Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ministero Per I Beni E Le Attività Culturali E Per Il Turismo Archivio Di Stato Di Genova

http://www.archiviodistatogenova.beniculturali.it Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali e per il turismo Archivio di Stato di Genova Instructiones et relationes Inventario n. 11 Regesti a cura di Elena Capra, Giulia Mercuri, Roberta Scordamaglia Genova, settembre 2020, versione 1.1 - 1 - http://www.archiviodistatogenova.beniculturali.it ISTRUZIONI PER LA RICHIESTA DELLE UNITÀ ARCHIVISTICHE Nella richiesta occorre indicare il nome del fondo archivistico e il numero della busta: quello che nell’inventario è riportato in neretto. Ad esempio per consultare 2707 C, 87 1510 marzo 20 Lettere credenziali a Giovanni Battista Lasagna, inviato in Francia. Tipologia documentaria: Lettere credenziali. Autorità da cui l’atto è emanato: Consiglio degli Anziani. Località o ambito di pertinenza: Francia. Persone menzionate: Giovanni Battista Lasagna. occorre richiedere ARCHIVIO SEGRETO 2707 C SUGGERIMENTI PER LA CITAZIONE DELLE UNITÀ ARCHIVISTICHE Nel citare la documentazione di questo fondo, ferme restando le norme adottate nella sede editoriale di destinazione dello scritto, sarà preferibile indicare la denominazione completa dell’istituto di conservazione e del fondo archivistico seguite dal numero della busta, da quello del documento e, se possibile, dall’intitolazione e dalla data. Ad esempio per citare 2707 C, 87 1510 marzo 20 Lettere credenziali a Giovanni Battista Lasagna, inviato in Francia. Tipologia documentaria: Lettere credenziali. Autorità da cui l’atto è emanato: Consiglio degli Anziani. Località o ambito di pertinenza: Francia. Persone menzionate: Giovanni Battista Lasagna. è bene indicare: Archivio di Stato di Genova, Archivio Segreto, b. 2707 C, doc. 87 «Lettere credenziali a Giovanni Battista Lasagna, inviato in Francia» del 20 marzo 1510. - 2 - http://www.archiviodistatogenova.beniculturali.it SOMMARIO Nota archivistica p. -

Creativity Over Time and Space

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Serafinelli, Michel; Tabellini, Guido Working Paper Creativity over Time and Space IZA Discussion Papers, No. 12644 Provided in Cooperation with: IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Suggested Citation: Serafinelli, Michel; Tabellini, Guido (2019) : Creativity over Time and Space, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 12644, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), Bonn This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/207469 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12644 Creativity over Time and Space Michel Serafinelli Guido Tabellini SEPTEMBER 2019 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12644 Creativity over Time and Space Michel Serafinelli University of Essex, IZA and CReAM Guido Tabellini IGIER, Università Bocconi, CEPR, CESifo and CIFAR SEPTEMBER 2019 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. -

Archivio Segreto, Paesi Diversi in Lettera

http://www.archiviodistatoGenova.beniculturali.it Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali e per il turismo Archivio di Stato di Genova Archivio segreto, Paesi diversi in lettera Regesti dei documenti Inventario n. 32 trascritto a cura di Liliana Piscioneri Genova, gennaio 2021, versione 1.0 - 1 - http://www.archiviodistatoGenova.beniculturali.it ISTRUZIONI P R LA RI"#I STA D LL UNITÀ AR"#I&ISTI"# Nella richiesta occorre indicare il nome del )ondo archivistico, il numero della *usta (che nell’inventario - riportato in corris.ondenza di ciascun regesto, in neretto) e l’identificativo del regesto: Località Data Regesto Numero generale Archivio segreto 25) Albenga 1390 feb. 26 Sentenza emessa nella 341 controversia tra il Comune di Albenga e Villa Salice del Contado di Albenga (copia) occorre richiedere ARCHIVIO SEGRETO, 341, documento di cui al regesto n. 25 SUGGERI3 NTI P R LA CITAZION D LL UNITÀ AR"#I&ISTI"# Per citare la documentazione di 4uesto )ondo, )erme restando le norme adottate nella sede editoriale di destinazione dello scritto, sar5 .re)eribile indicare la denominazione co(.leta dell’istituto di conservazione e del )ondo archivistico, seguite dal numero della *usta e dall’indicazione del fascicolo ri)erito alla singola località. Ad ese(.io, per citare Località Data Regesto Numero generale Archivio segreto 25) Albenga 1390 feb. 26 Sentenza emessa nella 341 controversia tra il Comune di Albenga e Villa Salice del Contado di Albenga (copia) - bene indicare: Archivio di Stato di Genova, Archivio segreto, n. 341, Albenga. - 2 - http://www.archiviodistatoGenova.beniculturali.it Nota archivistica La serie Paesi diversi in lettera, corris.ondente alle unit5 341-370 del )ondo !rchivio segreto, - una delle raccolte diplomatiche che, a .artire da un nucleo di documenti .ro*abilmente già isolato nel corso dell’et5 (oderna, sono state costituite e ordinate, secondo criteri non storici e tipicamente sabaudi, durante la .ermanenza .resso gli !rchivi di "orte a Torino, nella .rima met5 del secolo XIX. -

