Almanacco 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B&F Magazine Issue 31

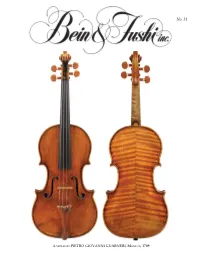

No. 31 A VIOLIN BY PIETRO GIOVANNI GUARNERI, MANTUA, 1709 superb instruments loaned to them by the Arrisons, gave spectacular performances and received standing ovations. Our profound thanks go to Karen and Clement Arrison for their dedication to preserving our classical music traditions and helping rising stars launch their careers over many years. Our feature is on page 11. Violinist William Hagen Wins Third Prize at the Queen Elisabeth International Dear Friends, Competition With a very productive summer coming to a close, I am Bravo to Bein & Fushi customer delighted to be able to tell you about a few of our recent and dear friend William Hagen for notable sales. The exquisite “Posselt, Philipp” Giuseppe being awarded third prize at the Guarneri del Gesù of 1732 is one of very few instruments Queen Elisabeth Competition in named after women: American virtuoso Ruth Posselt (1911- Belgium. He is the highest ranking 2007) and amateur violinist Renee Philipp of Rotterdam, American winner since 1980. who acquired the violin in 1918. And exceptional violins by Hagen was the second prize winner Camillo Camilli and Santo Serafin along with a marvelous of the Fritz Kreisler International viola bow by Dominique Peccatte are now in the very gifted Music Competition in 2014. He has hands of discerning artists. I am so proud of our sales staff’s Photo: Richard Busath attended the Colburn School where amazing ability to help musicians find their ideal match in an he studied with Robert Lipsett and Juilliardilli d wherehh he was instrument or bow. a student of Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho. -

Die Sammlung Historischer Streichinstrumente Der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank

OESTERREICHISCHE NATIONALBANK EUROSYSTEM Die Sammlung historischer Streichinstrumente der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank The collection of Historical String Instruments of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank Inhaltsverzeichnis Contents Impressum Medieninhaberin: Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Otto-Wagner-Platz 3, 1090 Wien, T: (+43 1) 404 20-6605, F: (+43 1) 404 20-6697, www.oenb.at Redaktion: Mag. Brigitte Alizadeh-Gruber, Muna Kadum, Martina Leitner, Mag. Irene Mühldorf Grafik, Layout und Satz: Melanie Schuhmacher Fotos: © Graphisches Atelier Neumann, Wien Druck: Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Abteilung für Öffentlichkeitsarbeit und Publikationen, Gruppe Multimedia-, Internet- und Print-Service. © Oesterreichische Nationalbank, 2013. Streichinstrumente/ String Instruments 9 Amati Andrea 10 Violoncello, Cremona, spätes 16. Jh. 10 Bergonzi Carlo 12 Violine, Cremona 1723 12 Violine, Cremona nach 1724 14 Bergonzi Michelangelo 16 Violine, Cremona um 1740 16 Violine, „ex Hamma-Segelman“, Cremona um 1750 18 Camilli Camillus 20 Violine, Mantua 1736 20 Ceruti Giovanni Battista 22 Viola, Cremona um 1810 22 Gagliano Alessandro 24 Violoncello, Neapel ca. 1710 24 Grancino Giovanni 26 Violoncello, „ex Piatti“ – „ex Dunlop“, Mailand 1706 26 Guadagnini Giovanni Battista 28 Violoncello, „ex von Zweygberg“, Piacenza 174. 28 Violine, Mailand 1749 30 Violine, „ex Meinel“, Turin um 1770–1775 32 Violine, Turin 1772 34 Violine, „Mantegazza“, Turin 1774 36 Violine, Turin 177. 38 Viola, Turin 1784 40 Guarneri Andrea 42 Violine, Cremona, Mitte 17. Jh. 42 Guarneri del Gesù Giuseppe 44 Violine, „ex Sorkin“, Cremona 1731 44 Violine, „ex Guilet“, Cremona nach 1732 46 Violine, „ex Carrodus“, Cremona 1741 48 Lorenzini Gaspare 50 Violine, Piacenza um 1760 50 Maggini Giovanni Paolo 52 Viola, Brescia, frühes 17. Jh. 52 Montagnana Domenico 54 Violine, Venedig 1727 54 Seraphin Sanctus 56 Violine, Venedig 1733 56 Violine, „ex Hamma“, Venedig nach 1748 58 Silvestre Pierre 60 Violine, „ex Moser“, Lyon ca. -

