Old Violins and VIOLIN LORE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ludwig Van Beethoven: the String Trios

Ludwig van Beethoven: The String Trios Sinae Baek, violin Cesia Corrales, viola Paul Christopher, cello Program Notes by Jackson Harmeyer Tonight’s program centers on the trios of Beethoven, and we hear two of these—numerically the first and the last in The genre of string trio was one which occupied Ludwig his catalogue. The String Trio in E-flat major, Opus 3, is van Beethoven for only a few years. All five of his trios for Beethoven’s earliest, published in 1796. Much like the trio violin, viola, and cello were written in the 1790s and by Mozart, which he had titled “Divertimento,” published in Vienna. Beethoven would write no further Beethoven’s Opus 3 is in six movements and follow his string trios after starting his impressive cycle of sixteen same pattern. Both trios begin with a fast first movement string quartets in 1798. Yet, alongside the one string trio which applies sonata principle; they continue with a slow produced by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, the five created second movement, a minuet, another slow movement, and by Beethoven are regarded as the greatest works of their another minuet; and finally conclude with a fast sixth genre produced in the eighteenth century. Together they movement in rondo form. Beethoven even snatches mark the first pinnacle in this genre’s history, as Mozart’s conspicuous key signature of E-flat major, one Beethoven’s turn away from the string trio would prove which would have posed difficulties for string players of symptomatic of a larger trend: though the eighteenth that era. -

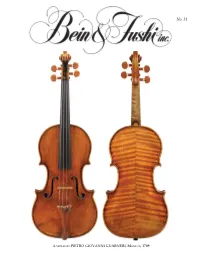

B&F Magazine Issue 31

No. 31 A VIOLIN BY PIETRO GIOVANNI GUARNERI, MANTUA, 1709 superb instruments loaned to them by the Arrisons, gave spectacular performances and received standing ovations. Our profound thanks go to Karen and Clement Arrison for their dedication to preserving our classical music traditions and helping rising stars launch their careers over many years. Our feature is on page 11. Violinist William Hagen Wins Third Prize at the Queen Elisabeth International Dear Friends, Competition With a very productive summer coming to a close, I am Bravo to Bein & Fushi customer delighted to be able to tell you about a few of our recent and dear friend William Hagen for notable sales. The exquisite “Posselt, Philipp” Giuseppe being awarded third prize at the Guarneri del Gesù of 1732 is one of very few instruments Queen Elisabeth Competition in named after women: American virtuoso Ruth Posselt (1911- Belgium. He is the highest ranking 2007) and amateur violinist Renee Philipp of Rotterdam, American winner since 1980. who acquired the violin in 1918. And exceptional violins by Hagen was the second prize winner Camillo Camilli and Santo Serafin along with a marvelous of the Fritz Kreisler International viola bow by Dominique Peccatte are now in the very gifted Music Competition in 2014. He has hands of discerning artists. I am so proud of our sales staff’s Photo: Richard Busath attended the Colburn School where amazing ability to help musicians find their ideal match in an he studied with Robert Lipsett and Juilliardilli d wherehh he was instrument or bow. a student of Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho. -

