From Tape to Typedef: Compositional Methods in Electroacoustic Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Investigation of Nine Acousmatic Compositions

A PORTFOLIO OF ACOUSMATIC COMPOSITIONS BY DAVID HINDMARCH A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music School of Languages, Cultures, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham December 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This portfolio charts my development as a composer during a period of three years. The works it contains are all acousmatic; they investigate sonic material through articulation and gesture, and place emphasis on spatial movement through both stereophony and multi-channel environments. The portfolio is written as a personal journey, with minimal reference to academic thinking, exploring the development of my techniques when composing acousmatic music. At the root of my compositional work is the examination and analysis of recorded sounds; these are extrapolated from musical phrases and gestural movement, which form the basis of my musical language. The nine pieces of the portfolio thus explore, emphasise and develop the distinct properties of the recorded source sounds, deriving from them articulated phrasing and gesture which are developed to give sound objects the ability to move in a stereo or multi-channel space with expressive force and sonic clarity. -

Issue 189.Pmd

email: [email protected] NIGHTSHIFTwebsite: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every Oxford’s Music Magazine month. Issue 189 April 2011 YYYYYYoungoungoungoung KnivesKnivesKnivesKnives Go Pop! Out on their own and back with a brilliant new album photo: Cat Stevens NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net WILCO JOHNSON AND listings for the weekend, plus ticket DEACON BLUE are the latest details, are online at names added to this year’s www.oxfordjazzfestival.co.uk Cornbury Festival bill. The pair join already-announced headliners WITNEY MUSIC FESTIVAL returns James Blunt, The Faces and for its fifth annual run this month. Status Quo on a big-name bill that The festival runs from 24th April also includes Ray Davies, Cyndi through to 2nd May, featuring a Lauper, Bellowhead, Olly Murs, selection of mostly local acts across a GRUFF RHYS AND BELLOWHEAD have been announced as headliners The Like and Sophie Ellis-Bextor. dozen venues in the town. Amongst a at this year’s TRUCK FESTIVAL. Other new names on the bill are host of acts confirmed are Johnson For the first time Truck will run over three full days, over the weekend of prog-folksters Stackridge, Ben Smith and the Cadillac Blues Jam, 22nd-24th July at Hill Farm in Steventon. The festival will also enjoy an Montague & Pete Lawrie, Toy Phousa, Alice Messenger, Black Hats, increased capacity and the entire site has been redesigned to accommodate Hearts, Saint Jude and Jack Deer Chicago, Prohibition Smokers new stages. -

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano by Maria Payan, M.M., B.M. A Thesis In Music Performance Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved Dr. Lisa Garner Santa Chair of Committee Dr. Keith Dye Dr. David Shea Dominick Casadonte Interim Dean of the Graduate School May 2013 Copyright 2013, Maria Payan Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have started without the extraordinary help and encouragement of Dr. Lisa Garner Santa. The education, time, and support she gave me during my studies at Texas Tech University convey her devotion to her job. I have no words to express my gratitude towards her. In addition, this project could not have been finished without the immense help and patience of Dr. Keith Dye. For his generosity in helping me organize and edit this project, I thank him greatly. Finally, I would like to give my dearest gratitude to Donna Hogan. Without her endless advice and editing, this project would not have been at the level it is today. ii Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................. ii LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................. v 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ -

Unit 10.2 the Physics of Music Objectives Notes on a Piano

Unit 10.2 The Physics of Music Teacher: Dr. Van Der Sluys Objectives • The Physics of Music – Strings – Brass and Woodwinds • Tuning - Beats Notes on a Piano Key Note Frquency (Hz) Wavelength (m) 52 C 524 0.637 51 B 494 0.676 50 A# or Bb 466 0.717 49 A 440 0.759 48 G# or Ab 415 0.805 47 G 392 0.852 46 F# or Gb 370 0.903 45 F 349 0.957 44 E 330 1.01 43 D# or Eb 311 1.07 42 D 294 1.14 41 C# or Db 277 1.21 40 C (middle) 262 1.27 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piano_key_frequencies 1 Vibrating Strings - Fundamental and Overtones A vibration in a string can L = 1/2 λ1 produce a standing wave. L = λ Usually a vibrating string 2 produces a sound whose L = 3/2 λ3 frequency in most cases is constant. Therefore, since L = 2 λ4 frequency characterizes the pitch, the sound produced L = 5/2 λ5 is a constant note. Vibrating L = 3 λ strings are the basis of any 6 string instrument like guitar, L = 7/2 λ7 cello, or piano. For the fundamental, λ = 2 L where Vibration, standing waves in a string, L is the length of the string. The fundamental and the first 6 overtones which form a harmonic series http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vibrating_string Length of Piano Strings The highest key on a piano corresponds to a frequency about 150 times that of the lowest key. If the string for the highest note is 5.0 cm long, how long would the string for the lowest note have to be if it had the same mass per unit length and the same tension? If v = fλ, how are the frequencies and length of strings related? Other String Instruments • All string instruments produce sound from one or more vibrating strings, transferred to the air by the body of the instrument (or by a pickup in the case of electronically- amplified instruments). -

