Crucifixion in the Ancient World and the Folly of the Message of the Cross, Trans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

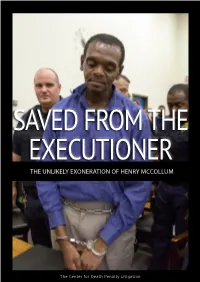

SAVED from the EXECUTIONER: the Unlikely Exoneration of Henry

SAVED FROM THE EXECUTIONER THE UNLIKELY EXONERATION OF HENRY MCCOLLUM The Center for Death Penalty Litigation HENRY MCCOLLUM f all the men and women on death row in North Carolina, Henry McCollum’s guilty verdict looked O airtight. He had signed a confession full of grisly details. Written in crude and unapologetic language, it told the story of four boys, he among them, raping 11-year-old Sabrina Buie, and suffocating her by shoving her own underwear down her throat. He had confessed again in front of television cameras shortly after. His younger brother, Leon Brown, also admitted involvement in the crime. Both were sen- tenced to death in 1984. Leon was later resentenced to life in prison. But Henry remained on death row for 30 years and became Exhibit A in the defense of the death penalty. U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia pointed to the brutality of Henry’s crime as a reason to continue capital punishment nation- wide. During North Carolina legislative elections in 2010, Henry’s face showed up on political flyers, the example of a brutal rapist and child killer who deserved to be executed. What almost no one saw — not even his top-notch defense attorneys — was that Henry McCollum was inno- cent. He had nothing to do with Sabrina’s murder. Nor did Leon. In 2014, both were exonerated by DNA evidence and, in 2015, then-Gov. Pat McCrory granted them a rare LEON BROWN pardon of innocence. Though Henry insisted on his innocence for decades, the truth was painfully slow to emerge: Two intellectually disabled teenagers – naive, powerless, and intimidated by a cadre of law enforcement officers – had been pres- sured into signing false confessions. -

Prison Guards and the Death Penalty

BRIEFING PAPER Prison guards and the death penalty Introduction and elsewhere.3 In Japan, in the latter stages before execution, all communication between prisoners or When we think about the people affected by the death between guards and prisoners is forbidden.4 penalty, we may not think about guards on death rows. But these officials, whether they oversee prisoners In 2014, the Texas prison guards union appealed for awaiting execution or participate in the execution itself, better death row prisoner conditions, because the can be deeply affected by their role in helping to put a guards faced daily danger from prisoners made mentally person to death. ill by solitary confinement and who had ‘nothing to lose’.5 In this environment, routine safety practices were imposed that dehumanised prisoners and guards alike, Guards on death row such as every exit of a cell requiring a strip search. Persons sentenced to death are usually considered Guards protested that their own dignity was undermined among the most dangerous prisoners and are placed by the obligation to look at ‘one naked inmate after in the highest security conditions. Prison guards are another’6 all day. frequently suspicious of death row prisoners, are particularly vigilant around them,1 and experience death row as a dangerous place. Interactions with prisoners Despite the stark conditions, death rows are still places Harsh prison conditions can make things worse not where human connections form. In all but the most only for prisoners but also for guards. The mental extreme solitary settings, guards engage with prisoners health of death row prisoners frequently deteriorates regularly, bringing them food and accompanying them and they may suffer from ‘death row phenomenon’, the when they leave their cells (for example to exercise, ‘condition of mental and emotional distress brought on receive visits or attend court hearings). -

July 31, 2020 Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz Via Electronic Delivery

July 31, 2020 Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz Via electronic delivery Dear Chancellor Guskiewicz: On behalf of the Commission on History, Race, and a Way Forward, we write to follow up on the Board of Trustees’ July 29 meeting, specifically with regard to the interim decision to leave the name of Thomas Ruffin Jr. on Ruffin Residence Hall. New evidence has come to light, which does not appear in any published account of Klan violence during the Reconstruction era. It is in the form of newspaper stories and public correspondence that link Ruffin to a legislative grant of amnesty to Klansmen who were responsible for two political assassinations in Alamance and Caswell Counties. Both victims – one black, the other white – were Republican officeholders and civic leaders. A full report accompanies this letter as a supplement to materials submitted in support of our July 10 recommendation that the names of Charles Aycock, Julian Carr, Josephus Daniels, Thomas Ruffin, and Thomas Ruffin Jr. be removed from campus buildings. We believe that the information presented warrants an expedited review and removal of Thomas Ruffin Jr.’s name from Ruffin Residence Hall at the earliest possible date. This referral and the attached report were approved unanimously by commission members on July 30 in a poll conducted via e-mail. For the Commission, Patricia S. Parker James Leloudis Thomas Ruffin Jr. (1824 – 1889) This document supplements supporting materials that accompanied the July 10, 2020, recommendation from the Commission on History, Race, and a Way Forward that the names of Thomas Ruffin and Thomas Ruffin Jr. be removed from Ruffin Residence Hall. -

