'Wie Das Zeichnen Wol Zu Begreiffen Sey?'1 The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

Webfile121848.Pdf

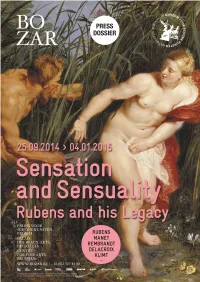

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: TEACHING the EMPIRE: EDUCATION and STATE LOYALTY in LATE HABSBURG AUSTRIA Scott Olen Moore, D

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: TEACHING THE EMPIRE: EDUCATION AND STATE LOYALTY IN LATE HABSBURG AUSTRIA Scott Olen Moore, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Professor Marsha L. Rozenblit Department of History This dissertation examines how Austria utilized its system of public education to develop loyalty to the multinational Habsburg Monarchy from 1867-1918. It draws from a range of sources, including textbooks, pedagogical journals, curricula, school chronicles, school year-end-reports, school inspection reports, and other records related to school administration to show that Austria developed a strong system of civic education which attempted to build a supranational, Austrian identity among its citizens. Its first chapter provides an overview of the Austrian educational system from the eighteenth century to 1914. It also discusses the development of the history curriculum in these schools and illustrates that it possessed a unique ability to serve as a conduit for civic education. The second chapter examines how textbooks and history classes presented Habsburg rulers in a way that portrayed the dynasty as the embodiment of good governance. It shows that such presentations sought to create an interpretation of the Habsburg past that served future rulers while teaching about Austria’s history. This chapter is followed by an analysis of how these textbooks and classes used the Monarchy’s history to support a supranational, Austrian identity in which its citizens were bound by common struggle and a shared past. Most importantly, this chapter shows that officials sought to create this identity in a way that supported existing local and national identities. The fourth chapter explores how school celebrations and patriotic events reinforced civic education efforts. -

Gemeindeblatt Penzing

AUGUST 2021 | NR. 100 Gemeindeblatt Penzing EPFENHAUSEN OBERBERGEN PENZING RAMSACH UNTERMÜHLHAUSEN Nr. 93 Nr. 83 Juni 2020 Nr. 82 Oktober 2018 August 2018 Nr. 67 Gemeindeblatt Penzing Februar 2016 Gemeindeblatt Penzing MIT DEN ORTSTEILEN Gemeindeblatt Penzing UNTER- MIT DEN ORTSTEILEN RAMSACH MÜHLHAUSEN Gemeindeblatt Penzing OBERBERGEN UNTER- PENZING EPFENHAUSEN MIT DEN ORTSTEILEN RAMSACH MÜHLHAUSEN OBERBERGEN UNTER- PENZING EPFENHAUSEN MIT DEN ORTSTEILEN RAMSACH MÜHLHAUSEN OBERBERGEN UNTER- PENZING EPFENHAUSEN MÜHLHAUSEN OBERBERGEN RAMSACH PENZING EPFENHAUSEN See-renade am Baggersee Foto: Doris Mühlberger, Musikverein Penzing e. V. Juni 2021 | Nr. 99 Nr. 96 April 2021 | Nr. 98 Gemeindeblatt Penzing Nr. 95 Dezember 2020 Februar 2021 | Nr. 97 Gemeindeblatt Penzing Nr. 94 Oktober 2020 Gemeindeblatt Penzing August 2020 Gemeindeblatt Penzing EPFENHAUSEN Gemeindeblatt Penzing PENZING OBERBERGEN MIT DEN ORTSTEILEN PENZING Gemeindeblatt Penzing UNTER- EPFENHAUSEN PENZING MIT DEN ORTSTEILEN RAMSACH MÜHLHAUSEN OBERBERGEN EPFENHAUSEN OBERBERGEN UNTER- PENZING EPFENHAUSEN RAMSACH MIT DEN ORTSTEILEN RAMSACH MÜHLHAUSEN OBERBERGEN UNTER- PENZING EPFENHAUSEN OBERBERGEN RAMSACH MÜHLHAUSEN UNTERMÜHLHAUSEN OBERBERGEN RAMSACH PENZING EPFENHAUSEN RAMSACH UNTERMÜHLHAUSEN UNTERMÜHLHAUSEN Entwurf Eheschließung im individuellen Stil … (Trau-Premiere Bürgermeister Hammer im Juni) Das neue Spielgerät für den Spielplatz Penzing Fotos: T. Schmid Standesbeamtin Sylvia Kresin (im Juli) Gemeindeblatt Penzing | | August 2021 3 Liebe Mitbürgerinnen & liebe Mitbürger, Liebe Mitbänke & liebe Mitbänkinnen, „Public viewing“ kenn ich – das mach ich ja quasi rund um die Uhr. Unter „Motto-Party“ kann ich mir auch noch was vorstellen, das ist so ähnlich wie wenn alle wieder festlich weiß oder Krawatte zum Termin im Rathaus tragen, ABER was bitte soll denn dieses „BeerPong“ sein? „Eine coole Sache“. Das könne man im Prinzip überall, am besten aber – so sagen es Simon und der Schnappi – im Jugendhouse in Penzing spielen. -

