Abui Landscape Names: Origin and Functions DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.51/2016/5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

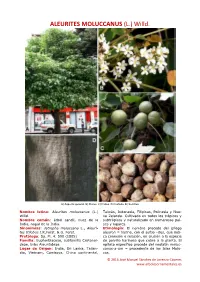

ALEURITES MOLUCCANUS (L.) Willd

ALEURITES MOLUCCANUS (L.) Willd. A) Aspecto general. B) Flores. C) Frutos. D) Corteza. E) Semillas Nombre latino: Aleurites moluccanus (L.) Taiwán, Indonesia, Filipinas, Polinesia y Nue- Willd. va Zelanda. Cultivado en todos los trópicos y Nombre común: árbol candil, nuez de la subtrópicos y naturalizado en numerosos paí- India, nogal de la India. ses y lugares. Sinonimias: Jatropha moluccana L., Aleuri- Etimología: El nombre procede del griego tes trilobus J.R.Forst. & G. Forst. aleuron = harina, con el sufijo –ites, que indi- Protólogo: Sp. Pl. 4: 590 (1805) ca conexión o relación, en alusión a la especie Familia: Euphorbiaceae, subfamilia Crotonoi- de polvillo harinoso que cubre a la planta. El deae, tribu Aleuritideae. epíteto específico procede del neolatín moluc- Lugar de Origen: India, Sri Lanka, Tailan- canus-a-um = procedente de las Islas Molu- dia, Vietnam, Camboya, China continental, cas. © 2016 José Manuel Sánchez de Lorenzo‐Cáceres www.arbolesornamentales.es Descripción: árbol siempreverde, monoico, obovoides, comprimidas dorsiventralmente, de 5-10 m de altura en cultivo, pudiendo al- de 2,3-3,2 x 2-3 cm, grisáceas con moteado canzar más de 30 en sus zonas de origen, con castaño. el tronco recto y la corteza lisa, grisácea o castaño rojiza, con lenticelas y fisurada con el Fenología: aunque dependiendo del clima paso del tiempo; copa frondosa, más o menos tiene flores y frutos gran parte del año, flore- piramidal, con las ramillas jóvenes puberulen- ce mayormente de Abril a Noviembre y fructi- tas, con indumento de pelos estrellados grisá- fica de Octubre a Diciembre, permaneciendo ceos o plateado-amarillentos, a veces algo los frutos en el árbol casi un año sin abrir, rojizos. -

Cosmetic Ingredients Found Safe As Used (1398 Total, Through February, 2012)

Cosmetic ingredients found safe as used (1398 total, through February, 2012) Ingredient # "As used" concentration for safe as used conclusion Acacia Senegal Gum and Acacia Senegal Gum Extract 2 up to 9% Acetic Acid 1 up to 0.3% Acetylated Lanolin 1 up to 7% Acetylated Lanolin Alcohol 1 up to 16% Acetyl Tributyl Citrate 1 up to 7% Acetyl Triethyl Citrate 1 up to 7% Acetyl Trihexyl Citrate 1 not in use at the time* Acetyl Trioctyl Citrate 1 not in use at the time* Acrylates/Dimethiconol Acrylate Copolymer (Dimethiconol and its Esters and Reaction Products) 1 up to 0.5% Actinidia Chinensis (Kiwi) Seed Oil 1 up to 0.1% Adansonia Digitata Oil 1 up to 0.01% Adansonia Digitata Seed Oil 1 not in use at the time* Adipic Acid (Dicarboxylic Acids and their Salts and Esters) 1 0.000001% in leave on; 18% in rinse off Alcohol Denat. denatured with t-Butyl Alcohol, Denatonium Benzoate, Diethyl Phthalate, or Methyl 4 up to 99% Alcohol Aleurites Moluccanus Bakoly Seed Oil 1 not in use at the time* Aleurities Moluccana Seed Oil 1 0.00001 to 5% Allantoin 1 up to 2% Allantoin Ascorbate 1 up to 0.05% Allantoin Biotin and Allantoin Galacturonic Acid 2 not in use at the time* Allantoin Glycyrrhetinic Acid, Allantoin Panthenol, and Allantoin Polygalacturonic Acid 3 concentration not reported* Almond Meal (aka- Prunus Amygdalus Dulcis) Alumnina Magnesium Silicate 1 up to 0.01% Alumnium Calcium Silicate 1 up to 6% Aluminum Dimyristate 1 up to 3% Aluminum Distearate 1 up to 5% Aluminum Iron Silicates 1 not in use at the time* Aluminum Isostearates/Myristates, Calcium -

