Stowell Make-Up

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

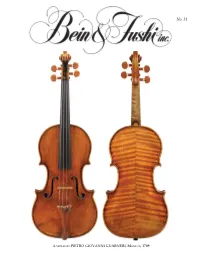

B&F Magazine Issue 31

No. 31 A VIOLIN BY PIETRO GIOVANNI GUARNERI, MANTUA, 1709 superb instruments loaned to them by the Arrisons, gave spectacular performances and received standing ovations. Our profound thanks go to Karen and Clement Arrison for their dedication to preserving our classical music traditions and helping rising stars launch their careers over many years. Our feature is on page 11. Violinist William Hagen Wins Third Prize at the Queen Elisabeth International Dear Friends, Competition With a very productive summer coming to a close, I am Bravo to Bein & Fushi customer delighted to be able to tell you about a few of our recent and dear friend William Hagen for notable sales. The exquisite “Posselt, Philipp” Giuseppe being awarded third prize at the Guarneri del Gesù of 1732 is one of very few instruments Queen Elisabeth Competition in named after women: American virtuoso Ruth Posselt (1911- Belgium. He is the highest ranking 2007) and amateur violinist Renee Philipp of Rotterdam, American winner since 1980. who acquired the violin in 1918. And exceptional violins by Hagen was the second prize winner Camillo Camilli and Santo Serafin along with a marvelous of the Fritz Kreisler International viola bow by Dominique Peccatte are now in the very gifted Music Competition in 2014. He has hands of discerning artists. I am so proud of our sales staff’s Photo: Richard Busath attended the Colburn School where amazing ability to help musicians find their ideal match in an he studied with Robert Lipsett and Juilliardilli d wherehh he was instrument or bow. a student of Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho. -

A Violin by Giuseppe Giovanni Battista Guarneri

141 A VIOLIN BY GIUSEPPE GIOVANNI BATTISTA GUARNERI Roger Hargrave, who has also researched and drawn the enclosed poster, discusses an outstanding example of the work of a member of the Guarneri family known as `Joseph Guarneri filius Andrea'. Andrea Guarneri was the first He may never have many details of instruments by of the Guarneri family of violin reached the heights of his Joseph filius at this period recall makers and an apprentice of contemporary, the Amati school, this type of Nicola Amati (he was actually varnish, in combination with registered as living in the house Antonio Stradivarius, but he the freer hand of Joseph, gives of Nicola Amati in 1641). Andrea's does rank as one of the the instruments a visual impact youngest son, whose work is il - greatest makers of all time. never achieved by an Amati or , lustrated here, was called. We should not forget he with the exception of Stradi - Giuseppe. Because several of the sired and trained the great vari, by any other classical Guarneri family bear the same del Gesu' maker before this time. christian names, individuals have traditionally been identified by a It should be said, however, suffix attached to their names. that the varnish of Joseph filius Thus, Giuseppe's brother is known as `Peter Guarneri varies considerably. It is not always of such out - of Mantua' to distinguish him from Giuseppe's son, standing quality the same can be said of Joseph's pro - who is known as `Peter Guarneri of Venice'. duction in general. If I were asked to describe the instruments of a few of the great Cremonese makers Giuseppe himself is called 'Giuseppe Guarneri filius in a single word, I would say that Amatis (all of them) Andrea' or, more simply, `Joseph filius' to distinguish are `refined', Stradivaris are `stately', del Gesus are him from his other son, the illustrious 'Giuseppe `rebellious' and the instruments of Joseph filius An - Guarneri del Gesu'. -

„Ich Für Meinen Theil Liebe Von Herzen Den Peters… Aber Der Verleger Soll Mich in Ruhe Laßen.“

Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Institut für Musikwissenschaft und Musikpädagogik Musikwissenschaftliches Seminar Examensmodul Bachelorarbeit Erstprüfer: Dr. Peter Schmitz Zweitprüfer: Prof. Dr. Jürgen Heidrich „Ich für meinen theil liebe von Herzen den Peters… Aber der Verleger soll mich in ruhe laßen.“ Edition der Briefe des Cellisten und Komponisten Bernhard Romberg an seinen Verleger Carl Friedrich Peters (1815–1827) Maike Thiemann 2-Fach Bachelor Musikwissenschaft/ Germanistik Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung ...................................................................................................... 3 2. Briefe von Bernhard Romberg an seinen Verleger Carl Friedrich Peters (1816 - 1827) .................................................................................................... 11 3. Schlussbetrachtung ................................................................................. 163 4. Register ......................................................................................................169 4.1 Personenregister…………………………………………………………….169 4.2 Auszug Stammbaum Familie Romberg/ Familie Peters ........................ 179 4.3 Werkregister ......................................................................................... 180 4.4 Währungen ........................................................................................... 183 4.5 Quellenverzeichnis ................................................................................ 185 5. Anhang ..................................................................................................... -

Die Sammlung Historischer Streichinstrumente Der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank

OESTERREICHISCHE NATIONALBANK EUROSYSTEM Die Sammlung historischer Streichinstrumente der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank The collection of Historical String Instruments of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank Inhaltsverzeichnis Contents Impressum Medieninhaberin: Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Otto-Wagner-Platz 3, 1090 Wien, T: (+43 1) 404 20-6605, F: (+43 1) 404 20-6697, www.oenb.at Redaktion: Mag. Brigitte Alizadeh-Gruber, Muna Kadum, Martina Leitner, Mag. Irene Mühldorf Grafik, Layout und Satz: Melanie Schuhmacher Fotos: © Graphisches Atelier Neumann, Wien Druck: Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Abteilung für Öffentlichkeitsarbeit und Publikationen, Gruppe Multimedia-, Internet- und Print-Service. © Oesterreichische Nationalbank, 2013. Streichinstrumente/ String Instruments 9 Amati Andrea 10 Violoncello, Cremona, spätes 16. Jh. 10 Bergonzi Carlo 12 Violine, Cremona 1723 12 Violine, Cremona nach 1724 14 Bergonzi Michelangelo 16 Violine, Cremona um 1740 16 Violine, „ex Hamma-Segelman“, Cremona um 1750 18 Camilli Camillus 20 Violine, Mantua 1736 20 Ceruti Giovanni Battista 22 Viola, Cremona um 1810 22 Gagliano Alessandro 24 Violoncello, Neapel ca. 1710 24 Grancino Giovanni 26 Violoncello, „ex Piatti“ – „ex Dunlop“, Mailand 1706 26 Guadagnini Giovanni Battista 28 Violoncello, „ex von Zweygberg“, Piacenza 174. 28 Violine, Mailand 1749 30 Violine, „ex Meinel“, Turin um 1770–1775 32 Violine, Turin 1772 34 Violine, „Mantegazza“, Turin 1774 36 Violine, Turin 177. 38 Viola, Turin 1784 40 Guarneri Andrea 42 Violine, Cremona, Mitte 17. Jh. 42 Guarneri del Gesù Giuseppe 44 Violine, „ex Sorkin“, Cremona 1731 44 Violine, „ex Guilet“, Cremona nach 1732 46 Violine, „ex Carrodus“, Cremona 1741 48 Lorenzini Gaspare 50 Violine, Piacenza um 1760 50 Maggini Giovanni Paolo 52 Viola, Brescia, frühes 17. Jh. 52 Montagnana Domenico 54 Violine, Venedig 1727 54 Seraphin Sanctus 56 Violine, Venedig 1733 56 Violine, „ex Hamma“, Venedig nach 1748 58 Silvestre Pierre 60 Violine, „ex Moser“, Lyon ca. -