Chaucer Live Entertainment, Sport, Military, Space Autograph Auction

CHAUCER LIVE ENTERTAINMENT, SPORT, MILITARY, SPACE AUTOGRAPH AUCTION Friday 11th October starting at 5pm PLEASE NOTE NEW START TIME We are accepting commission bids to place on your behalf, email, post or you can register and place bids online. We sell at about 120/150 lots per hour and pause for 15 mins every 250 – 300 lots. Scanned images available online or call and we can post or email them to you. There is a 15% + VAT buyer premium on the hammer price on all lots won. If you bid live online there may be an additional fee of 3%. The sale will be held live at www.Invaluable.com online. Just follow the link from the website www.chaucercovers.com to see all the lots. COLLECTIONS LOT001 - RAF Collection 75th ann. covers, three flown by the RAF each with three aircraft illustrated, flown by the RAF with flight cachets. VIP signed by Grp Capt Devas AFC DFC, AVM S Dick AFC, AVM J Allison. Good condition Est. £10 - 15 LOT002 - England Football signed collection of five 10 x 8 colour photo in England strip signed by Ian Walker, Sol Campbell, Tim Sherwood, Darren Anderton, Teddy Sherringham. Good condition Est. £10 - 15 LOT003 - Russian Space Airmails about 20 plus stunning 10 x 8 colour Juri Gagarin montage photo. Good condition Est. £5 - 10 LOT004 - Vintage Cigarette Cards four albums complete with all cards, W D & H O Wills The Sea Shore & Wild Flowers. John Players British Freshwater Fishes & Sea Fishes. A few fox marks to fronts but cards look fine. -

Digital Version for Tablet and Desktop (Pdf)

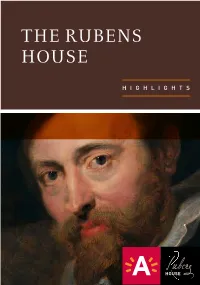

THE RUBENS HOUSE HIGHLIGHTS THE RUBENS HOUSE HIGHLIGHTS 1 THE HOUSE In 1610 Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) and his first wife Isabella Brant (1591–1626) bought a house and a piece of land in Antwerp. In the years that followed, the artist had the building enlarged after his own design, adding a covered, semi-circular statue gallery, a studio, a portico in the style of a triumphal arch, and a garden pavilion. The improvements gave his home the air of an Italian palazzo and embodied Rubens’s artistic ideals: the art of Roman Antiquity and the Italian Renaissance. He also assembled an internationally admired collection of paintings and classical sculpture at the house. Rubens lived and worked here until his death in 1640. The building is believed to have retained its original appearance until the mid-seventeenth century, at which point it was fundamentally altered. Nowadays, the portico My dear friend Rubens, and garden pavilion are the only more or less intact Would you be so good as to admit the bearer of this survivals of the seventeenth-century complex. letter to the wonders of your home: your paintings, the marble sculptures, and the other works of art in your house and studio? It will be a great delight for him. Your dear friend Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc Aix-en-Provence, 16 August 1626 2 3 1 2 Jacob Harrewijn (c. 1640–after 1732) Frans Duquesnoy (1594–1643) The Rubens House in Antwerp, The Sleeping Silenus 1684, 1692 Gilded bronze and lapis lazuli Engravings (facsimiles) This relief illustrates a story told by the Roman poet These two prints are the earliest known ‘portraits’ Virgil (70 BC–19 AD). -

