European Union Foreign Affairs Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whither Communism: a Comparative Perspective on Constitutionalism in a Postsocialist Cuba Jon L

University of Florida Levin College of Law UF Law Scholarship Repository UF Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2009 Whither Communism: A Comparative Perspective on Constitutionalism in a Postsocialist Cuba Jon L. Mills University of Florida Levin College of Law, [email protected] Daniel Ryan Koslosky Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Jon Mills & Daniel Ryan Koslosky, Whither Communism: A Comparative Perspective on Constitutionalism in a Postsocialist Cuba, 40 Geo. Wash. Int'l L. Rev. 1219 (2009), available at, http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/522 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UF Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHITHER COMMUNISM: A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE ON CONSTITUTIONALISM IN A POSTSOCIALIST CUBA JON MILLS* AND DANIEL RYAN KOSLOSIc4 I. INTRODUCTION ........................................ 1220 II. HISTORY AND BACKGROUND ............................ 1222 A. Cuban ConstitutionalLaw .......................... 1223 1. Precommunist Legacy ........................ 1223 2. Communist Constitutionalism ................ 1225 B. Comparisons with Eastern Europe ................... 1229 1. Nationalizations in Eastern Europe ........... 1230 2. Cuban Expropriations ........................ 1231 III. MODES OF CONSTITUTIONALISM: A SCENARIO ANALYSIS. 1234 A. Latvia and the Problem of ConstitutionalInheritance . 1236 1. History, Revolution, and Reform ............. 1236 2. Resurrecting an Ancien Rgime ................ 1239 B. Czechoslovakia and Poland: Revolutions from Below .. 1241 1. Poland's Solidarity ........................... 1241 2. Czechoslovakia's Velvet Revolution ........... 1244 3. New Constitutionalism ....................... 1248 C. Hungary's GradualDecline and Decay .............. -

Lithuanian Jews and the Holocaust

Ezra’s Archives | 77 Strategies of Survival: Lithuanian Jews and the Holocaust Taly Matiteyahu On the eve of World War II, Lithuanian Jewry numbered approximately 220,000. In June 1941, the war between Germany and the Soviet Union began. Within days, Germany had occupied the entirety of Lithuania. By the end of 1941, only about 43,500 Lithuanian Jews (19.7 percent of the prewar population) remained alive, the majority of whom were kept in four ghettos (Vilnius, Kaunas, Siauliai, Svencionys). Of these 43,500 Jews, approximately 13,000 survived the war. Ultimately, it is estimated that 94 percent of Lithuanian Jewry died during the Holocaust, a percentage higher than in any other occupied Eastern European country.1 Stories of Lithuanian towns and the manner in which Lithuanian Jews responded to the genocide have been overlooked as the perpetrator- focused version of history examines only the consequences of the Holocaust. Through a study utilizing both historical analysis and testimonial information, I seek to reconstruct the histories of Lithuanian Jewish communities of smaller towns to further understand the survival strategies of their inhabitants. I examined a variety of sources, ranging from scholarly studies to government-issued pamphlets, written testimonies and video testimonials. My project centers on a collection of 1 Population estimates for Lithuanian Jews range from 200,000 to 250,000, percentages of those killed during Nazi occupation range from 90 percent to 95 percent, and approximations of the number of survivors range from 8,000 to 20,000. Here I use estimates provided by Dov Levin, a prominent international scholar of Eastern European Jewish history, in the Introduction to Preserving Our Litvak Heritage: A History of 31 Jewish Communities in Lithuania. -

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter Utgivna Av Statsvetenskapliga Föreningen I Uppsala 194

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter utgivna av Statsvetenskapliga föreningen i Uppsala 194 Jessica Giandomenico Transformative Power Challenged EU Membership Conditionality in the Western Balkans Revisited Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Brusewitzsalen, Gamla Torget 6, Uppsala, Saturday, 19 December 2015 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Professor David Phinnemore. Abstract Giandomenico, J. 2015. Transformative Power Challenged. EU Membership Conditionality in the Western Balkans Revisited. Skrifter utgivna av Statsvetenskapliga föreningen i Uppsala 194. 237 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-554-9403-2. The EU is assumed to have a strong top-down transformative power over the states applying for membership. But despite intensive research on the EU membership conditionality, the transformative power of the EU in itself has been left curiously understudied. This thesis seeks to change that, and suggests a model based on relational power to analyse and understand how the transformative power is seemingly weaker in the Western Balkans than in Central and Eastern Europe. This thesis shows that the transformative power of the EU is not static but changes over time, based on the relationship between the EU and the applicant states, rather than on power resources. This relationship is affected by a number of factors derived from both the EU itself and on factors in the applicant states. As the relationship changes over time, countries and even issues, the transformative power changes with it. The EU is caught in a path dependent like pattern, defined by both previous commitments and the built up foreign policy role as a normative power, and on the nature of the decision making procedures. -

