Symposium Records Cd 1109 Adolf Busch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biannual Report

Biannual Report Department of Mathematics 2007 and 2008 Contents 1 The Department of Mathematics 6 2 Research 8 2.1 Research Groups . 8 2.1.1 Algebra, Geometry and Functional Analysis . 8 2.1.2 Analysis . 16 2.1.3 Applied Geometry . 29 2.1.4 Didactics and Pedagogics of Mathematics . 32 2.1.5 Logic . 44 2.1.6 Numerics and Scientific Computing . 56 2.1.7 Optimization . 64 2.1.8 Stochastics . 85 2.2 Memberships in Scientific Boards and Committees . 92 2.3 Awards and Offers . 93 3 Teaching and Learning 95 3.1 Study Programs in Mathematics . 95 3.2 Service Teaching . 96 3.3 Characteristics in Teaching . 97 3.4 E-Learning/E-Teaching in Academic Training . 98 3.5 Student Body of the Department . 99 4 Publications 101 4.1 Co-Editors of Publications . 101 4.1.1 Editors of Journals . 101 4.1.2 Editors of Proceedings . 103 4.1.3 Editors of a Festschrift . 103 4.2 Monographs and Books . 103 4.3 Publications in Journals and Proceedings . 104 4.3.1 Journals . 104 4.3.2 Proceedings and Chapters in Collections . 118 4.4 Preprints . 125 4.5 Reviewing and Refereeing . 130 4.5.1 Reviewing Articles and Books . 130 4.5.2 Refereeing for Journals, Proceedings, and Publishers . 130 4.6 Software . 134 4.7 Postdoctoral lecture qualification (Habilitationen) . 135 4.8 Dissertations . 135 4.9 Master Theses and Theses for the State Board Examinations . 137 5 Presentations 146 5.1 Talks and Visits . 146 5.1.1 Invited Talks and Addresses . -

Everything Essential

Everythi ng Essen tial HOW A SMALL CONSERVATORY BECAME AN INCUBATOR FOR GREAT AMERICAN QUARTET PLAYERS BY MATTHEW BARKER 10 OVer tONeS Fall 2014 “There’s something about the quartet form. albert einstein once Felix Galimir “had the best said, ‘everything should be as simple as possible, but not simpler.’ that’s the essence of the string quartet,” says arnold Steinhardt, longtime first violinist of the Guarneri Quartet. ears I’ve been around and “It has everything that is essential for great music.” the best way to get students From Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert through the romantics, the Second Viennese School, Debussy, ravel, Bartók, the avant-garde, and up to the present, the leading so immersed in the act of composers of each generation reserved their most intimate expression and genius for that basic ensemble of two violins, a viola, and a cello. music making,” says Steven Over the past century america’s great music schools have placed an increasing emphasis tenenbom. “He was old on the highly specialized and rigorous discipline of quartet playing. among them, Curtis holds a special place despite its small size. In the last several decades alone, among the world and new world.” majority of important touring quartets in america at least one chair—and in some cases four—has been filled by a Curtis-trained musician. (Mr. Steinhardt, also a longtime member of the Curtis faculty, is one.) looking back, the current golden age of string quartets can be traced to a mission statement issued almost 90 years ago by early Curtis director Josef Hofmann: “to hand down through contemporary masters the great traditions of the past; to teach students to build on this heritage for the future.” Mary louise Curtis Bok created a haven for both teachers and students to immerse themselves in music at the highest levels without financial burden. -