Dokumentation Chronik Mai 1998-Juni 19991

Dokumentation Chronik Mai 1998-Juni 19991 1998 1.5. Ein Untersuchungsverfahren wird gegen den früheren sozialistischen Außenmi• nister Roland Dumas wegen Beihilfe zur Veruntreuung öffentlicher Mittel in der Schmiergeldaffare des staatlichen Erdölkonzerns Elf Aquitaine eingeleitet. Dumas weist alle Vorwürfe zurück und weigert sich, von seinem Amt als Präsi• dent des Verfassungsrates (Conseil constitutionnel) zurückzutreten. 5.5. In Noumea unterzeichnet Premierminister Lionel Jospin offiziell das Abkom men über das neue Statut Neukaledoniens für die nächsten 15 Jahre. 5.-6.5. Beim 71. deutsch-französischen Gipfel treffen Bundeskanzler Helmut Kohl, Staatspräsident Chirac und Premierminister Jospin in Avignon (Vauc1use) zu sammen. Erstmals findet vor der Gipfelbegegnung eine gemeinsame Konferenz der deutschen und französischen Botschafter aus Bonn, Paris, Brüssel und Wa shington statt, die über die Beziehungen Europas zu Amerika beraten. Im Mit telpunkt des Gipfels stehen die Reform der europäischen Institutionen, Pläne für Beschäftigung und Wachstum sowie die Beratungen über die Entwicklung im Kosovo und im Nahen Osten. In einem gemeinsamen Brief an EU Ratspräsident Tony Blair schlagen Kohl und Chirac vor, insbesondere über die Bedeutung des Subsidiaritätsprinzips nachzudenken. An dem Gipfeltreffen nehmen auch die Justizminister der beiden Länder, Guigou und Schmidt-Jortzig teil, um Fragen deutsch-französischer Ehe- und Kindschaftsrechtskonflikte zu erörtern. 13.5. In einem Bericht an den Premierminister werden technische Sicherheitsmängel -

The Hans Rossbach Aces Collection This Is Quite an Incredible Set of Covers with Over 270 Signature of Top Luftwaffe VIP’S

THE CENTENARY OF THE ROYAL The Hans Rossbach Aces Collection This is quite an incredible set of covers with over 270 signature of top Luftwaffe VIP’s. It took Hans over three years to assemble back in the 1970’s. He AIR FORCE personally visited all aces including great names like Willy Messerschmitt, Werner Von Braun, Herman Obarth, Albert Speer, Erich Hartmann, Adolf August 2018 Galland, Gerd Barkhorn plus many more. There is even a cover signed by Issue 4 five members of Richthofen’s original flying circus. Many of the individual covers are now worth well over £200 with the Von Braun and Messerschmitt now worth £1500. Other rare signatures include Rudel Batz, Hanna Reichi, Hans Bauhr (Hitlerís pilot), Matoni, Skorzaney, Kurt Tank. Hans only did 100 sets of all 80 covers. Each cover has a biography of the signatures printed on the cover, plus numerous b/w photos inside. He originally stated that there are only 20 or so complete sets anywhere in the world. You can’t imagine how much time and effort went in to getting the photos that are inside the covers, the travelling, overprinting of envelopes etc. Each can be identified by a number in a red circle on the reverse, we list here what we have available at this point, but there are still lots of gaps to fill and will keep trying HRA06 £150 £50 per month HRA02 £100 £50 per month over 2 months over 3 months 1971 RAF Fylingdales cover, signed by Ludwig Meister, Josef 1986 Biggin Hill Kraft, Hans Joachim Jabs and Hans Martin Madeball. -

