Stradivari Trust 25 Years of Instrument Trusts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stowell Make-Up

The Cambridge Companion to the CELLO Robin Stowell Professor of Music, Cardiff University The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 1RP,United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia © Cambridge University Press 1999 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1999 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Adobe Minion 10.75/14 pt, in QuarkXpress™ [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data ISBN 0 521 621011 hardback ISBN 0 521 629284 paperback Contents List of illustrations [page viii] Notes on the contributors [x] Preface [xiii] Acknowledgements [xv] List of abbreviations, fingering and notation [xvi] 21 The cello: origins and evolution John Dilworth [1] 22 The bow: its history and development John Dilworth [28] 23 Cello acoustics Bernard Richardson [37] 24 Masters of the Baroque and Classical eras Margaret Campbell [52] 25 Nineteenth-century virtuosi Margaret Campbell [61] 26 Masters of the twentieth century Margaret Campbell [73] 27 The concerto Robin Stowell and David Wyn Jones [92] 28 The sonata Robin Stowell [116] 29 Other solo repertory Robin Stowell [137] 10 Ensemble music: in the chamber and the orchestra Peter Allsop [160] 11 Technique, style and performing practice to c. -

Upbeat Summer 2017

UPBEATUPBEAT SUMMER 2017 NEWS FROM INSIDE THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF MUSIC IN THIS ISSUE AWARDING EXCELLENCE BREAKING NEW GROUND RISING STARS OF THE RCM HIGHLIGHTS FESTIVAL OF PERCUSSION 2017 The RCM’s annual Festival of Percussion returned on 7 May 2017 with an exceptional line-up of events and special guests. Visitors enjoyed performances from artists such as Benny Greb and the Band of the RAF Regiment, alongside family workshops, a day- long Trade Fair and toe-tapping evening concert with the RCM Big Band. Photos: Chris Christodoulou Front cover: Louise Alder at BBC Cardiff Singer of the World © Brian Tarr 2 UPBEAT SUMMER 2017 CONTENTS WELCOME 4 NEWS The latest news and activities from TO UPBEAT the Royal College of Music 9 As we went to press with the summer issue of Upbeat, news awarding EXCELLENCE of alumna Louise Alder’s success at the BBC Cardiff Singer of Upbeat explores the history behind the RCM’s most prestigious awards the World 2017 competition made its way to the Royal College of Music. Louise won the prestigious Dame Joan Sutherland Audience 10 Prize after getting through to the Song Prize and Main Prize finals of the WHERE ARE THEY NOW? Find out what some of our award competition, and I am thrilled that she has rightly earned a place on the front winners are up to in this special cover of Upbeat. Find out more on page seven. extended article, featuring interviews with Ieuan Jones, Charlotte Harding, On graduating from the RCM in 2013 Louise received the Tagore Gold Katy Woolley and Ruairi Glasheen Medal, an award that was first given out more than a century ago to outstanding students. -

What Makes Me Feel Drawn to KROKE Music Is Spiritual Reality of the Musicians, This Means Honesty and Authenticity of the Music

What makes me feel drawn to KROKE music is spiritual reality of the musicians, this means honesty and authenticity of the music. Nigel Kennedy The music is too dark to really represent traditional klezmer. At times, it is almost as if the Velvet Underground have been reborn as a klezmer band. Ari Davidov KROKE live are a hair-raisingly brilliant, unforgettable experience. John Lusk At times they sound jazzy, at times contemporary, at times classical. Their music is at once passionate and danceable. Dominic Raui KROKE (which means Kraków in Yiddish) was formed in 1992 by three friends and graduates of the Kraków Academy of Music: Jerzy Bawoł (accordion), Tomasz Kukurba (viola) and Tomasz Lato (double bass). The members of the group completed all stages of standard music education, including contemporary music. KROKE began by playing klezmer music, which is deeply set in Jewish tradition, and adding a strong influence of Balkan music. Currently, they draw inspiration from a variety of ethnic music from around the world, combining it with elements of jazz and improvisation, creating their own distinctive style. Initially, KROKE performed only in clubs and galleries situated in Kazimierz, a former Jewish district of Kraków. There, for the first time, one could listen to KROKE's songs. They later recorded their first cassette released at their own expense in 1993. While performing at the Ariel gallery, they came to the attention of Steven Spielberg, who was shooting Schindler's List in Kraków at the time. Spielberg invited them to Jerusalem, where he was shooting the final scenes. The group performed a concert at the Survivors' Reunion for those of Oskar Schindler's list who made it through the war. -