Importance and Pedagogical Value of Three Sonatas for Two Cellos, Op

PLACZEK, ROMAN, D.M.A. Importance and Pedagogical Value of Three Sonatas for Two Cellos, Op. 43 by Bernhard Romberg (2014). Directed by Dr. Alexander Ezerman. 127 pp. The Three Sonatas for Two Cellos, Op. 43 by Bernhard Heinrich Romberg were composed as a progressive performance work. The most widely used copy of the work is a C. F. Peters, Leipzig Edition edited by Friedrich Wilhelm Grützmacher. In this edition, the Sonatas are exhaustively marked with fingerings, alternate fingering, dynamics, dynamic changes, glissandi, bowings, bowstrokes and bow placement, accents, tempo changes, moods, and articulations. The combination of Romberg's melodic and pedagogically thought-through compositions and Grützmacher's expert editorial work results in invaluable pedagogical and performance work. Each subsequent sonata presents bigger challenge for a player while each preceding one also serves as a training tool for successful mastering of the following one. The Opus 43 is a set of individually viable sonatas that can stand independently and still serve as useful learning material. Grützmacher's respect for Romberg's style and his clear vision of pedagogical benefits are reflected in logical sequence of fingering and bowing challenges presented in each Sonata. Precise and complete performance markings serve as an essential guiding tool navigating a player towards a successful performance. If learned and performed as a set, the Three Sonatas for Two Cellos, Op. 43 by Bernard Heinrich Romberg are an excellent progressive performance work of the advanced level. 1 The purpose of this analysis is to revive and highlight the importance of Romberg’s compositions and Grützmacher’s editorial effort and the pedagogical value of a direct teacher-student interaction the Three Sonatas for Two Cellos, Opus 43 represent. -

Correcting the Right Hand Bow Position for the Student Violinist and Violist Matson Alan Topper

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2002 Correcting the Right Hand Bow Position for the Student Violinist and Violist Matson Alan Topper Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC CORRECTING THE RIGHT HAND BOW POSITION FOR THE STUDENT VIOLINIST AND VIOLIST By Matson Alan Topper A Treatise submitted to the School of Music In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2002 Copyright © 2002 Matson Alan Topper All rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the treatise of Matson Alan Topper defended on 30 October 2002. Eliot Chapo Professor Directing Treatise Ladislav Kubik Outside Committee Member Phillip Spurgeon Committee Member Lubomir Georgiev Committee Member To The Memory of My Teacher Tadeusz Wroński iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It was Tadeusz Wroński whose inspiration laid the foundation for this treatise. The desire of writing about the bow and its significance in successful violin playing followed. Today, I wish to thank professor Wroński for teaching me the fundamentals of correct violin playing. I was privileged to see him at his home in Poland (1999) and discuss my subject. We both celebrated the “pupil returning to the master,” which occurred a few months before Professor Wroński passed away. Grateful acknowledgement is extended to Eliot Chapo, my advisor and violin professor during the doctoral work at the Florida State University; colleague, concert artist, and friend, for both his musical critiques and expertise provided during our interview sessions which have found a substantial content in this subject. -

Dirk Brossé Cello Concerto for Isabelle Marie Hallynck London

Dirk Brossé Cello Concerto for Isabelle Marie Hallynck London Symphony Orchestra Dirk Brossé §2016 Dirk Brossé, under exclusive license to Warner Music Benelux NV-SA, a Warner Music Group Company ©2016 Warner Music Benelux NV-SA. All rights reserved. Printed in EU. Marketed and distributed by Warner Music Benelux. MCPS/Biem 5054197257650 PAG. 02 PAG. 03 The Cello Concerto for Isabelle Dirk Brossé was commissioned by Pierre Drion and is dedicated to Isabelle Schuiling Cello Concerto for Isabelle __________ ... when love becomes an instinct ... Marie Hallynck is playing a Matteo Goffriller, 1717 The documentary ‘The Making Of’ by Jacques Servaes 1 Part 1 Flirting (9:33) can be viewed on Youtube.com/DirkBrosse 2 Part 2 Unrequited Love (9:13) French and Dutch booklet texts available on www.dirkbrosse.be 3 Part 3 Butterfly Belly Waltz (5:51) Many thanks to Nicolas, Julian, Stephen, Maggie, Jake, Adam, Fiona, Aline, Bastien, Luk, Emily, Luk, Piet, Brigitte 4 Part 4 Spiritual Love (10:51) 5 Part 5 Me, myself and I (7:15) Engineer: Jake Jackson Assistant engineer: Adam Miller 9 Part 6 Fatal Attraction (5:20) Editor / assistant engineer: Fiona Cruickshank Additional editing: Aline Blondiau 7 Part 7 Romantic Love (6:00) Additional mix: Bastien Gilson Recording coordination: Maggie Rodford & Emily Appleton Holley Marie Hallynck, cello Mastering: Bastien Gilson London Symphony Orchestra Producer: Luk Vaes Dirk Brossé, conductor Artist photos: Luk Monsaert Carmine Lauri, concertmaster Graphic design: Piet De Ridder Translations: Stephen Smith Recorded at Air Lyndhurst Studio London, on 1-2 September 2015 Executive producer: Brigitte Ghyselen Edited at Air Lyndhurst Studio, London PAG. -