Thoughts on the Crucifixion Edward A

The Linacre Quarterly Volume 55 | Number 2 Article 16 May 1988 Why Did He Die in Three Hours?: Thoughts on the Crucifixion Edward A. Brucker Follow this and additional works at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq Recommended Citation Brucker, Edward A. (1988) "Why Did He Die in Three Hours?: Thoughts on the Crucifixion," The Linacre Quarterly: Vol. 55: No. 2, Article 16. Available at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq/vol55/iss2/16 Why Did He Die in Three Hours? Thoughts on the Crucifixion Edward A. Brucker, M.D. Doctor Brucker has served as director of laboratories at several hospitals and has, for the past 18 years, been a deputy medical examiner for Pima County in Arizona. He has studied and given lectures on the Shroud of Turinfor the past 27 years. Many problems exist with our understanding of crucifixion looking backward approximately 2,000 years. We know Constantine abolished crucifixions about 337 A. D. so that there is no known personal experience since that time of individuals reporting on crucifixions. Two events which add to our knowledge, however, and give us some insight as to how crucifixion was performed and what happened to the individual would be the Shroud of Turin which is probably the most important, and secondly, in 1968 in a Jewish cemetery - Givat ha M ivtar - in which the bones of a crucified individual, Johanaham, were identified with the nail being transfixed through the ankle bone and with scrape marks being identified on the radius bone. Other than these two events, we are limited to what the ancient historians and writers had to say about crucifixion. -

The Unauthorized Hagiography of Edward W. Hawkins

GOOD NIGHT, LADIES: THE UNAUTHORIZED HAGIOGRAPHY OF EDWARD W. HAWKINS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the College of English Morehead State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English by William Randolph Dozier 3 May 1997 Accepted by the faculty of the Caudill College of Humanities, Mo r ehead State University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in English Degr ee . Master' s Committee : Date GOOD NIGHT , LADIES: THE UNAUTHORIZED HAGIOGRAPHY OF EDWARD W. HAWKINS William Randolph Dozier, M. A. Morehead State University , 1997 Director of Thesis: 100% appr opriated texts have been aligned to form an author -free narrative-whole of rising and falling action which details the hanging of the outlaw Edward W. Hawkins in Estill County, Kentucky, on 29 May 1857 . Spanning 140 year s, the various documents, news accounts , ballads, and excerpts reconstitute Hawkins, a creature of dream, myth, and histor y . Hawkins is a type of Byronic hero, and the narrative traces his evolution from wanted fugitive to condemned prisoner to redeemed sinner . The competing texts of this assemblage differ in tone and particulars, thus creating a dynamic tension that pushes the narrative forward. The "hagiography" is an assault on the authority of the text, sacred and profane , and its message is simple : words arise from words. Accepted by: 1 invocation Oh, young reader, suffer me to exhort you to read the following pages with care and attention; they may serve you as a beacon by which you may escape the wretched condition which I am now in--incarcerated in the walls of a dungeon, loaded with chains and fetters, with the grim images of my murdered fellow-men haunting me day and night; and soon, oh! very soon, to be taken to the gallows, and there, in the spring season of my life, to be hurled into the presence of an offended God, who cannot look upon sin with the least allowance. -

Age Differences in Suicide Methods

Forensic Research & Criminology International Journal Research Article Open Access Age differences in suicide methods Abstract Volume 6 Issue 6 - 2018 Objective: There is not adequate research on suicide methods by age in Turkey. The purpose of the present study is to investigate whether there is any change in suicide methods Mustafa Demir by age over time and whether suicide methods significantly differ by age. State University of New York at Plattsburgh, USA Method: Secondary data about suicide from 2007 to 2015 were obtained from the Turkish Correspondence: Mustafa Demir, State University of New Statistical Institute. The number of suicide cases was 25,696. Direct standardization method York at Plattsburgh, USA, Tel +15185643305, was used to calculate suicide rates. Line charts were plotted to reveal the trends in suicide Email methods by age. Then, one-way anova (ANOVA) test was conducted to test whether suicide methods significantly differed by age. Received: June 05, 2017 | Published: December 11, 2018 Results: Among all ages, hanging was the most common suicide method, followed by firearm, jumping, intoxication, and cutting/burning among all age groups. Moreover, all of the other suicide methods increased except for cutting/burning among those aged 15- 24 years, except for firearm among those aged 25-44 years, except for hanging among those aged 45-64 years. Among those aged 65 and older, suicide by hanging decreased, however, suicide by other methods overall remained stable. The results also showed that with increasing age, suicide by hanging, jumping, and cutting increased, while suicide by firearm and intoxication decreased. In addition, the results of ANOVA test indicated that except for intoxication, all other suicide methods differed significantly by age groups. -