Conde, Jonathan (2018) an Examination of Lithuania's Partisan War Versus the Soviet Union and Attempts to Resist Sovietisation

Conde, Jonathan (2018) An Examination of Lithuania’s Partisan War Versus the Soviet Union and Attempts to Resist Sovietisation. Masters thesis, York St John University. Downloaded from: http://ray.yorksj.ac.uk/id/eprint/3522/ Research at York St John (RaY) is an institutional repository. It supports the principles of open access by making the research outputs of the University available in digital form. Copyright of the items stored in RaY reside with the authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full text items free of charge, and may download a copy for private study or non-commercial research. For further reuse terms, see licence terms governing individual outputs. Institutional Repository Policy Statement RaY Research at the University of York St John For more information please contact RaY at [email protected] An Examination of Lithuania’s Partisan War Versus the Soviet Union and Attempts to Resist Sovietisation. Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Research MA History at York St John University School of Humanities, Religion & Philosophy by Jonathan William Conde Student Number: 090002177 April 2018 I confirm that the work submitted is my own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the works of others. This copy has been submitted on the understanding that it is copyright material. Any reuse must comply with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and any licence under which this copy is released. @2018 York St John University and Jonathan William Conde The right of Jonathan William Conde to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 Acknowledgments My gratitude for assisting with this project must go to my wife, her parents, wider family, and friends in Lithuania, and all the people of interest who I interviewed between the autumn of 2014 and winter 2017. -

Fighters-For-Freedom.Pdf

FIGHTERS FOR FREEDOM Lithuanian Partisans Versus the U.S.S.R. by Juozas Daumantas This is a factual, first-hand account of the activities of the armed resistance movement in Lithuania during the first three years of Russian occupation (1944-47) and of the desperate conditions which brought it about. The author, a leading figure in the movement, vividly describes how he and countless other young Lithuanian men and women were forced by relentless Soviet persecutions to abandon their everyday activities and take up arms against their nation’s oppressors. Living as virtual outlaws, hiding in forests, knowing that at any moment they might be hunted down and killed like so many wild animals, these young freedom fighters were nonetheless determined to strike back with every resource at their command. We see them risking their lives to protect Lithuanian farmers against Red Army marauders, publishing underground news papers to combat the vast Communist propaganda machine, even pitting their meager forces against the dreaded NKVD and MGB. JUOZAS DAUMANTAS FIGHTERS FOR FREEDOM LITHUANIAN PARTISANS VERSUS THE U.S.S.R. (1944-1947) Translated from the Lithuanian by E. J. Harrison and Manyland Books SECOND EDITION FIGHTERS FOR FREEDOM Copyright © 1975 by Nijole Brazenas-Paronetto Published by The Lithuanian Canadian Committee for Human Rights, 1988 1011 College Street, Toronto, Ontario, M6H 1A8 Library of Congress Catalog Card No.: 74-33547 ISBN 0-87141-049-4 CONTENTS Page Prelude: July, 1944 5 Another “Liberation” 10 The Story of the Red Army Soldier, -

The Similarities and the Differences in the Functioning of the European Right Wing: an Attempt to Integrate the European Conservatives and Christian Democrats

Journal of Social Welfare and Human Rights, Vol. 1 No. 2, December 2013 1 The Similarities and the Differences in the Functioning of the European Right Wing: An Attempt to Integrate the European Conservatives and Christian Democrats Dr. Kire Sarlamanov1 Dr. Aleksandar Jovanoski2 Abstract The text reviews the attempt of the European Conservative and Christian Democratic Parties to construct a common platform within which they could more effectively defend and develop the interests of the political right wing in the European Parliament. The text follows the chronological line of development of events, emphasizing the doctrinal and the national differences as a reason for the relative failure in the process of unification of the European right wing. The subcontext of the argumentation protrudes the ideological, the national as well as the religious-doctrinal interests of some of the more important Christian Democratic, that is, conservative parties in Europe, which emerged as an obstacle of the unification. One of the more important problems that enabled the quality and complete unification of the European conservatives and Christian Democrats is the attitude in regard to the formation of EU as a federation of countries. The weight down of the British conservatives on the side of the national sovereignty and integrity against the Pan-European idea for united European countries formed on federal basis, is considered as the most important impact on the unification of the parties from the right ideological spectrum on European land. Key words: Conservative Party, Christian Democratic Party, CDU European Union, European People’s Party. 1. Introduction On European land, the trend of connection of political parties on the basis of ideology has been notable for a long time. -