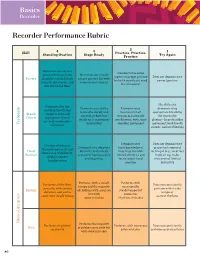

Recorder Performance Rubric

Basics Recorder Recorder Performance Rubric 2 Skill 4 3 Practice, Practice, 1 Standing Ovation Stage Ready Practice Try Again Demonstrates correct Demonstrates some posture with neck and Demonstrates mostly aspects of proper posture Does not demonstrate Posture shoulders relaxed, back proper posture but with but with significant need correct posture straight, chest open, and some inconsistencies for refinement feet flat on the floor Has difficulty Demonstrates low Demonstrates ability Demonstrates demonstrating and deep breath that to breathe deeply and inconsistent air appropriate breathing Breath supports even and control air flow, but stream, occasionally for successful Control appropriate flow of steady air is sometimes overblowing, with some playing—large shoulder air, with no shoulder Technique inconsistent shoulder movement movement, loud breath movement sounds, and overblowing Demonstrates Does not demonstrate Consistently fingers Demonstrates adequate basic knowledge of proper instrumental the notes correctly and Hand dexterity with mostly fingerings but with technique (e.g., incorrect shows ease of dexterity; Position consistent hand position limited dexterity and hand on top, holes displays correct and fingerings inconsistent hand not covered, limited hand position position dexterity) Performs with a steady Performs with Performs all rhythms Does not consistently tempo and the majority occasionally correctly, with correct perform with steady Rhythm of rhythms with accuracy steady tempo but duration, and with a tempo or but -

A Monthly Music, Arts and Literature Publication of the Carrboro Citizen Vol

MILLA MONTHLY MUSIC, ARTS AND LITERATURE PUBLICATION OF THE CARRBORO CITIZEN VOL. 4 + NO. 8 + MAY 2011 INSIDE: t FOUR-TOED SALAMANDERS t POETRY CONTEST WINNERS t KEVIN CALLAGHAN’S SQUASH CASSEROLE t HAW FESTIVAL casual dining & shopping in the heart of carrboro Carr Mill Mall gifts for mom ~ gifts for the graduate see individual merchants for gift certificates ali cat cvs miel bon bon anna’s tailor dsi comedy theater mulberry silks & alterations elmo’s diner the painted bird the bead store fedora panzanella carolina core pilates fleet feet rita’s italian ices carrboro yoga co. harris teeter sofia’s chicle language institute head over heels townsend, bertram & co. & café creativity matters jewelworks weaver st market 200 north greensboro street in carrboro ~ at the corner of weaver street ~ carrmillmall.com 2 carrborocitizen.com/mill + MAY 2011 MILL CELEBRATIONS ART NOTES pring is fully upon us, and area know that come June, things get all throughout this little town mighty slow around here. Some might and its environs are images recall more than one summer evening In the galleries once evoked by Thomas when the town appeared deserted and Burgeoning downtown Saxapahaw will see the opening of the town’s Wolfe. The green canopy has it seemed all there was to do was sit first artist co-op with the Sreturned, the moonlight is sifting and the quietly and relish. Friday, May 6 celebration nip in the night air is all but gone. It’s that So put on those heels, straighten that of the Saxapahaw Artists magical time of year here in the South, tie, pop a bottle of champagne and tell Gallery. -

