Christian Democracy Across the Iron Curtain Piotr H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Left Info Flyer

United for a left alternative in Europe United for a left alternative in Europe ”We refer to the values and traditions of socialism, com- munism and the labor move- ment, of feminism, the fem- inist movement and gender equality, of the environmental movement and sustainable development, of peace and international solidarity, of hu- man rights, humanism and an- tifascism, of progressive and liberal thinking, both national- ly and internationally”. Manifesto of the Party of the European Left, 2004 ABOUT THE PARTY OF THE EUROPEAN LEFT (EL) EXECUTIVE BOARD The Executive Board was elected at the 4th Congress of the Party of the European Left, which took place from 13 to 15 December 2013 in Madrid. The Executive Board consists of the President and the Vice-Presidents, the Treasurer and other Members elected by the Congress, on the basis of two persons of each member party, respecting the principle of gender balance. COUNCIL OF CHAIRPERSONS The Council of Chairpersons meets at least once a year. The members are the Presidents of all the member par- ties, the President of the EL and the Vice-Presidents. The Council of Chairpersons has, with regard to the Execu- tive Board, rights of initiative and objection on important political issues. The Council of Chairpersons adopts res- olutions and recommendations which are transmitted to the Executive Board, and it also decides on applications for EL membership. NETWORKS n Balkan Network n Trade Unionists n Culture Network Network WORKING GROUPS n Central and Eastern Europe n Africa n Youth n Agriculture n Migration n Latin America n Middle East n North America n Peace n Communication n Queer n Education n Public Services n Environment n Women Trafficking Member and Observer Parties The Party of the European Left (EL) is a political party at the Eu- ropean level that was formed in 2004. -

Codebook Indiveu – Party Preferences

Codebook InDivEU – party preferences European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies December 2020 Introduction The “InDivEU – party preferences” dataset provides data on the positions of more than 400 parties from 28 countries1 on questions of (differentiated) European integration. The dataset comprises a selection of party positions taken from two existing datasets: (1) The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File contains party positions for three rounds of European Parliament elections (2009, 2014, and 2019). Party positions were determined in an iterative process of party self-placement and expert judgement. For more information: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/65944 (2) The Chapel Hill Expert Survey The Chapel Hill Expert Survey contains party positions for the national elections most closely corresponding the European Parliament elections of 2009, 2014, 2019. Party positions were determined by expert judgement. For more information: https://www.chesdata.eu/ Three additional party positions, related to DI-specific questions, are included in the dataset. These positions were determined by experts involved in the 2019 edition of euandi after the elections took place. The inclusion of party positions in the “InDivEU – party preferences” is limited to the following issues: - General questions about the EU - Questions about EU policy - Questions about differentiated integration - Questions about party ideology 1 This includes all 27 member states of the European Union in 2020, plus the United Kingdom. How to Cite When using the ‘InDivEU – Party Preferences’ dataset, please cite all of the following three articles: 1. Reiljan, Andres, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, Lorenzo Cicchi, Diego Garzia, Alexander H. -

The Similarities and the Differences in the Functioning of the European Right Wing: an Attempt to Integrate the European Conservatives and Christian Democrats

Journal of Social Welfare and Human Rights, Vol. 1 No. 2, December 2013 1 The Similarities and the Differences in the Functioning of the European Right Wing: An Attempt to Integrate the European Conservatives and Christian Democrats Dr. Kire Sarlamanov1 Dr. Aleksandar Jovanoski2 Abstract The text reviews the attempt of the European Conservative and Christian Democratic Parties to construct a common platform within which they could more effectively defend and develop the interests of the political right wing in the European Parliament. The text follows the chronological line of development of events, emphasizing the doctrinal and the national differences as a reason for the relative failure in the process of unification of the European right wing. The subcontext of the argumentation protrudes the ideological, the national as well as the religious-doctrinal interests of some of the more important Christian Democratic, that is, conservative parties in Europe, which emerged as an obstacle of the unification. One of the more important problems that enabled the quality and complete unification of the European conservatives and Christian Democrats is the attitude in regard to the formation of EU as a federation of countries. The weight down of the British conservatives on the side of the national sovereignty and integrity against the Pan-European idea for united European countries formed on federal basis, is considered as the most important impact on the unification of the parties from the right ideological spectrum on European land. Key words: Conservative Party, Christian Democratic Party, CDU European Union, European People’s Party. 1. Introduction On European land, the trend of connection of political parties on the basis of ideology has been notable for a long time. -

