Control Parameters for Musical Instruments: a Foundation for New Mappings of Gesture to Sound

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano by Maria Payan, M.M., B.M. A Thesis In Music Performance Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved Dr. Lisa Garner Santa Chair of Committee Dr. Keith Dye Dr. David Shea Dominick Casadonte Interim Dean of the Graduate School May 2013 Copyright 2013, Maria Payan Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have started without the extraordinary help and encouragement of Dr. Lisa Garner Santa. The education, time, and support she gave me during my studies at Texas Tech University convey her devotion to her job. I have no words to express my gratitude towards her. In addition, this project could not have been finished without the immense help and patience of Dr. Keith Dye. For his generosity in helping me organize and edit this project, I thank him greatly. Finally, I would like to give my dearest gratitude to Donna Hogan. Without her endless advice and editing, this project would not have been at the level it is today. ii Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................. ii LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................. v 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ -

Unit 10.2 the Physics of Music Objectives Notes on a Piano

Unit 10.2 The Physics of Music Teacher: Dr. Van Der Sluys Objectives • The Physics of Music – Strings – Brass and Woodwinds • Tuning - Beats Notes on a Piano Key Note Frquency (Hz) Wavelength (m) 52 C 524 0.637 51 B 494 0.676 50 A# or Bb 466 0.717 49 A 440 0.759 48 G# or Ab 415 0.805 47 G 392 0.852 46 F# or Gb 370 0.903 45 F 349 0.957 44 E 330 1.01 43 D# or Eb 311 1.07 42 D 294 1.14 41 C# or Db 277 1.21 40 C (middle) 262 1.27 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piano_key_frequencies 1 Vibrating Strings - Fundamental and Overtones A vibration in a string can L = 1/2 λ1 produce a standing wave. L = λ Usually a vibrating string 2 produces a sound whose L = 3/2 λ3 frequency in most cases is constant. Therefore, since L = 2 λ4 frequency characterizes the pitch, the sound produced L = 5/2 λ5 is a constant note. Vibrating L = 3 λ strings are the basis of any 6 string instrument like guitar, L = 7/2 λ7 cello, or piano. For the fundamental, λ = 2 L where Vibration, standing waves in a string, L is the length of the string. The fundamental and the first 6 overtones which form a harmonic series http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vibrating_string Length of Piano Strings The highest key on a piano corresponds to a frequency about 150 times that of the lowest key. If the string for the highest note is 5.0 cm long, how long would the string for the lowest note have to be if it had the same mass per unit length and the same tension? If v = fλ, how are the frequencies and length of strings related? Other String Instruments • All string instruments produce sound from one or more vibrating strings, transferred to the air by the body of the instrument (or by a pickup in the case of electronically- amplified instruments). -

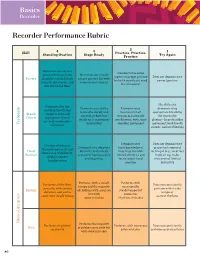

Recorder Performance Rubric

Basics Recorder Recorder Performance Rubric 2 Skill 4 3 Practice, Practice, 1 Standing Ovation Stage Ready Practice Try Again Demonstrates correct Demonstrates some posture with neck and Demonstrates mostly aspects of proper posture Does not demonstrate Posture shoulders relaxed, back proper posture but with but with significant need correct posture straight, chest open, and some inconsistencies for refinement feet flat on the floor Has difficulty Demonstrates low Demonstrates ability Demonstrates demonstrating and deep breath that to breathe deeply and inconsistent air appropriate breathing Breath supports even and control air flow, but stream, occasionally for successful Control appropriate flow of steady air is sometimes overblowing, with some playing—large shoulder air, with no shoulder Technique inconsistent shoulder movement movement, loud breath movement sounds, and overblowing Demonstrates Does not demonstrate Consistently fingers Demonstrates adequate basic knowledge of proper instrumental the notes correctly and Hand dexterity with mostly fingerings but with technique (e.g., incorrect shows ease of dexterity; Position consistent hand position limited dexterity and hand on top, holes displays correct and fingerings inconsistent hand not covered, limited hand position position dexterity) Performs with a steady Performs with Performs all rhythms Does not consistently tempo and the majority occasionally correctly, with correct perform with steady Rhythm of rhythms with accuracy steady tempo but duration, and with a tempo or but -