Theobroma Cacao

International Journal of Scientific Research and Management (IJSRM) ||Volume||09||Issue||02||Pages||AH-2021-330-344||2021|| Website: www.ijsrm.in ISSN (e): 2321-3418 DOI: 10.18535/ijsrm/v9i02.ah01 Disease prevalence and shade tree diversity in smallholder cocoa (Theobroma cacao) farms: case of Bundibugyo District, Western Uganda Blasio Bisereko Bwambale1, Godfrey Sseremba1,2, Julius Mwine1 1Faculty of Agriculture, Uganda Martyrs University, P.O. Box 5498, Kampala, Uganda 2National Coffee Research Institute, National Agricultural Research Organization, P.O. Box 185, Mukono, Uganda Abstract Cocoa (Theobroma cacao) growing systems in Uganda consists of shade systems with different tree species. Tree shade systems are the pure stand trees in the cocoa plantation which have been attributed to wards reducing on pests and disease incidences, shade provision, boosting fertility, Agro biodiversity, fodder and improving production. The study was aimed at identifying potential shade tree species that can minimize disease threats on cocoa farms. Eighty-two cocoa farmers were reached out of 120 cocoa farmers in Bundibugyo that possessed at least five acres of the plantation in a purposive sampling approach. Black pod disease was non-significantly associated with presence of shade tree diversities. It was established that incidence of black pod rot disease was non-significantly associated with presence of all shade tree species; association between witch’s broom disease incidence with presence of Maesopsis eminii was highly significant (χ2= 55.41, (p<0.05); Association between witch’s broom and presence of Persea Americana(χ2=9.79), (p<0.05), Eucalyptus globulus (χ2=16.71), (p<0.05), Markhamia obtusifolia (χ2=3.95),(p<0.001), schefflera actinophylla (χ2=4.32), (p<0.001), Mangifera indica (χ2=6.46), (p<0.001) was significant though these trees were planted in small numbers. -

Federal Register/Vol. 77, No. 163/Wednesday

50622 Federal Register / Vol. 77, No. 163 / Wednesday, August 22, 2012 / Rules and Regulations CROP GROUP 14–12: TREE NUT GROUP—Continued Bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa Michx.) Butternut (Juglans cinerea L.) Cajou nut (Anacardium giganteum Hance ex Engl.) Candlenut (Aleurites moluccanus (L.) Willd.) Cashew (Anacardium occidentale L.) Chestnut (Castanea crenata Siebold & Zucc.; C. dentata (Marshall) Borkh.; C. mollissima Blume; C. sativa Mill.) Chinquapin (Castaneapumila (L.) Mill.) Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) Coquito nut (Jubaea chilensis (Molina) Baill.) Dika nut (Irvingia gabonensis (Aubry-Lecomte ex O’Rorke) Baill.) Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba L.) Guiana chestnut (Pachira aquatica Aubl.) Hazelnut (Filbert) (Corylus americana Marshall; C. avellana L.; C. californica (A. DC.) Rose; C. chinensis Franch.) Heartnut (Juglans ailantifolia Carrie`re var. cordiformis (Makino) Rehder) Hickory nut (Carya cathayensis Sarg.; C. glabra (Mill.) Sweet; C. laciniosa (F. Michx.) W. P. C. Barton; C. myristiciformis (F. Michx.) Elliott; C. ovata (Mill.) K. Koch; C. tomentosa (Lam.) Nutt.) Japanese horse-chestnut (Aesculus turbinate Blume) Macadamia nut (Macadamia integrifolia Maiden & Betche; M. tetraphylla L.A.S. Johnson) Mongongo nut (Schinziophyton rautanenii (Schinz) Radcl.-Sm.) Monkey-pot (Lecythis pisonis Cambess.) Monkey puzzle nut (Araucaria araucana (Molina) K. Koch) Okari nut (Terminalia kaernbachii Warb.) Pachira nut (Pachira insignis (Sw.) Savigny) Peach palm nut (Bactris gasipaes Kunth var. gasipaes) Pecan (Carya illinoinensis (Wangenh.) K. Koch) Pequi (Caryocar brasiliense Cambess.; C. villosum (Aubl.) Pers; C. nuciferum L.) Pili nut (Canarium ovatum Engl.; C. vulgare Leenh.) Pine nut (Pinus edulis Engelm.; P. koraiensis Siebold & Zucc.; P. sibirica Du Tour; P. pumila (Pall.) Regel; P. gerardiana Wall. ex D. Don; P. monophylla Torr. & Fre´m.; P. -

