are now in the very gifted Music Competition in 2014. He has hands of discerning artists. I am so proud of our sales staff’s Photo: Richard Busath attended the Colburn School where amazing ability to help musicians find their ideal match in an he studied with Robert Lipsett and Juilliardilli d wherehh he was instrument or bow. a student of Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho. -

A Violin by Giuseppe Giovanni Battista Guarneri

141 A VIOLIN BY GIUSEPPE GIOVANNI BATTISTA GUARNERI Roger Hargrave, who has also researched and drawn the enclosed poster, discusses an outstanding example of the work of a member of the Guarneri family known as `Joseph Guarneri filius Andrea'. Andrea Guarneri was the first He may never have many details of instruments by of the Guarneri family of violin reached the heights of his Joseph filius at this period recall makers and an apprentice of contemporary, the Amati school, this type of Nicola Amati (he was actually varnish, in combination with registered as living in the house Antonio Stradivarius, but he the freer hand of Joseph, gives of Nicola Amati in 1641). Andrea's does rank as one of the the instruments a visual impact youngest son, whose work is il - greatest makers of all time. never achieved by an Amati or , lustrated here, was called. We should not forget he with the exception of Stradi - Giuseppe. Because several of the sired and trained the great vari, by any other classical Guarneri family bear the same del Gesu' maker before this time. christian names, individuals have traditionally been identified by a It should be said, however, suffix attached to their names. that the varnish of Joseph filius Thus, Giuseppe's brother is known as `Peter Guarneri varies considerably. It is not always of such out - of Mantua' to distinguish him from Giuseppe's son, standing quality the same can be said of Joseph's pro - who is known as `Peter Guarneri of Venice'. duction in general. If I were asked to describe the instruments of a few of the great Cremonese makers Giuseppe himself is called 'Giuseppe Guarneri filius in a single word, I would say that Amatis (all of them) Andrea' or, more simply, `Joseph filius' to distinguish are `refined', Stradivaris are `stately', del Gesus are him from his other son, the illustrious 'Giuseppe `rebellious' and the instruments of Joseph filius An - Guarneri del Gesu'. -

Antonio Stradivari "Servais" 1701

32 ANTONIO STRADIVARI "SERVAIS" 1701 The renowned "Servais" cello by Stradivari is examined by Roger Hargrave Photographs: Stewart Pollens Research Assistance: Julie Reed Technical Assistance: Gary Sturm (Smithsonian Institute) In 184.6 an Englishman, James Smithson, gave the bines the grandeur of the pre‑1700 instrument with US Government $500,000 to be used `for the increase the more masculine build which we could wish to and diffusion of knowledge among men.' This was the have met with in the work of the master's earlier beginning of the vast institution which now domi - years. nates the down‑town Washington skyline. It includes the J.F. Kennedy Centre for Performing Arts and the Something of the cello's history is certainly worth National Zoo, as well as many specialist museums, de - repeating here, since, as is often the case, much of picting the achievements of men in every conceiv - this is only to be found in rare or expensive publica - able field. From the Pony Express to the Skylab tions. The following are extracts from the Reminis - orbital space station, from Sandro Botticelli to Jack - cences of a Fiddle Dealer by David Laurie, a Scottish son Pollock this must surely be the largest museum violin dealer, who was a contemporary of J.B. Vuil - and arts complex anywhere in the world. Looking laume: around, one cannot help feeling that this is the sort While attending one of M. Jansen's private con - of place where somebody might be disappointed not certs, I had the pleasure of meeting M. Servais of Hal, to find the odd Strad! And indeed, if you can manage one of the most renowned violoncellists of the day . -

Reconstructing Lost Instruments Praetorius’S Syntagma Musicum and the Violin Family C