A Violin by Giuseppe Giovanni Battista Guarneri

141 A VIOLIN BY GIUSEPPE GIOVANNI BATTISTA GUARNERI Roger Hargrave, who has also researched and drawn the enclosed poster, discusses an outstanding example of the work of a member of the Guarneri family known as `Joseph Guarneri filius Andrea'. Andrea Guarneri was the first He may never have many details of instruments by of the Guarneri family of violin reached the heights of his Joseph filius at this period recall makers and an apprentice of contemporary, the Amati school, this type of Nicola Amati (he was actually varnish, in combination with registered as living in the house Antonio Stradivarius, but he the freer hand of Joseph, gives of Nicola Amati in 1641). Andrea's does rank as one of the the instruments a visual impact youngest son, whose work is il - greatest makers of all time. never achieved by an Amati or , lustrated here, was called. We should not forget he with the exception of Stradi - Giuseppe. Because several of the sired and trained the great vari, by any other classical Guarneri family bear the same del Gesu' maker before this time. christian names, individuals have traditionally been identified by a It should be said, however, suffix attached to their names. that the varnish of Joseph filius Thus, Giuseppe's brother is known as `Peter Guarneri varies considerably. It is not always of such out - of Mantua' to distinguish him from Giuseppe's son, standing quality the same can be said of Joseph's pro - who is known as `Peter Guarneri of Venice'. duction in general. If I were asked to describe the instruments of a few of the great Cremonese makers Giuseppe himself is called 'Giuseppe Guarneri filius in a single word, I would say that Amatis (all of them) Andrea' or, more simply, `Joseph filius' to distinguish are `refined', Stradivaris are `stately', del Gesus are him from his other son, the illustrious 'Giuseppe `rebellious' and the instruments of Joseph filius An - Guarneri del Gesu'. -

Biannual Report

Biannual Report Department of Mathematics 2007 and 2008 Contents 1 The Department of Mathematics 6 2 Research 8 2.1 Research Groups . 8 2.1.1 Algebra, Geometry and Functional Analysis . 8 2.1.2 Analysis . 16 2.1.3 Applied Geometry . 29 2.1.4 Didactics and Pedagogics of Mathematics . 32 2.1.5 Logic . 44 2.1.6 Numerics and Scientific Computing . 56 2.1.7 Optimization . 64 2.1.8 Stochastics . 85 2.2 Memberships in Scientific Boards and Committees . 92 2.3 Awards and Offers . 93 3 Teaching and Learning 95 3.1 Study Programs in Mathematics . 95 3.2 Service Teaching . 96 3.3 Characteristics in Teaching . 97 3.4 E-Learning/E-Teaching in Academic Training . 98 3.5 Student Body of the Department . 99 4 Publications 101 4.1 Co-Editors of Publications . 101 4.1.1 Editors of Journals . 101 4.1.2 Editors of Proceedings . 103 4.1.3 Editors of a Festschrift . 103 4.2 Monographs and Books . 103 4.3 Publications in Journals and Proceedings . 104 4.3.1 Journals . 104 4.3.2 Proceedings and Chapters in Collections . 118 4.4 Preprints . 125 4.5 Reviewing and Refereeing . 130 4.5.1 Reviewing Articles and Books . 130 4.5.2 Refereeing for Journals, Proceedings, and Publishers . 130 4.6 Software . 134 4.7 Postdoctoral lecture qualification (Habilitationen) . 135 4.8 Dissertations . 135 4.9 Master Theses and Theses for the State Board Examinations . 137 5 Presentations 146 5.1 Talks and Visits . 146 5.1.1 Invited Talks and Addresses . -

Download Press Release

Borletti-Buitoni Trust Press Release: 21 September 2020 CELEBRATING 20 YEARS Italian Postcards Avie AV2436 Release date 20 November 2020 Hugo Wolf (1860-1903) Italian Serenade in G Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) String Quartet No.1 in G, K.80, Lodi Nimrod Borenstein (1969 -) Cieli d’Italia, Op.88 for string quartet Pyotr Ilych Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) String Sextet in D minor, Op.70, Souvenir de Florence An album of chamber works inspired by the beauty of Italy, including a work specially commissioned for the recording, celebrates the 20th birthday of the renowned Italian ensemble Quartetto di Cremona. It is also, in part, a tribute to the late Italian philanthropist and music lover Franco Buitoni, co-founder with his wife, Ilaria, of the Borletti-Buitoni Trust. A special award was created in his name, which was designated in 2019 for Italian musicians who promote and encourage chamber music at home and throughout the world. The Franco Buitoni Award made this recording possible for the Quartet, which also won a BBT Fellowship award in 2005. With its Italian heritage to the fore, the Quartet chose works by composers who travelled to Italy and were inspired by its breathtaking scenery, rich culture and profound sense of history. The country’s splendours undoubtedly fed the creative spirit of Hugo Wolf, best known as one of the finest eXponents of the art song, including his celebrated Italienishes Liederbuch. The Italian Serenade is his most famous instrumental work, originally written for string quartet, but never performed publicly in Wolf’s lifetime and only published shortly after his death. -