Kilauea Community Ag. Park Tree List, Alphabeticly

Kilauea Community Ag. Park Tree list, Alphabeticly Tree List for Kilauea Lighthouse Road A# KCAC name map # tag Scientifis name Family Hawaiian name Common name Origin fruit / use flower 1 Abiu 68 Pouteria caimito Sapotaceae Amazonian So. Am. tasty fruit 1,2,2.5,3,8,11,12, 2 Acacia Grande (Caro, carao) Cassia grandis FaBaceae Pink shower tree Amazonian So. Am. 16,24,25 3 Artocarpus altilis 61 Artocarpus altilis Moraceae Ulu Breadfruit New Guinea 4 Artocarpus hetaophyllus 30 Artocarpus hetaophyllus Moraceae Hua Jackfruit SE asia 5 Avocado 29 Persea americana Lauraceae Kahalu'u Avocado southern Mexico 6 Avocado, Malama 47 Persea americana Lauraceae Avocado horticultural selections 7 Avocado, Ota 51 Persea americana Lauraceae Avocado horticultural selections 8 Avocado, Sharwil 55 Persea americana Lauraceae Avocado horticultural selections 9 Banana 31,36,38,40,42 Musa sapientum Moraceae banana Indomalaya, Australia 10 Caesalpinia (syn. Sesalpinya) see 33 Caesalpinia ??? FaBaceae peacock flower tropical Americas 11 Cashew 44B Anacardium occidentale Anacardiaceae Akakiu Cashew Cent. Am. & CariBBean 12 Cassia Grandis 27 Cassia grandis FaBaceae Pink shower tree Mex, Ven, Ecuador 13 Chorisia Speciosa 22,32 Ceiba speciosa Malvaceae Floss silk tree So. America 14 Dragon fruit 66 Hylocereus undatus Cactaceae Papipi Pua Dragon fruit not resolved 15 Ecuador Laurel 14,20,23 Cordia alliodora Boraginaceae Ecuador Laurel So. america 16 Fig 34C Ficus carica Moraceae Piku Fig Middle East & W. Asia 17 Ice Cream tree 4 Inga feuillei FaBaceae Ice Cream tree Andean valleys, So. Am. 18 Kaimana Lychee 43 Litchi chinensis Sapindaceae Laiku Lychee Guangdong, China 19 Kava 53A Piperaceae methysticum Poperaceae Awa Kava Pacific Islands 20 Koa l'a 18 Acacia koa FaBaceae Koa Koa Hawaii, endimic 21 Kukui (Behind office) 62 Aleurites moluccanus EuphorBiaceae Candlenut Southeast Asia 22 Lime 54 Citrus latifolia Rutaceae Lemi Tahiti lime hybrid, horticultural origin 23 Lophantera (sp) 7,17 Lophanthera lactescens Malpighiaceae Golden Chain Tree Amazonian So. -

Mango Fruit Fly, Bactrocera Frauenfeldi, Host List the Berries, Fruits, Nuts and Vegetables of the Listed Plant Species Are Now Considered Host Articles for B