Natural Trumpet Music and the Modern Performer A

NATURAL TRUMPET MUSIC AND THE MODERN PERFORMER A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Laura Bloss December, 2012 NATURAL TRUMPET MUSIC AND THE MODERN PERFORMER Laura Bloss Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________ _________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Chand Midha _________________________ _________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. Scott Johnston Dr. George R. Newkome _________________________ _________________________ School Director Date Dr. Ann Usher ii ABSTRACT The Baroque Era can be considered the “golden age” of trumpet playing in Western Music. Recently, there has been a revival of interest in Baroque trumpet works, and while the research has grown accordingly, the implications of that research require further examination. Musicians need to be able to give this factual evidence a context, one that is both modern and historical. The treatises of Cesare Bendinelli, Girolamo Fantini, and J.E. Altenburg are valuable records that provide insight into the early development of the trumpet. There are also several important modern resources, most notably by Don Smithers and Edward Tarr, which discuss the historical development of the trumpet. One obstacle for modern players is that the works of the Baroque Era were originally played on natural trumpet, an instrument that is now considered a specialty rather than the standard. Trumpet players must thus find ways to reconcile the inherent differences between Baroque and current approaches to playing by combining research from early treatises, important trumpet publications, and technical and philosophical input from performance practice essays. -

A Handbook of Cello Technique for Performers

CELLO MAP: A HANDBOOK OF CELLO TECHNIQUE FOR PERFORMERS AND COMPOSERS By Ellen Fallowfield A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham October 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Many new sounds and new instrumental techniques have been introduced into music literature since 1950. The popular approach to support developments in modern instrumental technique is the catalogue or notation guide, which has led to isolated special effects. Several authors of handbooks of technique have pointed to an alternative, strategic, scientific approach to technique as an ideological ideal. I have adopted this approach more fully than before and applied it to the cello for the first time. This handbook provides a structure for further research. In this handbook, new techniques are presented alongside traditional methods and a ‘global technique’ is defined, within which every possible sound-modifying action is considered as a continuous scale, upon which as yet undiscovered techniques can also be slotted. -

Multiphonics of the Grand Piano – Timbral Composition and Performance with Flageolets

Multiphonics of the Grand Piano – Timbral Composition and Performance with Flageolets Juhani VESIKKALA Written work, Composition MA Department of Classical Music Sibelius Academy / University of the Arts, Helsinki 2016 SIBELIUS-ACADEMY Abstract Kirjallinen työ Title Number of pages Multiphonics of the Grand Piano - Timbral Composition and Performance with Flageolets 86 + appendices Author(s) Term Juhani Topias VESIKKALA Spring 2016 Degree programme Study Line Sävellys ja musiikinteoria Department Klassisen musiikin osasto Abstract The aim of my study is to enable a broader knowledge and compositional use of the piano multiphonics in current music. This corpus of text will benefit pianists and composers alike, and it provides the answers to the questions "what is a piano multiphonic", "what does a multiphonic sound like," and "how to notate a multiphonic sound". New terminology will be defined and inaccuracies in existing terminology will be dealt with. The multiphonic "mode of playing" will be separated from "playing technique" and from flageolets. Moreover, multiphonics in the repertoire are compared from the aspects of composition and notation, and the portability of multiphonics to the sounds of other instruments or to other mobile playing modes of the manipulated grand piano are examined. Composers tend to use multiphonics in a different manner, making for differing notational choices. This study examines notational choices and proposes a notation suitable for most situations, and notates the most commonly produceable multiphonic chords. The existence of piano multiphonics will be verified mathematically, supported by acoustic recordings and camera measurements. In my work, the correspondence of FFT analysis and hearing will be touched on, and by virtue of audio excerpts I offer ways to improve as a listener of multiphonics. -

Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder

Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2010 ABSTRACT Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder In this paper, I describe my recent work, which is primarily focused around a dynamic tuning system, and the construction of new electro-acoustic instruments using this system. I provide an overview of my aesthetic and theoretical influences, in order to give some idea of the path that led me to my current project. I then explain the tuning system itself, which is a type of dynamically tuned just intonation, realized through electronics. The third section of this paper gives details on the design and construction of the instruments I have invented for my own compositional purposes. The final section of this paper gives an analysis of the first large-scale piece to be written for my instruments using my tuning system, Concerning the Nature of Things. Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder I. Why Adaptable Just Intonation on Invented Instruments? 1.1 - Influences 1.1.1 - Inspiration from Medieval and Renaissance music 1.1.2 - Inspiration from Harry Partch 1.1.3 - Inspiration from American country music 1.2 - Tuning systems 1.2.1 - Why just? 1.2.1.1 – Non-prescriptive pitch systems 1.2.1.2 – Just pitch systems 1.2.1.3 – Tempered pitch systems 1.2.1.4 – Rationale for choice of Just tunings 1.2.1.4.1 – Consideration of non-prescriptive -

Shivers on Speed (((2013(20132013)))) for Bass Flute, Bass Clarinet, Violin, Violoncello and Piano

Brigitta Muntendorf shivers on speed (((2013(20132013)))) for bass flute, bass clarinet, violin, violoncello and piano score shivers on speed (((2013(20132013)))) for bass flute, bass clarinet, violin, violoncello and piano commissioned by musikFabrik Instruments bass flute Bassflöte bass clarinet in B b Bassklarinette in Bb violin Violine violoncello Violoncello piano (+ mini vibrator made of rubber) Piano (+ Minivibrator aus Gummi) The score is transposed. Flute: the voice is written as sounding. Explanation of symbols Legende General instructions Allgemeine Spielanweisungen trembling/shivering: think of trembling hands or a trembled zittern/beben: diese Abschnitte sollen im wahrsten Sinne des voice – these parts have to played with trembling hands, Wortes “zittern” – Assoziationen an zitternde Hände oder eine with a shivering air stream. The musical result is an zittrige Stimme sollen musikalisch umgesetzt werden. Hier bei irregular and erratic repetition which is not controlled. Find entsteht eine unregelmäßige und unkontrollierbare Repetition, your own method to realize shivering notes. für die jeder Spieler seine eigene Methode entwickeln soll. vl./vc.: for example a mix between trem., salt., cl., Vl./Vlc: z. B. durch eine Kombination von trem. / salt. / cl. fl./clar.: for example irregular double/triple tounge with a Fl./Klar.: z. B. durch unregelmäßgie Doppel-, Trippelzunge lot of air mit möglichst viel Luft pno.: for example irregular repetitions by pressure/tense of Pno.: z. B. durch Fixierung des Handgelenks bei the wrist/forearm gleichzeitigem Anspannen des Unterarms. Dynamikangaben in Anführungs-zeichen geben immer die " " Volume indications in quotation marks indicate the intensity Intensität der Aktion an, nicht die resultierende Lautstärke. f of the action and not the resulting absolute volume of the action. -

Expressive Techniques

Expressive Techniques Expressive Techniques refers to the way a performer uses effects and particular techniques to create an individual interpretation of a piece of music. Expressive techniques are dependant on the sound source, certain instruments favour specific ways of creating expression e.g. Fretless string players are able to slide between notes sounding all the incremental changes but cannot use the wind technique of breath vibrato. Conversely there are many expressive techniques that are used by the majority of instruments, producing a variety of effects. For the purposes of the Music 1 course it is beneficial to know the most common techniques used. • Accent is a dynamic emphasis on a note to make it stronger thereby stressing its importance. • Glissando is the technique of rapidly sliding through a scale pattern. The effect varies markedly between different instruments due to the restraints of exact pitch divisions and the variety of production methods. • Legato is the method of playing smoothly, in a well connected graceful style. It produces a feeling of fluidity in the music and incorporates the use of slurs, where notes are merged together relying on the first note’s punctuation. • Staccato is the universal technique of playing the notes shorter than their written value, with the effect that they are detached from each other. • Tremolo is a technique of rapid amplitude variation. The same note is repetitively sounded over and over thereby increasing and decreasing the volume. • Vibrato is the technique of repetitively altering the pitch with small vibrational shifts up and down around a note. This is achieved by string bending or altering the flow of breath. -

