2014 Moody Simon 1063185

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suez 1956 24 Planning the Intervention 26 During the Intervention 35 After the Intervention 43 Musketeer Learning 55

Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd i 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iiii 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East Louise Kettle 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iiiiii 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Louise Kettle, 2018 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road, 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry, Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/1 3 Adobe Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain. A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 3795 0 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 3797 4 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 3798 1 (epub) The right of Louise Kettle to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iivv 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Contents Acknowledgements vii 1. Learning from History 1 Learning from History in Whitehall 3 Politicians Learning from History 8 Learning from the History of Military Interventions 9 How Do We Learn? 13 What is Learning from History? 15 Who Learns from History? 16 The Learning Process 18 Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East 21 2. -

The Rhodesian Crisis in British and International Politics, 1964

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE RHODESIAN CRISIS IN BRITISH AND INTERNATIONAL POLITICS, 1964-1965 by CARL PETER WATTS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Historical Studies The University of Birmingham April 2006 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis uses evidence from British and international archives to examine the events leading up to Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) on 11 November 1965 from the perspectives of Britain, the Old Commonwealth (Canada, Australia, and New Zealand), and the United States. Two underlying themes run throughout the thesis. First, it argues that although the problem of Rhodesian independence was highly complex, a UDI was by no means inevitable. There were courses of action that were dismissed or remained under explored (especially in Britain, but also in the Old Commonwealth, and the United States), which could have been pursued further and may have prevented a UDI. -

Hvestowm Air Force A-Bomber Weapons Again Refuses U.N. Lea

back irom Main St, nearly 60 feet. It Is expected it will Im completed About Town in June, Heard Along Main Street Mr. Burr’a father waa greatly Buasat 'Council, Ko^. 45, Dagrea interested in trees and ahrubs, and. of Pocabontaa, will hold a bua(- his “son, brought up -in the busi naaa meating Monday at 8 p.m. And on Sontf of Manchester*s*lSide SireetSt Too ness. bought the Hubbard farm on The Paraonnal Pollclaf Oomrhit- in Tinkar Hall. , NominaUon of, Oakland St. in 1898 and started on teea of the'Manchester Education offlcera will t ^ a place and plans, Anybody In the Aonghf >VConn.. ...” What an intoxicating his o^'n, m aki'g hlS',.home in Aten, and the Board of Education will be mada for the annual ,Here is a random selection of thought that is. Hartford. On Sept. 20, 1900, he will meet aoon to dTscusa teacher Christmas party, . puns which have grown out of the married Mias Calls. Hickox of requesta for an Increased . wage controversy over the golf course. All That Glitters Durham. Years later, he bought, hike and other benefits. '% Sunaat Rebakah Lodge, No.' 39, When the negotiators for both The latest, If you haveA't heard from the late Henry L. Vibberta No. date' has been set for the W* Hove Gkifs Wax a t will meat Monday'kt 8 p.m. in sides were trying to agree on w hat! yet, is making your own -decora- the Judge Campbell House, so meeting, but It is expected to be igh Odd Fellows Halir The seebnd a fair price for use of the course i tion? fop Christmas, called, which they occupied until held'Within the next. -