January 2018 Mango fruit fly, Bactrocera frauenfeldi, Host List The berries, fruits, nuts and vegetables of the listed plant species are now considered host articles for B. frauenfeldi. Unless proven otherwise, all cultivars, varieties, and hybrids of the plant species listed herein are considered suitable hosts of B. frauenfeldi. Scientific Name Common Name Aleurites moluccanus (L.) Willd. Candlenut Anacardium occidentale L. Cashew Annona glabra L. Pond-apple Annona muricata L. Soursop Annona reticulata L. Custard-apple Annona squamosa L. Sweetsop Artocarpus altilis (Parkinson) Fosberg Breadfruit Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam. Jackfruit Artocarpus mariannensis Trecul N/A Averrhoa carambola L. Carambola Baccaurea papuana F.M. Bailey N/A Barringtonia calyptrocalyx K. Schum. N/A Barringtonia edulis Seem. N/A Broussonetia papyrifera (L.) Vent. Paper-mulberry Burckella obovata (G. Forst.) Pierre N/A Calophyllum inophyllum L. Alexandrian laurel Calophyllum peekelii Lauterb. N/A Calophyllum spp. N/A Cananga odorata (Lam.) Hook. F. & Thomson Ylang-ylang tree Carica papaya L. Papaya Cerbera manghas L. Sea-mango Chrysophyllum cainito L. Star-apple Citrofortunella microcarpa (Bunge) Wijnands Calamondin Citrus aurantium L. Sour orange Citrus limetta Risso Sweet lime Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr. Pummelo Citrus paradisi Macfad. Grapefruit Citrus reticulata Blanco Mandarin Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck Orange Citrus sp. Citrus1 Clymenia polyandra (Tanaka) Swingle Clymenia Diospyros digyna Jacq. Black persimmon Diospyros ebenum J. Koenig Ebony persimmon Oriental Diospyros kaki Thunb. persimmon Diospyros nigra (J.F. Gmel.) Perr. N/A Argus pheasant- Dracontomelon dao (Blanco) Merr. & Rolfe tree Eugenia reinwardtiana (Blume) DC. Cedar Bay-cherry Eugenia uniflora L. Surinam cherry Ficus carica L. Fig Ficus glandulifera Wall. N/A Ficus leptoclada Benth. -

Ecological Approach on Sanitation

Jurnal Bumi Lestari, Volume 19, Nomor 1, Tahun 2018, Halaman 15-19 Ethnobotany Study Of Communities Of Forest Area Around Buyan And Tamblingan Lake, Buleleng, Bali I. D. P. Darma a*, Arief Priyadi a, Gebby A. E. Oktavia a a Bali Botanical Garden, Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) Candikuning, Baturiti, Tabanan, Bali 82191 *Email: [email protected] Diterima (received) 4 April 2018; disetujui (accepted) 31 Januari 2019; tersedia secara online (available online) 1 Februari 2019 Abstrak Mayoritas masyarakat sekitar kawasan hutan danau Buyan dan Tamblingan memeluk agama Hindu. Masyarakat memanfaatkan tumbuhan dalam berbagai kepentingan, sehingga mereka memiliki peran penting untuk menjaga dan melestarikan keanekaragaman tumbuhan di sekitarnya. Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk mengetahui pemanfaatan tumbuhan oleh masyarakat Bali di sekitar kawasan hutan danau Buyan dan Tamblingan. Metode dalam penelitian ini adalah wawancara. Hasil menunjukkan bahwa terdapat 181 jenis tumbuhan yang dimanfaatkan oleh masyarakat untuk 11 jenis tujuan pemanfaatan. Kata Kunci: studi etnobotani; masyarakat; kawasan hutan Danau Buyan dan Tamblingan; pemanfaatan tumbuhan 1. Preface Forest area around Buyan and Tamblingan lake is one of tourist area and water catchment area for South and North Bali community (Badung, Denpasar, Tabanan and Buleleng) (Suji, 2005). This area is upstream region of Catur Angga Batukaru which is regarded as a sacred place by Balinese people. Conservation of this area is important for preservation of Subak Jatiluwih as a UNESCO World Heritage (Windia and Wiguna, 2013). Biosphere Reserve Concept has been proposed at The Symposium on Analysis of Water Carrying Capacity in Beratan, Buyan and Tamblingan lakes area, Bali which was organized by Bali Botanical Garden – Indonesian Institute of Science and Bali Regional Environmental Impact Management Agency in 2005. -