Juilliard String Quartet

JUILLIARD STRING QUARTET ARETA ZHULLA - VIOLIN RONALD COPES - VIOLIN ROGER TAPPING - VIOLA ASTRID SCHWEEN - VIOLONCELLO „Decisive and uncompromising...Juilliard’s confidently thoughtful approach, rhythmic acuity and ensemble precision were on full display." – The Washington Post With unparalleled artistry and enduring vigor, the Juilliard String Quartet continues to inspire audiences around the world. Founded in 1946 and hailed by the Boston Globe as “the most important American quartet in history,” the Juilliard draws on a deep and vital engagement to the classics, while embracing the mission of championing new works, a vibrant combination of the familiar and the daring. Each performance of the Juilliard Quartet is a unique experience, bringing together the four members’ profound understanding, total commitment, and unceasing curiosity in sharing the wonders of the string quartet literature. Ms. Areta Zhulla joins the Juilliard Quartet as first violinist beginning this 2018-19 season which includes concerts in Hong Kong, Singapore, Shanghai, London, Oslo, Athens, Vancouver, Toronto and New York, with many return engagements all over the USA. The season will also introduce a newly commissioned String Quartet by the wonderful young composer, Lembit Beecher, and some piano quintet collaborations with the celebrated Marc-André Hamelin. In performance, recordings and incomparable work educating the major artists and quartets of our time, the Juilliard String Quartet has carried the banner of the United States and the Juilliard School throughout the world. Having recently celebrated its 70th anniversary, the Juilliard String Quartet marked the 2017-18 season with return appearances in Seattle, Santa Barbara, Pasadena, Memphis, Raleigh, Houston, Amsterdam, and Copenhagen. It continued its acclaimed annual performances in Detroit and Philadelphia, along with numerous concerts at home in New York City, including appearances at Lincoln Center and Town Hall. -

TOC 0245 CD Booklet.Indd

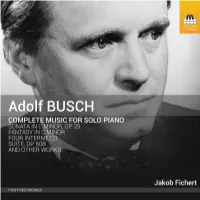

ADOLF BUSCH AND THE PIANO by Jakob Fichert It’s hardly a secret that Adolf Busch (1891–1952) was one of the greatest violinists of the twentieth century. But only specialists, it seems, are aware that he was also a very fne composer, even though these two artistic identities – performer and composer – were of equal importance to him. In recent years some of his chamber works, his organ music and parts of his symphonic œuvre have been recorded, allowing some appreciation of his stature as a creative fgure. But Busch’s music for solo piano has yet to be discovered – only the Andante espressivo, BoO1 37 22 , has been recorded before now, by Peter Serkin, Busch’s grandson, and that in a private recording, not available commercially. Tis album therefore presents the entirety of Busch’s piano output for the frst time. Busch’s writing for solo piano forms a kind of huge triptych, with the Sonata in C minor, Op. 25, as its central panel; another major work, a Fantasia in C major, BoO 20, was written early in his career; and a later Suite, Op. 60b, dates from the time of his full maturity. Busch also wrote more than a dozen smaller piano pieces, in which he seems to have experimented with various genres in pursuit of the development of his musical language, with four Intermezzi, a Scherzo and other character pieces among them. One can hear the infuence of Brahms, Mendelssohn, Busoni and – especially – Reger, but with familiarity Busch’s style can be heard to be distinctive and personal, displaying a unique and highly expressive world of sound. -

Marshall University Music Department Presents

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar All Performances Performance Collection Fall 11-7-2008 Marshall University Music Department Presents, Music Alive Series, Graffe trS ing Quartet, Štĕpán Graffe, violin, Lukáš Bednařik, violin, Lukáš Cybulski, viola, Michal Hreno, violoncello, with, Michiko Otaki, piano Michiko Otaki Štĕpán Graffe Lukáš Bednařik Lukáš Cybulski Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/music_perf Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Otaki, Michiko; Graffe, Štĕpán; Bednařik, Lukáš; and Cybulski, Lukáš, "Marshall University Music Department Presents, Music Alive Series, Graffe trS ing Quartet, Štĕpán Graffe, violin, Lukáš Bednařik, violin, Lukáš Cybulski, viola, Michal Hreno, violoncello, with, Michiko Otaki, piano" (2008). All Performances. 752. http://mds.marshall.edu/music_perf/752 This Recital is brought to you for free and open access by the Performance Collection at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Performances by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. DEPARTMENT of MUSIC Program String Quartet in g min.or, Franz Joseph Haydn op. 74, no. 3 ("Rider") (1732-1809) Allegro moderate MUSIC Largo assai Menuetto: Allegretto Finale: Allegro con brio presents the Quintet for Piano and Strings Robert Schumann Music Alive Series in E-flat major, op. 44 (1810-1856) Allegro brillante In modo d'una marcia GRAFFE STRING QUARTET Scherzo: Molto vivace Stepan Graffe, violin Allegro ma non troppo Lukas Bednarik, violin Lukas Cybulski, viola Michiko Otaki, piano Michal Hreno, violoncello with Michiko Otaki, piano Friday, November 7, 2008 Exclusive Management for the First Presbyterian Church GRAFFE QUARTET and MICHIKO OTAKI: 12:00 p.m. -