Die Sammlung Historischer Streichinstrumente Der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank

OESTERREICHISCHE NATIONALBANK EUROSYSTEM Die Sammlung historischer Streichinstrumente der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank The collection of Historical String Instruments of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank Inhaltsverzeichnis Contents Impressum Medieninhaberin: Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Otto-Wagner-Platz 3, 1090 Wien, T: (+43 1) 404 20-6605, F: (+43 1) 404 20-6697, www.oenb.at Redaktion: Mag. Brigitte Alizadeh-Gruber, Muna Kadum, Martina Leitner, Mag. Irene Mühldorf Grafik, Layout und Satz: Melanie Schuhmacher Fotos: © Graphisches Atelier Neumann, Wien Druck: Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Abteilung für Öffentlichkeitsarbeit und Publikationen, Gruppe Multimedia-, Internet- und Print-Service. © Oesterreichische Nationalbank, 2013. Streichinstrumente/ String Instruments 9 Amati Andrea 10 Violoncello, Cremona, spätes 16. Jh. 10 Bergonzi Carlo 12 Violine, Cremona 1723 12 Violine, Cremona nach 1724 14 Bergonzi Michelangelo 16 Violine, Cremona um 1740 16 Violine, „ex Hamma-Segelman“, Cremona um 1750 18 Camilli Camillus 20 Violine, Mantua 1736 20 Ceruti Giovanni Battista 22 Viola, Cremona um 1810 22 Gagliano Alessandro 24 Violoncello, Neapel ca. 1710 24 Grancino Giovanni 26 Violoncello, „ex Piatti“ – „ex Dunlop“, Mailand 1706 26 Guadagnini Giovanni Battista 28 Violoncello, „ex von Zweygberg“, Piacenza 174. 28 Violine, Mailand 1749 30 Violine, „ex Meinel“, Turin um 1770–1775 32 Violine, Turin 1772 34 Violine, „Mantegazza“, Turin 1774 36 Violine, Turin 177. 38 Viola, Turin 1784 40 Guarneri Andrea 42 Violine, Cremona, Mitte 17. Jh. 42 Guarneri del Gesù Giuseppe 44 Violine, „ex Sorkin“, Cremona 1731 44 Violine, „ex Guilet“, Cremona nach 1732 46 Violine, „ex Carrodus“, Cremona 1741 48 Lorenzini Gaspare 50 Violine, Piacenza um 1760 50 Maggini Giovanni Paolo 52 Viola, Brescia, frühes 17. Jh. 52 Montagnana Domenico 54 Violine, Venedig 1727 54 Seraphin Sanctus 56 Violine, Venedig 1733 56 Violine, „ex Hamma“, Venedig nach 1748 58 Silvestre Pierre 60 Violine, „ex Moser“, Lyon ca. -

Reconstructing Lost Instruments Praetorius’S Syntagma Musicum and the Violin Family C

