East-West Convergence Or Divergence?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Similarities and the Differences in the Functioning of the European Right Wing: an Attempt to Integrate the European Conservatives and Christian Democrats

Journal of Social Welfare and Human Rights, Vol. 1 No. 2, December 2013 1 The Similarities and the Differences in the Functioning of the European Right Wing: An Attempt to Integrate the European Conservatives and Christian Democrats Dr. Kire Sarlamanov1 Dr. Aleksandar Jovanoski2 Abstract The text reviews the attempt of the European Conservative and Christian Democratic Parties to construct a common platform within which they could more effectively defend and develop the interests of the political right wing in the European Parliament. The text follows the chronological line of development of events, emphasizing the doctrinal and the national differences as a reason for the relative failure in the process of unification of the European right wing. The subcontext of the argumentation protrudes the ideological, the national as well as the religious-doctrinal interests of some of the more important Christian Democratic, that is, conservative parties in Europe, which emerged as an obstacle of the unification. One of the more important problems that enabled the quality and complete unification of the European conservatives and Christian Democrats is the attitude in regard to the formation of EU as a federation of countries. The weight down of the British conservatives on the side of the national sovereignty and integrity against the Pan-European idea for united European countries formed on federal basis, is considered as the most important impact on the unification of the parties from the right ideological spectrum on European land. Key words: Conservative Party, Christian Democratic Party, CDU European Union, European People’s Party. 1. Introduction On European land, the trend of connection of political parties on the basis of ideology has been notable for a long time. -

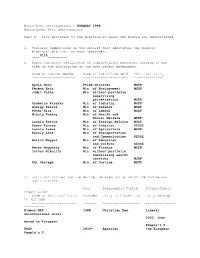

HUNGARY 1998 Macro-Level Data Questionnaire Part I: Data Pertinent

Macro-Data Questionnaire - HUNGARY 1998 Macro-Level Data Questionnaire Part I: Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1. Variable number/name in the dataset that identifies the primary electoral district for each respondent. ____V114__________ 2. Names and party affiliation of cabinet-level ministers serving at the time of the dissolution of the most recent government. Name of Cabinet Member Name of the Office Held Political Party ---------------------- ----------------------- --------------- Gyula Horn Prime Minister MSZP Ferenc Baja Min. of Environment MSZP Judit Csiha Min. without portfolio supervising privatization MSZP Szabolcs Fazakas Min. of Industry MSZP Gyorgy Keleti Min. of Defence MSZP Peter Kiss Min. of Labour MSZP Mihaly Kokeny Min. of Health and Social Welfare MSZP Laszlo Kovacs Min. of Foreign Affairs MSZP Gabor Kuncze Min. of Interior SZDSZ Laszlo Lakos Min. of Agriculture MSZP Karoly Lotz Min. of Transportation and Communication SZDSZ Balint Magyar Min. of Education and Culture SZDSZ Peter Megyessy Min. of Finance MSZP Istvan Nikolits Min. without portfolio supervising secret services MSZP Pal Vastagh Min. of Justice MSZP 3. Political Parties (active during the election at which the module was administered). Year Ideological Family International Organization Name of Political Party Founded Party is Closest to Party Belongs to (if any) ----------------------- ------- ------------------- ---------------- ---------- Fidesz-MPP 1988 Christian Dem. Liberal International until 2000, then moved to European People's P. FKGP 1930* Agrarian the European People's P. suspended the FKGP's membership in 1992 KDNP 1988 Christian Dem. The European People's P. suspended the KDNP's membership in 1997 MDF 1988 Christian Dem. European People's P. -