Reconstructing Lost Instruments Praetorius’S Syntagma Musicum and the Violin Family C

Prejeto / received: 3. 5. 2019. Odobreno / accepted: 12. 9. 2019. doi: 10.3986/dmd15.1-2.07 RECONSTRUCTING LOST INSTRUMENTS Praetorius’S Syntagma musicum and the Violin Family C. 1619 Matthew Zeller Duke University Izvleček: Knjigi De organographia in Theatrum Abstract: Michael Praetorius’s De organographia instrumentorum Michaela Praetoriusa vsebujeta and Theatrum instrumentorum provide valuable dragocene namige, ki pomagajo pri poznavanju clues that contribute to a new understanding glasbil iz družine violin okoli leta 1619; številna of the violin family c. 1619, many surviving ex- preživela glasbila so manjša, kot so bili izvirniki amples of which are reduced in size from their v 16. in 17. stoletju. Podatki o preživelih glas- sixteenth- and seventeenth-century dimensions. bilih – predvsem izdelki družine Amati – skupaj The record of surviving instruments – especially z metrologijo, sekundarno dokumentacijo in those of the Amati family – alongside metrologic, ikonografskim gradivom kažejo na to, da je documentary and iconographic evidence shows Michael Praetorius opisal veliko glasbilo, po that Michael Praetorius describes a large in- velikosti izjemno podobno violončelu (basso strument conforming remarkably well to the da braccio),kar je odličen primer predstavitve original dimensions of the basso da braccio glasbila iz družine violin in točne uglasitve, kot (violoncello), as well as furnishing an excellent so jih poznali v času izida Praetoriusovega dela. scale representation of the violin family as it was at the time of these works’ -

The Working Methods of Guarneri Del Gesů and Their Influence Upon His

45 The Working Methods of Guarneri del Gesù and their Influence upon his Stylistic Development Text and Illustrations by Roger Graham Hargrave Please take time to read this warning! Although the greatest care has been taken while compiling this site it almost certainly contains many mistakes. As such its contents should be treated with extreme caution. Neither I nor my fellow contributors can accept responsibility for any losses resulting from information or opin - ions, new or old, which are reproduced here. Some of the ideas and information have already been superseded by subsequent research and de - velopment. (I have attempted to included a bibliography for further information on such pieces) In spite of this I believe that these articles are still of considerable use. For copyright or other practical reasons it has not been possible to reproduce all the illustrations. I have included the text for the series of posters that I created for the Strad magazine. While these posters are all still available, with one exception, they have been reproduced without the original accompanying text. The Labels mentions an early form of Del Gesù label, 98 later re - jected by the Hills as spurious. 99 The strongest evi - Before closing the body of the instrument, Del dence for its existence is found in the earlier Gesù fixed his label on the inside of the back, beneath notebooks of Count Cozio Di Salabue, who mentions the bass soundhole and roughly parallel to the centre four violins by the younger Giuseppe, all labelled and line. The labels which remain in their original posi - dated, from the period 1727 to 1730. -

