Annual Report 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IATF Fact Sheet: Religion

1 FACT SHEET iataskforce.org Topic: Religion – Druze Updated: June 2014 The Druze community in Israel consists of Arabic speakers from an 11th Century off-shoot of Ismaili Shiite theology. The religion is considered heretical by orthodox Islam.2 Members of the Druze community predominantly reside in mountainous areas in Israel, Lebanon, and Syria.3 At the end of 2011, the Druze population in Israel numbered 133,000 inhabitants and constituted 8.0% of the Arab and Druze population, or 1.7%of the total population in Israel.4 The Druze population resides in 19 localities located in the Northern District (81% of the Druze population, excluding the Golan Heights) and Haifa District (19%). There are seven localities which are exclusively Druze: Yanuh-Jat, Sajur, Beit Jann, Majdal Shams, Buq’ata, Mas'ade, and Julis.5 In eight other localities, Druze constitute an overwhelming majority of more than 75% of the population: Yarka, Ein al-Assad, Ein Qiniyye, Daliyat al-Karmel, Hurfeish, Kisra-Samia, Peki’in and Isfiya. In the village of Maghar, Druze constitute an almost 60% majority. Finally, in three localities, Druze account for less than a third of the population: Rama, Abu Snan and Shfar'am.6 The Druze in Israel were officially recognized in 1957 by the government as a distinct ethnic group and an autonomous religious community, independent of Muslim religious courts. They have their own religious courts, with jurisdiction in matters of personal status and spiritual leadership, headed by Sheikh Muwaffak Tarif. 1 Compiled by Prof. Elie Rekhess, Associate Director, Crown Center for Jewish and Israel Studies, Northwestern University 2 Naim Araidi, The Druze in Israel, Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, December 22, 2002, http://www.mfa.gov.il; Gabriel Ben Dor, “The Druze Minority in Israel in the mid-1990s”, Jerusalem Letters, 315, June 1, 1995, JerusalemCenter for Public Affairs. -

High Schools

15 • Annual Report 2001 High Schools Harishonim, Herzlia Hayovel, Herzliya 16 • Annual Report 2001 17 • Annual Report 2001 Harishonim Harishonim High School, Herzliya Peace Network — Youth, the Internet, and Coexistence Ora Shnabel Young people, the future leaders and world citizens, can make a difference. In this project , they use the Internet to break down barriers between different cultures, and pave the way to coexistence. Peace Network is an educational project, which combines the use of the Internet with conflict resolution strategies. Students School. Last year two Junior High The vision is to spread the net begin their relationship by Schools, a Jewish and a Druze, and build a chain of schools for exchanging letters of introduction; from Herzliya and Abu-Snan peace and democracy in the they proceed with intercultural started to cooperate. They are Middle East. By getting acquainted surveys on topics like manners and continuing the project this year. with other cultures, barriers and politeness, the generation gap, The Druze school won a special prejudices will disappear, and by body-language and non-verbal prize from the Israeli Teachers’ learning conflict resolution communication. They meet face to Organization for participating in the strategies students will be able to face, study the same literary pieces project. By doing so they promote resolve conflicts in a creative way. with a message of tolerance, cooperation and coexistence. discuss topical matters, learn The website, which will appear in conflict resolution strategies and at Students active in the project also English, Hebrew and Arabic, will the end of the process, hold an participate once a year in The reflect the work done in the field, Internet relay chat on a real International Middle Eastern and will be so sophisticated and conflict, trying to come up with United Nations Conference, creative that politicians will visit creative solutions. -

Palestinian Internally Displaced Persons Inside Israel: Challenging the Solid Structures