The Collecting, Dealing and Patronage Practices of Gaspare Roomer

ART AND BUSINESS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NAPLES: THE COLLECTING, DEALING AND PATRONAGE PRACTICES OF GASPARE ROOMER by Chantelle Lepine-Cercone A thesis submitted to the Department of Art History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (November, 2014) Copyright ©Chantelle Lepine-Cercone, 2014 Abstract This thesis examines the cultural influence of the seventeenth-century Flemish merchant Gaspare Roomer, who lived in Naples from 1616 until 1674. Specifically, it explores his art dealing, collecting and patronage activities, which exerted a notable influence on Neapolitan society. Using bank documents, letters, artist biographies and guidebooks, Roomer’s practices as an art dealer are studied and his importance as a major figure in the artistic exchange between Northern and Sourthern Europe is elucidated. His collection is primarily reconstructed using inventories, wills and artist biographies. Through this examination, Roomer emerges as one of Naples’ most prominent collectors of landscapes, still lifes and battle scenes, in addition to being a sophisticated collector of history paintings. The merchant’s relationship to the Spanish viceregal government of Naples is also discussed, as are his contributions to charity. Giving paintings to notable individuals and large donations to religious institutions were another way in which Roomer exacted influence. This study of Roomer’s cultural importance is comprehensive, exploring both Northern and Southern European sources. Through extensive use of primary source material, the full extent of Roomer’s art dealing, collecting and patronage practices are thoroughly examined. ii Acknowledgements I am deeply thankful to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Sebastian Schütze. -

Birth Year Obtained Individually from the Web Table 2: Dalai Lamas and Regents Since 1678

TABLE OF CONTENTS Age of Appointment Time Series (Tables 1A and 1B) Birth year obtained individually from the web Table 2: Dalai Lamas and Regents since 1678 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Politics_in_Tibet Age of Appointment Cross Section http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religion_in_the_United_States Birth year obtained individually from the web, by phone and email Age of Appointment of CEOs http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1227055,00.html Birth year obtained individually from the web Age of Appointment of Doges in Venice http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Doges_of_Venice Birth year obtained individually from the web Age of Appointment of Doges in Genoa http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doge_of_Genoa Birth year obtained individually from the web Age of Appointment of Cardinals The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church - Consistories of the XX Century http://www.fiu.edu/~mirandas/consistories-xx.htm Birth year obtained individually from the web TABLE 1A: REIGN AND AGE AT APPOINTMENT CATHOLIC ANGLICAN EPISCOPAL LUTHERAN M.SYNOD Pope reign age Archbishopreign age Presiding Bishopreign age President reign age Pius VI 1775-1799 63 F. Cornwallis1768-1783 55 W. White 1789-1789 41 Pius VII 1800-1823 57 J. Moore 1783-1805 53 S. Seabury 1789-1792 60 Leo XII 1823-1829 63 C. Manners-Sutton1805-1828 50 S. Provoost 1792-1795 50 Pius VIII 1829-1830 67 W. Howley 1828-1848 62 W. White 1795-1836 39 Gregory XVI 1831-1846 65 J. Sumner 1848-1862 68 A. Griswold 1836-1843 70 Pius IX 1846-1878 54 C. Longley 1862-1868 68 P. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