The Strad Magazine

FRESH THINKING WOOD DENSITOMETRY MATERIAL Were the old Cremonese luthiers really using better woods than those available to other makers FACTS in Europe? TERRY BORMAN and BEREND STOEL present a study of density that seems to suggest otherwise Violins await testing on a CT scanner gantry S ALL LUTHIERS ARE WELL AWARE, of Stradivari. To test this conjecture, we set out to compare the business of making an instrument of the the wood employed by the classical Cremonese makers with violin family is fraught with pitfalls. There that used by other makers, during the same time period but are countless ways to ruin the sound of the from various regions across Europe. This would eliminate one fi nished product, starting with possibly the variable – the ageing of the wood – and allow the tracking of Amost fundamental decision of all: what wood to use. In the past geographical and topographical variation. In particular, we 35 years we have seen our knowledge of the available options wanted to investigate the densities of the woods involved, which expand greatly – and as we learn more about the different wood we felt could be the key to unlocking these secrets. choices, it is increasingly hard not to agonise over the decision. What are the characteristics we need as makers? Should we just WHY DENSITY? look for a specifi c grain line spacing, or a good split? Those were The three key properties of wood, from an instrument maker’s the characteristics that makers were once taught to watch out perspective, are density, stiffness (‘Young’s modulus’) and for, and yet results are diffi cult to repeat from instrument to damping (in its simplest terms, a measure of how long an object instrument when using the same pattern – suggesting these are will vibrate after being set in motion). -

The History of the King Violincello Created by Andrea Amati(1505-1577)

May 2011 Volume 3 Magazine for Strings The History of The King Violincello created by Andrea Amati(1505-1577) YoYo Ma: Forging a Career in Music The Art of the Luthier The Music of Mozart, Become Inspired! The History of The King Violincello 2-10 created by Andrea Amati (1505-1577) Peggy Connor Forging a Career in Music 11-30 Inspiring advice from Yo Yo Ma The Art of the Luthier 31-35 Features A delicate art Harold Golden The Music of Mozart 36-45 Be inspired! Thomas Smith The Newest Juilllard Prodigy 46-57 Meet an amazing violinist Peggy Connor Priceless Violins of Cremona, Italy 58-63 A tour of the Museum of Cremona John Davis Suzuki Students 64-72 Observe how they learn Harold Golden Chicago Symphony Cellists 73-84 The newest generation John Davis The Latest Trends in the Music 85-94 A discussion with contemporary composers Eliza Jones Identifying a Young Prodigy 95-101 What defines truly gifted? Thomas Smith Orchestral Performance Schedules 102-105 May-Sept. Employment Opportunities 106-110 May 2011 May 2011 1 The History of The King Violincello Giuseppe (del Gesu) (1698-1744), Antonio Stradivari (1644-1737) Created by Andrea Amati, 1505-1577, Cremona, Italy of Cremona- and two of his sons, By Peggy Connor Francesco Stradivari (1671-1743) Omobono Stradivari (1679-1742), Jacob Stainer(1617-1683) of Absom The violin emerged from northern Italy Amati instruments that have survived. in Tyrol in the early 16th century, preceeded and One of oldest “surviving” dated violin, is Documented resident apprentices of the evolving from three likely fretted and non the “Charles IX” by Andrea Amati, made in Nicolo Amati workshop: fretted, stringed instruments: the rebec, the Cremona in1560. -

1002775354-Alcorn.Pdf

3119 A STUDY OF STYLE AND INFLUENCE IN THE EARLY SCHOOLS OF VIOLIN MAKING CIRCA 1540 TO CIRCA 1800 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Allison A. Alcorn, B.Mus. Denton, Texas December, 1987 Alcorn, Allison A., A Study of Style and Influence in the Ear School of Violin Making circa 1540 to circa 1800. Master of Music (Musicology), December 1987, 172 pp., 2 tables, 31 figures, bibliography, 52 titles. Chapter I of this thesis details contemporary historical views on the origins of the violin and its terminology. Chapters II through VI study the methodologies of makers from Italy, the Germanic Countries, the Low Countries, France, and England, and highlights the aspects of these methodologies that show influence from one maker to another. Chapter VII deals with matters of imitation, copying, violin forgery and the differences between these categories. Chapter VIII presents a discussion of the manner in which various violin experts identify the maker of a violin. It briefly discusses a new movement that questions the current methods of authenti- cation, proposing that the dual role of "expert/dealer" does not lend itself to sufficient objectivity. The conclusion suggests that dealers, experts, curators, and musicologists alike must return to placing the first emphasis on the tra- dition of the craft rather than on the individual maker. o Copyright by Allison A. Alcorn TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES.... ............. ........viii LIST OF TABLES. ................ ... x Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . .............. *.. 1 Problems in Descriptive Terminology 3 The Origin of the Violin....... -