Are Gestures Worth a Thousand Words? an Analysis of Interviews in the Political Domain

Are Gestures Worth a Thousand Words? An Analysis of Interviews in the Political Domain Daniela Trotta Sara Tonelli Universita` degli Studi di Salerno Fondazione Bruno Kessler Via Giovanni Paolo II 132, Via Sommarive 18 Fisciano, Italy Trento, Italy [email protected] [email protected] Abstract may provide important information or significance to the accompanying speech and add clarity to the Speaker gestures are semantically co- expressive with speech and serve different children’s narrative (Colletta et al., 2015); they can pragmatic functions to accompany oral modal- be employed to facilitate lexical retrieval and re- ity. Therefore, gestures are an inseparable tain a turn in conversations stam2008gesture and part of the language system: they may add assist in verbalizing semantic content (Hostetter clarity to discourse, can be employed to et al., 2007). From this point of view, gestures fa- facilitate lexical retrieval and retain a turn in cilitate speakers in coming up with the words they conversations, assist in verbalizing semantic intend to say by sustaining the activation of a tar- content and facilitate speakers in coming up with the words they intend to say. This aspect get word’s semantic feature, long enough for the is particularly relevant in political discourse, process of word production to take place (Morsella where speakers try to apply communication and Krauss, 2004). strategies that are both clear and persuasive Gestures can also convey semantic meanings. using verbal and non-verbal cues. For example,M uller¨ et al.(2013) discuss the prin- In this paper we investigate the co-speech ges- ciples of meaning creation and the simultaneous tures of several Italian politicians during face- and linear structures of gesture forms. -

Politica E Istituzioni Negli Scritti Di Antonio Segni

Politica e istituzioni negli scritti di Antonio Segni Questa antologia di scritti politici vuol essere un con- tributo alla ricostruzione della biografia intellettuale e politica di Antonio Segni. L’interpretazione sull’opera di Segni ancora oggi prevalente – anche se, in seguito a recenti studi, comincia a mostrare le sue debolezze – è condizionata dalla decennale polemica politica sui fatti dell’estate del 19641. Si tratta di un’interpretazio- 1 Tra gli studi più recenti dedicati a Segni mi permetto di rinviare a S. Mura, Le esperienze istituzionali di Antonio Segni negli anni del Diario, in A. Segni, Diario (1956-1964), a cura di S. Mura, Bologna, il Mulino, 2012, pp. 21-97. Per un completo profilo biografico, A. Giovagnoli, Antonio Segni, in Il Parlamento Italiano. 1861-1988. Il centro-sinistra. La “stagione” di Moro e Nenni. 1964-1968, vol. XIX, Milano, Nuova Cei, 1992, pp. 244-268. Su Segni professore universitario e giurista, soprattutto: A. Mattone, Segni Antonio, in Dizionario biografico dei giuristi italiani (XII-XX secolo), diretto da I. Birocchi, E. Cortese, A. Mattone, M. N. Miletti, a cura di M. L. Carlino, G. De Giudici, E. Fab- bricatore, E. Mura, M. Sammarco, vol. II, Bologna, il Mulino, 2013, pp. 1843-1845; G. Fois, Storia dell’Università di Sassari 1859-1943, Roma, Carocci, 2000; A. Mattone, Gli studi giuridici e l’insegnamento del diritto (XVII-XX secolo), in Idem (a cura di), Storia dell’Università di Sassari, vol. I, Nuoro, Ilisso, 2010, pp. 221-230; F. Cipriani, Storie di processualisti e di oligarchi. La procedura civile nel Regno d’Italia (1866-1936), Milano, Giuffrè, 1991. -