Didgeridoo Notation

DIDGERIDOO NOTATION MARKOS KOUMOULAS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO DECEMBER 2018 © MARKOS KOUMOULAS, 2018 Abstract The didgeridoo is a unique musical instrument considered to be one of the world’s oldest instruments. It plays an integral part in Australian Aboriginal history, spirituality, rituals and ceremonies. Didgeridoo playing is solely based on oral tradition with varying techniques and interpretations among Aboriginal communities. For non-Aboriginal musicians and composers, the didgeridoo lacks the status of a “serious” instrument and is often viewed as a novelty instrument. This may be why there is a lack of didgeridoo notation and its misrepresentation in the western notation world. This paper presents a “Didgeridoo Notation Lexicon” which will allow non-didgeridoo composers to understand a readable legend and incorporate the didgeridoo into their compositions. The need for didgeridoo notation will be discussed and analyzed in comparison to previous notation attempts of composers and musicologists such as Sean O’Boyle, Liza Lim, Harold Kacanek and Wulfin Lieske. In the past, the inclusion of the didgeridoo in orchestral contexts has predominately been focussed on its associated Aboriginal imagery regarding dreamtime and spirituality. Conversely, my original composition fully integrates the didgeridoo within the orchestra as an equal instrument, not a focal point to advance a particular theme. I travelled to Cairns, Australia to interview world-renowned didgeridoo player, David Hudson. Hudson’s insight, experience and knowledge of the Aboriginal community supported the creation of a Didgeridoo Notation Lexicon. -

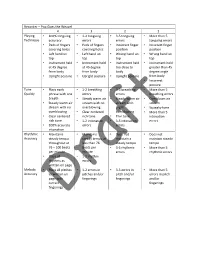

Recorder – Pop Goes the Weasel 4 3 2 1 Playing Technique • 100%

Recorder – Pop Goes the Weasel 4 3 2 1 Playing • 100% tonguing • 1-2 tonguing • 3-5 tonguing • More than 5 Technique accuracy errors errors tonguing errors • Pads of fingers • Pads of fingers • Incorrect finger • Incorrect finger covering holes covering holes position position • Left hand on • Left hand on • Wrong hand on • Wrong hand on top top top top • Instrument held • Instrument held • Instrument held • Instrument held at 45 degree at 45 degree too close to greater than 45 from body from body body degree angle • Upright posture • Upright posture • Upright posture from body • Incorrect posture Tone • Plays each • 1-2 breathing • 3-5 breathing • More than 5 Quality phrase with one errors errors breathing errors breath • Steady warm air • Steady warm air • Overblown air • Steady warm air stream with no stream with stream stream with no overblowing slight • Squeaky tone overblowing • Clear centered overblowing • More than 5 • Clear centered rich tone • Thin tone intonation rich tone • 1-2 intonation • 3-5 intonation errors • 100% accurate errors errors intonation Rhythmic • Maintains • Maintains • Does not • Does not Accuracy steady tempo steady tempo at maintain a maintain steady throughout at less than 76 steady tempo tempo 76 – 100 beats beats per • 3-5 rhythmic • More than 5 per minute minute errors rhythmic errors • Plays all • 1-2 rhythm rhythms as errors written on page Melodic • Plays all pitches • 1-2 errors in • 3-5 errors in • More than 5 Accuracy as written on pitches and/or pitch and/or errors in pitch page with fingerings -

Exploring Salvatore Sciarrino's Style Through L'opera Per Flauto

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 12-2010 Silence: Exploring Salvatore Sciarrino’s style through L’opera per flauto Megan R. Lanz University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Music Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Repository Citation Lanz, Megan R., "Silence: Exploring Salvatore Sciarrino’s style through L’opera per flauto" (2010). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 730. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/2002067 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SILENCE: AN EXPLORATION OF SALVATORE SCIARRINO’S STYLE THROUGH L’OPERA PER FLAUTO by Megan Re Lanz Bachelor of Music University of North Texas 2004 Master of Music University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2006 A doctoral document submitted in partial fulfillment