Palestinian Internally Displaced Persons inside Israel: Challenging the Solid Structures Nihad Bokae’e February 2003 Badil Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights PO Box 728 Bethlehem, Palestine [email protected] www.badil.org Socio-historical Overview Internally displaced Palestinians inside Israel are part of the larger Palestinian refugee population that was displaced/expelled from their villages and homes during the 1948 conflict and war in Palestine (i.e., al-Nakba). Most of the refugees were displaced to the Arab states and the Palestinian territories that did not fall under Israeli control (i.e., the West Bank and Gaza Strip). At the end of the war, some 150,000 Palestinians remained in the areas of Palestine that became the state of Israel. This included approximately 30- 40,000 Palestinians who were also displaced during the war. Like the approximately 800,000 Palestinian refugees who were displaced/expelled beyond the borders of the new state, Israel refused to allow internally displaced Palestinians (IDPs) to return to their homes and villages. Displacement did not end with the 1948 war. In the years following the establishment of Israel, internally displaced Palestinians, a small number of refugees who had returned spontaneously to their villages, and Palestinians who had not been displaced during the war were expelled for security and other reasons. Israeli officials also carried out forced transfer of Palestinians from one village to another within the borders of the state in order to facilitate colonization of these areas. This included, for example, Palestinians from the villages of Iqrit, Bir’am, al-Ghabsiyya, Krad al-Baqqarah and Krad al- Ghannamah. -

NES AMMIM Der Völker Für Die Völker Inhalt

2020 | 2021 Ein Zeichen NES AMMIM der Völker für die Völker Inhalt Liebe Leserin und lieber Leser 1 Thomas Kremers Zeit für T´shuva: Die Bedeutung des jüdischen Neujahrs „Rosh HaShana“ 2 Rabbiner Or Zohar Jüdische Fest- und Fastentage 4 Impressum: Nes Ammim Deutschland e.V. Gedanken zur Umkehr 5 Hans-Böckler-Str. 7 Prof. Dr. Klaus Müller 40476 Düsseldorf Tel. (0049) (0)211/4562 493 Fax (0049) (0)211/4562 497 … aber Christus gehört nicht uns. 7 Dr. Rainer Stuhlmann E-Mail der Redaktion: [email protected] E-Mail des Büros: Wie Nes Ammim, Israel und die Palästinenser mit dem [email protected] Ausbruch von COVID-19 umgegangen sind Dr. Tobias Kriener 10 Spendenkonten: KD-Bank IBAN: DE17 3506 0190 1010 9880 19 Wie Corona unser Auslandsjahr beendete 14 BIC: GENODED1DKD Postbank Deborah Sausmikat, Silvia Pleines IBAN: DE40 3601 0043 0160 4884 38 BIC: PBNKDEFF Bewahren und erneuern – Nes Ammim auf dem Weg zu einer Peter Beier Stiftung Nes Ammim gemeinsam gestalteten Gemeinschaft 16 KD-Bank IBAN DE66 3506 0190 1013 4550 11 Thomas Kremers BIC GENODED1DKD Herausgeber Rezension zum Buch „Denk ich an Israel …“ 19 Nes Ammim Deutschland e.V. Thomas Kremers Thomas Kremers Redaktion Women Wage Peace – Peace-Carpet-Workshop 20 Liselotte Ueter, Natascha Kozlowski- Ueter, Sarah Ultes Tanja Maurer Technische Koordination Natascha Kozlowski-Ueter Arabische und jüdische Jugendliche diskutieren miteinander 21 Fotos Ofer Lior und Taiseer Khatib Copyright Nes Ammim, bzw. s. Angaben Arabische Kinder lernen Hebräisch 23 Gestaltung Michael Wichelhaus Ofer Lior und Taiseer Khatib Für den jeweiligen Inhalt der einzel- Seminar für Moderatorinnen und Moderatoren 24 nen Artikel sind die Verfasser und Taiseer Khatib und Ofer Lior Verfasserinnen verantwortlich. -

