Blended Frameworks in the Works of Poe, Hawthorne, and Dickinson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2-22- the Four Last Things

St. Mark Seeker’s Study Guide February 22, 2017: The Four Last Things – Death, Judgment, Heaven and Hell The Four Last Things, death, judgment, heaven and hell, are realities of human life. Although our end in this world is not the most attractive topic of conversation, Christians should understand that death is a passage to new life. The Communion of the Saints is the unity of baptized Christians with all who have gone before us in the oneness of God. As Christians, we don’t just prepare for death, but we live that new life today in the sanctifying grace of our God. As we consider the Four Last things, we should do so in the context of faith. Death The Christian Life and Death: The dying should be given attention and care to help them live their last moments in dignity and peace. Assisted suicide or euthanasia are not a morally responsible use of life. The dying should be accompanied and supported. No one ought to feel that they are a burden to others. Part of the challenge of the spiritual life is to both learn to love and to be loved. Why is it harder to be loved? Prayer for the Dying: The dying will be helped by the prayer of their relatives, who must see to it that the sick receive at the proper time the Sacraments that prepare them to meet the living God” (CCC, no. 2299). Death: The final article of the Creed proclaims our belief in everlasting life. At the Catholic Rite of Commendation of the Dying, sometimes prayed at the Anointing of the Sick, we sometimes hear this prayer: “Go forth, Christian soul, from this world... -

PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - Animation Auction 52A, Auction Date: 12/1/2012

26901 Agoura Road, Suite 150, Calabasas Hills, CA 91301 Tel: 310.859.7701 Fax: 310.859.3842 PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - Animation Auction 52A, Auction Date: 12/1/2012 LOT ITEM PRICE 4 X-MEN “OLD SOLDIERS”, (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND $275 FEATURING “CAPTAIN AMERICA” & “WOLVERINE”. 5 X-MEN “OLD SOLDIERS”, (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND $200 FEATURING “CAPTAIN AMERICA” & “WOLVERINE” FIGHTING BAD GUYS. 6 X-MEN “PHOENIX SAGA (PART 3) CRY OF THE BANSHEE”, ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CEL $100 AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “ERIK THE REDD”. 8 X-MEN OVERSIZED ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CEL AND BACKGROUND FEATURING $150 “GAMBIT”, “ROGUE”, “PROFESSOR X” & “JUBILEE”. 9 X-MEN “WEAPON X, LIES, AND VIDEOTAPE”, (3) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND $225 BACKGROUND FEATURING “WOLVERINE” IN WEAPON X CHAMBER. 16 X-MEN ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CEL AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “BEAST”. $100 17 X-MEN (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “NASTY BOYS”, $100 “SLAB” & “HAIRBAG”. 21 X-MEN (3) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “STORM”. $100 23 X-MEN (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND (2) SKETCHES FEATURING CYCLOPS’ $125 VISION OF JEAN GREY AS “PHOENIX”. 24 X-MEN (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “CAPTAIN $150 AMERICA” AND “WOLVERINE”. 25 X-MEN (9) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND PAN BACKGROUND FEATURING “CAPTAIN $175 AMERICA” AND “WOLVERINE”. 27 X-MEN (3) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “STORM”, $100 “ROGUE” AND “DARKSTAR” FLYING. 31 X-MEN THE ANIMATED SERIES, (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND $100 FEATURING “PROFESSOR X” AND “2 SENTINELS”. 35 X-MEN (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION PAN CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING $100 “WOLVERINE”, “ROGUE” AND “NIGHTCRAWLER”. -