Juilliard String Quartet Areta Zhulla and Ronald Copes, Violins Roger Tapping, Viola Astrid Schween, Cello

Thursday Evening, December 12, 2019, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard String Quartet Areta Zhulla and Ronald Copes, Violins Roger Tapping, Viola Astrid Schween, Cello LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770–1827) String Quartet No. 1 in F major, Op. 18, No. 1 Allegro con brio Adagio affettuoso ed appassionato Scherzo: Allegro molto Allegro GYÖRGY KURTÁG (b. 1926) 6 Moments musicaux, Op. 44 Invocatio (Un fragment) Footfalls (… as if someone were coming) Capriccio In memoriam Sebok˝ György Rappel des oiseaux ... (Étude pour les harmoniques) Les adieux (in Janáceks˘ Manier) Intermission BEETHOVEN Quartet No. 14 in C-sharp minor, Op. 131 Adagio ma non troppo e molto espressivo Allegro molto vivace Allegro moderato—Adagio Andante, ma non troppo e molto cantabile Presto Adagio quasi un poco andante Allegro Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes, including an intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Notes on the Program published, in 1801. The D-major quartet (Op. 18, No. 3) was the first to be written; the By James M. Keller F-major (No. 1) and G-major (No. 2) followed, probably in that order; and the A major String Quartet No. 1 in F major, Op. 18, (No. 5), C minor (No. -

String Quartet 2 Notes.Odt

i Notes on the Scordatura Tuning This string quartet is written in an 11-limit just intonation system based on a Bb fundamental. To facilitate this a scordatura system has been designed wherein the strings of each instrument are tuned to harmonics of the Bb overtone series. The base ratios for each pitch are listed in the table below with their corresponding cent values relative to the fundamental. They are ordered by their distance from the fundamental. Pitch Bb Db D E1/4b F Ab Ratio and 1/1 = 0 c 7/6 = 266.8 c 5/4 = 386.3 c 11/8 = 551.3 c 3/2 = 702 c 7/4 = 968.8 c Cents (c) To further facilitate the scordatura tuning the following chart shows the desired frequency values in Hertz (Hz) for each string on each instrument. Instrument String IV String III String II String I Cello Bb 1 = 58.27 Hz F 2 = 87.405 Hz D 3 = 145.675 Hz Ab 3 = 203.945 Hz Viola Bb 2 = 116.54 Hz F 3 = 174.81 Hz Db 4 = 271.927 Hz Ab 4 = 407.89 Hz Violin II F 3 = 174.81 Hz Db 4 = 271.927 Hz Ab 4 = 407.89 Hz E1/4b = 640.97 Hz Violin I F 3 = 174.81 Hz D 4 = 291.35 Hz Ab 4 = 407.89 Hz E1/4b = 640.97 Hz The Cellist should tune their C string down to the desired Bb fundamental. Then they should tune the other strings to the 3rd (F), 5th (D), 7th (Ab) and 11th (E1/4b) harmonics of the "Bb string." Once all of the players have tuned their strings which correspond to harmonics of the Bb overtone series the second Violin and the Viola may tune the D string down to the 7/6 Db minor third by tuning it as a perfect 5th below the Ab string (7/4). -