HAWAII and SOUTH PACIFIC ISLANDS REGION - 2016 NWPL FINAL RATINGS U.S

HAWAII and SOUTH PACIFIC ISLANDS REGION - 2016 NWPL FINAL RATINGS U.S. ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS, COLD REGIONS RESEARCH AND ENGINEERING LABORATORY (CRREL) - 2013 Ratings Lichvar, R.W. 2016. The National Wetland Plant List: 2016 wetland ratings. User Notes: 1) Plant species not listed are considered UPL for wetland delineation purposes. 2) A few UPL species are listed because they are rated FACU or wetter in at least one Corps region. Scientific Name Common Name Hawaii Status South Pacific Agrostis canina FACU Velvet Bent Islands Status Agrostis capillaris UPL Colonial Bent Abelmoschus moschatus FAC Musk Okra Agrostis exarata FACW Spiked Bent Abildgaardia ovata FACW Flat-Spike Sedge Agrostis hyemalis FAC Winter Bent Abrus precatorius FAC UPL Rosary-Pea Agrostis sandwicensis FACU Hawaii Bent Abutilon auritum FACU Asian Agrostis stolonifera FACU Spreading Bent Indian-Mallow Ailanthus altissima FACU Tree-of-Heaven Abutilon indicum FAC FACU Monkeybush Aira caryophyllea FACU Common Acacia confusa FACU Small Philippine Silver-Hair Grass Wattle Albizia lebbeck FACU Woman's-Tongue Acaena exigua OBL Liliwai Aleurites moluccanus FACU Indian-Walnut Acalypha amentacea FACU Alocasia cucullata FACU Chinese Taro Match-Me-If-You-Can Alocasia macrorrhizos FAC Giant Taro Acalypha poiretii UPL Poiret's Alpinia purpurata FACU Red-Ginger Copperleaf Alpinia zerumbet FACU Shellplant Acanthocereus tetragonus UPL Triangle Cactus Alternanthera ficoidea FACU Sanguinaria Achillea millefolium UPL Common Yarrow Alternanthera sessilis FAC FACW Sessile Joyweed Achyranthes -

The One Hundred Tree Species Prioritized for Planting in the Tropics and Subtropics As Indicated by Database Mining

The one hundred tree species prioritized for planting in the tropics and subtropics as indicated by database mining Roeland Kindt, Ian K Dawson, Jens-Peter B Lillesø, Alice Muchugi, Fabio Pedercini, James M Roshetko, Meine van Noordwijk, Lars Graudal, Ramni Jamnadass The one hundred tree species prioritized for planting in the tropics and subtropics as indicated by database mining Roeland Kindt, Ian K Dawson, Jens-Peter B Lillesø, Alice Muchugi, Fabio Pedercini, James M Roshetko, Meine van Noordwijk, Lars Graudal, Ramni Jamnadass LIMITED CIRCULATION Correct citation: Kindt R, Dawson IK, Lillesø J-PB, Muchugi A, Pedercini F, Roshetko JM, van Noordwijk M, Graudal L, Jamnadass R. 2021. The one hundred tree species prioritized for planting in the tropics and subtropics as indicated by database mining. Working Paper No. 312. World Agroforestry, Nairobi, Kenya. DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.5716/WP21001.PDF The titles of the Working Paper Series are intended to disseminate provisional results of agroforestry research and practices and to stimulate feedback from the scientific community. Other World Agroforestry publication series include Technical Manuals, Occasional Papers and the Trees for Change Series. Published by World Agroforestry (ICRAF) PO Box 30677, GPO 00100 Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254(0)20 7224000, via USA +1 650 833 6645 Fax: +254(0)20 7224001, via USA +1 650 833 6646 Email: [email protected] Website: www.worldagroforestry.org © World Agroforestry 2021 Working Paper No. 312 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of World Agroforestry. Articles appearing in this publication series may be quoted or reproduced without charge, provided the source is acknowledged. -

Introduction to the Papuan Languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar. Volume III Antoinette Schapper

Introduction to The Papuan languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar. Volume III Antoinette Schapper To cite this version: Antoinette Schapper. Introduction to The Papuan languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar. Volume III. Antoinette Schapper. Papuan languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar. Sketch grammars, 3, De Gruyter Mouton, pp.1-52, 2020. halshs-02930405 HAL Id: halshs-02930405 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02930405 Submitted on 4 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License Introduction to The Papuan languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar. Volume III. Antoinette Schapper 1. Overview Documentary and descriptive work on Timor-Alor-Pantar (TAP) languages has proceeded at a rapid pace in the last 15 years. The publication of the volumes of TAP sketches by Pacific Linguistics has enabled the large volume of work on these languages to be brought together in a comprehensive and comparable way. In this third volume, five new descriptions of TAP languages are presented. Taken together with the handful of reference grammars (see Section 3), these volumes have achieved descriptive coverage of around 90% of modern-day TAP languages. -