Blood Ties: Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878

BLOOD TIES BLOOD TIES Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 I˙pek Yosmaog˘lu Cornell University Press Ithaca & London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 2014 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yosmaog˘lu, I˙pek, author. Blood ties : religion, violence,. and the politics of nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 / Ipek K. Yosmaog˘lu. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5226-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8014-7924-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Macedonia—History—1878–1912. 2. Nationalism—Macedonia—History. 3. Macedonian question. 4. Macedonia—Ethnic relations. 5. Ethnic conflict— Macedonia—History. 6. Political violence—Macedonia—History. I. Title. DR2215.Y67 2013 949.76′01—dc23 2013021661 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paperback printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Josh Contents Acknowledgments ix Note on Transliteration xiii Introduction 1 1. -

1Daskalov R Tchavdar M Ed En

Entangled Histories of the Balkans Balkan Studies Library Editor-in-Chief Zoran Milutinović, University College London Editorial Board Gordon N. Bardos, Columbia University Alex Drace-Francis, University of Amsterdam Jasna Dragović-Soso, Goldsmiths, University of London Christian Voss, Humboldt University, Berlin Advisory Board Marie-Janine Calic, University of Munich Lenard J. Cohen, Simon Fraser University Radmila Gorup, Columbia University Robert M. Hayden, University of Pittsburgh Robert Hodel, Hamburg University Anna Krasteva, New Bulgarian University Galin Tihanov, Queen Mary, University of London Maria Todorova, University of Illinois Andrew Wachtel, Northwestern University VOLUME 9 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bsl Entangled Histories of the Balkans Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies Edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover Illustration: Top left: Krste Misirkov (1874–1926), philologist and publicist, founder of Macedo- nian national ideology and the Macedonian standard language. Photographer unknown. Top right: Rigas Feraios (1757–1798), Greek political thinker and revolutionary, ideologist of the Greek Enlightenment. Portrait by Andreas Kriezis (1816–1880), Benaki Museum, Athens. Bottom left: Vuk Karadžić (1787–1864), philologist, ethnographer and linguist, reformer of the Serbian language and founder of Serbo-Croatian. 1865, lithography by Josef Kriehuber. Bottom right: Şemseddin Sami Frashëri (1850–1904), Albanian writer and scholar, ideologist of Albanian and of modern Turkish nationalism, with his wife Emine. Photo around 1900, photo- grapher unknown. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Entangled histories of the Balkans / edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov. pages cm — (Balkan studies library ; Volume 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

The Macedonia-Greece Dispute/Difference Over the Name Issue: Mitigating the Inherently Unsolvable

New Balkan Politics Issue 14, 2013 The Macedonia-Greece dispute/difference over the name issue: mitigating the inherently unsolvable Hristijan Ivanovski1 Center for Defence and Security Studies University of Manitoba [email protected] Abstract Having entered its third decade, the Macedonia-Greece naming disputei seems as if it is set to join an infamous category of international relations—that of the world‘s chronic unsolvable issues. By focusing on the post-2006 decline in Macedonian-Greek (political) relations and the stalemate in negotiations on the name issue, this paper lays out and reassesses most of the fundamental components and recent variables in the dispute but also seeks to demystify important aspects of the dispute and to identify the space for a rational, common sense solution. Beginning with a substantiated claim that obstructive politics have been practised by certain NATO/EU circles towards Macedonia, and going on to deconstruct the myth that the dispute is purely bilateral and limited only to the name issue, this article warns that the intermittent optimism exhibited among the stakeholders in the negotiations means little given the historical depth of this otherwise simple dispute. The main message of this paper, however, is contained in a subsequent definition of the dispute as (part of) a perverse, inherently unsolvable, centuries-old problem that can only be mitigated rather than conclusively addressed, since it is based on vital, incompatible national interests and, consequently, a rigid, inter-state/inter- society disagreement. The pressing need to mitigate the dispute via local pragmatism, balanced diplomatic pressure, and the adoption of an inventive approach, especially after the Kosovo problem has been satisfactorily closed (at least temporarily), guarantees almost nothing, since both Macedonia and Greece have strong strategic rationales for not approaching a compromise. -