Webfile121848.Pdf

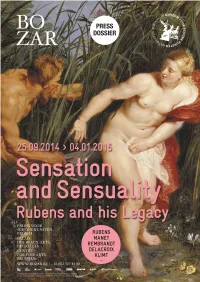

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

Die Beischriften Des Peter Paul Rubens

Die Beischriften des Peter Paul Rubens Überlegungen zu handschriftlichen Vermerken auf Zeichnungen Dissertation zur Erlangung der Würde des Doktors der Philosophie des Fachbereichs Kulturgeschichte und Kulturkunde der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Veronika Kopecky aus Wien Hamburg und London 2008 / 2012 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Martin Warnke 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Charlotte Schoell-Glass Datum der Disputation: 16. April 2008 Tag des Vollzugs der Promotion: 02. Juli 2008 Textband Vorwort 2 Danksagung 6 Einleitung 8 Die Unterschrift 11 Signatur und Fälschung, Zuschreibung und Bewertung 11 Der Adressat der Beischrift I. Die Auftragszeichnung 14 Inschriften und Inschriftenträger 15 Form. Von der Vorgabe zur Zeichnung, von der Zeichnung zum Werk 18 Farb- und Materialangaben, Maße und Gewichte 19 Der Adressat der Beischrift II. Anleitungen für ausführende Künstler 22 Inhalt. Die Erweiterung des Sichtbaren 24 Der Adressat der Beischrift III. Der künstlerische Monolog 25 Identifikation und Titel 26 Ort und Zeit 31 Das Zitat. Inhalt, Interpretation und Stimmung 33 Zusammenhanglose und unleserliche Beischriften 35 Die Beischrift bei Rubens 38 Die Zeichnung in Rubens’ Werkstatt 39 Erudizione ed eloquenza 41 Rubens’ Handschrift 48 Sprachhierarchie und Höflichkeit 49 Die Signatur des Rubens 55 Zuschreibungen 57 Der Adressat der Beischrift I. Die Auftragszeichnung 58 Inschriften 59 Formales bei Rubens. Farbe, Material und Größe 64 Kopien nach der Antike. Vom Antiquarius zum Archäologen 69 Nützliches und Wesentliches. Der Adressat der Beischrift II. Anleitungen und Hinweise 73 Der kürzeste Weg von der Idee zum Werk. Die erläuternde Beischrift 78 Identifikationen 78 Beschreibungen des Inhalts 81 Vorausblick und Auswahlmöglichkeiten 82 Veränderungen und Ergänzungen 86 Das Literaturzitat 93 Offene Fragen. Unleserliche und zusammenhanglose Beischriften 102 Endnoten 107 Vorwort Zeichnen und Malen sind kreative Prozesse, die mit einer Idee beginnen und für deren Ausführung es der Hand bedarf. -

CHG Library Book List

CHG Library Book List (Belgium), M. r. d. a. e. d. h. (1967). Galerie de l'Asie antérieure et de l'Iran anciens [des] Musées royaux d'art et d'histoire, Bruxelles, Musées royaux d'art et dʹhistoire, Parc du Cinquantenaire, 1967. Galerie de l'Asie antérieure et de l'Iran anciens [des] Musées royaux d'art et d'histoire by Musées royaux d'art et d'histoire (Belgium) (1967) (Director), T. P. F. H. (1968). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin: Volume XXVI, Number 5. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art (January, 1968). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin: Volume XXVI, Number 5 by Thomas P.F. Hoving (1968) (Director), T. P. F. H. (1973). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin: Volume XXXI, Number 3. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art (Ed.), A. B. S. (2002). Persephone. U.S.A/ Cambridge, President and Fellows of Harvard College Puritan Press, Inc. (Ed.), A. D. (2005). From Byzantium to Modern Greece: Hellenic Art in Adversity, 1453-1830. /Benaki Museum. Athens, Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation. (Ed.), B. B. R. (2000). Christian VIII: The National Museum: Antiquities, Coins, Medals. Copenhagen, The National Museum of Denmark. (Ed.), J. I. (1999). Interviews with Ali Pacha of Joanina; in the autumn of 1812; with some particulars of Epirus, and the Albanians of the present day (Peter Oluf Brondsted). Athens, The Danish Institute at Athens. (Ed.), K. D. (1988). Antalya Museum. İstanbul, T.C. Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı Döner Sermaye İşletmeleri Merkez Müdürlüğü/ Ankara. (ed.), M. N. B. (Ocak- Nisan 2010). "Arkeoloji ve sanat. (Journal of Archaeology and Art): Ölümünün 100.Yıldönümünde Osman Hamdi Bey ve Kazıları." Arkeoloji Ve Sanat 133. -