1 Introduction 1

Notes 1 Introduction 1. A debate exists whether a ‘Second Cold War’ did in fact break out or whether this merely a changing phase of the ongoing Cold War. This changing situation in East-West relations from the late 1970s onwards will henceforth, be referred to as the Second Cold War. See, for example, Fred Halliday, The Making of the Second Cold War (London: Verso Editions and NLB, second edition, 1986). 2. Private discussions. In 1979 only 2 per cent of the electorate thought defence was a major issue in the election. By 1983 this had risen to 38 per cent. Michael Heseltine, ‘The United Kingdom’s Strategic Interests and Priorities’, RUSI Journal, vol. 128, no. 4, December 1983, pp. 3–5, p. 3. The 1983 election campaign was noteworthy for the action of the previous Labour Prime Minister, James Callaghan, who took the unprecedented step of repudiating his own party’s defence policy; Ian Aitken, ‘Callaghan Wrecks Polaris Repairs’, Guardian, 26 May 1983; Peter M. Jones, ‘British Defence Policy: the Breakdown of the Inter-party Consensus’, Review of International Studies, vol. 13, no. 2, April 1987, pp. 111–31; Bruce George and Curt Pawlisch, ‘Defence and 1983 Election’, ADIU Report, vol. 5, no. 4, July/August 1983, p. 2; Michael Heseltine, Life in the Jungle: My Autobiography (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2000), p. 250. 3. Peter Calvocoressi, ‘Deterrence, the Costs, the Issues, the Choices’, Sunday Times, 6 April 1980. 4. Nicholas J. Wheeler, ‘Perceptions of the Soviet Threat’, in British Security Policy: the Thatcher Years and the End of the Cold War, edited by Stuart Croft (London: HarperCollins Academic, 1991), p. -

Andrew Dorman Michael D. Kandiah and Gillian Staerck ICBH Witness

edited by Andrew Dorman Michael D. Kandiah and Gillian Staerck ICBH Witness Seminar Programme The Nott Review The ICBH is grateful to the Ministry of Defence for help with the costs of producing and editing this seminar for publication The analysis, opinions and conclusions expressed or implied in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the JSCSC, the UK Ministry of Defence, any other Government agency or the ICBH. ICBH Witness Seminar Programme Programme Director: Dr Michael D. Kandiah © Institute of Contemporary British History, 2002 All rights reserved. This material is made available for use for personal research and study. We give per- mission for the entire files to be downloaded to your computer for such personal use only. For reproduction or further distribution of all or part of the file (except as constitutes fair dealing), permission must be sought from ICBH. Published by Institute of Contemporary British History Institute of Historical Research School of Advanced Study University of London Malet St London WC1E 7HU ISBN: 1 871348 72 2 The Nott Review (Cmnd 8288, The UK Defence Programme: The Way Forward) Held 20 June 2001, 2 p.m. – 6 p.m. Joint Services Command and Staff College Watchfield (near Swindon), Wiltshire Chaired by Geoffrey Till Paper by Andrew Dorman Seminar edited by Andrew Dorman, Michael D. Kandiah and Gillian Staerck Seminar organised by ICBH in conjunction with Defence Studies, King’s College London, and the Joint Service Command and Staff College, Ministry of -

ORDERS, DECORATIONS, MEDALS and MILITARIA 19 MAY 2021

DIX • NOONAN • WEBB ORDERS, DECORATIONS, MEDALS and MILITARIA 19 MAY 2021 19 MAY and MILITARIA MEDALS WEBB ORDERS, DECORATIONS, • DIX • NOONAN Orders, Decorations, Medals and Militaria including The important Second War D.S.O., D.F.C. and Bar group of seven awarded to Battle of Britain Pilot Group Captain Brian Kingcome, Royal Air Force and www.dnw.co.uk A Collection of Medals to the 13th, 18th and 13th/18th Hussars, Part 1 16 Bolton Street Mayfair London W1J 8BQ Telephone 020 7016 1700 Email [email protected] Wednesday 19th May 2021 at 10:00am BOARD OF DIRECTORS Pierce Noonan Chairman and CEO Robin Greville Chief Technology Officer Nimrod Dix Deputy Chairman Christopher Webb Director (Numismatics) AUCTION AND CLIENT SERVICES Philippa Healy Head of Administration (Associate Director) 020 7016 1775 [email protected] Emma Oxley Accounts and Viewing 020 7016 1701 [email protected] Anna Gumola Accounts and Viewing 020 7016 1701 [email protected] Christopher Mellor-Hill Head of Client Liaison (Associate Director) 020 7016 1771 [email protected] Chris Finch Hatton Client Liaison 020 7016 1754 [email protected] James King Saleroom and Facilities Manager 020 7016 1755 [email protected] Lee King Logistics and Shipping Manager 020 7016 1756 [email protected] MEDALS AND MILITARIA Nimrod Dix Head of Department (Director) 020 7016 1820 [email protected] Oliver Pepys Specialist (Associate Director) 020 7016 1811 [email protected] Mark Quayle Specialist (Associate Director) 020 7016 1810 [email protected] Dixon Pickup Consultant (Militaria) 020 7016 1700 [email protected] -