The Palestinians in Israel Readings in History, Politics and Society

The Palestinians in Israel Readings in History, Politics and Society Edited by Nadim N. Rouhana and Areej Sabbagh-Khoury 2011 Mada al-Carmel Arab Center for Applied Social Research The Palestinians in Israel: Readings in History, Politics and Society Edited by: Nadim N. Rouhana and Areej Sabbagh-Khoury اﻟﻔﻠﺴﻄﻴﻨﻴﻮن ﰲ إﴎاﺋﻴﻞ: ﻗﺮاءات ﰲ اﻟﺘﺎرﻳﺦ، واﻟﺴﻴﺎﺳﺔ، واملﺠﺘﻤﻊ ﺗﺤﺮﻳﺮ: ﻧﺪﻳﻢ روﺣﺎﻧﺎ وأرﻳﺞ ﺻﺒﺎغ-ﺧﻮري Editorial Board: Muhammad Amara, Mohammad Haj-Yahia, Mustafa Kabha, Rassem Khamaisi, Adel Manna, Khalil-Nakhleh, Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Mahmoud Yazbak Design and Production: Wael Wakeem ISBN 965-7308-18-6 © All Rights Reserved July 2011 by Mada Mada al-Carmel–Arab Center for Applied Social Research 51 Allenby St., P.O. Box 9132 Haifa 31090, Israel Tel. +972 4 8552035, Fax. +972 4 8525973 www.mada-research.org [email protected] 2 The Palestinians in Israel: Readings in History, Politics and Society Table of Contents Introduction Research on the Palestinians in Israel: Between the Academic and the Political 5 Areej Sabbagh-Khoury and Nadim N. Rouhana The Nakba 16 Honaida Ghanim The Internally Displaced Palestinians in Israel 26 Areej Sabbagh-Khoury The Military Government 47 Yair Bäuml The Conscription of the Druze into the Israeli Army 58 Kais M. Firro Emergency Regulations 67 Yousef Tayseer Jabareen The Massacre of Kufr Qassem 74 Adel Manna Yawm al-Ard (Land Day) 83 Khalil Nakhleh The Higher Follow-Up Committee for the Arab Citizens in Israel 90 Muhammad Amara Palestinian Political Prisoners 100 Abeer Baker National Priority Areas 110 Rassem Khamaisi The Indigenous Palestinian Bedouin of the Naqab: Forced Urbanization and Denied Recognition 120 Ismael Abu-Saad Palestinian Citizenship in Israel 128 Oren Yiftachel 3 Mada al-Carmel Arab Center for Applied Social Research Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to a group of colleagues who helped make possible the project of writing this book and producing it in three languages. -

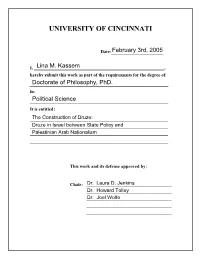

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ The Construction of Druze Ethnicity: Druze in Israel between State Policy and Palestinian Arab Nationalism A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Political Science of the College of Arts and Sciences 2005 by Lina M. Kassem B.A. University of Cincinnati, 1991 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 1998 Committee Chair: Professor Laura Jenkins i ABSTRACT: Eric Hobsbawm argues that recently created nations in the Middle East, such as Israel or Jordan, must be novel. In most instances, these new nations and nationalism that goes along with them have been constructed through what Hobsbawm refers to as “invented traditions.” This thesis will build on Hobsbawm’s concept of “invented traditions,” as well as add one additional but essential national building tool especially in the Middle East, which is the military tradition. These traditions are used by the state of Israel to create a sense of shared identity. These “invented traditions” not only worked to cement together an Israeli Jewish sense of identity, they were also utilized to create a sub national identity for the Druze. The state of Israel, with the cooperation of the Druze elites, has attempted, with some success, to construct through its policies an ethnic identity for the Druze separate from their Arab identity. -

Die Lokale Wahlen in Den Arabischen Und Duzen Stdten, 2008

Die Kommunalwahlen in den arabischen und drusischen Städten, 2008 - Ein Überblick Abstimmungsrate Die Wahlen am 11. November 2008 fanden in 159 Städten in Israel statt: - 56 arabische und drusische Städte - 102 jüdische und gemischte Städte - 1 tscherkessische Stadt Stimmenrate im arabischen und drusischen Sektor: 77.3% - Stimmenrate in ganz Israel: 46.2% - Stimmenrate im jüdischen Sektor: 42.1% Stimmenrate in der Kommunalwahlen der letzten 10 Jahre Jahr Araber und Drusen Israel allgemein 1998 90.7% 57.4% 2003 87.1% 49.3% 2008 77.3% 46.2% *Quelle: Angaben vom Innenministerium 1998, 2003, 2008 Im Vergleich - Stimmenrate in den Knessetwahlen der letzten 10 Jahre Jahr Araber und Drusen Israel allgemein 1996 77.0% 79.3% 1999 75.0% 78.7% 2003 62.9% 68.9% 2006 56.3% 63.2% *Quelle: Rekhess 2007 Gründe der Unterschiede: Die Wichtigkeit der Lokalpolitik im Vergleich zur Staatspolitik innerhalb der arabischen Bevölkerung in Israel Lokal Staatlich Starkes Zugehörigkeitsgefühl Entfremdungsgefühle dem Staat gegenüber Realisierung von lokalen Interessen Abwesenheit von staatlichen Einrichtungen (Erziehung, Soziales, Entwicklung usw.) Schwacher Status der arabischen Parteien Sehr hohe Abstimmungsrate – über 90% Kfar Bara - 94% Kfar Kassem – 93% Dir Hana – 93% Shaab – 92% Sachnin – 92% Mazraa – 91% Kabul – 91% Galgulia – 91% 30 Städte – zwischen 80% und 90% - Beduinen Städte (Rahat – 89%, Hura – 84%) - Drusen Städte (Gulis – 86%, Hurfesh – 87%) - Gemischte Städte (Pkiin – 87%, Abu Snan – 84%, Shfaram – 81%) - Muslimische Städte im „Triangel“-Gebiet (Kfar -

The Palestinians in Israel

Working Paper V The Role of Social Sorting and Categorization Under Exceptionalism in Controlling a National Minority: The Palestinians in Israel by Ahmad H. Sa’di∗ November 2011 ∗ Department of Politics & Government, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Introduction This report explores how surveillance and categorization were used by the state of Israel to control the Palestinian minority during the first two decades after Israel’s establishment in 1948. The methods of surveillance, which involve collection of data about the population, its storage, classification, and the categorization of citizens according to various organizing principles, have been essential tools for modern states in managing their populations. The collected data and its presentation through various statistical measures, which enhances the power of the state, may be used positively – to address the needs of the population efficiently, to target groups which are in need of special attention, to empower citizens – or negatively to subjugate or marginalize certain groups. Michel Foucault has famously argued that power is constitutive of the self, though he also maintained that power could have a positive or negative role. In the latter form it is used for domination. While the naïve perception of social groups as “natural” or as positioned around an interiority that sets them apart from others is disappearing, the recent research on surveillance, following Foucault, has focused on the role that power plays in the constitution of social categories and identities. Thus, social sorting, categorization and the construction of polarities are examined. This approach is employed in the first section of this report. In it, I shall probe the construction of the Palestinians as non-Jewish population and as a collection of ethnicities by exploring the historical origin of these categories and tracing their evolvement. -

Palestine - Israel Journal of Politic…

08/09/2009 Palestine - Israel Journal of Politic… The Palestine-Israel Journal is a quarterly of MIDDLE EAST PUBLICATIONS, a registered non-profit organization (No. 58-023862-4). V ol 1 5 N o. 4 & V ol 1 6 N o. 1, 0 8 /09 / The Refugee Question Focus Palestinian Internally Displaced Persons inside Israel: Challenging the Solid Structures The Palestinians who remained in Israel after 1948 have suffered displacement and dispossession by Nihad Boqa’i Palestinian internally displaced persons (IDPs) inside Israel are part of the larger Palestinian refugee population that was displaced/expelled from their villages and homes during the 1948 war in Palestine — the Nakba. While most of the refugees were displaced to the Arab states and the Palestinian territories that did not fall under Israeli control (i.e., the West Bank and the Gaza Strip), some 150,000 Palestinians Editorial Board remained in the areas of Palestine that became the state of Israel. Hisham Awartani This included approximately 30,000-40,000 Palestinians who were also displaced during the war. As in the case of the Palestinian Danny Rubinstein refugees who were displaced/expelled beyond the borders of the new Sam'an Khoury state, Israel refused to allow internally displaced Palestinians to return Boaz Evron to their homes and villages. Walid Salem Displacement did not end with the 1948 war. In the years following Ari Rath the establishment of Israel, internally displaced Palestinians, a small number of refugees who had returned spontaneously to their villages Zahra Khalidi and Palestinians who had not been displaced during the war were Daniel Bar-Tal expelled for security and other reasons. -