Collected Coral and the Study of Petrified Luxury in Early Modern Antwerp

Dutch Crossing Journal of Low Countries Studies ISSN: 0309-6564 (Print) 1759-7854 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ydtc20 ‘Unusual Excrescences of Nature’: Collected Coral and the Study of Petrified Luxury in Early Modern Antwerp Marlise Rijks To cite this article: Marlise Rijks (2019) ‘Unusual Excrescences of Nature’: Collected Coral and the Study of Petrified Luxury in Early Modern Antwerp, Dutch Crossing, 43:2, 127-156, DOI: 10.1080/03096564.2017.1299931 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03096564.2017.1299931 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 15 Mar 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1005 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ydtc20 DUTCH CROSSING 2019, VOL. 43, NO. 2, 127–156 https://doi.org/10.1080/03096564.2017.1299931 ‘Unusual Excrescences of Nature’: Collected Coral and the Study of Petrified Luxury in Early Modern Antwerp Marlise Rijks Centre for the Arts in Society (LUCAS), Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Many seventeenth-century Antwerp collections contained coral, coral; collections; Antwerp; both natural and crafted. Also, coral was a pictorial motif depicted petrifaction; 17th century by Antwerp artists on mythological scenes, still lifes, gallery pic- tures, and allegories. Coral was many things at the same time: a commodity crafted into jewellery and objets d’art, a popular collectable in its natural shape, a motif for Antwerp painters, an essential commodity in the European-Indian trade network, a naturalia associated with classical mythology as well as with the Blood of Christ, and a problematic naturalia that raised ques- tions about classification, origins and natural processes. -

Die Stadt Salzburg 1938

Die Stadt Salzburg im Jahr 1938 Zeitungsdokumentation von S. Göllner Die Stadt Salzburg 1938 Zeitungsdokumentation zusammengestellt von Siegfried Göllner Berücksichtigte Tageszeitungen: Salzburger Chronik: SC (ab 12. März: SZ) Salzburger Volksblatt: SVB Salzburger Zeitung: SZ (mit 13. 8. 1938 eingestellt) 1 Die Stadt Salzburg im Jahr 1938 Zeitungsdokumentation von S. Göllner Statistiken und Jahresberichte 1937 1937 Hochzeiten und Geburten in Österreich. Statistiken über Heiratsalter in Österreich und die Geburtenentwicklung 1871-1936. SVB, 26.1.1938, S. 9. 1937 Kirchenübertritte. Der evangelische Oberkirchenrat veröffentlicht die Kirchenstatistik für 1937. Demnach sind 7.464 Personen zur evangelischen Kirche übergetreten, davon 5.467 Katholiken und 1.997 Konfessionslose. 1.339 Personen sind aus der ev. Kirche ausgetreten. Ihre Höchstzahl hatten die Übertritte im Jahr 1934 mit 25.140, seither waren es jährlich um die 8.000. Wien und die Steiermark verzeichneten die höchsten Übertrittszahlen. SC, 9.3.1938, S. 5. 1937 Spendeneingang des Deutschen Schulvereines. Der Deutsche Schulverein Südmark vermeldet den Spendeneingang des Jahres 1937. Gerechnet auf die Bevölkerung war das Land Salzburg am Spendenfreudigsten. SVB, 24.3.1938, S. 8. SZ, 24.3.1938, S. 5. 1937 Neuerwerbungen des Museums 1937. Das SVB berichtet über die Neuerwerbungen des Salzburger Museums im Jahr 1937. SVB, 1.12.1938, S. 9f. 1937 Kündigungen bei Union. Die Union-Lebensmittelwerke haben im Zuge der Schließung der Fleischhauerei- und Konservenabteilung und der damit nötigen Verkleinerung der Verwaltung Ende 1937 zwei Vertrauensmänner der Angestellten ohne Befragung des Einigungsamtes gekündigt, wogegen die übrigen Angestellten ebendort Einspruch erhoben haben. Dem Einspruch wurde stattgegeben. SC, 9.3.1938, S. 6f. SVB, 26.1.1938, S. -