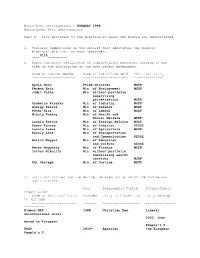

HUNGARY 1998 Macro-Level Data Questionnaire Part I: Data Pertinent

Macro-Data Questionnaire - HUNGARY 1998 Macro-Level Data Questionnaire Part I: Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1. Variable number/name in the dataset that identifies the primary electoral district for each respondent. ____V114__________ 2. Names and party affiliation of cabinet-level ministers serving at the time of the dissolution of the most recent government. Name of Cabinet Member Name of the Office Held Political Party ---------------------- ----------------------- --------------- Gyula Horn Prime Minister MSZP Ferenc Baja Min. of Environment MSZP Judit Csiha Min. without portfolio supervising privatization MSZP Szabolcs Fazakas Min. of Industry MSZP Gyorgy Keleti Min. of Defence MSZP Peter Kiss Min. of Labour MSZP Mihaly Kokeny Min. of Health and Social Welfare MSZP Laszlo Kovacs Min. of Foreign Affairs MSZP Gabor Kuncze Min. of Interior SZDSZ Laszlo Lakos Min. of Agriculture MSZP Karoly Lotz Min. of Transportation and Communication SZDSZ Balint Magyar Min. of Education and Culture SZDSZ Peter Megyessy Min. of Finance MSZP Istvan Nikolits Min. without portfolio supervising secret services MSZP Pal Vastagh Min. of Justice MSZP 3. Political Parties (active during the election at which the module was administered). Year Ideological Family International Organization Name of Political Party Founded Party is Closest to Party Belongs to (if any) ----------------------- ------- ------------------- ---------------- ---------- Fidesz-MPP 1988 Christian Dem. Liberal International until 2000, then moved to European People's P. FKGP 1930* Agrarian the European People's P. suspended the FKGP's membership in 1992 KDNP 1988 Christian Dem. The European People's P. suspended the KDNP's membership in 1997 MDF 1988 Christian Dem. European People's P. -

Ess4 - 2008 Documentation Report

ESS4 - 2008 DOCUMENTATION REPORT THE ESS DATA ARCHIVE Edition 5.5 Version Notes, ESS4 - 2008 Documentation Report ESS4 edition 5.5 (published 01.12.18): Applies to datafile ESS4 edition 4.5. Changes from edition 5.4: Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. 25 Version notes. Information updated for ESS4 ed. 4.5 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS4 ed. 4.5 data. Israel: 46 Deviations amended. Deviation in F1-F4 (HHMMB, GNDR-GNDRN, YRBRN-YRBRNN, RSHIP2-RSHIPN) added. Appendix: Appendix A3 Variables and Questions and Appendix A4 Variable lists have been replaced with Appendix A3 Codebook. ESS4 edition 5.4 (published 01.12.16): Applies to datafile ESS4 edition 4.4. Changes from edition 5.3: 25 Version notes. Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.4 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.4 data. Slovenia: 46 Deviations. Amended. Deviation in B15 (WRKORG) added. Appendix: A2 Classifications and Coding standards amended for EISCED. A3 Variables and Questions amended for EISCED, WRKORG. Documents: Education Upgrade ESS1-4 amended for EISCED. ESS4 edition 5.3 (published 26.11.14): Applies to datafile ESS4 edition 4.3 Changes from edition 5.2: All links to the ESS Website have been updated. 21 Weighting: Information regarding post-stratification weights updated. 25 Version notes: Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.3 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.3 data. Lithuania: ESS4 - 2008 Documentation Report Edition 5.5 2 46 Deviations. -

2014-2024 Management Plan Prespa National Park in Albania

2014-2024 Management Plan Prespa National Park in Albania MANAGEMENT PLAN of the PRESPA NATIONAL PARK IN ALBANIA 2014-2024 1 2014-2024 Management Plan Prespa National Park in Albania ABBREVIATIONS ALL Albanian Lek a.s.l. Above Sea Level BCA Biodiversity Conservation Advisor BMZ Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, Germany CDM Clean Development Mechanism Corg Organic Carbon DCM Decision of Council of Ministers DFS Directorate for Forestry Service, Korca DGFP Directorate General for Forestry and Pastures DTL Deputy Team Leader EUNIS European Union Nature Information System GEF Global Environment Facility GFA GFA Consulting Group, Germany GNP Galicica National Park GO Governmental Organisation GTZ/GIZ German Agency for Technical Cooperation, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (Name changed to GIZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit) FAO Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature The World Conservation Union FUA Forest User Association Prespa KfW Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau - Entwicklungsbank/German Development Bank LMS Long Term Monitoring Sites LSU Livestock Unit MC Management Committee of the Prespa National Parkin Albania METT Management Effectiveness Tracking Tool MoE Ministry of Environment of Albania MP Management Plan NGO Non-Governmental Organisation NP National Park NPA National Park Administration NPD National Park Director (currently Chief of Sector of Directorate for Forestry Service, Korca) PNP National