Ess4 - 2008 Documentation Report

ESS4 - 2008 DOCUMENTATION REPORT THE ESS DATA ARCHIVE Edition 5.5 Version Notes, ESS4 - 2008 Documentation Report ESS4 edition 5.5 (published 01.12.18): Applies to datafile ESS4 edition 4.5. Changes from edition 5.4: Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. 25 Version notes. Information updated for ESS4 ed. 4.5 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS4 ed. 4.5 data. Israel: 46 Deviations amended. Deviation in F1-F4 (HHMMB, GNDR-GNDRN, YRBRN-YRBRNN, RSHIP2-RSHIPN) added. Appendix: Appendix A3 Variables and Questions and Appendix A4 Variable lists have been replaced with Appendix A3 Codebook. ESS4 edition 5.4 (published 01.12.16): Applies to datafile ESS4 edition 4.4. Changes from edition 5.3: 25 Version notes. Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.4 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.4 data. Slovenia: 46 Deviations. Amended. Deviation in B15 (WRKORG) added. Appendix: A2 Classifications and Coding standards amended for EISCED. A3 Variables and Questions amended for EISCED, WRKORG. Documents: Education Upgrade ESS1-4 amended for EISCED. ESS4 edition 5.3 (published 26.11.14): Applies to datafile ESS4 edition 4.3 Changes from edition 5.2: All links to the ESS Website have been updated. 21 Weighting: Information regarding post-stratification weights updated. 25 Version notes: Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.3 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.3 data. Lithuania: ESS4 - 2008 Documentation Report Edition 5.5 2 46 Deviations. -

«Poor Family Name», «Rich First Name»

ENCIU Ioan (S&D / RO) Manager, Administrative Sciences Graduate, Faculty of Hydrotechnics, Institute of Construction, Bucharest (1976); Graduate, Faculty of Management, Academy of Economic Studies, Bucharest (2003). Head of section, assistant head of brigade, SOCED, Bucharest (1976-1990); Executive Director, SC ACRO SRL, Bucharest (1990-1992); Executive Director, SC METACC SRL, Bucharest (1992-1996); Director of Production, SC CASTOR SRL, Bucharest (1996-1997); Assistant Director-General, SC ACRO SRL, Bucharest (1997-2000); Consultant, SC GKS Special Advertising SRL (2004-2008); Consultant, SC Monolit Lake Residence SRL (2008-2009). Vice-President, Bucharest branch, Romanian Party of Social Solidarity (PSSR) (1992-1994); Member of National Council, Bucharest branch Council and Sector 1 Executive, Social Democratic Party of Romania (PSDR) (1994-2000); Member of National Council, Bucharest branch Council and Bucharest branch Executive and Vice-President, Bucharest branch, Social Democratic Party (PSD) (2000-present). Local councillor, Sector 1, Bucharest (1996-2000); Councillor, Bucharest Municipal Council (2000-2001); Deputy Mayor of Bucharest (2000-2004); Councillor, Bucharest Municipal Council (2004-2007). ABELA BALDACCHINO Claudette (S&D / MT) Journalist Diploma in Social Studies (Women and Development) (1999); BA (Hons) in Social Administration (2005). Public Service Employee (1992-1996); Senior Journalist, Newscaster, presenter and producer for Television, Radio and newspaper' (1995-2011); Principal (Public Service), currently on long -

Draft List of Invittees

FORUM ON NEW SECURITY ISSUES: “SHARED INTERESTS & VALUES BETWEEN SOUTHEASTERN EUROPE & THE TRANSATLANTIC COMMUNITY" (FONSI) WORKSHOP V: KOSOVO: SEEKING A SUSTAINABLE STATUS A workshop organised by The Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP) with the support of The German Marshall Fund of the US (GMFUS) and the NATO's Public Diplomacy Division Thessaloniki, 4-6 March 2005 List of Participants AFENTOULI Ino (Ms.), Information Officer, NATO Public Diplomacy Division, Brussels e-mail: [email protected] Despina-Ino Afentouli works as Information Officer at NATO’s Public Diplomacy Division. In this capacity she is in charge of information activities in Greece and regional coordinator for the Caucasus. In addition, she is responsible of the Academic Affairs Program, sponsored by PDD. She studied Law at the Athens University and earned a MA in Political Communication at Paris-I (Sorbonne). Before joining NATO she worked for fifteen years as a journalist specialising in Foreign Policy and European Affairs. She was Diplomatic Editor at the Athens News Agency, responsible for the Greek edition of the Economist Intelligence Unit and political correspondent at KATHIMERINI daily. As Secretary General of the European Network of Women Journalists has participated in many activities aiming at the rapprochement of media professionals in Southeastern Europe. She was also very active in Greek-Turkish rapprochement initiatives. For her work related with European Affairs she received the Calligas Award of the European Association of Journalists (Nov. 2000). ANTONATOS Panayotis (Mr.), Desk Officer for Kosovo, A3 Directorate, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Athens e-mail: [email protected] Born on the 15th of December, 1973 in Athens. -