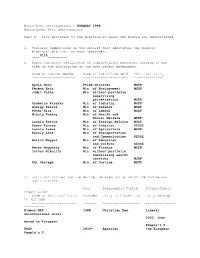

HUNGARY 1998 Macro-Level Data Questionnaire Part I: Data Pertinent

Macro-Data Questionnaire - HUNGARY 1998 Macro-Level Data Questionnaire Part I: Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1. Variable number/name in the dataset that identifies the primary electoral district for each respondent. ____V114__________ 2. Names and party affiliation of cabinet-level ministers serving at the time of the dissolution of the most recent government. Name of Cabinet Member Name of the Office Held Political Party ---------------------- ----------------------- --------------- Gyula Horn Prime Minister MSZP Ferenc Baja Min. of Environment MSZP Judit Csiha Min. without portfolio supervising privatization MSZP Szabolcs Fazakas Min. of Industry MSZP Gyorgy Keleti Min. of Defence MSZP Peter Kiss Min. of Labour MSZP Mihaly Kokeny Min. of Health and Social Welfare MSZP Laszlo Kovacs Min. of Foreign Affairs MSZP Gabor Kuncze Min. of Interior SZDSZ Laszlo Lakos Min. of Agriculture MSZP Karoly Lotz Min. of Transportation and Communication SZDSZ Balint Magyar Min. of Education and Culture SZDSZ Peter Megyessy Min. of Finance MSZP Istvan Nikolits Min. without portfolio supervising secret services MSZP Pal Vastagh Min. of Justice MSZP 3. Political Parties (active during the election at which the module was administered). Year Ideological Family International Organization Name of Political Party Founded Party is Closest to Party Belongs to (if any) ----------------------- ------- ------------------- ---------------- ---------- Fidesz-MPP 1988 Christian Dem. Liberal International until 2000, then moved to European People's P. FKGP 1930* Agrarian the European People's P. suspended the FKGP's membership in 1992 KDNP 1988 Christian Dem. The European People's P. suspended the KDNP's membership in 1997 MDF 1988 Christian Dem. European People's P. -

Ess4 - 2008 Documentation Report

ESS4 - 2008 DOCUMENTATION REPORT THE ESS DATA ARCHIVE Edition 5.5 Version Notes, ESS4 - 2008 Documentation Report ESS4 edition 5.5 (published 01.12.18): Applies to datafile ESS4 edition 4.5. Changes from edition 5.4: Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. 25 Version notes. Information updated for ESS4 ed. 4.5 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS4 ed. 4.5 data. Israel: 46 Deviations amended. Deviation in F1-F4 (HHMMB, GNDR-GNDRN, YRBRN-YRBRNN, RSHIP2-RSHIPN) added. Appendix: Appendix A3 Variables and Questions and Appendix A4 Variable lists have been replaced with Appendix A3 Codebook. ESS4 edition 5.4 (published 01.12.16): Applies to datafile ESS4 edition 4.4. Changes from edition 5.3: 25 Version notes. Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.4 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.4 data. Slovenia: 46 Deviations. Amended. Deviation in B15 (WRKORG) added. Appendix: A2 Classifications and Coding standards amended for EISCED. A3 Variables and Questions amended for EISCED, WRKORG. Documents: Education Upgrade ESS1-4 amended for EISCED. ESS4 edition 5.3 (published 26.11.14): Applies to datafile ESS4 edition 4.3 Changes from edition 5.2: All links to the ESS Website have been updated. 21 Weighting: Information regarding post-stratification weights updated. 25 Version notes: Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.3 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.3 data. Lithuania: ESS4 - 2008 Documentation Report Edition 5.5 2 46 Deviations. -