Prejeto / received: 3. 5. 2019. Odobreno / accepted: 12. 9. 2019. doi: 10.3986/dmd15.1-2.07 RECONSTRUCTING LOST INSTRUMENTS Praetorius’S Syntagma musicum and the Violin Family C. 1619 Matthew Zeller Duke University Izvleček: Knjigi De organographia in Theatrum Abstract: Michael Praetorius’s De organographia instrumentorum Michaela Praetoriusa vsebujeta and Theatrum instrumentorum provide valuable dragocene namige, ki pomagajo pri poznavanju clues that contribute to a new understanding glasbil iz družine violin okoli leta 1619; številna of the violin family c. 1619, many surviving ex- preživela glasbila so manjša, kot so bili izvirniki amples of which are reduced in size from their v 16. in 17. stoletju. Podatki o preživelih glas- sixteenth- and seventeenth-century dimensions. bilih – predvsem izdelki družine Amati – skupaj The record of surviving instruments – especially z metrologijo, sekundarno dokumentacijo in those of the Amati family – alongside metrologic, ikonografskim gradivom kažejo na to, da je documentary and iconographic evidence shows Michael Praetorius opisal veliko glasbilo, po that Michael Praetorius describes a large in- velikosti izjemno podobno violončelu (basso strument conforming remarkably well to the da braccio),kar je odličen primer predstavitve original dimensions of the basso da braccio glasbila iz družine violin in točne uglasitve, kot (violoncello), as well as furnishing an excellent so jih poznali v času izida Praetoriusovega dela. scale representation of the violin family as it was at the time of these works’ -

Late Fall 2020 Classics & Jazz

Classics & Jazz PAID Permit # 79 PRSRT STD PRSRT Late Fall 2020 U.S. Postage Aberdeen, SD Jazz New Naxos Bundle Deal Releases 3 for $30 see page 54 beginning on page 10 more @ more @ HBDirect.com HBDirect.com see page 22 OJC Bundle Deal P.O. Box 309 P.O. 05677 VT Center, Waterbury Address Service Requested 3 for $30 see page 48 Classical 50% Off beginning on page 24 more @ HBDirect.com 1/800/222-6872 www.hbdirect.com Classical New Releases beginning on page 28 more @ HBDirect.com Love Music. HBDirect Classics & Jazz We are pleased to present the HBDirect Late Fall 2020 Late Fall 2020 Classics & Jazz Catalog, with a broad range of offers we’re sure will be of great interest to our customers. Catalog Index Villa-Lobos: The Symphonies / Karabtchevsky; São Paulo SO [6 CDs] In jazz, we’re excited to present another major label as a Heitor Villa-Lobos has been described as ‘the single most significant 4 Classical - Boxed Sets 3 for $30 bundle deal – Original Jazz Classics – as well as a creative figure in 20th-century Brazilian art music.’ The eleven sale on Double Moon, recent Enlightenment boxed sets and 10 Classical - Naxos 3 for $30 Deal! symphonies - the enigmatic Symphony No. 5 has never been found new jazz releases. On the classical side, HBDirect is proud to 18 Classical - DVD & Blu-ray and may not ever have been written - range from the two earliest, be the industry leader when it comes to the comprehensive conceived in a broadly Central European tradition, to the final symphony 20 Classical - Recommendations presentation of new classical releases. -

Violin Detective

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS instruments have gone up in value after I found that their soundboards matched trees known to have been used by Stradivari; one subsequently sold at auction for more than four times its estimate. Many convincing for- KAMILA RATCLIFF geries were made in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but the science did not exist then. Forgers now are aware of dendro- chronology, and it could be a problem if they use wood from old chalets to build sophisti- cated copies of historical instruments. How about unintentional deceit? I never like to ‘kill’ a violin — reveal it as not what it seems. But if the wood does not match the claims, I investigate. I was recently sent photos of a violin supposedly made by an Italian craftsman who died in 1735. The wood dated to the 1760s, so I knew he could not have made it. But I did see strong cor- relations to instruments made by his sons and nephews who worked in the 1770s. So Peter Ratcliff restores and investigates violins from his workshop in Hove, UK. I deduced that the violin might have been damaged and an entirely new soundboard made after the craftsman’s death. The violin Q&A Peter Ratcliff was pulled from auction, but not before it had received bids of more than US$100,000. Will dendrochronology change the market? Violin detective I think it already has, and has called into Peter Ratcliff uses dendrochronology — tree-ring dating — to pin down the age and suggest the question some incorrect historical assump- provenance of stringed instruments. -

A Pedagogical Analysis of Dvorak's Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op