Prejeto / received: 3. 5. 2019. Odobreno / accepted: 12. 9. 2019. doi: 10.3986/dmd15.1-2.07 RECONSTRUCTING LOST INSTRUMENTS Praetorius’S Syntagma musicum and the Violin Family C. 1619 Matthew Zeller Duke University Izvleček: Knjigi De organographia in Theatrum Abstract: Michael Praetorius’s De organographia instrumentorum Michaela Praetoriusa vsebujeta and Theatrum instrumentorum provide valuable dragocene namige, ki pomagajo pri poznavanju clues that contribute to a new understanding glasbil iz družine violin okoli leta 1619; številna of the violin family c. 1619, many surviving ex- preživela glasbila so manjša, kot so bili izvirniki amples of which are reduced in size from their v 16. in 17. stoletju. Podatki o preživelih glas- sixteenth- and seventeenth-century dimensions. bilih – predvsem izdelki družine Amati – skupaj The record of surviving instruments – especially z metrologijo, sekundarno dokumentacijo in those of the Amati family – alongside metrologic, ikonografskim gradivom kažejo na to, da je documentary and iconographic evidence shows Michael Praetorius opisal veliko glasbilo, po that Michael Praetorius describes a large in- velikosti izjemno podobno violončelu (basso strument conforming remarkably well to the da braccio),kar je odličen primer predstavitve original dimensions of the basso da braccio glasbila iz družine violin in točne uglasitve, kot (violoncello), as well as furnishing an excellent so jih poznali v času izida Praetoriusovega dela. scale representation of the violin family as it was at the time of these works’ -

Violin Detective

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS instruments have gone up in value after I found that their soundboards matched trees known to have been used by Stradivari; one subsequently sold at auction for more than four times its estimate. Many convincing for- KAMILA RATCLIFF geries were made in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but the science did not exist then. Forgers now are aware of dendro- chronology, and it could be a problem if they use wood from old chalets to build sophisti- cated copies of historical instruments. How about unintentional deceit? I never like to ‘kill’ a violin — reveal it as not what it seems. But if the wood does not match the claims, I investigate. I was recently sent photos of a violin supposedly made by an Italian craftsman who died in 1735. The wood dated to the 1760s, so I knew he could not have made it. But I did see strong cor- relations to instruments made by his sons and nephews who worked in the 1770s. So Peter Ratcliff restores and investigates violins from his workshop in Hove, UK. I deduced that the violin might have been damaged and an entirely new soundboard made after the craftsman’s death. The violin Q&A Peter Ratcliff was pulled from auction, but not before it had received bids of more than US$100,000. Will dendrochronology change the market? Violin detective I think it already has, and has called into Peter Ratcliff uses dendrochronology — tree-ring dating — to pin down the age and suggest the question some incorrect historical assump- provenance of stringed instruments. -

Stradivari Violin Manual

Table of Contents 1. Disclaimer .................................................................................................................. 1 2. Welcome .................................................................................................................... 2 3. Document Conventions ............................................................................................... 3 4. Installation and Setup ................................................................................................. 4 5. About STRADIVARI VIOLIN ........................................................................................ 6 5.1. Key Features .................................................................................................... 6 6. Main Page .................................................................................................................. 8 7. Snapshots ................................................................................................................ 10 7.1. Overview of Snapshots ................................................................................... 10 7.2. Saving a User Snapshot ................................................................................. 10 7.3. Loading a Snapshot ......................................................................................... 11 7.4. Deleting a User Snapshot ............................................................................... 12 8. Articulation .............................................................................................................. -

Reunion in Cremona

Reunion in Cremona Reunion in Cremona is the name of the exhibition that is taking place at the Museo del Violino from September 21 2019 and October 18 2020. It is a “reunion” indeed between historical instruments made by the great violinmakers of the past and their birthplace. Within important exhibition are displayed 8 masterpieces of cremonese classical violinmaking tradition and a bow attributed to the workshop of the famous Antonio Stradivari that the National Music Museum of Vermillion, South Dakota decided to house to the Museo del Violino during the renovation of its building and the expansion of the exhibiting areas. The NMM is one of the most important musical instruments museums in the world, with more than 15000 pieces divided into different collections. The “Witten- Rawlins Collection” is of particular interest for Cremona. The instruments will be not only on display in the Museo del Violino, but also will undergo a complete non-invasive sientific examination in the Arvedi Labsof the University of Pavia within the Museo del Violino. Antonio e Girolamo Amati- violino “The King Henry IV”, 1595 ca. (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Girolamo Amati- violino, 1609 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Girolamo Amati- violino piccolo, 1613 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Nicolò Amati- violino, 1628 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Antonio Stradivari- mandolino coristo “The Cutler- Channel”, 1680 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Antonio Stradivari- chitarra “The Rawlins”, 1700 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) attribuito alla bottega di Antonio Stradivari- archetto da violino, 1700 ca. (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Nicola Bergonzi- viola 1781 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) Lorenzo Storioni- violino 1/2, 1793 (National Music Museum, Vermillion- South Dakota) . -

