KM Avhandling F Rdig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Big Is Belgium's Love Still for Europe? - the Low Countries 29/05/2020 21:18

How Big Is Belgium's Love Still for Europe? - the low countries 29/05/2020 21:18 © Trui Chielens Zero Point 1945 SOCIETY HISTORY How Big Is Belgium's Love Still for Europe? By Ellen Vanderschueren, Jasper Praet, Hendrik Vos translated by Elisabeth Salverda 29/05/2020 ! 11 min reading time After the Second World War, Belgium was one of Europe’s founders. Over the years, Belgian politicians have played a prominent role in European politics. There was always a shared feeling among the population that integration with Europe was useful and in the national interest. In recent times, however, this consensus has been somewhat worn down. n 2009, the first President of the European Council to be appointed was a I Belgian, when Herman Van Rompuy became “President of Europe”. Five years later Donald Tusk, a former prime minister of Poland, took over the helm. And five years after that, in 2019, the role fell to a Belgian once more: Charles Michel fit the jigsaw of nominations and was asked by his colleagues to chair the European Council. Belgians have quite often had a steering role in European politics. Belgium was one of the founders of the European project, and has played a very active role over the years in its process of integration. https://www.the-low-countries.com/article/how-big-is-belgiums-love-still-for-europe Pagina 1 van 15 How Big Is Belgium's Love Still for Europe? - the low countries 29/05/2020 21:18 Herman Van Rompuy and Charles Michel, the first and current President of the European Council Much has changed over the past seventy years: the Community with a focus on coal and steel has grown into a European Union that plays a significant role in almost all economic and political spheres. -

Programme of the Youth, Peace and Security Conference

1 Wednesday, 23 May European Parliament – open to all participants – 12:00 – 13:00 Registration European Parliament Accreditation Centre (right-hand side of the Simone Veil Agora entrance to the Altiero Spinelli building) 13:00 – 14:00 Buffet lunch reception Members’ Restaurant, Altiero Spinelli building 14:00 – 15:00 Opening Session Room 5G-3, Altiero Spinelli building Keynote Address by Mr. Antonio Tajani, President of the European Parliament Chair Ms. Heidi Hautala, Vice-President of the European Parliament Speakers Ms. Mariya Gabriel, EU Commissioner for Digital Economy and Society Mr. Oscar Fernandez-Taranco, UN Assistant Secretary-General for Peacebuilding Support Ms. Ivana Tufegdzic, fYROM, EP Young Political Leaders Mr. Dereje Wordofa, UNFPA Deputy Executive Director Ms. Nour Kaabi, Tunisia, NET-MED Youth – UNESCO Mr. Oyewole Simon Oginni, Nigeria, Former AU-EU Youth Fellow 2 15:00 – 16:30 Parallel Thematic Panel Discussions Panel I Youth inclusion for conflict prevention and sustaining peace Library reading room, Altiero Spinelli building Discussants Ms. Soraya Post, Member of the European Parliament Mr. Oscar Fernandez-Taranco, UN Assistant Secretary-General for Peacebuilding Support Mr. Christian Leffler, Deputy Secretary-General, European External Action Service Mr. Amnon Morag, Israel, EP Young Political Leaders Ms. Hela Slim, France, Former AU-EU Youth Fellow Mr. MacDonald K. Munyoro, Zimbabwe, EP Young Political Leaders Facilitator Ms. Gizem Kilinc, United Network of Young Peacebuilders Panel II Young people innovating for peace Library room 128, Altiero Spinelli building Discussants Ms. Barbara Pesce-Monteiro, Director, UN/UNDP Representation Office in Brussels Ms. Anna-Katharina Deininger, OSCE CiO Special Representative and OSG Focal Point on Youth and Security Ms. -

European Parliament, Daily Notebook: Motion of Censure on the Commission (11 January 1999)

European Parliament, Daily Notebook: motion of censure on the Commission (11 January 1999) Caption: The Daily Notebook details the reactions of some MEPs during a debate concerning the motion of censure on the activities of the Commission in January 1999. Source: EUROPARL - Press Service. Session News - The Daily Notebook. [ON-LINE]. [s.l.]: European Parliament, [03.08.2000]. Disponible sur http://www.europarl.eu.int/dg3/sdp/journ/en/1999/n9901112.htm#2. Copyright: (c) European Parliament URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/european_parliament_daily_notebook_motion_of_censure_on_the_commission_11_january_19 99-en-da75f293-0cc5-473e-a221-6978c1852b19.html Last updated: 28/04/2014 1 / 7 28/04/2014 European Parliament: Daily Notebook (11 January 1999) Commission faces censure (B4-1165/98, B4-0012/99, B4-0011/99, B4-0002/99, B4-0013/99, B4-0014/99, B4-0016/99, B4-0015) Monday 11 January — In tabling her motion of censure on the Commission, Pauline Green (London North, PES) declared that the decision to refuse discharge of the 1996 budget was a clear declaration that the Commission was financially incompetent. Those who voted to refuse discharge should take the only possible institutional step in their power and vote to sack the Commission. Mrs Green stated that she had tabled the censure motion so that those who felt the Commission to be culpable over the 1996 budget should face up to their responsibility and the logical consequences of their vote. She argued that the coming three months were critical for the EU and that the Commission needed to enjoy a partnership of trust and confidence with Parliament and Council. -