View PDF Online

MARLBORO MUSIC 60th AnniversAry reflections on MA rlboro Music 85316_Watkins.indd 1 6/24/11 12:45 PM 60th ANNIVERSARY 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC Richard Goode & Mitsuko Uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 2 6/23/11 10:24 AM 60th AnniversA ry 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC richard Goode & Mitsuko uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 3 6/23/11 9:48 AM On a VermOnt HilltOp, a Dream is BOrn Audience outside Dining Hall, 1950s. It was his dream to create a summer musical community where artists—the established and the aspiring— could come together, away from the pressures of their normal professional lives, to exchange ideas, explore iolinist Adolf Busch, who had a thriving music together, and share meals and life experiences as career in Europe as a soloist and chamber music a large musical family. Busch died the following year, Vartist, was one of the few non-Jewish musicians but Serkin, who served as Artistic Director and guiding who spoke out against Hitler. He had left his native spirit until his death in 1991, realized that dream and Germany for Switzerland in 1927, and later, with the created the standards, structure, and environment that outbreak of World War II, moved to the United States. remain his legacy. He eventually settled in Vermont where, together with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, his brother Herman Marlboro continues to thrive under the leadership Busch, and the great French flutist Marcel Moyse— of Mitsuko Uchida and Richard Goode, Co-Artistic and Moyse’s son Louis, and daughter-in-law Blanche— Directors for the last 12 years, remaining true to Busch founded the Marlboro Music School & Festival its core ideals while incorporating their fresh ideas in 1951. -

A History of Rhythm, Metronomes, and the Mechanization of Musicality

THE METRONOMIC PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: A HISTORY OF RHYTHM, METRONOMES, AND THE MECHANIZATION OF MUSICALITY by ALEXANDER EVAN BONUS A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2010 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of _____________________________________________________Alexander Evan Bonus candidate for the ______________________Doctor of Philosophy degree *. Dr. Mary Davis (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) Dr. Daniel Goldmark ________________________________________________ Dr. Peter Bennett ________________________________________________ Dr. Martha Woodmansee ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________2/25/2010 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Copyright © 2010 by Alexander Evan Bonus All rights reserved CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES . ii LIST OF TABLES . v Preface . vi ABSTRACT . xviii Chapter I. THE HUMANITY OF MUSICAL TIME, THE INSUFFICIENCIES OF RHYTHMICAL NOTATION, AND THE FAILURE OF CLOCKWORK METRONOMES, CIRCA 1600-1900 . 1 II. MAELZEL’S MACHINES: A RECEPTION HISTORY OF MAELZEL, HIS MECHANICAL CULTURE, AND THE METRONOME . .112 III. THE SCIENTIFIC METRONOME . 180 IV. METRONOMIC RHYTHM, THE CHRONOGRAPHIC -

Adolf Busch: the Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set) Online

yiMmZ (Ebook pdf) Adolf Busch: The Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set) Online [yiMmZ.ebook] Adolf Busch: The Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set) Pdf Free Tully Potter DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #3756817 in Books Toccata Press 2010-09-17Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 3.97 x 7.32 x 9.02l, 7.55 #File Name: 09076895071408 pagesthe life and times of Adolf Busch, the "honest musician" | File size: 43.Mb Tully Potter : Adolf Busch: The Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Adolf Busch: The Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set): 9 of 10 people found the following review helpful. An Exemplary Life and Musical History of the TimesBy Edgar SelfLong awaited, this biography of violinist, composer, quartet and trio leader, teacher, and conductor Adolf Busch (1891-1952), co-founder of the Marlboro School of Music, is a history of the violin, of concerts and chamber-music in the first half of the 20th century. The texts, research notes, copious illustrations, and appendices detail virtually every concert and associate of Busch's life with full descriptions of his musical and personal relations with Reger, Busoni, Tovey, Roentgens and hundreds of others, including those unsympathetic to him such as Furtwaengler, Sibelius, Edwin Fischer, and Elly Ney, for musical or political reasons. Busch's early immigration from Germany and his part in creating the Lucerne Festival and Palestine Symphony Orchestra, precursor of the Israel Philharmonic, before settling in the U.S. -

