Actions and Sounds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Application of the Kinesthetic Sense: an Introduction of Body Awareness in Cello Pedagogy and Performance

The Application of the Kinesthetic Sense: An Introduction of Body Awareness in Cello Pedagogy and Performance A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music March 2014 by Gustavo Carpinteyro-Lara BM, University of Southern Mississippi, 2001 MM, Bowling Green State University, 2003 Committee Chair: Lee Fiser, BM Abstract This document on cello pedagogy and playing focuses on the importance of the kinesthetic sense as it relates to teaching and performance quality. William Conable, creator of body mapping, has described how the kinesthetic sense or movement sense provides information about the body’s position and size, and whether the body is moving and, if so, where and how. In addition Craig Williamson, pioneer of Somatic Integration, claims that the kinesthetic sense enables one to sense what the body is doing at any time, including muscular effort, tension, relaxation, balance, spatial orientation, distance, and proportion. Cellists can develop and awaken the kinesthetic sense in order to have conscious body awareness, and to understand that cello playing is a physical, aerobic, intellectual, and musical activity. This document describes the physical, motion, aerobic, anatomic, and kinesthetic approach to cello playing and is supported by somatic education methods, such as the Alexander Technique, Feldenkrais Method, and Yoga. By applying body awareness and kinesthesia in cello playing, cellists can have freedom, balance, ease in their movements, and an intelligent way of playing and performing. ii Copyright © 2014 by Gustavo Carpinteyro-Lara. -

The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck

Performance Practice Review Volume 9 Article 7 Number 1 Spring The aB roque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Vanscheeuwijck, Marc (1996) "The aB roque Cello and Its Performance," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 9: No. 1, Article 7. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199609.01.07 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Baroque Instruments The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck The instrument we now call a cello (or violoncello) apparently deve- loped during the first decades of the 16th century from a combina- tion of various string instruments of popular European origin (espe- cially the rebecs) and the vielle. Although nothing precludes our hypothesizing that the bass of the violins appeared at the same time as the other members of that family, the earliest evidence of its existence is to be found in the treatises of Agricola,1 Gerle,2 Lanfranco,3 and Jambe de Fer.4 Also significant is a fresco (1540- 42) attributed to Giulio Cesare Luini in Varallo Sesia in northern Italy, in which an early cello is represented (see Fig. 1). 1 Martin Agricola, Musica instrumentalis deudsch (Wittenberg, 1529; enlarged 5th ed., 1545), f. XLVIr., f. XLVIIIr., and f. -

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano by Maria Payan, M.M., B.M. A Thesis In Music Performance Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved Dr. Lisa Garner Santa Chair of Committee Dr. Keith Dye Dr. David Shea Dominick Casadonte Interim Dean of the Graduate School May 2013 Copyright 2013, Maria Payan Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have started without the extraordinary help and encouragement of Dr. Lisa Garner Santa. The education, time, and support she gave me during my studies at Texas Tech University convey her devotion to her job. I have no words to express my gratitude towards her. In addition, this project could not have been finished without the immense help and patience of Dr. Keith Dye. For his generosity in helping me organize and edit this project, I thank him greatly. Finally, I would like to give my dearest gratitude to Donna Hogan. Without her endless advice and editing, this project would not have been at the level it is today. ii Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................. ii LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................. v 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ -

Unit 10.2 the Physics of Music Objectives Notes on a Piano

Unit 10.2 The Physics of Music Teacher: Dr. Van Der Sluys Objectives • The Physics of Music – Strings – Brass and Woodwinds • Tuning - Beats Notes on a Piano Key Note Frquency (Hz) Wavelength (m) 52 C 524 0.637 51 B 494 0.676 50 A# or Bb 466 0.717 49 A 440 0.759 48 G# or Ab 415 0.805 47 G 392 0.852 46 F# or Gb 370 0.903 45 F 349 0.957 44 E 330 1.01 43 D# or Eb 311 1.07 42 D 294 1.14 41 C# or Db 277 1.21 40 C (middle) 262 1.27 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piano_key_frequencies 1 Vibrating Strings - Fundamental and Overtones A vibration in a string can L = 1/2 λ1 produce a standing wave. L = λ Usually a vibrating string 2 produces a sound whose L = 3/2 λ3 frequency in most cases is constant. Therefore, since L = 2 λ4 frequency characterizes the pitch, the sound produced L = 5/2 λ5 is a constant note. Vibrating L = 3 λ strings are the basis of any 6 string instrument like guitar, L = 7/2 λ7 cello, or piano. For the fundamental, λ = 2 L where Vibration, standing waves in a string, L is the length of the string. The fundamental and the first 6 overtones which form a harmonic series http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vibrating_string Length of Piano Strings The highest key on a piano corresponds to a frequency about 150 times that of the lowest key. If the string for the highest note is 5.0 cm long, how long would the string for the lowest note have to be if it had the same mass per unit length and the same tension? If v = fλ, how are the frequencies and length of strings related? Other String Instruments • All string instruments produce sound from one or more vibrating strings, transferred to the air by the body of the instrument (or by a pickup in the case of electronically- amplified instruments). -