Natural Trumpet Music and the Modern Performer A

NATURAL TRUMPET MUSIC AND THE MODERN PERFORMER A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Laura Bloss December, 2012 NATURAL TRUMPET MUSIC AND THE MODERN PERFORMER Laura Bloss Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________ _________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Chand Midha _________________________ _________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. Scott Johnston Dr. George R. Newkome _________________________ _________________________ School Director Date Dr. Ann Usher ii ABSTRACT The Baroque Era can be considered the “golden age” of trumpet playing in Western Music. Recently, there has been a revival of interest in Baroque trumpet works, and while the research has grown accordingly, the implications of that research require further examination. Musicians need to be able to give this factual evidence a context, one that is both modern and historical. The treatises of Cesare Bendinelli, Girolamo Fantini, and J.E. Altenburg are valuable records that provide insight into the early development of the trumpet. There are also several important modern resources, most notably by Don Smithers and Edward Tarr, which discuss the historical development of the trumpet. One obstacle for modern players is that the works of the Baroque Era were originally played on natural trumpet, an instrument that is now considered a specialty rather than the standard. Trumpet players must thus find ways to reconcile the inherent differences between Baroque and current approaches to playing by combining research from early treatises, important trumpet publications, and technical and philosophical input from performance practice essays. -

Connecting Time and Timbre Computational Methods for Generative Rhythmic Loops Insymbolic and Signal Domainspdfauthor

Connecting Time and Timbre: Computational Methods for Generative Rhythmic Loops in Symbolic and Signal Domains Cárthach Ó Nuanáin TESI DOCTORAL UPF / 2017 Thesis Director: Dr. Sergi Jordà Music Technology Group Dept. of Information and Communication Technologies Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain Dissertation submitted to the Department of Information and Communication Tech- nologies of Universitat Pompeu Fabra in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR PER LA UNIVERSITAT POMPEU FABRA Copyright c 2017 by Cárthach Ó Nuanáin Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 Music Technology Group (http://mtg.upf.edu), Department of Information and Communication Tech- nologies (http://www.upf.edu/dtic), Universitat Pompeu Fabra (http://www.upf.edu), Barcelona, Spain. III Do mo mháthair, Marian. V This thesis was conducted carried out at the Music Technology Group (MTG) of Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, Spain, from Oct. 2013 to Nov. 2017. It was supervised by Dr. Sergi Jordà and Mr. Perfecto Herrera. Work in several parts of this thesis was carried out in collaboration with the GiantSteps team at the Music Technology Group in UPF as well as other members of the project consortium. Our work has been gratefully supported by the Department of Information and Com- munication Technologies (DTIC) PhD fellowship (2013-17), Universitat Pompeu Fabra, and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program, as part of the GiantSteps project ((FP7-ICT-2013-10 Grant agreement no. 610591). Acknowledgments First and foremost I wish to thank my advisors and mentors Sergi Jordà and Perfecto Herrera. Thanks to Sergi for meeting me in Belfast many moons ago and bringing me to Barcelona. -

A Handbook of Cello Technique for Performers

CELLO MAP: A HANDBOOK OF CELLO TECHNIQUE FOR PERFORMERS AND COMPOSERS By Ellen Fallowfield A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham October 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Many new sounds and new instrumental techniques have been introduced into music literature since 1950. The popular approach to support developments in modern instrumental technique is the catalogue or notation guide, which has led to isolated special effects. Several authors of handbooks of technique have pointed to an alternative, strategic, scientific approach to technique as an ideological ideal. I have adopted this approach more fully than before and applied it to the cello for the first time. This handbook provides a structure for further research. In this handbook, new techniques are presented alongside traditional methods and a ‘global technique’ is defined, within which every possible sound-modifying action is considered as a continuous scale, upon which as yet undiscovered techniques can also be slotted. -

AN ANALYTICAL METHODOLOGY for ACOUSMATIC MUSIC David Hirst Teaching, Learning and Research Support Dept, University of Melbourne Email: [email protected]