The London Gazette of Monday, 28Th June 1976 Bp

No. 46947 8989 SUPPLEMENT TO The London Gazette of Monday, 28th June 1976 bp Registered as a Newspaper TUESDAY, 29ra JUNE 1976 MINISTRY OF DEFENCE ARMY DEPARTMENT Short Serv. Commit. 2nd Lt. The Duke of ROXBURGHE (498248) to be Lt., 29th June 1976. 29th Jun. 1976. Gen. Sir Roland GIBBS, G.C.B., C.B.E., D.S.O., M.C., ROYAL ARMOURED CORPS (114083) Colonel Commandant, 2nd Battalion The Royal Green Jackets, Colonel Commandant, The Parachute REGULAR ARMY Regiment is appointed Aide-de-Camp General to The The undermentioned 2nd Lts. to be Lts., 29th Jun. QUEEN, 25th Jun. 1976, in succession to Gen. Sir Cecil 1976: % BLACKER, G.C.B., O.B.E., M.C. (67083) Colonel, 5th J. S. BLACKETT (498143) 15/19 H. Royal Inniskilling Dragoon Guards, Colonel Com- L. DUCKWORTH (497406) 5 INNIS. D.G. mandant, Corps of Royal Military Police, Colonel Com- J. R. LEMON (498174) R.T.R. mandant, Army Physical Training Corps, tenure expired. S. R. LOGAN (498175) R.T.R. Special Reg. Commits. COMMANDS AND STAFF 2nd Lt. G. R. A. POTTER (498185) 5 INNIS. D.G. to be REGULAR ARMY Lt., 29th Jun. 1976. Gen. Sir Cecil BLACKER, G.C.B., O.B.E., M.C., 2nd Lt. R. C. SUTTON (498201) 4/7 D.G. to be Lt., (67083) late R.A.C. relinquishes the appointment of 29th Jun. 1976. Adjutant-General, Ministry of Defence,. 25th Jun. 1976. Short Serv. Commits. Lt.-Gen. (Local Gen.) Sir Edwin BRAMALL, K.C.B., The undermentioned 2nd Lts. to be Lts., 29th Jun. -

Battle Atlas of the Falklands War 1982

ACLARACION DE www.radarmalvinas.com.ar El presente escrito en PDF es transcripción de la versión para internet del libro BATTLE ATLAS OF THE FALKLANDS WAR 1982 by Land, Sea, and Air de GORDON SMITH, publicado por Ian Allan en 1989, y revisado en 2006 Usted puede acceder al mismo en el sitio www.naval-history.com Ha sido transcripto a PDF y colocado en el sitio del radar Malvinas al sólo efecto de preservarlo como documento histórico y asegurar su acceso en caso de que su archivo o su sitio no continúen en internet, ya que la información que contiene sobre los desplazamientos de los medios británicos y su cronología resultan sumamente útiles como información británica a confrontar al analizar lo expresado en los diferentes informes argentinos. A efectos de preservar los derechos de edición, se puede bajar y guardar para leerlo en pantalla como si fuera un libro prestado por una biblioteca, pero no se puede copiar, editar o imprimir. Copyright © Penarth: Naval–History.Net, 2006, International Journal of Naval History, 2008 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- BATTLE ATLAS OF THE FALKLANDS WAR 1982 NAVAL-HISTORY.NET GORDON SMITH BATTLE ATLAS of the FALKLANDS WAR 1982 by Land, Sea and Air by Gordon Smith HMS Plymouth, frigate (Courtesy MOD (Navy) PAG Introduction & Original Introduction & Note to 006 Based Notes Internet Page on the Reading notes & abbreviations 008 book People, places, events, forces 012 by Gordon Smith, Argentine 1. Falkland Islands 021 Invasion and British 2. Argentina 022 published by Ian Allan 1989 Response 3. History of Falklands dispute 023 4. South Georgia invasion 025 5. -