Unit 3 the FEDERALIST ERA

Unit 3 THE FEDERALIST ERA CHAPTER 1 THE NEW NATION ..........................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER 2 HAMILTON AND JEFFERSON— THE MEN AND THEIR PHILOSOPHIES .....................6 CHAPTER 3 PAYING THE NATIONAL DEBT ................................................................................................12 CHAPTER 4 ..............................................................................................................................................................16 HAMILTON, JEFFERSON, AND THE FIRST NATIONAL BANK OF THE UNITED STATES.............16 CHAPTER 5 THE WHISKEY REBELLION ........................................................................................................20 CHAPTER 6 NEUTRALITY AND THE JAY TREATY .....................................................................................24 CHAPTER 7 THE SEDITION ACT AND THE VIRGINIA AND KENTUCKY RESOLUTIONS ...........28 CHAPTER 8 THE ELECTION OF 1800................................................................................................................34 CHAPTER 9 JEFFERSONIANS IN OFFICE.......................................................................................................38 by Thomas Ladenburg, copyright, 1974, 1998, 2001, 2007 100 Brantwood Road, Arlington, MA 02476 781-646-4577 [email protected] Page 1 Chapter 1 The New Nation A Search for Answers hile the Founding Fathers at the Constitutional Convention debated what powers should be -

Visions of the Future: What Can Be Achieved with a Baltic Sea Strategy?

Visions of the Future: what can be achieved with a Baltic Sea Strategy? Documentation package Included is the following: • Overview programme • Seminar flyer • Presentation by Dr. Christian Ketels • Presentation by Alf Vanags • Presentation by Ulf Johansson • Contact information for participants For additional information, please contact Dr. Mikael Olsson, Sida Baltic Sea Unit, Box 1271, SE-621 23 Visby, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected]. Phone: +46-(0)732-572511 The future Baltic Sea Region Possible paths of development in the light of the emerging EU-strategy for the region Overview programme, 7-8 July, 2008 On 7-8 July, 2008, the Baltic Sea Unit constitutes one of the prioritised areas of the (Östersjöenheten) of the Swedish International Swedish presidency. Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) and Baltic Development Forum, in cooperation The meeting will focus on the parts of the with the Centre for Baltic and East European Baltic Sea Strategy that aim to deepen Studies (CBEES), Södertörn University integration and increase the global College, will arrange an international competitiveness of the region. seminar/workshop with the aim to present and discuss visions of the future of the Baltic Sea Region as well as the challenges that need to be overcome to reach the goal of a well integrated and prosperous region. The programme brings together key politicians, civil servants, practitioners and high-level academic expertise in the areas of discussion. A total of three seminars and three workshops are arranged during the two days. All events take place right in the centre of medieval Visby on the premises of the Baltic Sea Unit (Östersjöenheten) (Donners Plats 1). -

Crossing the Floor Roy Douglas a Failure of Leadership Liberal Defections 1918–29 Senator Jerry Grafstein Winston Churchill As a Liberal J

Journal of Issue 25 / Winter 1999–2000 / £5.00 Liberal DemocratHISTORY Crossing the Floor Roy Douglas A Failure of Leadership Liberal Defections 1918–29 Senator Jerry Grafstein Winston Churchill as a Liberal J. Graham Jones A Breach in the Family Megan and Gwilym Lloyd George Nick Cott The Case of the Liberal Nationals A re-evaluation Robert Maclennan MP Breaking the Mould? The SDP Liberal Democrat History Group Issue 25: Winter 1999–2000 Journal of Liberal Democrat History Political Defections Special issue: Political Defections The Journal of Liberal Democrat History is published quarterly by the Liberal Democrat History Group 3 Crossing the floor ISSN 1463-6557 Graham Lippiatt Liberal Democrat History Group Editorial The Liberal Democrat History Group promotes the discussion and research of 5 Out from under the umbrella historical topics, particularly those relating to the histories of the Liberal Democrats, Liberal Tony Little Party and the SDP. The Group organises The defection of the Liberal Unionists discussion meetings and publishes the Journal and other occasional publications. 15 Winston Churchill as a Liberal For more information, including details of publications, back issues of the Journal, tape Senator Jerry S. Grafstein records of meetings and archive and other Churchill’s career in the Liberal Party research sources, see our web site: www.dbrack.dircon.co.uk/ldhg. 18 A failure of leadership Hon President: Earl Russell. Chair: Graham Lippiatt. Roy Douglas Liberal defections 1918–29 Editorial/Correspondence Contributions to the Journal – letters, 24 Tory cuckoos in the Liberal nest? articles, and book reviews – are invited. The Journal is a refereed publication; all articles Nick Cott submitted will be reviewed. -