Elenco Dei Governi Italiani

Elenco dei Governi Italiani Questo è un elenco dei Governi Italiani e dei relativi Presidenti del Consiglio dei Ministri. Le Istituzioni in Italia Le istituzioni della Repubblica Italiana Costituzione Parlamento o Camera dei deputati o Senato della Repubblica o Legislature Presidente della Repubblica Governo (categoria) o Consiglio dei Ministri o Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri o Governi Magistratura Consiglio Superiore della Magistratura (CSM) Consiglio di Stato Corte dei Conti Governo locale (Suddivisioni) o Regioni o Province o Comuni Corte costituzionale Unione Europea Relazioni internazionali Partiti e politici Leggi e Regolamenti parlamentari Elezioni e Calendario Referendum modifica Categorie: Politica, Diritto e Stato Portale Italia Portale Politica Indice [nascondi] 1 Regno d'Italia 2 Repubblica Italiana 3 Sigle e abbreviazioni 4 Politici con maggior numero di Governi della Repubblica Italiana 5 Voci correlate Regno d'Italia Periodo Nome del Governo Primo Ministro 23 marzo 1861 - 12 giugno 1861 Governo Cavour Camillo Benso Conte di Cavour[1] 12 giugno 1861 - 3 marzo 1862 Governo Ricasoli I Bettino Ricasoli 3 marzo 1862 - 8 dicembre 1862 Governo Rattazzi I Urbano Rattazzi 8 dicembre 1862 - 24 marzo 1863 Governo Farini Luigi Carlo Farini 24 marzo 1863 - 28 settembre 1864 Governo Minghetti I Marco Minghetti 28 settembre 1864 - 31 dicembre Governo La Marmora Alfonso La Marmora 1865 I Governo La Marmora 31 dicembre 1865 - 20 giugno 1866 Alfonso La Marmora II 20 giugno 1866 - 10 aprile 1867 Governo Ricasoli -

The Holy See

The Holy See ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI TO MEMBERS OF THE COUNCIL OF THE "ALCIDE DE GASPERI" FOUNDATION Hall of Popes Saturday, 20 June 2009 Dear Friends of the Council of the Alcide De Gasperi Foundation, I deeply appreciate your visit and greet you all with affection. In particular, I greet Mrs Maria Romana, daughter of Alcide De Gasperi, and Hon. Giulio Andreotti who was his close collaborator for many years. I willingly take the opportunity that your presence affords me to recall this great figure who, in historical periods of profound social change in Italy and in Europe, beset with problems, was able to work effectively for the common good. Formed at the school of the Gospel, De Gasperi was able to express the faith he professed in consistent, concrete actions. Indeed, spirituality and politics were two dimensions that co-existed within him and characterized his social and spiritual commitment. He guided the reconstruction of Italy that was emerging from Fascism and from the Second World War with prudent foresight and courageously plotted the path to the future; he defended freedom and democracy in the country. He relaunched Italy's image on the international scene and promoted economic recovery, opening himself to collaboration with all people of good will. Spirituality and politics were so well integrated in him that if one wishes to understand this esteemed government leader properly one should not limit oneself to taking stock of the political results he achieved, but rather must also note his fine religious sensibility and firm faith which never ceased to motivate his thought and action. -

Portale Storico Della Presidenza Della

PRESIDENZA DELLA REPUBBLICA DIARIO STORICO - Cerimoniale - Intervento del Presidente della Repubblica a Trento in occasione del conferimento del Premio “Alcide De Gasperi: Costruttori d’Europa” al Senatore di diritto a vita - Presidente Emerito della Repubblica, Dott. Carlo Azeglio Ciampi. TRENTO – Sabato 19 agosto 2006 --------------- 11.30 L’aereo presidenziale, proveniente da Lucerna, atterra all’Aeroporto di Bolzano. Discesi dal velivolo, il Presidente della Repubblica e la Signora Napolitano sono accolti, in forma strettamente privata, dal Commissario del Governo per la provincia di Bolzano, Dott. Giuseppe Destro, e dal Direttore dell’Aeroporto, Dott. Manfred Mussner. Sono altresì presenti i Consiglieri per gli Affari Interni e per la Stampa e l’Informazione del Presidente della Repubblica. Il Capo dello Stato e la Signora Napolitano prendono quindi posto in auto per raggiungere una struttura di rappresentanza nel complesso aeroportuale. (Corteo: allegato A) Quivi giunto, il Presidente della Repubblica, dopo aver ricevuto il saluto del Sindaco, Dott. Luigi Spagnoli, incontra il Presidente della Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano, Dott. Luis Durnwalder. Nel contempo, la Signora Napolitano, unitamente alle altre Signore presenti, si intrattiene in un salotto di rappresentanza. 12.10 Il Presidente della Repubblica e la Signora Napolitano, preso congedo dalle Personalità che erano ad accogliere all’arrivo, lasciano in auto Bolzano per recarsi a Trento. 13.00 Il corteo presidenziale giunge al Grand Hotel di Trento, ove il Presidente della Repubblica e la Signora Napolitano sono accolti dal Direttore dell’albergo. E’ altresì presente il Segretario Generale Onorario della Presidenza della Repubblica, con la Consorte. 13.15 Colazione in forma privata. (Partecipanti alla colazione: allegato B) Pausa. -

Draft Report 08-12-2010 FINALMA

Training Course for Youth Leaders of the African Diaspora Living in Europe Tarrafal, Cape Verde 4 – 12 July 2010 Report - August 2010 - 1 Training Course for Youth Leaders of the African Diaspora Living in Europe Tarrafal, Cape Verde 4 – 12 July 2010 INDEX 1. Course Introduction 1.1 Background of TC ..........................................................................................................3 1.2 Aims and Objectives......................................................................................................4 1.3 Methodological Approach and Pedagogical Team ........................................................4 1.4 Expected Results and Profile of Participants.................................................................5 2. Programme Elements 2.1 Programme....................................................................................................................6 2.2 Training Session Outlines ..............................................................................................8 2.3 Session Outcomes .........................................................................................................9 3. Evaluation 3.1 Participants Evaluation (results of evaluation forms) ...................................................27 3.2 Team Evaluation ............................................................................................................32 4. Annexes 4.1 Reflection Groups Guide ...............................................................................................33 4.2 -

The 18 April 1948 Italian Election: Seventy Years on Page 1 of 4

LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) Blog: The 18 April 1948 Italian election: Seventy years on Page 1 of 4 The 18 April 1948 Italian election: Seventy years on Italy’s election on 4 March was far from the first Italian election campaign to have generated high levels of interest across the rest of Europe. Effie G. H. Pedaliu writes on the seventieth anniversary of one of Italy’s most significant and controversial elections: the 1948 Italian general election, which pitted the country’s Christian Democrats against the Popular Democratic Front in which the Italian Communist Party, the largest communist party outside the Soviet Union, was the dominant partner. The sound and fury unleashed by the populist onslaught in Italy’s recent general election on 4 March 2018 may obscure the seventieth anniversary of one of the country’s most significant, controversial and decisive general elections, that of 18 April 1948. The 1948 election was the first general election since Mussolini’s ‘march on Rome’ in 1922 and Italians were going to the ballot box not just to elect a government, but also to determine the political orientation of their country. The result would not only shape the future of Italy, but it was also considered to be critical to the survival of the West and the post WWII liberal democratic order. Italians faced a straight choice: to vote either for Alcide de Gasperi’s Christian Democrats or Palmiro Toglatti’s and Pietro Nenni’s Popular Democratic Front in which the Italian Communist Party, the largest communist party outside the Soviet Union, was the dominant partner.