14 January 2011 Page 1 of 9

Radio 3 Listings for 8 – 14 January 2011 Page 1 of 9 SATURDAY 08 JANUARY 2011 05:37AM virtuosity, but it's quite possible he wrote this concerto to play Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus (1756-1791) himself. One early soloist commented that the middle SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b00wx4v1) Alma Dei creatoris (K.277) movement was 'too clever by half', but it's the finale that's The Genius of Mozart, presented by John Shea Ursula Reinhardt-Kiss (soprano); Annelies Burmeister (mezzo); catches most attention today, as it suddenly lurches into the Eberhard Büchner (tenor); Leipzig Radio Chorus & Symphony 'Turkish' (or more accurately Hungarian-inspired) style - and 01:01AM Orchestra), Herbert Kegel (conductor) the nickname has stuck. Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus (1756-1791) Thamos, König in Ägypten (K.345) 05:43AM Conductor Garry Walker is no stranger to Mozart, last season Monteverdi Choir; English Baroque Soloists; cond. by John Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus (1756-1791) he visited the St David's Festival in West Wales with the Eliot Gardiner 16 Minuets (K.176) (excerpts) Nos.1-4 orchestra, taking the 'Haffner' symphony. Today he conducts Slovak Sinfonietta, cond. Tara Krysa the players in Symphony No. 25, written when Mozart was a 01:50AM teenager. It's his first symphony in a minor key, and maybe the Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus (1756-1791) 05:51AM passion and turbulence we hear in the outer movements a young Piano Sonata in C minor (K. 457) (1784) Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus (1756-1791) man struggling out of his adolescence. Denis Burstein (piano) Quartet for strings in B flat major (K.458) "Hunt" Quatuor Mosaïques MOZART 02:15AM Violin Concerto No. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

MOZART Symphonies 29,31,32,35,36

ALSO AVAILABLE ON LINN RECORDS MOZART Requiem ................................................CKD 211 MOZART Wind Concertos .................................CKD 273 MOZART Serenades ..............................................CKD 287 MOZART Symphonies 38~41 ..........................CKD 308 MOZART Colloredo Serenade............................CKD 320 MOZART Symphonies 29,31,32,35,36 ..........CKD 350 MENDELSSOHN Symphony No.3 ‘Scottish’ ..............CKD 216 SIBELIUS Theatre Music......................................CKD 220 BRAHMS Violin Concerto ..................................CKD 224 BARTÓK Strings, Percussion & Celeste ........CKD 234 PROKOFIEV Symphony No.1 in D major............CKD 219 DVORˇÁK Violin Concerto ..................................CKD 241 BEETHOVEN Piano Concertos 3,4,5 ......................CKD 336 Available on SACD and Studio Master Download from www.linnrecords.com Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) Divertimento K.334 GIVEN THAT CHAMBER MUSIC takes such an important place in Mozart’s output Oboe Quartet K.370 – the great string quintets and quartets, and the wonderful range of works with SCOTTISH CHAMBER piano – it seems surprising that in the first years of his maturity, from 1774, say, ORCHESTRA ENSEMBLE until 1781, he wrote so little. His earlier string quartets, dating from between Alexander Janiczek director / violin*† 1770 and 1773, had been associated with visits to Italy and Vienna; in Salzburg, it seems, there was more call for serenade music for orchestra or wind ensemble, Divertimento No.17 in D Major Ruth Crouch violin* for 2 violins, viola, bass and 2 horns * Jane Atkins viola*† often performed out-of-doors. There is, however, an important series of works David Watkin cello† for strings and two horns (K.205, 247, 287 and 334) that are designed for single 1 March K.445 (320c) ................................. 2.27 Nikita Naumov double bass* players and attest to his increasing mastery in writing for small ensembles. -