![Revue Historique Des Armées, 273 | 2014, « Les Coalitions » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 10 Mai 2014, Consulté Le 25 Février 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0251/revue-historique-des-arm%C3%A9es-273-2014-%C2%AB-les-coalitions-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-10-mai-2014-consult%C3%A9-le-25-f%C3%A9vrier-2020-3390251.webp)

Revue Historique Des Armées, 273 | 2014, « Les Coalitions » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 10 Mai 2014, Consulté Le 25 Février 2020

Revue historique des armées 273 | 2014 Les coalitions Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rha/7865 ISSN : 1965-0779 Éditeur Service historique de la Défense Référence électronique Revue historique des armées, 273 | 2014, « Les coalitions » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 10 mai 2014, consulté le 25 février 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rha/7865 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 25 février 2020. © Revue historique des armées 1 Éditorial Revue historique des armées, 273 | 2014 2 Éditorial 1 Éditorial 2 Colonel Jean-Marc Marill, 3 docteur en histoire, rédacteur en chef 4 Le dossier éponyme de ce numéro de la Revue historique des armées est consacré aux « coalitions ». Les articles qui le composent concernent de vastes zones géographiques allant de l’Amérique du Sud à l’Europe et au Moyen-Orient. La séquence chronologique, quant à elle, s’étend du XIXe au XXI e siècle. Les caractéristiques des guerres de coalitions ont déjà été décrites par l’historien antique Thucydide. La guerre du Péloponnèse ou deux blocs s’affrontèrent sous l’égide des deux plus puissantes cités du monde grec - la ligue attico-délienne et la ligue péloponnésienne - a en effet expérimenté toutes les formes et toutes les vicissitudes d’une guerre de coalitions. Des grandes batailles navales et terrestres, des phases de combats de basse intensité, des actions subversives, des intérêts stratégiques divergeant au sein des blocs ont caractérisé ce long conflit. Ainsi les guerres de coalitions ont d’emblée couvert l’ensemble du spectre des conflits allant de la guerre généralisée impliquant l’engagement d’armées puissantes et nombreuses, au combat de basse, voire de très basse intensité mettant en jeu des forces aux effectifs réduits et mal équipés ainsi que le montre l’article « Guerre et alliances en Amérique du Sud » du professeur émérite Marie-Danielle Demélas. -

Preface 1 Introduction

Notes Preface 1. Basil Liddell Hart, The British Way in Warfare (New York: Macmillan, 1933), Chapter 1, ‘The Historical Strategy of Britain’. Liddell Hart’s treatise was writ- ten in reaction to Britain’s costly participation on the Western Front during the Great War; for Michael Howard’s interpretation, see ‘The British Way in Warfare: A Reappraisal’, in The Causes of Wars, and Other Essays (Boston: Unwin Paperbacks, 1985), p. 200. 1 Introduction 1. Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000 (New York: Random House, 1987); Philip Darby, British Defence Policy East of Suez 1947 to 1968 (London: OUP for RIIA, 1973); Nicholas Tarling, The Fall of Imperial Britain in South-East Asia (London: OUP, 1993); Correlli Barnett, The Lost Victory: British Dreams, British Realities 1945–1950 (London: Macmillan Press–now Palgrave, 1995). 2. Barnett condensed this argument for his 1995 presentation to the RUSI. See ‘The British Illusion of World Power, 1945–1950,’ The RUSI Journal, 140:5 (1995) 57–64. 3. Michael Blackwell has studied this phenomenon using a socio-psychological methodology. See Michael Blackwell, Clinging to Grandeur: British Attitudes and Foreign Policy in the Aftermath of the Second World War, (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1993). 4. Tarling, p. 170. 5. Darby, p. 327. 6. See John Garnett, ‘Defence Policy-Making,’ in John Baylis et al. (eds), Contemporary Strategy, Vol. II: The Nuclear Powers, 2nd edn (London: Croom Helm, 1987) pp. 1–27. 7. Richard Rosecrance, Defense of the Realm: British Strategy in the Nuclear Epoch (New York: Columbia University Press, 1968), Appendix Table 1, Defense Expenditures, pp. -

JFQ 11 ▼JFQ FORUM Become Customer-Oriented Purveyors of Narrow NOTES Capabilities Rather Than Combat-Oriented Or- 1 Ganizations with a Broad Focus and an Under- U.S

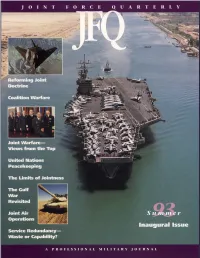

Warfare today is a thing of swift movement—of rapid concentrations. It requires the building up of enormous fire power against successive objectives with breathtaking speed. It is not a game for the unimaginative plodder. ...the truly great leader overcomes all difficulties, and campaigns and battles are nothing but a long series of difficulties to be overcome. — General George C. Marshall Fort Benning, Georgia September 18, 1941 Inaugural Issue JFQ CONTENTS A Word from the Chairman 4 by Colin L. Powell Introducing the Inaugural Issue 6 by the Editor-in-Chief JFQ FORUM JFQ Inaugural Issue The Services and Joint Warfare: 7 Four Views from the Top Projecting Strategic Land Combat Power 8 by Gordon R. Sullivan The Wave of the Future 13 by Frank B. Kelso II Complementary Capabilities from the Sea 17 by Carl E. Mundy, Jr. Ideas Count by Merrill A. McPeak JOINT FORCE QUARTERLY 22 JFQ Reforming Joint Doctrine Coalition Warfare What’s Ahead for the Armed Forces? by David E. Jeremiah Joint Warfare— Views from the Top 25 United Nations Peacekeeping The Limits of Jointness The Gulf War Service Redundancy: Waste or Hidden Capability? Revisited Joint Air Summer Operations 93 by Stephen Peter Rosen Inaugural Issue 36 Service Redundancy— Waste or Capability? A PROFESSIONAL MILITARY JOURNAL ABOUT THE COVER Reforming Joint Doctrine The cover shows USS Dwight D. Eisenhower, 40 by Robert A. Doughty passing through the Suez Canal during Opera- tion Desert Shield, a U.S. Navy photo by Frank A. Marquart. Photo credits for insets, from top United Nations Peacekeeping: Ends versus Means to bottom, are Schulzinger and Lombard (for 48 by William H. -

Albert C. Wedemeyer Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf3x0n99pv No online items Register of the Albert C. Wedemeyer papers Finding aid prepared by Rebecca J. Mead Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 1998 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Albert C. 83007 1 Wedemeyer papers Title: Albert C. Wedemeyer papers Date (inclusive): 1897-1988 Collection Number: 83007 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 149 manuscript boxes, 1 card file box, 14 oversize boxes, 1 oversize folder, 2 motion picture film reels, 19 sound discs, 1 sound cassette, 2 maps, memorabilia(87.2 Linear Feet) Abstract: Orders, plans, memoranda, reports, correspondence, speeches and writings, clippings, printed matter, photographs, and memorabilia relating to Allied strategic planning during World War II, military operations in China, American foreign policy in China, and post-war American politics and foreign relations. Creator: Wedemeyer, Albert C. (Albert Coady), 1896-1989 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Materials were acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1983, with increments received in later years. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Albert C. Wedemeyer papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. 1896 July 9 Born, Omaha, Nebraska 1918 Commissioned Second Lieutenant, U. S. Army 1919 Graduated from United States Military Academy, West Point, New York 1919-1922 Assigned to Infantry School and 29th Infantry, Fort Benning, Georgia 1920 Promoted to First Lieutenant 1922-1923 Aide-de-Camp to Brigadier General Paul B.