Chapter 6: Federalists and Republicans, 1789-1816

Federalists and Republicans 1789–1816 Why It Matters In the first government under the Constitution, important new institutions included the cabinet, a system of federal courts, and a national bank. Political parties gradually developed from the different views of citizens in the Northeast, West, and South. The new government faced special challenges in foreign affairs, including the War of 1812 with Great Britain. The Impact Today During this period, fundamental policies of American government came into being. • Politicians set important precedents for the national government and for relations between the federal and state governments. For example, the idea of a presidential cabinet originated with George Washington and has been followed by every president since that time • President Washington’s caution against foreign involvement powerfully influenced American foreign policy. The American Vision Video The Chapter 6 video, “The Battle of New Orleans,” focuses on this important event of the War of 1812. 1804 • Lewis and Clark begin to explore and map 1798 Louisiana Territory 1789 • Alien and Sedition • Washington Acts introduced 1803 elected • Louisiana Purchase doubles president ▲ 1794 size of the nation Washington • Jay’s Treaty signed J. Adams Jefferson 1789–1797 ▲ 1797–1801 ▲ 1801–1809 ▲ ▲ 1790 1797 1804 ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ 1793 1794 1805 • Louis XVI guillotined • Polish rebellion • British navy wins during French suppressed by Battle of Trafalgar Revolution Russians 1800 • Beethoven’s Symphony no. 1 written 208 Painter and President by J.L.G. Ferris 1812 • United States declares 1807 1811 war on Britain • Embargo Act blocks • Battle of Tippecanoe American trade with fought against Tecumseh 1814 Britain and France and his confederacy • Hartford Convention meets HISTORY Madison • Treaty of Ghent signed ▲ 1809–1817 ▲ ▲ ▲ Chapter Overview Visit the American Vision 1811 1818 Web site at tav.glencoe.com and click on Chapter ▼ ▼ ▼ Overviews—Chapter 6 to 1808 preview chapter information. -

The Similarities and the Differences in the Functioning of the European Right Wing: an Attempt to Integrate the European Conservatives and Christian Democrats

Journal of Social Welfare and Human Rights, Vol. 1 No. 2, December 2013 1 The Similarities and the Differences in the Functioning of the European Right Wing: An Attempt to Integrate the European Conservatives and Christian Democrats Dr. Kire Sarlamanov1 Dr. Aleksandar Jovanoski2 Abstract The text reviews the attempt of the European Conservative and Christian Democratic Parties to construct a common platform within which they could more effectively defend and develop the interests of the political right wing in the European Parliament. The text follows the chronological line of development of events, emphasizing the doctrinal and the national differences as a reason for the relative failure in the process of unification of the European right wing. The subcontext of the argumentation protrudes the ideological, the national as well as the religious-doctrinal interests of some of the more important Christian Democratic, that is, conservative parties in Europe, which emerged as an obstacle of the unification. One of the more important problems that enabled the quality and complete unification of the European conservatives and Christian Democrats is the attitude in regard to the formation of EU as a federation of countries. The weight down of the British conservatives on the side of the national sovereignty and integrity against the Pan-European idea for united European countries formed on federal basis, is considered as the most important impact on the unification of the parties from the right ideological spectrum on European land. Key words: Conservative Party, Christian Democratic Party, CDU European Union, European People’s Party. 1. Introduction On European land, the trend of connection of political parties on the basis of ideology has been notable for a long time. -