2019 Round Top Music Festival

James Dick, Founder & Artistic Director 2019 Round Top Music Festival ROUND TOP FESTIVAL INSTITUTE Bravo! We salute those who have provided generous gifts of $10,000 or more during the past year. These gifts reflect donations received as of May 19, 2019. ROUND TOP FESTIVAL INSTITUTE 49th SEASON PArtNER THE BURDINE JOHNSON FOUNDATION HERITAGE CIrcLE H-E-B, L .P. FOUNDERS The Brown Foundation Inc. The Clayton Fund The Estate of Norma Mary Webb BENEFACTORS The Mr. and Mrs. Joe W. Bratcher, Jr. Foundation James C. Dick Mark and Lee Ann Elvig Robert J. Kleberg, Jr. and Helen C. Kleberg Foundation Richard R. Royall V Rose P. VanArsdel SUSTAINERS Blue Bell Creameries, L.P. William, Helen and Georgina Hudspeth Nancy Dewell Braus Luther King Capital Management The Faith P. and Charles L. Bybee Foundation Paula and Kenneth Moerbe Malinda Croan Anna and Gene Oeding Mandy Dealey and Michael Kentor The Gilbert and Thyra Plass Arts Foundation Dickson-Allen Foundation Myra Stafford Pryor Charitable Trust June R. Dossat Dr. and Mrs. Rolland C. Reynolds and Yvonne Reynolds Dede Duson Jim Roy and Rex Watson Marilyn T. Gaddis Ph.D. and George C. Carruthers Tod and Paul Schenck Ann and Gordon Getty Foundation Texas Commission on the Arts Alice Taylor Gray Foundation Larry A. Uhlig George F. Henry Betty and Lloyd Van Horn Felicia and Craig Hester Lola Wright Foundation Joan and David Hilgers Industry State Bank • Fayetteville Bank • First National Bank of Bellville • Bank of Brenham • First National Bank of Shiner ® Bravo! Welcome to the 49th Round Top Music Festival ROUND TOP FESTIVAL INSTITUTE The sole endeavor of The James Dick Foundation for the Performing Arts To everything There is a season And a time to every purpose, under heaven A time to be born, a time to die A time to plant, a time to reap A time to laugh, a time to weep This season at Festival Hill has been an especially sad one with the loss of three of our beloved friends and family. -

Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series

Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series Frank Morelli, Bassoon Behind every Juilliard artist is all of Juilliard —including you. With hundreds of dance, drama, and music performances, Juilliard is a wonderful place. When you join one of our membership programs, you become a part of this singular and celebrated community. by Claudio Papapietro Photo of cellist Khari Joyner Photo by Claudio Papapietro Become a member for as little as $250 Join with a gift starting at $1,250 and and receive exclusive benefits, including enjoy VIP privileges, including • Advance access to tickets through • All Association benefits Member Presales • Concierge ticket service by telephone • 50% discount on ticket purchases and email • Invitations to special • Invitations to behind-the-scenes events members-only gatherings • Access to master classes, performance previews, and rehearsal observations (212) 799-5000, ext. 303 [email protected] juilliard.edu The Juilliard School presents Faculty Recital: Frank Morelli, Bassoon Jesse Brault, Conductor Jonathan Feldman, Piano Jacob Wellman, Bassoon Wednesday, January 17, 2018, 7:30pm Paul Hall Part of the Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series GIOACHINO From The Barber of Seville (1816) ROSSINI (arr. François-René Gebauer/Frank Morelli) (1792–1868) All’idea di quell metallo Numero quindici a mano manca Largo al factotum Frank Morelli and Jacob Wellman, Bassoons JOHANNES Sonata for Cello, No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 38 (1862–65) BRAHMS Allegro non troppo (1833–97) Allegro quasi menuetto-Trio Allegro Frank Morelli, Bassoon Jonathan Feldman, Piano Intermission Program continues Major funding for establishing Paul Recital Hall and for continuing access to its series of public programs has been granted by The Bay Foundation and the Josephine Bay Paul and C. -