PART I Dramatis Personae

PART I Chapter 1 Dramatis Personae Antonio Stradivari (c16491-18th December 1737) Antonio Stradivari lived and worked in the Italian town of Cremona, south-east of Milan. His earliest violins date from the mid-1660s and follow the example of his Cremonese predecessor Nicolò Amati (1596-1684) in terms of size, proportion, and style.2 Between 1690 and 1700 Stradivari produced violins with sound-boxes which were slightly longer than the norm of 355mm, but this ‘Long Pattern’ style was apparently abandoned at the start of his ‘Golden Period’ – approximately 1700. During the subsequent two decades he produced well-proportioned instruments with gentle and low arching across the front and back plates, the scrolls being outlined with black pigment to emphasise the edges of the spirals, and the instruments varnished with what some have claimed to have been a unique mixture of ingredients.3 By this time Antonio was certainly being helped in his workshop by two of his sons, Francesco and Omobono, and Roger Hargrave has suggested that Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù also worked in the Stradivari workshop.4 Charles Beare has indicated that, after 1720, Carlo Bergonzi (1683-1747) also participated in making instruments under Stradivari’s direction;5 however, Tim Ingles has stated that ‘Bergonzi was probably working independently in the early 1720s’.6 After 1720 Antonio’s energy, manual dexterity, and eyesight diminished (by then he was approximately 70 years old) and instruments from his final years are less well finished, with a more pronounced arch across the body and a distinctively dark tone. Antonio apparently continued to work until his death in 1737. -

Searching for Giuseppe Guarneri Del Gesù: a Paper-Chase and a Proposition

Searching for Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù: a paper-chase and a proposition Nicholas Sackman © 2021 During the past 200 years various investigators have laboured to unravel the strands of confusion which have surrounded the identity and life-story of the violin maker known as Bartolomeo Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù. Early-nineteenth-century commentators – Count Cozio di Salabue, for example – struggled to make sense of the situation through the physical evidence of the instruments they owned, the instruments’ internal labels, and the ‘understanding’ of contemporary restorers, dealers, and players; regrettably, misinformation was often passed from one writer to another, sometimes acquiring elaborations on the way. When research began into Cremonese archives the identity of individuals (together with their dates of birth and death) were sometimes announced as having been securely determined only for subsequent investigations to show that this certainty was illusory, the situation being further complicated by the Italian habit of christening a new- born son with multiple given names (frequently repeating those already given to close relatives) and then one or more of the given names apparently being unused during that new-born’s lifetime. During the early twentieth century misunderstandings were still frequent, and even today uncertainties still remain, with aspects of del Gesù’s chronology rendered opaque through contradictory or no documentation. The following account examines the documentary and physical evidence. ***** NB: During the first decades of the nineteenth century there existed violins with internal labels showing dates from the 1720s and the inscription Joseph Guarnerius Andrea Nepos. The Latin Dictionary compiled by Charlton T Lewis and Charles Short provides copious citations drawn from Classical Latin (as written and spoken during the period when the Roman Empire was at its peak, i.e. -

The History of the King Violincello Created by Andrea Amati(1505-1577)