AN ANALYTICAL METHODOLOGY FOR ACOUSMATIC MUSIC David Hirst Teaching, Learning and Research Support Dept, University of Melbourne email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper presents a procedure for the analysis of acousmatic music which was derived from the synthesis 2. DEFINING THE ANALYTICAL of top-down (knowledge driven) and bottom-up (data- METHODOLOGY driven) cognitive psychological views. The procedure is also a synthesis of research on primitive auditory scene The following procedure for the analysis of acousmatic analysis, combined with the research on acoustic, music was derived from the synthesis of top-down semantic, and syntactic factors in the perception of (knowledge driven) and bottom-up (data-driven) views everyday environmental sounds. The procedure can be since it has been found impossible to divorce one summarized as consisting of a number of steps: approach from the other. Segregation of sonic objects; Horizontal integration The procedure can be summarized as consisting of a and/or segregation; Vertical integration and/or number of steps: segregation; Assimilation and meaning. Segregation of sonic objects 1. Identify the sonic objects (or events). 1. INTRODUCTION 2. Establish the factors responsible for identification (acoustic, semantic, syntactic, Not only do we recognize sounds, but we ascribe and ecological) and their relative weightings (if meanings to sounds and meanings to the relationships possible). between sounds and other cognate phenomena. Music is Horizontal integration and/or segregation a meaningful and an emotional experience. Acousmatic 3. Identify streams (sequences or chains) which music uses recordings of everyday sounds, recordings of consist of sonic objects linked together and instruments and synthesized sounds. -

SUBJECTIVE EXPERIENCE Henry Hardy

SUBJECTIVE EXPERIENCE Henry Hardy This is the text of the thesis submitted by the author for the degree of DPhil to the Faculty of Literae Humaniores in the University of Oxford in Hilary Term 1976. No changes of substance have been made, but some subeditorial tidying has been done. Footnotes in square brackets are comments made by the author after the award of the degree. In the case of the first chapter, some of these are or derive from notes made as part of an attempt to prepare the chapter for publication, a project that was abandoned. Bold red arabic numbers in square brackets mark the beginning of the relevant page in the original type- script. Cross-references are linked to the pages of the present text. The thesis is in effect a second edition of the author’s BPhil thesis, ‘Subjective Experiences’. A searchable scan of the DPhil thesis as submitted is here. i Preface I should like to express my thanks to my supervisors, Anthony Kenny and David Pears, for their indispensable help and advice; and also to Samuel Guttenplan for useful discussion, and for much help with the practical side of preparing a thesis. HRDH Wolfson College April 1976 Note: This thesis is submitted under the new regulation of the Lit. Hum. board, whereby holders of the BPhil are permitted to submit a shorter thesis (of not less than 45,000 words) for the degree of DPhil. This thesis, while on the same subject as my BPhil thesis, is with the exception of a few short passages entirely new. -

SUNDAY 28Th Euros Childs @National Elf

SUNDAY 28th Euros Childs @National_Elf Euros Childs is a solo artist hailing from Pembrokeshire. Having fronted the band Gorky's Zygotic Mynci from 1991 until their demise in 2004, Euros went solo and released his debut album ‘Chops’ on the Wichita label in 2006, followed by a further 3 albums for the label: ‘Bore Da’, ‘The Miracle Inn’ (both 2007) and ‘Cheer Gone’ (2008). Euros set up his own record label National Elf in 2009 and to date has released 10 solo albums – including last year’s ‘Olion’, ‘Sweetheart’ (2015) ‘Refresh!’ (2016) ‘House Arrest’ (2017). He has toured extensively around the UK in the past 13 years. Sometimes with a band and occasionally alone with a piano. When asked by taxi drivers, hairdressers or distant relatives what kind of music he plays, Euros replies, 'It's pop music with a bit of folk music and thrown in. Sometimes synthesizers are used, sometimes pianos or guitars. But it's always rock n roll.” Wigwam @wigwamband Mae Wigwam yn fand roc a rol ifanc o Gaerdydd. Ffurfiwyd y grwp yn 2017 gan Gareth Scourfield, Elis Penri, Rhys Morris, Griff Daniels a Dan Jones. Gosododd Wigwam eu marc ar gystadleuaeth ‘Brwydr y Bandiau’ Yr Eisteddfod Genedlaethol yn 2018 ar ôl flwyddyn o chwarae gigs yn gyson dros Dde Cymru. Treuliodd y band hanner cyntaf 2018 yn gweithio yn galed ar eu halbwm cyntaf, Coelcerth, o dan arweiniad y cynhyrchwr chwedlonol Mei Gwynedd. Daeth y sengl, Mynd a Dod, cyn rhyddhau’r albwm, a chafodd ymateb gwych gan gynulleidfaoedd a DJs radio. Dilynodd yr albwm mis yn ddiweddarach, a chafodd ei henwi ar restr 10 albwm gorau 2019 Y Selar.