80 År För Öppenhet Och Frihet

80 år för öppenhet och frihet 80 år för öppenhet och frihet Copyright © Moderata Ungdomsförbundet Redaktör: Erik Bengtzboe Formgivning: Hellsten Kommunikation AB Illustration: Emy Eriksson / Hellsten Kommunikation AB Tryck: Livonia Print, Lettland 2014 ISBN: 978-91-637-7112-5 Förord 7 Gunnar Hökmark: Fred har den frie och ingen annan 9 Beatrice Ask: Politik som verktyg, inte som mål 21 Ulf Kristersson: Blicka framåt! 31 Fredrik Reinfeldt: Vi har valt öppenheten och friheten 39 Gunnar Strömmer: När skickade du en blomsterkvast till SSU senast? 47 Tove Lifvendahl: Frihet, kärlek och kapitalism 55 Christofer Fjellner: Politik handlar om konflikter 63 Johan Forssell: Att bygga ett nytt land 73 Niklas Wykman: Friheten behöver alla sina vänner 83 Erik Bengtzboe: Ett moderat ungdomsförbund som vill mer 95 ör 80 år sedan bildades det som i dag har blivit Sve- riges största politiska ungdomsförbund. Ända sedan 1934 har vi stått upp för frihet, för öppenhet och för individen; mot tvång, protektionism och kollektiv- Fism. Genom åren har den kampen sett olika ut, men vår tilltro till människor har alltid varit okuvad. Vi tror på människor och på framtiden, och vi är övertygade om att om människor bara får chansen, ja då kan vi också skapa stordåd. Stordåd kräver dock att kropp, plånbok, själ och hjärna är fri. I din hand håller du en samling med texter från några av oss som fått den fantastiska möjligheten att leda denna spänstiga och alltid lika pigga 80-åring genom tiderna och vara förbundsordförande för Moderata Ungdomsförbun- det. Jag är otroligt glad att så många tidigare förbundsord- föranden hade möjlighet att delta och bidra med sina per- spektiv på Moderata Ungdomsförbundet och sin tid som förbundsordförande. -

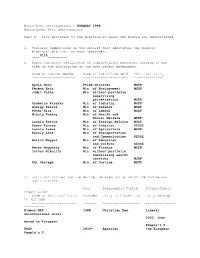

HUNGARY 1998 Macro-Level Data Questionnaire Part I: Data Pertinent

Macro-Data Questionnaire - HUNGARY 1998 Macro-Level Data Questionnaire Part I: Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1. Variable number/name in the dataset that identifies the primary electoral district for each respondent. ____V114__________ 2. Names and party affiliation of cabinet-level ministers serving at the time of the dissolution of the most recent government. Name of Cabinet Member Name of the Office Held Political Party ---------------------- ----------------------- --------------- Gyula Horn Prime Minister MSZP Ferenc Baja Min. of Environment MSZP Judit Csiha Min. without portfolio supervising privatization MSZP Szabolcs Fazakas Min. of Industry MSZP Gyorgy Keleti Min. of Defence MSZP Peter Kiss Min. of Labour MSZP Mihaly Kokeny Min. of Health and Social Welfare MSZP Laszlo Kovacs Min. of Foreign Affairs MSZP Gabor Kuncze Min. of Interior SZDSZ Laszlo Lakos Min. of Agriculture MSZP Karoly Lotz Min. of Transportation and Communication SZDSZ Balint Magyar Min. of Education and Culture SZDSZ Peter Megyessy Min. of Finance MSZP Istvan Nikolits Min. without portfolio supervising secret services MSZP Pal Vastagh Min. of Justice MSZP 3. Political Parties (active during the election at which the module was administered). Year Ideological Family International Organization Name of Political Party Founded Party is Closest to Party Belongs to (if any) ----------------------- ------- ------------------- ---------------- ---------- Fidesz-MPP 1988 Christian Dem. Liberal International until 2000, then moved to European People's P. FKGP 1930* Agrarian the European People's P. suspended the FKGP's membership in 1992 KDNP 1988 Christian Dem. The European People's P. suspended the KDNP's membership in 1997 MDF 1988 Christian Dem. European People's P. -

Ess4 - 2008 Documentation Report

ESS4 - 2008 DOCUMENTATION REPORT THE ESS DATA ARCHIVE Edition 5.5 Version Notes, ESS4 - 2008 Documentation Report ESS4 edition 5.5 (published 01.12.18): Applies to datafile ESS4 edition 4.5. Changes from edition 5.4: Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. 25 Version notes. Information updated for ESS4 ed. 4.5 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS4 ed. 4.5 data. Israel: 46 Deviations amended. Deviation in F1-F4 (HHMMB, GNDR-GNDRN, YRBRN-YRBRNN, RSHIP2-RSHIPN) added. Appendix: Appendix A3 Variables and Questions and Appendix A4 Variable lists have been replaced with Appendix A3 Codebook. ESS4 edition 5.4 (published 01.12.16): Applies to datafile ESS4 edition 4.4. Changes from edition 5.3: 25 Version notes. Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.4 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.4 data. Slovenia: 46 Deviations. Amended. Deviation in B15 (WRKORG) added. Appendix: A2 Classifications and Coding standards amended for EISCED. A3 Variables and Questions amended for EISCED, WRKORG. Documents: Education Upgrade ESS1-4 amended for EISCED. ESS4 edition 5.3 (published 26.11.14): Applies to datafile ESS4 edition 4.3 Changes from edition 5.2: All links to the ESS Website have been updated. 21 Weighting: Information regarding post-stratification weights updated. 25 Version notes: Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.3 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.3 data. Lithuania: ESS4 - 2008 Documentation Report Edition 5.5 2 46 Deviations. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zoab Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 46106 7619623

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) dr section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages, This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation.