Re·Bus: Issue 9 Spring 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ieonography of Sanctuary Doors from Patmos and Its Place in The

The Ieonography of Sanctuary Doors from Patmos and its Place in the Iconographie program of the Byzantine Ieonostasis By Georgios Kellaris A thesls sutmitted to the Facu1ty of Graduate Studies { and Research in partial fulfi1lment of the requirernents for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Art history McGill University March, 1991 © Georgios Kellaris 1991 Montréal, Québec, canada ---------~~- - ---- il The lconostasis is the most characteristic feature of the Orthodox Church. The metaphyslcal conception of the space of the church prQnpted its emergence, and the ~tical Interpretation of the Liturgy deter~ned its evolution. These aspects were reflected in the iconographie program of the iconostasis. The sanctuary dOOIS are the only part of tt.e Patmlan iconostases bearing figurative decoIatlon. The study of the themes on the doors reveals an iconographie program with strong lituIglcal character. Furthermore, this program encompasses the entire range of the ~tical syrrbol1sm pertaining to the iconostasis. The anal}JSis indicates that the doors are instrumental in the function of the iconostasis as a liturgical device aim1ng at a greater unitY between the earthly and the divine realms. ill 1 L t iconostase est un élément Indispe... .Able de l'Église OrthodoAe. La raison de sa naissance se trouve dans la conception métaphysique de l'éspace ecclésiastique et sa évolution a été determlné par l'interprétë.\tion mystique de la 11 turgie. Ces aspects sont reflétés par le progranme iconographique de l'iconostase. Dctns les iconostases de PatIOOs la porte est la seule section où se trouve des décorations figuratives. L'étude de thémes trouvé sur ces portes révéle un programne iconographique de caractère liturgique. -

Icone Di Roma E Del Lazio 1

Icone di Roma e del Lazio 1 Icone di Roma Giorgio Leone Icone di Roma e del Lazio 1 Giorgio Leone Repertori dell’Arte del Lazio - 5/6 G. LEONE ICONE DI ROMA E DEL LAZIO ISBN 978-88-8265-731-4 Museo Soprintendenza per i Beni Storici, Artistici In copertina: Diffuso ed Etnoantropologici del Lazio Direzione Regionale per i Beni Culturali Madonna Advocata detta Madonna di San Sisto, tavola, cm 71.5 x 42.5, Chiesa del Rosario Lazio e Paesaggistici del Lazio a Monte Mario, Roma, particolare «L’ERMA» «L’ERMA» di BRETSCHNEIDER Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali Soprintendenza per i Beni Storici, Artistici ed Etnoantropologici del Lazio (Repertori, 5-6) Giorgio Leone Icone di Roma e del Lazio I TOMO «L’ERMA» di BRETSCHNEIDER GIORGIO LEONE Icone di Roma e del Lazio Repertori dell'Arte del Lazio 5-6 Soprintendenza per i Beni Storici, «L’ERMA» di BRETSCHNEIDER Artistici ed Etnoantropologici del Lazio Direzione editoriale Progetto scientifico e Roberto Marcucci direzione della collana Soprintendente ANNA IMPONENTE Redazione ROSSELLA VODRET Elena Montani Segreteria del Soprintendente Daniele Maras Laura Ceccarelli Dario Scianetti Direzione scientifica Rosalia Pagliarani Maurizio Pinto ANNA IMPONENTE con la collaborazione di Giorgia Corrado Rossella Corcione Coordinamento scientifico Archivio Fotografico Elaborazione immagini e impaginazione integrata GIORGIO LEONE Graziella Frezza, responsabile Soprintendenza Speciale per il Alessandra Montedoro Dario Scianetti Claudio Fabbri Maurizio Pinto Patrimonio Storico, Artistico ed Rossella Corcione -

The Madre Della Consolazione Icon in the British Museum: Post-Byzantine Painting, Painters and Society on Crete*

JAHRBUCH DER ÖSTERREICHISCHEN BYZANTINISTIK, 53. Band/2003, 239–255 © 2003 by Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien ANGELIKI LYMBEROPOULOU / BIRMINGHAM THE MADRE DELLA CONSOLAZIONE ICON IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM: POST-BYZANTINE PAINTING, PAINTERS AND SOCIETY ON CRETE* With two plates A small portable icon (350 × 270 mm), now in the British Museum, Department of Medieval and Later Antiquities (reg. No. 1994, 1–2, 6), depicts the Virgin and Child (fig. 1). It is painted on a single panel of pine wood, apparently without fabric between the ground and wood support. The icon was bequeathed by Guy Holford Dixon JP, who bought it from the Temple Gallery. A label on the back, attached when the icon was in the possession of the Temple Gallery, describes it as being Russian of the six- teenth century. In a preliminary Museum catalogue, however, the origin was given as Italy or Crete and the date as seventeenth century.1 The truth about the origin and the dating of the icon, as we shall see, lies in the mid- dle: I will argue that it is from Crete and of the sixteenth century. The Virgin is depicted half-length, holding the Christ-Child in her right arm while touching His left leg gently with her left hand. Her head is tilted towards the Child, although she does not look at Him. She wears a green garment and a purple maphorion on top, which bears pseudo-kufic decoration on the edges; decorative motives are also visible on the gar- ment’s collar and left sleeve. The maphorion is held together in front of the Virgin’s chest with a golden brooch, which apparently used to have decora- tion, now lost. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

Webfile121848.Pdf

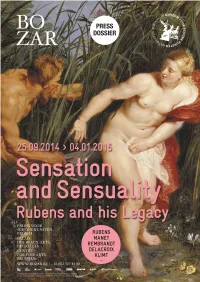

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

The Ieonography of Sanctuary Doors from Patmos and Its Place In

The Ieonography of Sanctuary Doors from Patmos and its Place in the Iconographie program of the Byzantine Ieonostasis By Georgios Kellaris A thesls sutmitted to the Facu1ty of Graduate Studies { and Research in partial fulfi1lment of the requirernents for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Art history McGill University March, 1991 © Georgios Kellaris 1991 Montréal, Québec, canada ---------~~- - ---- il The lconostasis is the most characteristic feature of the Orthodox Church. The metaphyslcal conception of the space of the church prQnpted its emergence, and the ~tical Interpretation of the Liturgy deter~ned its evolution. These aspects were reflected in the iconographie program of the iconostasis. The sanctuary dOOIS are the only part of tt.e Patmlan iconostases bearing figurative decoIatlon. The study of the themes on the doors reveals an iconographie program with strong lituIglcal character. Furthermore, this program encompasses the entire range of the ~tical syrrbol1sm pertaining to the iconostasis. The anal}JSis indicates that the doors are instrumental in the function of the iconostasis as a liturgical device aim1ng at a greater unitY between the earthly and the divine realms. ill 1 L t iconostase est un élément Indispe... .Able de l'Église OrthodoAe. La raison de sa naissance se trouve dans la conception métaphysique de l'éspace ecclésiastique et sa évolution a été determlné par l'interprétë.\tion mystique de la 11 turgie. Ces aspects sont reflétés par le progranme iconographique de l'iconostase. Dctns les iconostases de PatIOOs la porte est la seule section où se trouve des décorations figuratives. L'étude de thémes trouvé sur ces portes révéle un programne iconographique de caractère liturgique. -

'Wie Das Zeichnen Wol Zu Begreiffen Sey?'1 The

© Nina Stainer ‘Wie das Zeichnen wol zu begreiffen sey?’1 The Role of Sculptors’ Drawings in the Seventeenth Century Nina Stainer Abstract The early modern sculptor’s education north of the Alps has yet to be thoroughly explored. Three collections of sculptor’s drawings, originating from the Bavarian workshop of Thomas Schwanthaler (1634-1707), found in different locations across central Europe, allow insights into their importance to the early modern sculptor. Use and collection of drawings had mainly practical purposes for instruction and communication inside the workshop. However, inscriptions suggest that sketches were also crafted for personal reasons. The drawings crossed borders not only physically—being taken along on the itinerant craftsmen’s journeys—but also in their functions as media of both professional purpose and personal memorabilia. The article explores the use of drawings in a non-academic environment, presenting examples from the collections. Keywords: Early modern sculpture, Mobility of Early Modern artists, Sculptor’s drawings. ***** In the first part of his extensive historical work, the Teutsche Academie, published first in 1675, the German painter and art writer Joachim von Sandrart included a chapter discussing the re•bus Issue 9 Spring 2020 3 © Nina Stainer meaning of drawing for the arts of painting and sculpture. Describing the best ways to acquire drawing skills he states that many sculptors lack practice in sketching on paper and therefore prefer to produce small-scale models from clay or wax.2 Scholarship -

Digital Version for Tablet and Desktop (Pdf)

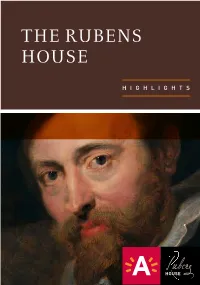

THE RUBENS HOUSE HIGHLIGHTS THE RUBENS HOUSE HIGHLIGHTS 1 THE HOUSE In 1610 Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) and his first wife Isabella Brant (1591–1626) bought a house and a piece of land in Antwerp. In the years that followed, the artist had the building enlarged after his own design, adding a covered, semi-circular statue gallery, a studio, a portico in the style of a triumphal arch, and a garden pavilion. The improvements gave his home the air of an Italian palazzo and embodied Rubens’s artistic ideals: the art of Roman Antiquity and the Italian Renaissance. He also assembled an internationally admired collection of paintings and classical sculpture at the house. Rubens lived and worked here until his death in 1640. The building is believed to have retained its original appearance until the mid-seventeenth century, at which point it was fundamentally altered. Nowadays, the portico My dear friend Rubens, and garden pavilion are the only more or less intact Would you be so good as to admit the bearer of this survivals of the seventeenth-century complex. letter to the wonders of your home: your paintings, the marble sculptures, and the other works of art in your house and studio? It will be a great delight for him. Your dear friend Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc Aix-en-Provence, 16 August 1626 2 3 1 2 Jacob Harrewijn (c. 1640–after 1732) Frans Duquesnoy (1594–1643) The Rubens House in Antwerp, The Sleeping Silenus 1684, 1692 Gilded bronze and lapis lazuli Engravings (facsimiles) This relief illustrates a story told by the Roman poet These two prints are the earliest known ‘portraits’ Virgil (70 BC–19 AD). -

Bulletin )Berlin College Fall 1972

ILLEN MEMORIAL ART MUSEUM BULLETIN )BERLIN COLLEGE FALL 1972 , ( ALLEN MEMORIAL ART MUSEUM BULLETIN VOLUME XXX, NUMBER 1 FALL 1972 Contents Pompeo Batoni's Portrait of John Wodehouse by Anthony M. Clark ----- 2 The Dating of Creto-Venetian Icons: A Reconsideration in Light of New Evidence by Thalia Gouma Peterson - 12 A Sheet of Figure Studies at Oberlin and Other Drawings by Daniele da Volterra by Paul Barolsky ----- 22 Notes Oberlin-Ashland Archaeological Society 37 Baldwin Lecture Series 1972-73 37 Loans to Museums and Institutions 37 Exhibitions 1972-73 40 Friends of Art Film Series - - - - 41 Friends of Art Concert Series 41 Friends of the Museum ----- 42 Published three times a year by the Allen Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio. $6.00 a year, this issue $2.00; mailed free to members of the Oberlin Friends of Art. Printed by the Press of the Times, Oberlin, Ohio. 1. Pompeo Batoni, John Wodehouse Oberlin Pompeo Batoni's Portrait of John Wodehouse In March, 1761, Giovanni Battista Tiepolo wrote Count Algarotti regarding sketches of his for a commission for S. Marco in Rome: 'You then do me the pleasure of sending me the news of Batoni's indulgence about the small sketches. ."' One wonders what Raphael Mengs, just finishing his Villa Albani ceiling, thought of Tiepolo's sketches. Three decades younger than Tiepolo, Mengs was now a famous painter whose opinion would have carried weight. Both Batoni (1708-1787) and Mengs were favored by the new Venetian pope, Clement XIII (whom they painted in 1760 and 1758 respectively), and by this pope's dis tinguished family; also, both artists at least indirectly can be connected with the Venetian church in Rome, S. -

Collected Coral and the Study of Petrified Luxury in Early Modern Antwerp

Dutch Crossing Journal of Low Countries Studies ISSN: 0309-6564 (Print) 1759-7854 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ydtc20 ‘Unusual Excrescences of Nature’: Collected Coral and the Study of Petrified Luxury in Early Modern Antwerp Marlise Rijks To cite this article: Marlise Rijks (2019) ‘Unusual Excrescences of Nature’: Collected Coral and the Study of Petrified Luxury in Early Modern Antwerp, Dutch Crossing, 43:2, 127-156, DOI: 10.1080/03096564.2017.1299931 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03096564.2017.1299931 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 15 Mar 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1005 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ydtc20 DUTCH CROSSING 2019, VOL. 43, NO. 2, 127–156 https://doi.org/10.1080/03096564.2017.1299931 ‘Unusual Excrescences of Nature’: Collected Coral and the Study of Petrified Luxury in Early Modern Antwerp Marlise Rijks Centre for the Arts in Society (LUCAS), Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Many seventeenth-century Antwerp collections contained coral, coral; collections; Antwerp; both natural and crafted. Also, coral was a pictorial motif depicted petrifaction; 17th century by Antwerp artists on mythological scenes, still lifes, gallery pic- tures, and allegories. Coral was many things at the same time: a commodity crafted into jewellery and objets d’art, a popular collectable in its natural shape, a motif for Antwerp painters, an essential commodity in the European-Indian trade network, a naturalia associated with classical mythology as well as with the Blood of Christ, and a problematic naturalia that raised ques- tions about classification, origins and natural processes. -

Of the National Gallery in Prague

BULLETIN OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY IN PRAGUE XVIII–XIX / 2008–2009 The Bulletin is published by the National Gallery in Prague, Staroměstské náměstí 12, 110 15 Praha 1 (tel./fax: +420-224 301 302/235, e-mail: [email protected]). Please address all correspondence to the Editor-in-Chief at the same address. The Bulletin (ISSN 0862-8912, ISBN 978-80-7035-437-7) invites unsolicited articles in major languages. Articles appearing in the Bulletin are indexed in the BHA. Editor-in-Chief: Vít Vlnas Editors: Lenka Zapletalová Editorial Board: Naděžda Blažíčková-Horová (National Gallery in Prague), Anna Janištinová (National Gallery in Prague), Lubomír Konečný (Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic in Prague), Roman Prahl (Charles University in Prague), Anna Rollová (National Gallery in Prague), Filip Suchomel (National Gallery in Prague), Tomáš Vlček (National Gallery in Prague) Design and graphic layout: Lenka Blažejová Printing: Tisk Horák a. s., Ústí nad Labem We would like to thank the Society of Friends of the National Gallery in Prague for the financial support of this issue. © National Gallery in Prague, 2009 BULLETIN NÁRODNÍ GALERIE V PRAZE XVIII–XIX / 2008–2009 Bulletin vydává Národní galerie v Praze, Staroměstské náměstí 12, 110 15 Praha 1 (tel./fax: +420-224 301 302/235, e-mail: [email protected]). Korespondenci adresujte, prosím, šéfredaktorovi na tutéž adresu. Bulletin (ISSN 0862-8912, ISBN 978-80-7035-437-7) uveřejňuje příspěvky ve světových jazycích a v češtině. Články vycházející v Bulletinu jsou indexovány bibliografií BHA. Šéfredaktor: Vít Vlnas Redakce: Lenka Zapletalová Redakční rada: Naděžda Blažíčková-Horová (Národní galerie v Praze), Anna Janištinová (Národní galerie v Praze), Lubomír Konečný (Akademie věd České republiky v Praze), Roman Prahl (Univerzita Karlova v Praze), Anna Rollová (Národní galerie v Praze), Filip Suchomel (Národní galerie v Praze), Tomáš Vlček (Národní galerie v Praze) Grafická úprav a sazba: Lenka Blažejová Tisk: Tisk Horák a. -

Rubenianum Fund

2021 The Rubenianum Quarterly 1 From limbo to Venice, then to London and the Rubenshuis Towards new premises A highlight of the 2019 Word is out: in March, plans for a new building for exhibition at the Palazzo the Rubens House and the Rubenianum, designed by Ducale in Venice (‘From Titian Robbrecht & Daem architecten and located at Hopland 13, to Rubens. Masterpieces from were presented to the world. The building will serve as Flemish Collections’), this visitor entrance to the entire site, and accommodate visitor ravishing Portrait of a Lady facilities such as a bookshop, a café and an experience Holding a Chain is arguably centre. The present absence of such facilities had led to an one of the most exciting initial funding by Visit Flanders, which, in turn, incited the Rubens discoveries of the City of Antwerp to address all infrastructural needs on site. past decade and perhaps the These include several structural challenges that the finest portrait by the artist Rubenianum has faced for decades, such as the need for remaining in private hands. climate-controlled storage for the expanding research The picture is datable to collections. The new building will have state-of-the-art the beginning of Rubens’s storage rooms on four levels, as well as two library career, and was probably floors with study places, in a light and energy-efficient painted either during his architecture. The public reading room on the second floor will be accessible to all visitors via an eye-catching spiral short trip from Mantua to staircase, and will bring the Rubenianum collections Spain (between April 1603 within (visual and physical) reach of all, after their and January 1604), or not somewhat hidden life behind the garden wall.