European Union Foreign Affairs Journal

European Union Foreign Affairs Journal eQuarterly for European Foreign, Foreign Trade, Development, Security Policy, EU-Third Country Relations and Regional Integration (EUFAJ) N° 01/02 – 2013 ISSN 2190-6122 Contents Editorial...................................................................................................................................... 4 The Transformation of the Ethnic Minority Political Parties in Post-communist Europe: The Example of the Albanian Minority in Macedonia, compared with the Hungarian Minority in Slovakia Josipa Rizankoska ...................................................................................................................... 5 Racial Discrimination, Deprivation, Segregation and Marginalisation as a Reinforcement of the Practice of Child Marriage Rita Sorina Sein ..................................................................................................................... 110 Canadian First Nations: Elders Telling Stories Sitting in a Circle Walter Bonaise ....................................................................................................................... 141 Immigration and Security: Should Migration be a Securitization Issue? Tsoghik Khachatryan ............................................................................................................. 156 UNCTAD Acknowledges Admission of South Sudan as Forty-Ninth Least Developed Country (LDC) .................................................................. 164 The Role of Non-State Actors in Ensuring -

The Eastward Enlargement of European Parties: Party Adaptation in the Light of EU Enlargement

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271485672 The Eastward Enlargement of European Parties: Party Adaptation in the Light of EU enlargement Thesis · June 2013 CITATIONS READS 12 72 1 author: Mats Öhlén Dalarna University 18 PUBLICATIONS 19 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: European party families and ideological convergence between East- and West European member parties View project Interkulturellt utvecklingscentrum Dalarna - IKUD View project All content following this page was uploaded by Mats Öhlén on 04 March 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. The Eastward Enlargement of European Parties: Party Adaptation in the Light of EU-enlargement To my mother Örebro Studies in Political Science 31 MATS ÖHLÉN The Eastward Enlargement of European Parties Party Adaptation in the Light of EU-enlargement © Mats Öhlén, 2013 Title: The Eastward Enlargement of European Parties: Party Adaptation in the Light of EU-enlargement. Publisher: Örebro University 2013 www.publications.oru.se [email protected] Print: Örebro University, Repro 04/2013 ISSN 1650-1632 ISBN 978-91-7668-938-7 Abstract Mats Öhlén (2013): The Eastward Enlargement of European Parties: Party Adaptation in the Light of EU-enlargement. Örebro Studies in Political Science 31, 353 pp. The aim of the study is to map out and analyse the integration of political parties from Central and Eastern Europe into the main European party families. The prospect of eastern enlargement of the EU implicated oppor- tunities and above all challenges for the West European party families. -

Wilfried Loth Building Europe

Wilfried Loth Building Europe Wilfried Loth Building Europe A History of European Unification Translated by Robert F. Hogg An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-042777-6 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-042481-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-042488-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image rights: ©UE/Christian Lambiotte Typesetting: Michael Peschke, Berlin Printing: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Table of Contents Abbreviations vii Prologue: Churchill’s Congress 1 Four Driving Forces 1 The Struggle for the Congress 8 Negotiations and Decisions 13 A Milestone 18 1 Foundation Years, 1948–1957 20 The Struggle over the Council of Europe 20 The Emergence of the Coal and Steel Community -

Europa Und Die Deutsche Einheit. Beobachtungen, Entscheidungen

Michael Gehler and Hannes Schönner The European Democrat Union and the Revolutionary Events in Central Europe in 1989 First, this article will explain the role of the “European Democrat Union” (EDU) within the framework of European Christian Democrats and Conservatives and its importance for the year of change 1989. Second, it will touch on a few aspects on the leading figures; third, on the promising contacts between the EDU and the Communist Party of the USSR; fourth, on the role played by the EDU in Central Europe, especially vis-à-vis the events in Poland and Hungary, which were its priorities; and finally, on the developments in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) regarding the German Question.1 I. The Origins of the European Christian Democrats and Conservatives After 1945, Catholic-conservative and Christian democratic people’s parties played an increasingly more important role in Western Europe than before. There was no lack of new incentives nor of necessary challenges for transnational contacts and organized party cooperation. Nevertheless, the secret meetings of the “Geneva Circle” (1947–56) as well as cooperation within the “Nouvelles Equipes Internationales” (NEI), which were formed in 1947,2 up through their renaming and transformation into the “European Union of Christian Demo- crats” (EUCD) in 1965, were characterized by continuous debates about how far the coordination should go in both political and ideological matters.3 1 Due to the contribution by Michael Gehler, this chapter is—in part—a result of the FWF- project P 26439-G15 “Aktenedition: Österreich und die Deutsche Frage 1987 bis 1990.” 2 Michael Gehler, Der „Genfer Kreis“: Christdemokratische Parteienkooperation und Ver- trauensbildung im Zeichen der deutsch-französischen Annäherung 1947–1955, in: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft 49 (2001) 7, 599–625; id., The Geneva Circle of West European Christian Democrats, in: Michael Gehler/Wolfram Kaiser, Christian Democracy in Europe since 1945, Vol. -