A Prima Vista

A PRIMA VISTA a survey of reprints and of recent publications 2002/1 BROEKMANS & VAN POPPEL Van Baerlestraat 92-94 Postbus 75228 1070 AE AMSTERDAM sheet music: 020-6796575 CDs: 020-6751653/fax: 020-6646759 also on INTERNET: www.broekmans.com e-mail: [email protected] 2 CONTENTS A PRIMA VISTA 2002/1 PAGE HEADING 03 PIANO 2-HANDS 07 PIANO 4-HANDS, 2 AND MORE PIANOS, HARPSICHORD 08 ORGAN 09 KEYBOARD 1 STRING INSTRUMENT WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 10 VIOLIN SOLO, VIOLA SOLO 1 STRING INSTRUMENT WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, piano unless stated otherwise: 11 VIOLIN WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 12 VIOLIN PLAY-ALONG 13 VIOLA WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, CELLO WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 14 VIOLA DA GAMBA WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 14 2 AND MORE STRING INSTRUMENTS WITH AND WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 1 WIND INSTRUMENT WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 18 FLUTE SOLO, OBOE SOLO 19 CLARINET SOLO, SAXOPHONE SOLO, BASSOON SOLO, TRUMPET SOLO 20 HORN SOLO, TROMBONE SOLO, TUBA SOLO 1 WIND INSTRUMENT WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, piano unless stated otherwise: 20 PICCOLO WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, FLUTE WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 22 FLUTE PLAY-ALONG, ALTO FLUTE WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 23 OBOE WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, OBOE PLAY-ALONG, CLARINET WIT ACCOMPANIMENT 24 CLARINET PLAY-ALONG 25 BASSETHORN WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, SAXOPHONE WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 27 SAXOPHONE PLAY-ALONG 28 BASSOON WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, TRUMPET WIT ACCOMPANIMENT 29 TRUMPET PLAY-ALONG, HORN WITH ACCOMPANIMENT 30 TROMBONE WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, TROMBONE PLAY-ALONG 31 TUBA WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, EUPHONIUM PLAY-ALONG 2 AND MORE WIND INSTRUMENTS WITH AND WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 31 2 AND MORE WOODWIND -

The Working Methods of Guarneri Del Gesů and Their Influence Upon His

45 The Working Methods of Guarneri del Gesù and their Influence upon his Stylistic Development Text and Illustrations by Roger Graham Hargrave Please take time to read this warning! Although the greatest care has been taken while compiling this site it almost certainly contains many mistakes. As such its contents should be treated with extreme caution. Neither I nor my fellow contributors can accept responsibility for any losses resulting from information or opin - ions, new or old, which are reproduced here. Some of the ideas and information have already been superseded by subsequent research and de - velopment. (I have attempted to included a bibliography for further information on such pieces) In spite of this I believe that these articles are still of considerable use. For copyright or other practical reasons it has not been possible to reproduce all the illustrations. I have included the text for the series of posters that I created for the Strad magazine. While these posters are all still available, with one exception, they have been reproduced without the original accompanying text. The Labels mentions an early form of Del Gesù label, 98 later re - jected by the Hills as spurious. 99 The strongest evi - Before closing the body of the instrument, Del dence for its existence is found in the earlier Gesù fixed his label on the inside of the back, beneath notebooks of Count Cozio Di Salabue, who mentions the bass soundhole and roughly parallel to the centre four violins by the younger Giuseppe, all labelled and line. The labels which remain in their original posi - dated, from the period 1727 to 1730. -