Part 1--The Remembrance of Death

Part 1--The Remembrance of Death Part 1--The Remembrance of Death A TREATISE (UNFINISHED) UPON THESE WORDS OF HOLY SCRIPTURE Memorare novissima, & in aeternum non peccabis “Remember the last things, & thou shalt never sin.”—Ecclus. 7 . Made about the year of our Lord 1522, by Sir Thomas More then knight, and one of the Privy Council of King Henry VIII, and also Under-Treasurer of England. If there were any question among men whether the words of holy Scripture or the doctrine of any secular author were of greater force and effect to the weal and profit of man’s soul (though we should let pass so many short and weighty words spoken by the mouth of our Saviour Christ Himself, to Whose heavenly wisdom the wit of none earthly creature can be comparable) yet this only text written by the wise man in the seventh chapter of Ecclesiasticus is such that it containeth more fruitful advice and counsel to the forming and framing of man’s manners in virtue and avoiding of sin, than many whole and great volumes of the best of old philosophers or any other that ever wrote in secular literature. Long would it be to take the best of their words and compare it with these words of holy Writ. Let us consider the fruit and profit of this in itself: which thing, well advised and pondered, shall well declare that of none whole volume of secular literature shall arise so very fruitful doctrine. For what would a man give for a sure medicine that were of such strength that it should all his life keep him from sickness, namely 1 if he might by the avoiding of sickness be sure to continue his life one hundred years? So is it now that these words giveth us all a sure medicine (if we forsloth 2 not the receiving) by which we shall keep from sickness, not the body, which none health may long keep from death (for die we must in few years, live we never so long), but the soul, which here preserved from the sickness of sin, shall after this eternally live in joy and be preserved from the deadly life of everlasting pain. -

A Re-Examination of Luther's View on the State of the Dead

Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 22/2 (2011):154-170. Article copyright © 2011 by Trevor O’Reggio. A Re-examination of Luther’s View on the State of the Dead Trevor O’Reggio Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Andrews University Introduction Luther’s theology was forged in the crucible of his struggle to find forgiveness and peace from his overwhelming sense of guilt. He had an acute sense of misery and felt as if he hung in the balance between life and death. The German word that captures something of Luther’s emotional state is Anfechtung—one feels cut off from God and hope is suffocated. “Anfechtung is the foretaste of the peril of death.”1 It was not only the fear of death that terrorized him, but death itself was an ever-present reality for Luther. He lost two of his children in childhood, so by virtue of his experience, and his theology, he was forced to wrestle with the meaning of death and the after-life. It is not surprising then that Luther wrote much about death, some of it at times confusing and complicated. Did Luther believe in soul sleep or in an immortal soul that survives death? There are generally two views concerning the state of the dead among Christians. The first view asserts that when a person dies, his soul survives death and continues to exist in some place. For those who are saved, they go straight into paradise. For those who are not so righteous, they go into some halfway house called purgatory (Catholic view) where they are purified and made ready for paradise. -

Melee Weapons, Ranged Weapons, Special Issue Wargear, Or Relics May Purchase a Zephyr Command Module As a Dedicated Transport

Codex: Ornthon v 1.0 A Galaxy Lost The story of the Ornthon race did not begin in this galaxy. Once they were native to a galaxy far away. But that would all come to change with the arrival of a menace from the stars. Scattered like chaff upon the wind, the Ornthon Heirs to a Galaxy race struggles to survive far from their true As far back as they have record, the Ornthon home. New aeries grow upon worlds here and race has always been filled with ambition. From there across the galaxy as survivors struggle to the first time they reached out to the stars, they rebuild glory now lost. The voices of ancestors knew themselves to be destined for greatness. cry out for vengeance even as voices from the This attitude permeates the entire racial deep whisper dreams of power. The Ornthon culture, and for a long time would seem to be race is in a fight for both survival in the galaxy, truth. and for control of a rapidly dividing culture. As they struck out into the larger galaxy the Once, things were not so. In time past and far race spread with a zeal that was unmatched by away the Ornthon knew peace and prosperity. their neighbors. The stories tell of battles, wars, Their race was first among equals and oversaw treaties, and assimilation. Heroes arose and fell vast swathes of the stars. In that time their race as an empire was forged. By the time the other was not divided, but acted as one for the great races had come risen up the Ornthon had betterment of all. -

Metaphysical Reflections on Human Personhood

CHAP1.fm Page 15 Wednesday, August 2, 2000 3:03 PM Part One Metaphysical Reflections on Human Personhood CHAP1.fm Page 16 Wednesday, August 2, 2000 3:03 PM Throughout the centuries Christians have believed that each human person consists in a soul and body; that the soul survived the death of the body; and that its future life will be immortal.1 H. D. LEWIS In terms of biblical psychology, man does not have a “soul,” he is one. He is a living and vital whole. It is possible to distinguish between his activities, but we cannot distinguish between the parts, for they have no independent existence.2 J. K. HOWARD How should we think about human persons? What sorts of things, fundamentally, are they? What is it to be a human, what is it to be a human person, and how should we think about personhood? . The first point to note is that on the Christian scheme of things, God is the premier person, the first and chief exemplar of personhood . and the properties most important for an understanding of our personhood are properties we share with him.3 A LVIN PLANTINGA CHAP1.fm Page 17 Wednesday, August 2, 2000 3:03 PM CHAPTER 1 Establishing a Framework for Approaching Human Personhood ................................................... ........................ T IS SAFE TO SAY THAT THROUGHOUT HUMAN HISTORY, THE VAST majority of people, educated and uneducated alike, have been dual- I ists, at least in the sense that they have taken a human to be the sort of being that could enter life after death while one’s corpse was left behind—for example, one could enter life after death as the very same individual or as some sort of spiritual entity that merges with the All. -

Antigone and Literary Criticism

Summer Reading English II Honors Antigone and Literary Criticism English II Honors students are required to complete the posted reading over the summer and come to class prepared to discuss the critical issues raised in the essays about the play Antigone. A suggested reading order is as follows: “Antigone Synopsis” “Introduction to Antigone” Antigone (text provided in .pdf form) “Antigone Commentary” It is recommended that students print out hard copies of the three critical essays for note-taking purposes; a hard copy of the complete text of Antigone will be provided the first week of class, so there is no need to print the entire play. Student Goals: to familiarize yourself with Antigone, Greek Drama, and literary criticism prior to the first day of class; to demonstrate critical thinking and writing skills the first week of class. See you in August!. Mr. Gordon 5/13/2019 History - Print - Introduction to <em>Antigone</em> Bloom's Literature Introduction to Antigone I. Author and Background It seems that in March, 441 B.C., the Antigone made Sophocles famous. The poet, fifty-five years old, had now produced thirty-two plays; because of this one, tradition relates, the people of Athens elected him, the next year, to high office. We hear he shared the command of the second fleet sent to Samos. When the people of Samos failed to support the government just established for them by forty Athenian ships, Athens sent a fleet of sixty ships to restore democracy and remove the rebels. The Aegean then was an Athenian sea. Pericles, the great political leader and advocate of firm alliance, was first in command. -

Thoughts on the Crucifixion Edward A

The Linacre Quarterly Volume 55 | Number 2 Article 16 May 1988 Why Did He Die in Three Hours?: Thoughts on the Crucifixion Edward A. Brucker Follow this and additional works at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq Recommended Citation Brucker, Edward A. (1988) "Why Did He Die in Three Hours?: Thoughts on the Crucifixion," The Linacre Quarterly: Vol. 55: No. 2, Article 16. Available at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq/vol55/iss2/16 Why Did He Die in Three Hours? Thoughts on the Crucifixion Edward A. Brucker, M.D. Doctor Brucker has served as director of laboratories at several hospitals and has, for the past 18 years, been a deputy medical examiner for Pima County in Arizona. He has studied and given lectures on the Shroud of Turinfor the past 27 years. Many problems exist with our understanding of crucifixion looking backward approximately 2,000 years. We know Constantine abolished crucifixions about 337 A. D. so that there is no known personal experience since that time of individuals reporting on crucifixions. Two events which add to our knowledge, however, and give us some insight as to how crucifixion was performed and what happened to the individual would be the Shroud of Turin which is probably the most important, and secondly, in 1968 in a Jewish cemetery - Givat ha M ivtar - in which the bones of a crucified individual, Johanaham, were identified with the nail being transfixed through the ankle bone and with scrape marks being identified on the radius bone. Other than these two events, we are limited to what the ancient historians and writers had to say about crucifixion. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES English Behind Apocalypse The Cultural Legacy of 9/11 by Matthew Stuart Leggatt Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT HUMANITIES English Doctor of Philosophy BEHIND APOCALYPSE THE CULTURAL LEGACY OF 9/11 by Matthew Stuart Leggatt ‘Part One: 9/11 and the Death of the Capitalist Utopia’ focuses on how 9/11 has been memorialised, mythologised, and mobilised by contemporary culture. It examines a range of cultural materials from literature, film, and architecture, to 9/11 in the media. The section discusses, through a fusion of cultural and political thought, how the War on Terror became the inevitable continuation of the binary rhetoric of good and evil perpetuated since 9/11. -

Appendix 8 — Formulas of Catholic Doctrine

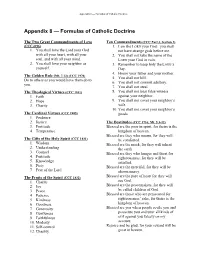

Appendix 8 — Formulas of Catholic Doctrine Appendix 8 — Formulas of Catholic Doctrine The Two Great Commandments of Love Ten Commandments (CCC Part 3, Section 2) (CCC 2196) 1. I am the LORD your God: you shall 1. You shall love the Lord your God not have strange gods before me. with all your heart, with all your 2. You shall not take the name of the soul, and with all your mind. LORD your God in vain. 2. You shall love your neighbor as 3. Remember to keep holy the LORD’s yourself. Day. 4. Honor your father and your mother. The Golden Rule (Mt. 7:12) (CCC 1970) 5. You shall not kill. Do to others as you would have them do to 6. You shall not commit adultery. you. 7. You shall not steal. The Theological Virtues (CCC 1841) 8. You shall not bear false witness 1. Faith against your neighbor. 2. Hope 9. You shall not covet your neighbor’s 3. Charity wife. 10. You shall not covet your neighbor’s The Cardinal Virtues (CCC 1805) goods. 1. Prudence 2. Justice The Beatitudes (CCC 1716; Mt. 5:3-12) 3. Fortitude Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the 4. Temperance kingdom of heaven. Blessed are they who mourn, for they will The Gifts of the Holy Spirit (CCC 1831) be comforted. 1. Wisdom Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit 2. Understanding the earth. 3. Counsel Blessed are they who hunger and thirst for 4. Fortitude righteousness, for they will be 5. Knowledge satisfied. -

Pleasures of Gluttony Los Placeres De La Codicia Os Prazeres Da Gula

Pleasures of Gluttony Los placeres de la Codicia Os prazeres da Gula Burçin EROL 1 Abstract: In the late Middle Ages, especially in England, displaying an abundance of food and feasting became not only an act of pleasure but also a means of establishing status and wealth, despite gluttony being one of the seven deadly sins. In the fourteenth century – due to various reasons such as increased population, crop failure, the Black Death, and the disruption of food production by warfare – feasting, the displaying of food, and indulgence in gluttony was an indicator of wealth, riches, and high status for the upper class or the social climber as it is well indicated in the works of Chaucer and some of his contemporaries. Resumo: Especialmente na Idade Média Tardia, na Inglaterra, demonstrações de comida abundante e ceias se tornaram não somente um prazer, mas uma representação do estabelecimento de status e riqueza, apesar da gula ser proclamada um dos sete pecados capitais. No século XIV, devido a várias calamidades, como crescimento populacional, problemas na colheita , a peste negra e a quebra da produção de comida, o fornecimento e a ostentação de comida e indulgencia na gula foi um indicador de riqueza grande status para a classe alta ou para ascendentes sociais, como bem indicada nos trabalhos de Chaucer e alguns de seus contemporâneos. Keywords: Seven Deadly Sins – Gluttony – Pleasure – Middle English Literature. Palavras-chaves: Sete Pecados Capitais – Gula – Prazer – Literatura em Inglês Médio. 1 Prof. Dr., Department of English Language and Literature, Faculty of Letters, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected] . -

What Happens After Death According to the Hymns in the LSB

What Happens after Death According to the Hymns in the LSB What follows is meant to be proactive, meaning that I intend it to be a guide for those who write hymn texts and for those who select hymns for publication in the future, rather than a critique of texts that have been written and published in the past. I have wanted to do a study like this ever since seminary days when I heard professor Arthur Carl Piepkorn say that the laity in our Church get their theology primarily from hymns. That struck me as true then, and I think it is still true today. If it is true, then what follows should be of interest to anyone who writes hymns texts, translates them from other languages, edits earlier translations, selects hymn texts for publication, or reviews them for doctrinal correctness, as well as to everyone who uses them in worship, mediation or prayer. In my own case, before I got to the seminary, I believed that at death believers go immediately to heaven in the full sense of the word, a belief held by many of our lay people and many pastors. This is not surprising since the Book of Concord, which we believe is a correct and authoritative interpretation of the Sacred Scriptures, states: “We grant that the angels pray for us . We also grant that the saints in heaven (in coelis, im Himmel) pray for the church in general, as they prayed for the church while they were on earth. But neither a command nor a promise nor an example can be shown from Scripture for the invocation of the saints; from this it follows that consciences cannot be sure about such invocation.” (My italics.