The Busch Quartet Beethoven Volume 4 Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Busch Quartet Beethoven Volume 4 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Beethoven Volume 4 Country: UK Released: 2009 Style: Classical MP3 version RAR size: 1345 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1648 mb WMA version RAR size: 1589 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 721 Other Formats: TTA XM DMF AHX AU AUD APE Tracklist Quartet No.13 In B Flat Op.130 1 I: Adagio Ma non Troppo 8:56 2 II: Presto 1:54 3 III: Andante Con Moto, Ma Non Troppo 5:23 4 IV: Alla Danza Tedesca: Allegro Assai 2:23 5 V. Cavatina: Adagio Molto Espressivo 7:00 6 VI. Finale: Allegro 8:27 Quartet No.15 In A Minor Op.132 7 I: Assai Sostenuto - Allegro 4:03 8 II: Allegro Ma Non Tanto 6:15 III: Heilger Dankesang Eines Genesenen An Die Gottheit, In Der 9 3:45 Lydischen Tonart: Molto Adagio - Andante - Mit Innigster EmpFundung 10 IV: Alla Marcia, Assai Vivace 4:26 11 V. Allegro Appassionato Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Dutton Recorded At – Abbey Road Studios Credits Cello – Herman Busch* Composed By – Ludwig van Beethoven Ensemble – The Busch Quartet Liner Notes – Tully Potter Remastered By – Michael Dutton* Viola – Karl Doktor Violin – Adolph Busch, Gösta Andreasson (tracks: Gösta Andreassen) Notes Tracks 1 to 6: Recorded at Liederkranz Hall, NY 13 & 16 June 1941 Tracks 7 to 11: Recorded at Abbey Road Studio no. 3, on 7 October 1937 Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 7 65387 97942 3 Rights Society: MCPS SPARS Code: ADD Matrix / Runout: [Manufactured by kdg] 672.658 CDBP 9794 Mould SID Code: IFPI 3066 Related Music albums to Beethoven Volume 4 by The Busch Quartet Mendelssohn – Pacifica Quartet - The Complete String Quartets Beethoven - Alban Berg Quartett - Complete String Quartets Artur Schnabel, Ludwig van Beethoven - Beethoven the Complete Piano Sonatas on Thirteen Discs Beethoven, Paul Lewis - Complete Piano Sonatas John Lill - Beethoven Piano Sonatas Complete Vol I Beethoven, Juilliard String Quartet - Quartet In A Minor Op. -

Digital Booklet Porgy & Bess

71 TRACKS THE AMADEUS QUARtet ReCORDINGS VOL. I BEETHOVEN Berlin, 1950-1967 recording producer: Wolfgang Gottschalk (Op. 127) Hartung (Op. 59, 2) Hermann Reuschel (Op. 18, 2-5 / Op. 59, 1 / Op. 130-133 / Op. 135 / Op. 29) Salomon (Op. 18, 1+6 / Op. 59, 3 / Op. 95) recording engineer: Siegbert Bienert (Op. 18, 5 / Op. 130-133 / Op. 29) Peter Burkowitz (Op. 18, 6) THE Heinz Opitz (Op. 18, 2 / Op. 59, 1+2 / Op. 127 / Op. 135) Preuss (Op. 18, 1 / Op. 59, 3 / Op. 95) Alfred Steinke (Op. 18, 3+4) AMADEUS QUARtet ReCORDinGS Berlin, 1950-1967 Eine Aufnahme von RIAS Berlin (lizenziert durch Deutschlandradio) recording: P 1950 - 1967 Deutschlandradio research: Rüdiger Albrecht remastering: P 2013 Ludger Böckenhoff rights: audite claims all rights arising from copyright law and competition law in relation to research, compilation and re-mastering of the original audio tapes, VOL. I BEETHOVEN as well as the publication of this CD. Violations will be prosecuted. The historical publications at audite are based, without exception, on the original tapes from broadcasting archives. In general these are the original analogue tapes, MstASTER RELEASE which attain an astonishingly high quality, even measured by today’s standards, with their tape speed of up to 76 cm/sec. The remastering – professionally com- petent and sensitively applied – also uncovers previously hidden details of the interpretations. Thus, a sound of superior quality results. CD publications based 1 on private recordings from broadcasts cannot be compared with these. AMADEUS-QUARtett further reading: Daniel Snowman: The Amadeus Quartet. The Men and the Music, violin I Norbert Brainin Robson Books (London, 1981) violin II Siegmund Nissel Gerd Indorf: Beethovens Streichquartette, Rombach Verlag (Freiburg i.