The Rise and Fall of the Cellist-Composer of the Nineteenth Century

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 The Rise and Fall of the Cellist- Composer of the Nineteenth Century: A Comprehensive Study of the Life and Works of Georg Goltermann Including A Complete Catalog of His Cello Compositions Katherine Ann Geeseman Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC THE RISE AND FALL OF THE CELLIST-COMPOSER OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY: A COMPREHENSIVE STUDY OF THE LIFE AND WORKS OF GEORG GOLTERMANN INCLUDING A COMPLETE CATALOG OF HIS CELLO COMPOSITIONS By KATHERINE ANN GEESEMAN A treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2011 Katherine Geeeseman defended this treatise on October 20th, 2011. The members of the supervisory committee were: Gregory Sauer Professor Directing Treatise Evan Jones University Representative Alexander Jiménez Committee Member Corinne Stillwell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To my dad iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This treatise would not have been possible without the gracious support of my family, colleagues and professors. I would like to thank Gregory Sauer for his support as a teacher and mentor over our many years working together. I would also like to thank Dr. Alexander Jiménez for his faith, encouragement and guidance. Without the support of these professors and others such as Dr. -

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Through Brahms the ninth season July 22–August 13, 2011 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 Through Brahms Program Overview 6 Essay: “Johannes Brahms: The Great Romantic” by Calum MacDonald 8 Encounters I–IV 11 Concert Programs I–VI 30 String Quartet Programs 37 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 50 Chamber Music Institute 52 Prelude Performances 61 Koret Young Performers Concerts 64 Café Conversations 65 Master Classes 66 Open House 67 2011 Visual Artist: John Morra 68 Listening Room 69 Music@Menlo LIVE 70 2011–2012 Winter Series 72 Artist and Faculty Biographies 85 Internship Program 86 Glossary 88 Join Music@Menlo 92 Acknowledgments 95 Ticket and Performance Information 96 Calendar Cover artwork: Mertz No. 12, 2009, by John Morra. Inside (p. 67): Paintings by John Morra. Photograph of Johannes Brahms in his studio (p. 1): © The Art Archive/Museum der Stadt Wien/ Alfredo Dagli Orti. Photograph of the grave of Johannes Brahms in the Zentralfriedhof (central cemetery), Vienna, Austria (p. 5): © Chris Stock/Lebrecht Music and Arts. Photograph of Brahms (p. 7): Courtesy of Eugene Drucker in memory of Ernest Drucker. Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 69) and Ani Kavafian (p. 75): Christian Steiner. Paul Appleby (p. 72): Ken Howard. Carey Bell (p. 73): Steve Savage. Sasha Cooke (p. 74): Nick Granito. -

The BEST $500 VIOLIN

Serving All Levels Of Players The SHAR Connection Just Starting A Global Network Have questions about instruments? SHAR’s purchasing agents are string players, and they Only Musicians Answer the phone at travel the globe to work directly with our partner SHAR 800.248.7427 workshops. For nearly 50 years we have established longstanding relationships with the world’s leading makers and workshops in America, Europe, and Asia. How can I tell the quality of my student violin? Of course, a violin must sound good in order to From the wood selection to the acoustic models motivate your young student. But a high quality used, from the neck shapes to the various varnish instrument must also have easy-turning pegs that stay properties, our purchasing agents work with our in tune. The bridge, fingerboard, nut and soundpost partners to ensure that every detail is crafted to our must be carefully shaped and fit so that the violin is specifications. Our world-wide logistics network also easy to play and feels good to the hand. guarantees that our instruments and bows arrive here in Ann Arbor in ideal, safe condition. What makes one violin more expensive than another? The two biggest factors are the quality and age of the wood and the skill of the makers. Only a skilled maker is able to make all the parts fit together The SHAR Setup properly so the violin will work perfectly. Where Millimeters Count What size violin does my child need? That is best answered by the child’s teacher. The musicians who SHAR’s own Setup Shop, Restoration and Repair answer the phone at SHAR are well qualified to make department, staffed by experienced luthiers and a recommendation based on your child’s age and arm technicians, ensures each instrument is in healthy, length, but there’s no substitute for having a good stable condition and adjusted for optimal tonal response.