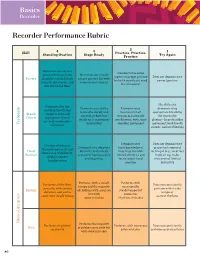

Recorder Performance Rubric

Basics Recorder Recorder Performance Rubric 2 Skill 4 3 Practice, Practice, 1 Standing Ovation Stage Ready Practice Try Again Demonstrates correct Demonstrates some posture with neck and Demonstrates mostly aspects of proper posture Does not demonstrate Posture shoulders relaxed, back proper posture but with but with significant need correct posture straight, chest open, and some inconsistencies for refinement feet flat on the floor Has difficulty Demonstrates low Demonstrates ability Demonstrates demonstrating and deep breath that to breathe deeply and inconsistent air appropriate breathing Breath supports even and control air flow, but stream, occasionally for successful Control appropriate flow of steady air is sometimes overblowing, with some playing—large shoulder air, with no shoulder Technique inconsistent shoulder movement movement, loud breath movement sounds, and overblowing Demonstrates Does not demonstrate Consistently fingers Demonstrates adequate basic knowledge of proper instrumental the notes correctly and Hand dexterity with mostly fingerings but with technique (e.g., incorrect shows ease of dexterity; Position consistent hand position limited dexterity and hand on top, holes displays correct and fingerings inconsistent hand not covered, limited hand position position dexterity) Performs with a steady Performs with Performs all rhythms Does not consistently tempo and the majority occasionally correctly, with correct perform with steady Rhythm of rhythms with accuracy steady tempo but duration, and with a tempo or but -

Basic Principles of the Alexander Technique Applied to Cello Pedagogy in Three Case Studies

Basic Principles of the Alexander Technique Applied to Cello Pedagogy in Three Case Studies A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music May, 2012 by Sae Rom Kwon BM, Eastman School of Music, 2003 MM, Eastman School of Music, 2005 Committee Chair: Yehuda Hanani Abstract The Alexander Technique helps its adherents improve posture and to use muscles and joints of the body efficiently. F. Mathias Alexander, an Australian actor, developed the technique in the 1890s to deal with difficulties he experienced on stage, such as chronic hoarseness. The technique attracted many followers in subsequent generations, including musicians, who are prone to physical problems due to long rehearsal hours. Elizabeth Valentine and others have sufficiently shown the effectiveness of the Alexander Technique for musicians through clinical studies. The focus of this document is more practical in nature. It consists of three case studies of individual cello students who struggle with specific problems to examine the results of practical solutions drawn from the principles of the Alexander Technique. Within five concurrent lessons, each student demonstrated consistent improvement in their problem areas. These case studies provide a basic introduction to this method and can help applied music teachers see the benefits of applying the Alexander Technique in the studio. ii Copyright © 2012 by Sae Rom Kwon. All rights reserved. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank all those in my life who contributed to this document. -

Natural Trumpet Music and the Modern Performer A

NATURAL TRUMPET MUSIC AND THE MODERN PERFORMER A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Laura Bloss December, 2012 NATURAL TRUMPET MUSIC AND THE MODERN PERFORMER Laura Bloss Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________ _________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Chand Midha _________________________ _________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. Scott Johnston Dr. George R. Newkome _________________________ _________________________ School Director Date Dr. Ann Usher ii ABSTRACT The Baroque Era can be considered the “golden age” of trumpet playing in Western Music. Recently, there has been a revival of interest in Baroque trumpet works, and while the research has grown accordingly, the implications of that research require further examination. Musicians need to be able to give this factual evidence a context, one that is both modern and historical. The treatises of Cesare Bendinelli, Girolamo Fantini, and J.E. Altenburg are valuable records that provide insight into the early development of the trumpet. There are also several important modern resources, most notably by Don Smithers and Edward Tarr, which discuss the historical development of the trumpet. One obstacle for modern players is that the works of the Baroque Era were originally played on natural trumpet, an instrument that is now considered a specialty rather than the standard. Trumpet players must thus find ways to reconcile the inherent differences between Baroque and current approaches to playing by combining research from early treatises, important trumpet publications, and technical and philosophical input from performance practice essays. -

The Search for Consistent Intonation: an Exploration and Guide for Violoncellists

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2017 THE SEARCH FOR CONSISTENT INTONATION: AN EXPLORATION AND GUIDE FOR VIOLONCELLISTS Daniel Hoppe University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.380 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hoppe, Daniel, "THE SEARCH FOR CONSISTENT INTONATION: AN EXPLORATION AND GUIDE FOR VIOLONCELLISTS" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 98. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/98 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