Of the National Gallery in Prague

BULLETIN OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY IN PRAGUE XVIII–XIX / 2008–2009 The Bulletin is published by the National Gallery in Prague, Staroměstské náměstí 12, 110 15 Praha 1 (tel./fax: +420-224 301 302/235, e-mail: [email protected]). Please address all correspondence to the Editor-in-Chief at the same address. The Bulletin (ISSN 0862-8912, ISBN 978-80-7035-437-7) invites unsolicited articles in major languages. Articles appearing in the Bulletin are indexed in the BHA. Editor-in-Chief: Vít Vlnas Editors: Lenka Zapletalová Editorial Board: Naděžda Blažíčková-Horová (National Gallery in Prague), Anna Janištinová (National Gallery in Prague), Lubomír Konečný (Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic in Prague), Roman Prahl (Charles University in Prague), Anna Rollová (National Gallery in Prague), Filip Suchomel (National Gallery in Prague), Tomáš Vlček (National Gallery in Prague) Design and graphic layout: Lenka Blažejová Printing: Tisk Horák a. s., Ústí nad Labem We would like to thank the Society of Friends of the National Gallery in Prague for the financial support of this issue. © National Gallery in Prague, 2009 BULLETIN NÁRODNÍ GALERIE V PRAZE XVIII–XIX / 2008–2009 Bulletin vydává Národní galerie v Praze, Staroměstské náměstí 12, 110 15 Praha 1 (tel./fax: +420-224 301 302/235, e-mail: [email protected]). Korespondenci adresujte, prosím, šéfredaktorovi na tutéž adresu. Bulletin (ISSN 0862-8912, ISBN 978-80-7035-437-7) uveřejňuje příspěvky ve světových jazycích a v češtině. Články vycházející v Bulletinu jsou indexovány bibliografií BHA. Šéfredaktor: Vít Vlnas Redakce: Lenka Zapletalová Redakční rada: Naděžda Blažíčková-Horová (Národní galerie v Praze), Anna Janištinová (Národní galerie v Praze), Lubomír Konečný (Akademie věd České republiky v Praze), Roman Prahl (Univerzita Karlova v Praze), Anna Rollová (Národní galerie v Praze), Filip Suchomel (Národní galerie v Praze), Tomáš Vlček (Národní galerie v Praze) Grafická úprav a sazba: Lenka Blažejová Tisk: Tisk Horák a. -

Rubenianum Fund

2021 The Rubenianum Quarterly 1 From limbo to Venice, then to London and the Rubenshuis Towards new premises A highlight of the 2019 Word is out: in March, plans for a new building for exhibition at the Palazzo the Rubens House and the Rubenianum, designed by Ducale in Venice (‘From Titian Robbrecht & Daem architecten and located at Hopland 13, to Rubens. Masterpieces from were presented to the world. The building will serve as Flemish Collections’), this visitor entrance to the entire site, and accommodate visitor ravishing Portrait of a Lady facilities such as a bookshop, a café and an experience Holding a Chain is arguably centre. The present absence of such facilities had led to an one of the most exciting initial funding by Visit Flanders, which, in turn, incited the Rubens discoveries of the City of Antwerp to address all infrastructural needs on site. past decade and perhaps the These include several structural challenges that the finest portrait by the artist Rubenianum has faced for decades, such as the need for remaining in private hands. climate-controlled storage for the expanding research The picture is datable to collections. The new building will have state-of-the-art the beginning of Rubens’s storage rooms on four levels, as well as two library career, and was probably floors with study places, in a light and energy-efficient painted either during his architecture. The public reading room on the second floor will be accessible to all visitors via an eye-catching spiral short trip from Mantua to staircase, and will bring the Rubenianum collections Spain (between April 1603 within (visual and physical) reach of all, after their and January 1604), or not somewhat hidden life behind the garden wall.