Old Violins and VIOLIN LORE

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY From the library of Dr. Ernest Bueding MUSIC II Hill mil nil 3 1924 063 24 46^ Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924063241461 OLD VIOLINS PAGANINI. From the worlt of IJie aiiist, Ingres. Old Violins AND VIOLIN LORE BY Rev. H. R. HAWEIS. WITH 13 PLATES. LONDON WILLIAM REEVES Published by William Reeves Bookseller Ltd., la Norbury Crescent, London, S.W.16. Copyright. All Rights Reserved. Printed in England by Lowe &• Brydone (Printers) Ltd., London, N.W.IO. CONTENTS CHAP. FAQB PRELUDE 7 I. VIOLIN GENESIS 15 IL VIOLIN CONSTITUTION .... 22 III. VIOLINS AT BRESCIA 30 IV. VIOLINS AT CREMONA .... 42 V. VIOLINS AT CREMONA {eontinned) . 60 VI. VIOLINS IN GERMANY .... 91 Vn. VIOLINS IN FRANCE 104 VIIL VIOLINS IN ENGLAND 118 IX. VIOLIN VARNISH 146 X. VIOLIN STRINGS 153 XI. VIOLIN BOWS 161 XII. VIOLIN TARISIO 171 XIIL VIOLINS AT MIRECOURT, MITTEN- WALD, AND MARKNEUKIRCHEN . 186 XIV. VIOLIN TREATMENT 198 XV. VIOLIN DEALERS, COLLECTORS, AND AMATEURS 214 POSTLUDE 241 DICTIONARY OF VIOLIN MAKERS . .243 BIBLIOGRAPHY 285 DESCRIPTION OF PLATES 237 V — OLD VIOLINS PRELUDE What is the secret of the violin? Why is it that when a gi'eat violinist appears all the other soloists have to take a back seat ? The answer is : the fascination of the violin is the fascination of the soul unveiled. No instrument—the human voice hai'dly excepted provides such a rare vehicle for the emotions—is in such close touch with the molecular vibrations of thought and with the psychic waves of feeling. -

B&F Magazine Issue 30

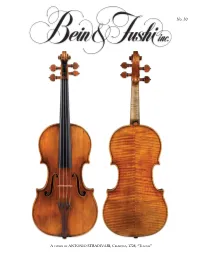

No. 30 A VIOLIN BY ANTONIO STRADIVARI, CREMONA, 1728, “THUNIS” FM’s “Impromptu” program, which combines live performance with interviews. Fellow recipient Philippe Quint, of the “Ruby” Stradivari violin of 1708, was a guest on the show in January. Their performances were spectacular. Paul played music by Zarzycki, Sibelius, Sarasate, and Saint-Saëns and Philippe presented works by Gershwin, Saint-Saëns and Tchaikovsky/ Auer. Both spoke at length about the Stradivari Dear Friends, Society and its mission to listeners throughout the With winter finally behind us, our thoughts turn to metropolitan area and around the world on the the outdoors once again and the great summer music internet. For more about Philippe, see page 13. institutes and concert series that are just around the Welcome, Valentina! corner. At Bein & Fushi, we maintain the highest standard of excellence in the inventory we offer. Since Congratulations to Stradivari Society patrons the demand for the most outstanding instruments is still Angelique and Daniel! It is with the greatest pleasure growing at a rapid pace around the world, making the that we introduce you to their supply increasingly limited, only at Bein & Fushi will first child, Valentina, born on you find such a superb selection and range of the finest October 31, 2014. Angelique antique and modern violins, violas, cellos, and bows. and Daniel generously loan the magnificent “Wahl” Master Teachers Take Center Stage Pietro Guarneri II violin of We are proud to feature two remarkable teachers 1735 to Society recipient and dear friends, Sonja Foster and Drew Lecher, Sandy Cameron. We think in this edition of our magazine. -

Inventing the Italian Violin Making “Tradition”: Franjo / Franz / Francesco Kresnik, a Physician and Violin Maker, As Its Key Figure in a Fascist Environment