Saken Bergaliyev Matr.Nr. 61800203 Benjamin Britten Lachrymae

Saken Bergaliyev Matr.Nr. 61800203 Benjamin Britten Lachrymae: Reflections on a Song of Dowland for viola and piano- reflections or variations? Master thesis For obtaining the academic degree Master of Arts of course Solo Performance Viola in Anton Bruckner Privatuniversität Linz Supervised by: Univ.Doz, Dr. M.A. Hans Georg Nicklaus and Mag. Predrag Katanic Linz, April 2019 CONTENT Foreword………………………………………………………………………………..2 CHAPTER 1………………………………...………………………………….……....6 1.1 Benjamin Britten - life, creativity, and the role of the viola in his life……..…..…..6 1.2 Alderburgh Festival……………………………......................................................14 CHAPTER 2…………………………………………………………………………...19 John Dowland and his Lachrymae……………………………….…………………….19 CHAPTER 3. The Lachrymae of Benjamin Britten.……..……………………………25 3.1 Lachrymae and Nocturnal……………………………………………………….....25 3.2 Structure of Lachrymae…………………………………………………………....28 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………..39 Bibliography……………………………………….......................................................43 Affidavit………………………………………………………………………………..45 Appendix ……………………………………………………………………………....46 1 FOREWORD The oeuvre of the great English composer Benjamin Britten belongs to one of the most sig- nificant pages of the history of 20th-century music. In Europe, performers and the general public alike continue to exhibit a steady interest in the composer decades after his death. Even now, the heritage of the master has great repertoire potential given that the number of his written works is on par with composers such as S. Prokofiev, F. Poulenc, D. Shostako- vich, etc. The significance of this figure for researchers including D. Mitchell, C. Palmer, F. Rupprecht, A. Whittall, F. Reed, L. Walker, N. Abels and others, who continue to turn to various areas of his work, is not exhausted. Britten nature as a composer was determined by two main constants: poetry and music. In- deed, his art is inextricably linked with the word. -

Navigating, Coping & Cashing In

The RECORDING Navigating, Coping & Cashing In Maze November 2013 Introduction Trying to get a handle on where the recording business is headed is a little like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall. No matter what side of the business you may be on— producing, selling, distributing, even buying recordings— there is no longer a “standard operating procedure.” Hence the title of this Special Report, designed as a guide to the abundance of recording and distribution options that seem to be cropping up almost daily thanks to technology’s relentless march forward. And as each new delivery CONTENTS option takes hold—CD, download, streaming, app, flash drive, you name it—it exponentionally accelerates the next. 2 Introduction At the other end of the spectrum sits the artist, overwhelmed with choices: 4 The Distribution Maze: anybody can (and does) make a recording these days, but if an artist is not signed Bring a Compass: Part I with a record label, or doesn’t have the resources to make a vanity recording, is there still a way? As Phil Sommerich points out in his excellent overview of “The 8 The Distribution Maze: Distribution Maze,” Part I and Part II, yes, there is a way, or rather, ways. But which Bring a Compass: Part II one is the right one? Sommerich lets us in on a few of the major players, explains 11 Five Minutes, Five Questions how they each work, and the advantages and disadvantages of each. with Three Top Label Execs In “The Musical America Recording Surveys,” we confirmed that our readers are both consumers and makers of recordings. -