Abui Stokhof, W

CURRENT STATUS OF LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION IN THE ALOR ARCHIPELAGO František KRATOCHVÍL Nanyang Technological University 1 Friday, February 17, 12 OUTLINE OF THE PAPER Introduction Early sources (1500-1950) • Pigafetta (1512) • Dutch administrators and travellers (Van Galen) • Cora Du Bois and M. M. Nicolspeyer (1930’s) 1970’s • Stokhof and Steinhauer 2000+’s • Mark Donohue (1997, 1999), Doug Marmion (fieldwork on Kui), Asako Shiohara (Kui) • Haan 2001 (U of Sydney) • Linguistic Variation in Eastern Indonesia project • Gary Holton • EuroBabel project 2 Friday, February 17, 12 GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION 3 Friday, February 17, 12 LINGUISTIC SITUATION (NOT SUPPORTED IN HOLTON ET AL. 2012) 4 Friday, February 17, 12 LINGUISTIC SITUATION 5 Friday, February 17, 12 Introduction Synchronic distribution Linguistic Situation Diachronic development Historical profile Discussion and Conclusion Typological profile References Historical characteristics of AP group LINGUISTIC SITUATION 1. Papuan outlier (some 1000 km from the New Guinea mainland) 2. tentatively linked with Trans New Guinea (TNG) family - western Bomberai peninsula languages (Ross 2005) based on pronominal evidence >>> not supported in Holton et al 2012 3. small languages (max. 20,000 speakers, some < 1,000) 4. surrounded by Austronesian languages 5. long history of genetic admixture (Mona et al. 2009) 6. possibly long-lasting language contact and linguistic convergence (Holton et al. to appear) Frantiöek Kratochvíl et al. Pronominal systems in AP languages 8/77 6 Friday, February 17, 12 Introduction Synchronic distribution Linguistic Situation Diachronic development Historical profile Discussion and Conclusion Typological profile References Grammatical characteristicsLINGUISTIC CHARACTERISTICS of the AP group 1. head-final and head-marking 2. great variation in alignment types: ranging from nom-acc (Haan 2001; Klamer 2010) to fluid semantic alignment (Klamer 2008; Donohue and Wichmann 2008; Kratochvíl to appear; Schapper 2011b) 3. -

Documentation of Western Pantar (Lamma) an Endangered Language of Pantar Island, NTT, Indonesia

Documentation of Western Pantar (Lamma) an endangered language of Pantar Island, NTT, Indonesia Item Type Report Authors Holton, Gary Publisher Lembaga Ilmu Pengatahun Indonesia [ = Indonesian Academy of Sciences] Download date 10/10/2021 08:10:56 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/6807 Documentation of Western Pantar (Lamma) an endangered language of Pantar Island, NTT, Indonesia Tentative Final Research Report period 20 August 2006 – 19 August 2007 submitted to Lembaga Ilmu Pengatahuan Indonesia (LIPI) Date submitted: 27 June 2007 Prepared by: Dr. Gary Michael Holton Associate Professor of Linguistics University of Alaska Fairbanks [email protected] Documentation of Western Pantar (Lamma) an endangered language of Pantar Island, NTT, Indonesia Tentative Final Research Report Abstract This research project carried out linguistic documentation of Western Pantar, an endangered Papuan language spoken on Pantar Island, Nusa Tenggara Timur. The primary product of this research is an annotated corpus of audio and video recordings covering a range of genre and speech styles. All field data has been archived digitally following current best practice recommendations. Secondary products include a tri-lingual dictionary and a reference grammar. The use of aligned text and audio and the publication of a media corpus will ensure the future researchers have maximal access to original field data. The Pantar region remains one of the least documented linguistic areas in Indonesia, and almost no documentary information has previously been available for Western Pantar and many of the other non-Austronesian languages of Pantar. Through the use of best-practice language documentation techniques to create an enduring record of the language, the documentation produced by this project will broadly impact linguistic science, providing crucial typological data from a little-known part of the world’s linguistic landscape.