Inventing the Italian Violin Making “Tradition”: Franjo / Franz / Francesco Kresnik, a Physician and Violin Maker, as Its Key Figure in a Fascist Environment Matej Santi All content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Received: 03/09/2019 Last updated: How to cite: Matej Santi, “Inventing the Italian Violin Making “Tradition”: Franjo / Franz / Francesco Kresnik, a Physician and Violin Maker, as Its Key Figure in a Fascist Environment,” Musicologica Austriaca: Journal for Austrian Music Studies ( ) Tags: 20th century; Bicentenario stradivariano; Fiume; Kresnik; Rijeka The cover image shows Kresnik in Cremona, 1937 (unidentifed photographer; by courtesy of the Maritime and History Museum of the Croatian Littoral). Abstract This article investigates the role played by the physician and violin maker Franz / Franjo / Francesco Kresnik in the discourse on violin making in the first half of the 20th century. It also considers the effect of his presence at the Bicentenario stradivariano, the 200th anniversary of the death of Antonio Stradivari in Cremona in 1937, during the Ventennio—the two decades of fascist rule. Art and music had at that time become central for the construction of national identity and the mobilization of the population by means of elaborate public events and media discourses. The Vienna-born Kresnik grew up in Fiume / Rijeka in present-day Croatia. After studying medicine in Vienna, Graz, and Innsbruck, he worked as a physician in Fiume / Rijeka and made violins in his spare time. He was always interested in the theory of violin making, and his visits to the collector Theodor Hämmerle in Vienna gave him the opportunity to examine several Cremonese violins from the 17th and 18th centuries. -

1. History of the Development of the Violin 2. Construction of the Violin 3

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-1975 1. History of the Development of the Violin 2. Construction of the Violin 3. Repairs of the Violin String Instruments Carl David Nyman Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the Music Education Commons Recommended Citation Nyman, Carl David, "1. History of the Development of the Violin 2. Construction of the Violin 3. Repairs of the Violin String Instruments" (1975). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 750. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/750 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HISTORY OF THE DEV E L OP~1EN T OF TH E VIOLIN II CON STRUCTION OF THE VIOLIN III REPAIRS OF TH E VIOLIN (STRING INSTRUMENTS) by Car l David Nyman Subm itted in partial fulfi ll ment of the requirements for the degree of ~1AS TER OF ~1USIC in ~1USIC EDUCATION Approved: UTAH STATE UN IVERS ITY LOGAN, UTAH ii ACK NOI,!LEDGME NTS I would like to exoress my ap preciation to Professor ~alph MaLesky for his encourageme nt, adv ice, and friendship . would also like to express my gratitude to the other members of my committee: Glen Fifield and Malcom Allred. I would be remiss if I did not specifical ly acknowledge Mr. -

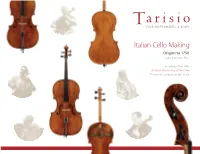

Italian Cello Making Origins to 1750 a Survey by Jason Price

Italian Cello Making Origins to 1750 A survey by Jason Price in collaboration with An Illustrated History of the Cello Exhibition curated by Jan Strick To celebrate the inaugural Queen Elisabeth Cello As a violin maker I often have the chance to Competition 2017, violin maker and expert Jan work on cellos made by the great luthiers of the Cremona Strick has curated an exhibition of fine instruments past. The further back in time we go, the more he earliest surviving identifiable cello was a few dozen known Nicolò illustrating the history of the cello since the 17th changes you see in the shape and size of each made by Andrea Amati (c. 1505–1577) in Amati cellos survive. For century. To accompany the exhibition, Jason Price ‘‘instrument, and the finest examples can give Cremona around 1550–70 as part of the col- whatever reason the main surveys the origins of Italian cello making and its us an idea of how its form has evolved. In this lection of decorated instruments made for supply of cellos in mid-to- th developments to 1750. exhibition we aim to show that evolution by TKing Charles IX of France. Given that there are only two late 17 -century Cremona other Andrea Amati cellos, which have survived in vary- appears to have come from bringing together examples which help trace ing states of alteration, there is much that is unknown two other workshops in the history of the cello. about the function and format of these cellos although Cremona: the Guarneri and we can accept that for Amati in the mid-16th century the Rugeri.