A Pedagogical Analysis of Dvorak’s Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 by Zhuojun Bian B.A., The Tianjin Normal University, 2006 M.Mus., University of Victoria, 2011 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Cello) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2017 © Zhuojun Bian, 2017 Abstract I first heard Antonin Dvorak’s Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 when I was 13 years old. It was a memorable experience for me, and I was struck by the melodies, the power, and the emotion in the work. As I became more familiar with the piece I came to understand that it holds a significant position in the cello repertory. It has been praised extensively by cellists, conductors, composers, and audiences, and is one of the most frequently performed cello concertos since it was premiered by the English cellist Leo Stern in London on March 19th, 1896, with Dvorak himself conducting the Philharmonic Society Orchestra. In this document I provide a pedagogical method as a practical guide for students and cello teachers who are planning on learning this concerto. Using a variety of historical sources, I provide a comprehensive understanding of some of the technical challenges presented by this work and I propose creative and effective methods for conquering these challenges. Most current studies of Dvorak’s concerto are devoted to the analysis of its structure, melody, harmony, rhythm, texture, instrumentation, and orchestration. Unlike those studies, this thesis investigates etudes and student concertos that were both precursors to – and contemporary with – Dvorak’s concerto. -

Symposium Records Cd 1109 Adolf Busch

SYMPOSIUM RECORDS CD 1109 The Great Violinists – Volume 4 ADOLF BUSCH (1891-1952) This compact disc documents the early instrumental records of the greatest German-born musician of this century. Adolf Busch was a legendary violinist as well as a composer, organiser of chamber orchestras, founder of festivals, talented amateur painter and moving spirit of three ensembles: the Busch Quartet, the Busch Trio and the Busch/Serkin Duo. He was also a great man, who almost alone among German gentile musicians stood out against Hitler. His concerts between the wars inspired a generation of music-lovers and musicians; and his influence continued after his death through the Marlboro Festival in Vermont, which he founded in 1950. His associate and son-in-law, Rudolf Serkin (1903-1991) maintained it until his own death, and it is still going strong. Busch's importance as a fiddler was all the greater, because he was the last glory of the short-lived German school; Georg Kulenkampff predeceased him and Hitler's decade smashed the edifice built up by men like Joseph Joachim and Carl Flesch. Adolf Busch's career was interrupted by two wars; and his decision to boycott his native country in 1933, when he could have stayed and prospered as others did, further fractured the continuity of his life. That one action made him an exile, cost him the precious cultural nourishment of his native land and deprived him of his most devoted audience. Five years later, he renounced all his concerts in Italy in protest at Mussolini's anti-semitic laws. -

Musical Instruments Monday 12 May 2014 Knightsbridge, London

Musical Instruments Monday 12 May 2014 Knightsbridge, London Musical Instruments Monday 12 May 2014 at 12pm Knightsbridge, London Bonhams Enquiries Customer Services Please see back of catalogue Montpelier Street Director of Department Monday to Friday for Notice to Bidders Knightsbridge Philip Scott 8.30am to 6pm London SW7 1HH +44 (0) 20 7393 3855 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 New bidders must also provide proof www.bonhams.com [email protected] of identity when submitting bids. Illustrations Failure to do this may result in your Viewing Specialist Front cover: Lot 273 & 274 bids not being processed. Friday 9 May Thomas Palmer Back cover: Lot 118 +44 (0) 20 7393 3849 9am to 4.30pm [email protected] IMPORTANT Saturday 10 May INFORMATION 11am to 5pm The United States Government Department Fax has banned the import of ivory Sunday 11 May +44 (0) 20 7393 3820 11am to 5pm Live online bidding is into the USA. Lots containing available for this sale ivory are indicated by the symbol Customer Services Ф printed beside the lot number Bids Please email [email protected] Monday to Friday 8.30am to 6pm with “Live bidding” in the in this catalogue. +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax subject line 48 hours before To bid via the internet the auction to register for Please register and obtain your this service. please visit www.bonhams.com customer number/ condition report for this auction at Please provide details of the lots [email protected] on which you wish to place bids at least 24 hours prior to the sale.