Tolerant Criminal Law of Rome in the Light of Legal and Rhetorical Sources

UWM Studia Prawnoustrojowe 25 189 2014 Artyku³y Przemys³aw Kubiak Katedra Prawa Rzymskiego Wydzia³ Prawa i Administracji Uniwersytetu £ódzkiego Some remarks on tolerant criminal law of Rome in the light of legal and rhetorical sources Introduction Roman criminal law, as majority of ancient legal systems, is commonly considered cruel and intolerant. Most of these negative views is based on the fact that the Romans created and used a great variety of painful and severe penalties, very often accompanied by different kinds of torture or disgrace1. Although such opinions derive from legal and literary sources, occasionally in their context a very important factor seems to be missing. Sometimes in the process of evaluation of foreign or historical legal systems researchers make a mistake and use modern standards, both legal and moral, and from this point of view they proclaim their statements. This incorrect attitude may lead to ascertainment that no legal system before 20th century should be judged positively in this aspect. However, the goal of this paper is not to change those statements, as they are based on sources, but rather to give examples and to underline some important achievements of Roman crimi- nal law which, sometimes forgotten or disregarded, should be considered in the process of its historical evaluation. 1 The most cruel are definitely aggravated forms of death penalty, such as crucifixion (crux), burning alive (vivi crematio), throwing to wild animals during the games (damnatio ad bestias), throwing to the sea in a sack with ritual animals (poena cullei). These are the most common, but during the history of Roman empire there existed many other severe kinds of capital punishment, see A.W. -

A Systematic Examination of the Rituals and Rights of the Last Meal

Mercer University School of Law Mercer Law School Digital Commons Faculty Publications Faculty 2014 Cold Comfort Food: A Systematic Examination of the Rituals and Rights of the Last Meal Sarah Gerwig-Moore Mercer University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.mercer.edu/fac_pubs Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Criminal Procedure Commons Recommended Citation Sarah L. Gerwig-Moore, et al., Cold Comfort Food: A Systematic Examination of the Rituals and Rights of the Last Meal, 2 Brit. J. Am. Legal Stud. 411 (2014). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty at Mercer Law School Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Mercer Law School Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COLD (COMFORT?) FOOD: THE SIGNIFICANCE OF LAST MEAL RITUALS IN THE UNITED STATES SARAH L. GERWIG-MOORE1 Merceer University School of Law ANDREW DAVIES2 State University of New York at Albany SABRINA ATKINS3 Baker, Donelson, Bearman, Caldwell & Berkowitz P. C ABSTRACT Last meals are a resilient ritual accompanying executions in the United States. Yet states vary considerably in the ways they administer last meals. This paper ex- plores the recent decision in Texas to abolish the tradition altogether. It seeks to understand, through consultation of historical and contemporary sources, what the ritual signifies. We then go on to analyze execution procedures in all 35 of the states that allowed executions in 2010, and show that last meal allowances are paradoxically at their most expansive in states traditionally associated with high rates of capital punishment (Texas now being the exception to that rule.) We con- clude with a discussion of the implications of last meal policies, their connections to state cultures, and the role that the last meal ritual continues to play in contem- porary execution procedures. -

Emergency Care of the Crucifixion Victim

Accident and Emergency Nursing (2002) 10, 235–239 ª 2002 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/S0965-2302(02)00127-3, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on Emergency care of the crucifixion victim Scott L DeBoer, Charles L Maddow ... of all punishments, it is the most cruel and most terrifying Cicero, first century A.D. Of all the terrible ways to die, most people say that death by fire or death by drowning are the worst. If you lived 2000 years ago however, you most certainly would disagree. Throughout world history, one of the most feared deaths was that of crucifixion. This article will guide you through the medical, psychological, and emotional aspects of crucifixion. The death of the man called Jesus Christ will be used to illustrate the use of a punishment that was unequalled in its cruelty and depth of suffering. This article will review not only the injuries associated with crucifixion, as well as current medical archaeological theories relating to the suffering and eventual death on a cross, but Scott L DeBoer also using the introduction case study, the initial assessment and resuscitation of a crucifixion RN,MSN,CEN,CCRN, CFRN Flight Nurse victim will be addressed. Regardless of religious beliefs, this article will give attendees a Educator: UCAN, deeper awareness of ‘‘and they crucified him’’. ª 2002 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights University of Chicago Hospitals, reserved. Owner: Peds-R-Us Medical Education, Chicago, Illinois USA Charles L Maddow ... MD, Senior Medic 101 to County General We are en route it still is being performed as evidenced by the Instructor of with a 33-year old male who was the victim of a current practice in areas of the Philippines, Emergency crucifixion. -