Repertorio Di Fonti Sul Patriziato Genovese

Soprintendenza Archivistica per la Liguria Repertorio di fonti sul Patriziato genovese scheda n° 4 compilatore: Andrea Lercari, aggiornata al 21/09/2010 famiglia: Airolo Altre forme del nome: Airoli, de Airolo, Ayrolo, Ayrolus, de Ayrolis, Ayrollo. Albergo: Negrone Titoli: Patrizio genovese, marchese di Rivalta, conte consignore di Sala Famiglie aggregate (solo per le famiglie capo-albergo): Feudi: Rivalta Scrivia; Sala (Monferrato) Arma gentilizia: «D’azzurro alla quercia terrazzata sul terreno di verde, sinistrata da un leone d’oro». Nota storica: Famiglia di origine popolare, tradizionalmente considerata originaria della villa di Godano, in Val di Vara nell’entroterra di Levanto, gli Airolo ebbero ascrizione al patriziato genovese in vari rami, riconducibili a un comune stipite ma sostanzialmente distanti e indipendenti tra loro, i quali con diversa fortuna e in epoche differenti si affermarono nella vita politica, nell’economia e più in generale nella società genovesi. Quali che siano le origini più remote della famiglia, è accertato dal XVI secolo il suo radicamento nella villa di Granarolo, che la tradizione vuole derivare il proprio nome dall’originario toponimo Airolo, da cui Grande Airolo e infine Granarolo, un’area collinare agricola sulle alture di Genova, fuori la porta di San Tomaso, ove sorgevano numerose residenze estive di facoltosi cittadini genovesi e contraddistinta da tre importanti fondazioni ecclesiastiche: la chiesa di Santa Maria (la parrocchiale, nella parte alta), quella di San Rocco (nella parte bassa) e il convento dei Padri di San Francesco da Paola, nella cui chiesa, dedicata a Gesù e Maria, gli Airolo ebbero i propri sepolcri gentilizi. La linea dei primi Airolo ascritti nel 1528 La prima linea della famiglia fu ascritta al Liber Civilitatis sin dal 1528 con Nicolò de Ayrolo, aggregato all’albergo Negrone. -

Spazi Per La Memoria Storica

SPAZI PER LA MEMORIA STORICA ROMA 2009 Genova, Complesso monumentale di Sant’Ignazio: particolare della loggia di Psiche Genova, Palazzetto criminale PUBBLICAZIONI DEGLI ARCHIVI DI STATO SAGGI 93 SPAZI PER LA MEMORIA STORICA La storia di Genova attraverso le vicende delle sedi e dei documenti dell’Archivio di Stato Atti del convegno internazionale Genova, 7 - 10 giugno 2004 a cura di ALFONSO ASSINI e PAOLA CAROLI MINISTERO PER I BENI E LE ATTIVITÀ CULTURALI DIREZIONE GENERALE PER GLI ARCHIVI 2009 DIREZIONE GENERALE PER GLI ARCHIVI Servizio III - Studi e ricerca Direttore generale per gli archivi: Luciano Scala Direttore del Servizio III: Patrizia Ferrara Impaginazione: Fausto Amalberti Autorizzazioni alla pubblicazione delle immagini: Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Roma Archivio di Stato di Venezia Archivio Storico del Comune di Genova Biblioteca Civica Berio, Genova Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense, Milano British Library, Londra Centro di Documentazione per la Storia, l’Arte e l’Immagine di Genova Staatsbibliothek, Berlino © 2009 Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali Direzione generale per gli archivi ISBN 978-88-7125-302-2 Stampato nel mese di novembre 2009 a cura della Tipografia Brigati Glauco & c. s.d.f. – Genova ARCHIVIO DI STATO DI GENOVA Manifestazioni “Genova capitale della cultura 2004” Convegno internazionale Spazi per la memoria storica La storia di Genova attraverso le vicende delle sedi e dei documenti dell’Archivio di Stato Sotto l’Alto Patronato del Presidente della Repubblica Complesso monumentale di Sant’Ignazio, -

Business Relations, Identities, and Political Resources of the Italian

European Review of History Revue européenne d’histoire Volume 23 Number 3 June 2016 CONTENTS—SOMMAIRE DOSSIER: Business Relations, Identities, and Political Resources of the Italian Merchants in the Early-Modern Spanish Monarchy / Relations commerciales, identités et ressources politiques des marchands italiens dans la Monarchie espagnole à l’époque moderne GUEST EDITORS: Catia Brilli and Manuel Herrero Sánchez The business relations, identities and political resources of Italian merchants in the early-modern Spanish monarchy: some introductory remarks Manuel Herrero Sánchez 335 Tuscan merchants in Andalusia: a historiographical debate Angela Orlandi 347 A Genoese merchant and banker in the Kingdom of Naples: Ottavio Serra and his business network in the Spanish polycentric system, c.1590–1620 Yasmina Rocío Ben Yessef Garfia 367 Looking through the mirrors: materiality and intimacy at Domenico Grillo’s mansion in Baroque Madrid Felipe Gaitán Ammann 400 Small but powerful: networking strategies and the trade business of Habsburg-Italian merchants in Cadiz in the second half of the eighteenth century Klemens Kaps 427 Coping with Iberian monopolies: Genoese trade networks and formal institutions in Spain and Portugal during the second half of the eighteenth century Catia Brilli 456 I. ARTICLES—ARTICLES Politics of place: political representation and the culture of electioneering in the Netherlands, c.1848–1980s Harm Kaal 486 A regionalisation or long-distance trade? Transformations and shifts in the role of Tana in the Black Sea trade in