State Attitudes Towards Palestinian Christians in a Jewish Ethnocracy

Durham E-Theses State Attitudes towards Palestinian Christians in a Jewish Ethnocracy MCGAHERN, UNA How to cite: MCGAHERN, UNA (2010) State Attitudes towards Palestinian Christians in a Jewish Ethnocracy, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/128/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk State Attitudes towards Palestinian Christians in a Jewish Ethnocracy Una McGahern PhD in Political Science School of Government & International Affairs Durham University 2010 Abstract This thesis challenges the assumption of Israeli state bias in favour of its Palestinian Christian population. Using ethnocratic and control theories it argues instead that the Palestinian Christians are inextricably associated with the wider Arab “problem” and remain, as a result, permanently outside the boundaries of the dominant Jewish national consensus. Moreover, this thesis argues that state attitudes towards the small Palestinian Christian communities are quite unique and distinguishable from its attitudes towards other segments of the Palestinian Arab minority, whether Muslim or Druze. -

A B C Chd Dhe FG Ghhi J Kkh L M N P Q RS Sht Thu V WY Z Zh

Arabic & Fársí transcription list & glossary for Bahá’ís Revised September Contents Introduction.. ................................................. Arabic & Persian numbers.. ....................... Islamic calendar months.. ......................... What is transcription?.. .............................. ‘Ayn & hamza consonants.. ......................... Letters of the Living ().. ........................ Transcription of Bahá ’ı́ terms.. ................ Bahá ’ı́ principles.. .......................................... Meccan pilgrim meeting points.. ............ Accuracy.. ........................................................ Bahá ’u’llá h’s Apostles................................... Occultation & return of th Imám.. ..... Capitalization.. ............................................... Badı́‘-Bahá ’ı́ week days.. .............................. Persian solar calendar.. ............................. Information sources.. .................................. Badı́‘-Bahá ’ı́ months.. .................................... Qur’á n suras................................................... Hybrid words/names.. ................................ Badı́‘-Bahá ’ı́ years.. ........................................ Qur’anic “names” of God............................ Arabic plurals.. ............................................... Caliphs (first ).. .......................................... Shrine of the Bá b.. ........................................ List arrangement.. ........................................ Elative word -

In Occupied Jerusalem: Theodore “Teddy” Kollek, the Palestinians, and the Organizing Principles of Israeli Municipal Policy, 1967- 1987

‘Adjusting to Powerlessness’ in Occupied Jerusalem: Theodore “Teddy” Kollek, the Palestinians, and the Organizing Principles of Israeli Municipal Policy, 1967- 1987. By Oscar Jarzmik A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto © Copyright by Oscar Jarzmik 2016 ii ‘Adjusting to Powerless’ in Occupied Jerusalem: Theodore “Teddy” Kollek, the Palestinians, and the Organizing Principles of Israeli Municipal Policy, 1967-1987. Oscar Jarzmik Doctor of Philosophy Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto 2016 Abstract This dissertation examines the art of government on the part of the Israeli Municipality in Jerusalem by tracking its rationalization and implementation from the beginning of the occupation in June 1967 until the breakout of the first Palestinian intifada in December 1987. I argue that local policymakers assumed a uniqueness to the history and sociality of Jerusalem and posited a primordial set of political and cultural traditions among Palestinian residents. These preconceptions encouraged them to develop a particular structure for local government and concomitant blueprint for social/administrative relations. Architects of these policies were Mayor Theodore “Teddy” Kollek and an allied group of municipal functionaries who variously identified their policies as “national-pluralist,” “bi-cultural,” and “mosaic” oriented. They believed that an approach towards consolidating