Crucifixion in Antiquity: an Inquiry Into the Background and Significance of the New Testament Terminology of Crucifixion

GUNNAR SAMUELSSON Crucifixion in Antiquity Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 2. Reihe 310 Mohr Siebeck Gunnar Samuelsson questions the textual basis for our knowledge about the death of Jesus. As a matter of fact, the New Testament texts offer only a brief description of the punishment that has influenced a whole world. ISBN 978-3-16-150694-9 Mohr Siebeck Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament · 2. Reihe Herausgeber / Editor Jörg Frey (Zürich) Mitherausgeber / Associate Editors Friedrich Avemarie (Marburg) Markus Bockmuehl (Oxford) James A. Kelhoffer (Uppsala) Hans-Josef Klauck (Chicago, IL) 310 Gunnar Samuelsson Crucifixion in Antiquity An Inquiry into the Background and Significance of the New Testament Terminology of Crucifixion Mohr Siebeck GUNNAR SAMUELSSON, born 1966; 1992 Pastor and Missionary Degree; 1997 B.A. and M.Th. at the University of Gothenburg; 2000 Μ. Α.; 2010 ThD; Senior Lecturer in New Testament Studies at the Department of Literature, History of Ideas and Religion, University of Gothenburg. ISBN 978-3-16-150694-9 ISSN 0340-9570 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament, 2. Reihe) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbiblio graphie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. ©2011 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed by Laupp & Göbel in Nehren on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Nadele in Nehren. -

The Spanish Garrote

he members of parliament, meeting in Cadiz in 1812, to draft the first Spanish os diputados reunidos en Cádiz en 1812 para redactar la primera Constitución Constitution, were sensitive to the irrational torment that those condemned to Española, fueron sensibles a los irracionales padecimientos que hasta entonces capital punishment had up until then suffered when they were punished. In De- the spanish garrote sufrían los condenados a la pena capital en el momento de ser ajusticiados, y cree CXXVIII, of 24 January, they recognized that “no punishment will be trans- en el Decreto CXXVIII, de 24 de enero, reconocieron que “ninguna pena ha ferable to the family of the person that suffers it; and wishing at the same time that Lde ser trascendental a la familia del que la sufre; y queriendo al mismo tiempo Tthe torment of the criminals should not offer too repugnant a spectacle to humanity que el suplicio de los delincuentes no ofrezca un espectáculo demasiado and to the generous nature of the Spanish nation (…) ” they agreed to abolish the repugnante a la humanidad y al carácter generoso de la Nación española transferable punishment of hanging, replacing it with the garrote. (...) ” acordaron abolir la trascendental pena de horca, sustituyéndola por la Some days earlier, on January 10th, the City Council of Toledo, in compliance de garrote. with a decision of the Real Junta Criminal [Royal Criminal Committee] of the city, Ya unos días antes, el 10 de enero, el ayuntamiento de Toledo, en cum- agreed to the construction of two garrotes and approved the regulations for the plimiento de una providencia de la Real Junta Criminal de la ciudad, acordó construction of the platform. -

Seven Days Before the Crucifixion

THE LAST WEEK OF OUR LORD’S MINISTRY WITH TEXTS AND ARTICLES FOR EACH DAY’S READING 7 days before Passover. Traveling toward Jerusalem. Matt. 20:17-28; Luke 18:35-43; 19:1-10; R. 3362 (Z ’04-138); R. 3847 (Z ’06-278). 6 days before Passover. Jesus came to Bethany and in the evening Mary anointed our Lord. John 12:1-8; Mark 14:3-9; Matt. Matthew 26:6-12. R. 2447 (Z ’99-76); R. 3534 (Z ’05-103). 5 days before Passover. They strewed palm branches; He rode into Jerusalem. Matt. 21:1-16; 23:37-39; Psa. 8:2; Luke 19:40. R. 3537 (Z ’05-108); R. 2745 (Z’00-380); R. 3850 (Z ’06-281). 4 days before Passover. Cursing of fig tree; cleansing of Temple; He taught the people there. Matt. 21:17-32; Mark 11:12-19; John 2:13-22. R. 5503 (Z ’14-219); R. 5920 (Z ’16-204); R. 4122 (Z ’08-25). 3 days before Passover. Teaching in Temple; challenged with questions; tried to catch Him in His words. Many parables given on this day. Matt. 22:15-46; 23:14-39; 25:1-13. R. 3852, (Z ’06-284); R. 1982 (Z ’96-115); R. 2746, c. 2, p. 2-3 (Many of His parables given) = (Z ’00-382, c. 1, p. 1). 2 days before Passover. There is no record of the events of this day; it was probably spent in retirement at Bethany. R. 3542, c. 1, p. 7 (Z ’05-118); R.