Level Data Part I

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Macro – Level Data Part I: Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1. Variable number/name in the data set that identifies the primary electoral district for each respondent. ______________________________ 2. Names and party affiliation of cabinet-level ministers serving at the time of the dissolution of the most recent government. Name of Cabinet Member Name of the Office Held Political Party 3. Political Parties (active during the election at which the module was administered). Name of Political Party Year Ideological Family International Organization Founded Party is Closest to Party Belongs to (if any) Perú 2000 1990 Independents None Perú Posible 1999 Independents None Unión por el Perú 1995 Independents None Frente Independiente Moralizador 1990 Anti corruption None Avancemos 1999 Independents None Acción Popular 1952 Independents None Somos Perú 1996 Independents None Alianza Popular Revolucionaria 1926 Social Democratic Socialist International Americana (APRA) Parties Solidaridad Nacional 1999 Independents None FREPAP 1980 Ethnic Parties None Ideological Party Families: Ecology Parties Liberal Parties Agrarian Parties Communist Parties Right Liberal Parties Ethnic Parties Socialist Parties Christian Democratic Regional Parties Social Democratic Parties Conservative Parties Other Parties Left Liberal Parties National Parties Independents International Party Organizations: Socialist International Confederation of Socialist Parties of the European Community Asia Pacific Socialist Organization Socialist Inter African Liberal International Federation of European Liberal, Democrat and Reform Parties Christian Democratic International European Christian Democratic Union European People’s Party International Democrat Union Caribbean Democrat Union European Democrat Union Pacific Democrat Union The Greens 4. (a) Parties position in left-right scale (in the expert judgement of the CSES Collaborator): Party Name Left Right 1. -

KM Avhandling F Rdig

Transnational Party Alliances Analysing the Hard-Won Alliance Between Conservatives and Christian Democrats in the European Parliament Johansson, Karl Magnus 1997 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Johansson, K. M. (1997). Transnational Party Alliances: Analysing the Hard-Won Alliance Between Conservatives and Christian Democrats in the European Parliament. Lund University Press. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 TRANSNATIONAL PARTY ALLIANCES 1 2 TRANSNATIONAL PARTY ALLIANCES ANALYSING THE HARD-WON ALLIANCE BETWEEN CONSERVATIVES AND CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATS IN THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT n Karl Magnus Johansson 3 Lund University Press Box 141 SE-221␣ 00 Lund © Karl Magnus Johansson 1997 Art. -

The Evolution of the European People's Party After the Integration of Parties from Western and Eastern Europe. Lessons to B

Πανεπιστήμιο Μακεδονίας Τμήμα Βαλκανικών, Σλαβικών και Ανατολικών Σπουδών « The evolution of the European People’s Party after the integration of parties from Western and Eastern Europe. Lessons to be learned for European Integration and the development of Europarties » Διδακτορική Διατριβή Μιχαήλ Β. Πεγκλή Επιβλέποντες καθηγητές ΝΙΚΟΛΑΟΣ ΜΑΡΑΝΤΖΙΔΗΣ ΙΩΑΝΝΗΣ ΒΑΛΗΝΑΚΗΣ ΓΕΡΑΣΣΙΜΟΣ ΜΟΣΧΟΝΑΣ ΙΟΥΝΙΟΣ 2016 1 2 Table of Contents Εισαγωγικό σημείωμα ........................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Presentation of the topic .................................................................................................................... 9 Methodology .......................................................................................................................................... 17 Chapter 1: History ................................................................................................................................... 21 The European Union of Christian Democrats ......................................................................... 35 Chapter 2: the creation of the EPP ................................................................................................... 40 The ‘linear’ approach ........................................................................................................................