A Handbook of Cello Technique for Performers

CELLO MAP: A HANDBOOK OF CELLO TECHNIQUE FOR PERFORMERS AND COMPOSERS By Ellen Fallowfield A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham October 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Many new sounds and new instrumental techniques have been introduced into music literature since 1950. The popular approach to support developments in modern instrumental technique is the catalogue or notation guide, which has led to isolated special effects. Several authors of handbooks of technique have pointed to an alternative, strategic, scientific approach to technique as an ideological ideal. I have adopted this approach more fully than before and applied it to the cello for the first time. This handbook provides a structure for further research. In this handbook, new techniques are presented alongside traditional methods and a ‘global technique’ is defined, within which every possible sound-modifying action is considered as a continuous scale, upon which as yet undiscovered techniques can also be slotted. -

Multiphonics of the Grand Piano – Timbral Composition and Performance with Flageolets

Multiphonics of the Grand Piano – Timbral Composition and Performance with Flageolets Juhani VESIKKALA Written work, Composition MA Department of Classical Music Sibelius Academy / University of the Arts, Helsinki 2016 SIBELIUS-ACADEMY Abstract Kirjallinen työ Title Number of pages Multiphonics of the Grand Piano - Timbral Composition and Performance with Flageolets 86 + appendices Author(s) Term Juhani Topias VESIKKALA Spring 2016 Degree programme Study Line Sävellys ja musiikinteoria Department Klassisen musiikin osasto Abstract The aim of my study is to enable a broader knowledge and compositional use of the piano multiphonics in current music. This corpus of text will benefit pianists and composers alike, and it provides the answers to the questions "what is a piano multiphonic", "what does a multiphonic sound like," and "how to notate a multiphonic sound". New terminology will be defined and inaccuracies in existing terminology will be dealt with. The multiphonic "mode of playing" will be separated from "playing technique" and from flageolets. Moreover, multiphonics in the repertoire are compared from the aspects of composition and notation, and the portability of multiphonics to the sounds of other instruments or to other mobile playing modes of the manipulated grand piano are examined. Composers tend to use multiphonics in a different manner, making for differing notational choices. This study examines notational choices and proposes a notation suitable for most situations, and notates the most commonly produceable multiphonic chords. The existence of piano multiphonics will be verified mathematically, supported by acoustic recordings and camera measurements. In my work, the correspondence of FFT analysis and hearing will be touched on, and by virtue of audio excerpts I offer ways to improve as a listener of multiphonics. -

Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder

Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2010 ABSTRACT Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder In this paper, I describe my recent work, which is primarily focused around a dynamic tuning system, and the construction of new electro-acoustic instruments using this system. I provide an overview of my aesthetic and theoretical influences, in order to give some idea of the path that led me to my current project. I then explain the tuning system itself, which is a type of dynamically tuned just intonation, realized through electronics. The third section of this paper gives details on the design and construction of the instruments I have invented for my own compositional purposes. The final section of this paper gives an analysis of the first large-scale piece to be written for my instruments using my tuning system, Concerning the Nature of Things. Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder I. Why Adaptable Just Intonation on Invented Instruments? 1.1 - Influences 1.1.1 - Inspiration from Medieval and Renaissance music 1.1.2 - Inspiration from Harry Partch 1.1.3 - Inspiration from American country music 1.2 - Tuning systems 1.2.1 - Why just? 1.2.1.1 – Non-prescriptive pitch systems 1.2.1.2 – Just pitch systems 1.2.1.3 – Tempered pitch systems 1.2.1.4 – Rationale for choice of Just tunings 1.2.1.4.1 – Consideration of non-prescriptive -

The Cello Bow Held the Viol

Chelys 24, article 4 [47] THE CELLO BOW HELD THE VIOL- WAY; ONCE COMMON, BUT NOW ALMOST FORGOTTEN Mark Smith Ample evidence can be found tO show that many early cellists, including some of the most distinguished, held the bow with the hand under. It seems likely that hand-under bow-holds were more cOmmon than hand-over bow- holds for cellists (at least outside of France) until about 1730, and it is certain that some important solO cellists used a hand-under bow-hold not only until 1730, but well intO the second-half of the eighteenth century. TherefOre, a significant part of the early cellO repertory (perhaps some of it well-known today) must have been first played with the hand under the bow. Until now, hand-under bow-holds have been discussed only superficially by historians of the cello.1 With more information, I hope that some cellists may try such a bow-hold in the cOmpositions which were or may have been originally played that way. Iconographic evidence Little written information about any aspect of cellO technique is known earlier than the oldest dated cellO method, that of Corrette in 1741.2 However, there are hundreds of pictures Of cellists earlier than 1741, and these provide the bulk of information about bow-holds up tO that time (see Table 1). 1 have studied 259 paintings, drawings, engravings and other works of art depicting cellists, from the earliest-known example, dating from about 1535, up tO 1800.3 The number Of depictions is probably tOO small tO give an accurate estimation of the actual number and distributiOn of cellists using the twO bow-holds.