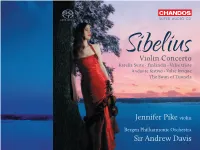

Jennifer Pike Violin Sir Andrew Davis

SUPER AUDIO CD SibeliusViolin Concerto Karelia Suite • Finlandia • Valse triste Andante festivo • Valse lyrique The Swan of Tuonela Jennifer Pike violin Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra Sir Andrew Davis AKG Images, London Images, AKG Jean Sibelius, at his house, Ainola, in Järvenpää, near Helsinki, 1907 Jean Sibelius (1865 – 1957) Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 47* 31:55 in D minor • in d-Moll • en ré mineur 1 I Allegro moderato – [Cadenza] – Tempo I – Molto moderato e tranquillo – Largamente – Allegro molto – Moderato assai – [Cadenza] – Allegro moderato – Allegro molto vivace 15:46 2 II Adagio di molto 8:16 3 III Allegro, ma non tanto 7:44 Karelia Suite, Op. 11 15:51 for Orchestra from music to historical tableaux on the history of Karelia 4 I Intermezzo. Moderato – Meno – Più moderato 4:03 5 II Ballade. Tempo di menuetto – Un poco più lento 7:13 Hege Sellevåg cor anglais 6 III Alla marcia. Moderato – Poco largamente 4:27 3 7 The Swan of Tuonela, Op. 22 No. 2 8:16 (Tuonelan joutsen) from the Lemminkäinen Legends after the Finnish national epic Kalevala compiled by Elias Lönnrot (1802 – 1884) Hege Sellevåg cor anglais Jonathan Aasgaard cello Andante molto sostenuto – Meno moderato – Tempo I 8 Valse lyrique, Op. 96a 4:09 Work originally for solo piano, ‘Syringa’ (Lilac), orchestrated by the composer Poco moderato – Stretto e poco a poco più – Tempo I 9 Valse triste, Op. 44 No. 1 5:03 from the incidental music to the drama Kuolema (Death) by Arvid Järnefelt (1861 – 1932) Lento – Poco risoluto – Più risoluto e mosso – Stretto – Lento assai 4 10 Andante festivo, JS 34b 4:06 Work originally for string quartet, arranged by the composer for strings and timpani ad libitum 11 Finlandia, Op. -

Sheku Kanneh-Mason

Sheku Kanneh-Mason Sheku Kanneh-Mason is the 2016 BBC Young Musician, a title he won with a stunning performance of the Shostakovich Cello Concerto at London’s Barbican Hall with the BBC Symphony Orchestra. In April 2017, Sheku returned to the hall for another performance of the concerto, this time with the National Youth Orchestra and Carlos Miguel Prieto after which the Guardian wrote that “technically superb and eloquent in his expressivity, he held the capacity audience spellbound with an interpretation of exceptional authority” and the Telegraph acknowledged “what a remarkable musician he already is, bringing other- worldly tone to the haunting slow movement and displaying mature musicianship in his handling of the extended cadenza” Only eighteen years old, Sheku’s international career is developing very quickly with engagements in the 2017/18 and 2018/19 seasons including the CBSO, the Philharmonia Orchestra at the Newbury Spring Festival, a return to the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra, Barcelona Symphony, Netherlands Chamber Orchestra (his debut at the Concertgebouw), Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra (Sheku’s concerto debut in North America), Louisiana Philharmonic, and the Seattle and Atlanta symphonies. He will also return to the BBC Symphony Orchestra to perform the Elgar Concerto in his hometown of Nottingham and make his debut at the Vienna Konzerthaus with the Japan Philharmonic. In recital, Sheku has several concerts across the UK with highlights over the next two seasons including his debuts at Kings Place as part of their Cello Unwrapped series, Milton Court, and Wigmore Hall. He will also perform a series of concerts in Canada in December 2017, and further recitals at the Zurich Tonhalle, and the Lucerne Festival.