May 2011 Volume 3 Magazine for Strings The History of The King Violincello created by Andrea Amati(1505-1577) YoYo Ma: Forging a Career in Music The Art of the Luthier The Music of Mozart, Become Inspired! The History of The King Violincello 2-10 created by Andrea Amati (1505-1577) Peggy Connor Forging a Career in Music 11-30 Inspiring advice from Yo Yo Ma The Art of the Luthier 31-35 Features A delicate art Harold Golden The Music of Mozart 36-45 Be inspired! Thomas Smith The Newest Juilllard Prodigy 46-57 Meet an amazing violinist Peggy Connor Priceless Violins of Cremona, Italy 58-63 A tour of the Museum of Cremona John Davis Suzuki Students 64-72 Observe how they learn Harold Golden Chicago Symphony Cellists 73-84 The newest generation John Davis The Latest Trends in the Music 85-94 A discussion with contemporary composers Eliza Jones Identifying a Young Prodigy 95-101 What defines truly gifted? Thomas Smith Orchestral Performance Schedules 102-105 May-Sept. Employment Opportunities 106-110 May 2011 May 2011 1 The History of The King Violincello Giuseppe (del Gesu) (1698-1744), Antonio Stradivari (1644-1737) Created by Andrea Amati, 1505-1577, Cremona, Italy of Cremona- and two of his sons, By Peggy Connor Francesco Stradivari (1671-1743) Omobono Stradivari (1679-1742), Jacob Stainer(1617-1683) of Absom The violin emerged from northern Italy Amati instruments that have survived. in Tyrol in the early 16th century, preceeded and One of oldest “surviving” dated violin, is Documented resident apprentices of the evolving from three likely fretted and non the “Charles IX” by Andrea Amati, made in Nicolo Amati workshop: fretted, stringed instruments: the rebec, the Cremona in1560. -

1002775354-Alcorn.Pdf

3119 A STUDY OF STYLE AND INFLUENCE IN THE EARLY SCHOOLS OF VIOLIN MAKING CIRCA 1540 TO CIRCA 1800 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Allison A. Alcorn, B.Mus. Denton, Texas December, 1987 Alcorn, Allison A., A Study of Style and Influence in the Ear School of Violin Making circa 1540 to circa 1800. Master of Music (Musicology), December 1987, 172 pp., 2 tables, 31 figures, bibliography, 52 titles. Chapter I of this thesis details contemporary historical views on the origins of the violin and its terminology. Chapters II through VI study the methodologies of makers from Italy, the Germanic Countries, the Low Countries, France, and England, and highlights the aspects of these methodologies that show influence from one maker to another. Chapter VII deals with matters of imitation, copying, violin forgery and the differences between these categories. Chapter VIII presents a discussion of the manner in which various violin experts identify the maker of a violin. It briefly discusses a new movement that questions the current methods of authenti- cation, proposing that the dual role of "expert/dealer" does not lend itself to sufficient objectivity. The conclusion suggests that dealers, experts, curators, and musicologists alike must return to placing the first emphasis on the tra- dition of the craft rather than on the individual maker. o Copyright by Allison A. Alcorn TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES.... ............. ........viii LIST OF TABLES. ................ ... x Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . .............. *.. 1 Problems in Descriptive Terminology 3 The Origin of the Violin....... -

Stradivari's 'Tuscan' Viola

53 Stradivari’s 'Tuscan' viola ROGER HARGRAVE ON A RARE SURVIVING VIOLA FROM STRADIVARI'S MOST SKILLFUL PERIOD AS A CRAFTSMAN, MADE FOR PRINCE FERDINAND, SON OF THE GRAND DUKE OF TUSCANY. From documentary evidence we know that Stradi - illustrated here. Like the large tenor previously vari made more violas than those which have sur - mentioned, this viola, along with a violin and a cello, vived but we have no idea how many. Neither do we was delivered to Prince Ferdinand, son of the Grand seem to know how many still exist today. Duke of Tuscany, Cosimo III de Medici in Florence, in the autumn of 1690. All of these instruments are Estimates range from 10 to 18; you can take your known either as the `Tuscan' or the 'Medici' or some - pick. From the surviving relics of Stradivari's work - times even the `Tuscan Medici'. shop we can deduce that he made at least three types of viola form. The largest of these was the tenor form Stradivari's 1690s contralto viola mould was to do of which the good service He does not seem to have re designed the contralto after this date, and apparently even the most striking example is the viola housed in the last known Stradivari viola, the 'Gibson' 1734, was Instituto Cherubim in Florence (a notoriously diffi - constructed on this mould (see STRAD poster, Sep - cult museum to get into). The body length of this tember 1986). Any variations in the lengths and viola is 475mm or 18 3/4". (There must be a viola joke widths of the contraltos between 1690 and 1734 can there somewhere).