Didgeridoo Notation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Meaning of Yaroomba II

Revisiting the place name meaning of Yaroomba The Gaiarbau, ‘bunya country’ and ‘thick vine scrub’ connections (by Kerry Jones, Arnold Jones, Sean Fleischfresser, Rodney Jones, Lore?a Algar, Helen Jones & Genevieve Jones) The Sunshine Coast region, fiHy years ago, may have had the greatest use of place names within Queensland derived from Aboriginal language words, according to researcher, E.G. Heap’s 1966 local history arQcle, ‘In the Wake of the Rasmen’. In the early days of colonisaon, local waterways were used to transport logs and Qmber, with the use of Aboriginal labour, therefore the term ‘rasmen’. Windolf (1986, p.2) notes that historically, the term ‘Coolum District’ included all the areas of Coolum Beach, Point Arkwright, Yaroomba, Mount Coolum, Marcoola, Mudjimba, Pacific Paradise and Peregian. In the 1960’s it was near impossible to take transport to and access or communicate with these areas, and made that much more difficult by wet or extreme weather. Around this Qme the Sunshine Coast Airport site (formerly the Maroochy Airport) having Mount Coolum as its backdrop, was sQll a Naonal Park (QPWS 1999, p. 3). Figure 1 - 1925 view of coastline including Mount Coolum, Yaroomba & Mudjimba Island north of the Maroochy Estuary In October 2014 the inaugural Yaroomba Celebrates fesQval, overlooking Yaroomba Beach, saw local Gubbi Gubbi (Kabi Kabi) TradiQonal Owner, Lyndon Davis, performing with the yi’di’ki (didgeridoo), give a very warm welcome. While talking about Yaroomba, Lyndon stated this area too was and is ‘bunya country’. Windolf (1986, p.8) writes about the first Qmber-ge?ers who came to the ‘Coolum District’ in the 1860’s. -

Anastasia Bauer the Use of Signing Space in a Shared Signing Language of Australia Sign Language Typology 5

Anastasia Bauer The Use of Signing Space in a Shared Signing Language of Australia Sign Language Typology 5 Editors Marie Coppola Onno Crasborn Ulrike Zeshan Editorial board Sam Lutalo-Kiingi Irit Meir Ronice Müller de Quadros Roland Pfau Adam Schembri Gladys Tang Erin Wilkinson Jun Hui Yang De Gruyter Mouton · Ishara Press The Use of Signing Space in a Shared Sign Language of Australia by Anastasia Bauer De Gruyter Mouton · Ishara Press ISBN 978-1-61451-733-7 e-ISBN 978-1-61451-547-0 ISSN 2192-5186 e-ISSN 2192-5194 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. ” 2014 Walter de Gruyter, Inc., Boston/Berlin and Ishara Press, Lancaster, United Kingdom Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Țȍ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Acknowledgements This book is the revised and edited version of my doctoral dissertation that I defended at the Faculty of Arts and Humanities of the University of Cologne, Germany in January 2013. It is the result of many experiences I have encoun- tered from dozens of remarkable individuals who I wish to acknowledge. First of all, this study would have been simply impossible without its partici- pants. The data that form the basis of this book I owe entirely to my Yolngu family who taught me with patience and care about this wonderful Yolngu language. -

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano by Maria Payan, M.M., B.M. A Thesis In Music Performance Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved Dr. Lisa Garner Santa Chair of Committee Dr. Keith Dye Dr. David Shea Dominick Casadonte Interim Dean of the Graduate School May 2013 Copyright 2013, Maria Payan Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have started without the extraordinary help and encouragement of Dr. Lisa Garner Santa. The education, time, and support she gave me during my studies at Texas Tech University convey her devotion to her job. I have no words to express my gratitude towards her. In addition, this project could not have been finished without the immense help and patience of Dr. Keith Dye. For his generosity in helping me organize and edit this project, I thank him greatly. Finally, I would like to give my dearest gratitude to Donna Hogan. Without her endless advice and editing, this project would not have been at the level it is today. ii Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................. ii LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................. v 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ -

Download Fee Schedule

123 Engagement Opportunity Take up your invitation to connect your business with Your Benefits: Celebrity Bush Cook • Strategic alliance with RANGER NICK Australian identity. Who is Ranger Nick? Keeping heritage and cooking up a storm, he traditions alive, Ranger passes on his knowledge Often referred to as the Nick draws crowds at his to fellow adventurers, or • Effective "Guru" of camp oven performances, appealing mentoring groups of marketing tool. cooking, Ranger Nick is to young and old. youngsters, teaching them the master of keeping it • Professional the art of bush skills, simple and has been A previous environmental representation. cooking and outdoor demonstrating camp oven education support officer etiquette. • Brand and bush cooking skills and Ranger Guide from awareness. professionally since 2010, outback Queensland, A World Record travelling the country and Ranger Nick is putting his titleholder for the “Longest • Australia wide abroad. bush skills to use Damper”, Ranger Nick exposure wherever his travels take frequently appears on He has gained quite a through positive him, whipping up a radio, TV and podcasts, is reputation as the publicity. cracker of a meal with the author of three books, entertaining Aussie Bush whatever is in the the producer of Cook, who sings and has tuckerbox. educational products and plenty of yarns or poems has his own brand of to tell. When Ranger Nick is not merchandise. Performance & Availability Ranger Nick is available complexes, camping A true character, Ranger for camp oven cooking grounds, community Nick leaves a lasting demonstrations or events, fundraisers, impression wherever he promotional work product launches, goes and is a showcasing your promotional activities and conversational point long company’s products. -

Australian Curriculum: Science Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Australian Curriculum: Science Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures cross-curriculum priority Content elaborations and teacher background information for Years 7-10 JULY 2019 2 Content elaborations and teacher background information for Years 7-10 Australian Curriculum: Science Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures cross-curriculum priority Table of contents Introduction 4 Teacher background information 24 for Years 7 to 10 Background 5 Year 7 teacher background information 26 Process for developing the elaborations 6 Year 8 teacher background information 86 How the elaborations strengthen 7 the Australian Curriculum: Science Year 9 teacher background information 121 The Australian Curriculum: Science 9 Year 10 teacher background information 166 content elaborations linked to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures cross-curriculum priority Foundation 10 Year 1 11 Year 2 12 Year 3 13 Year 4 14 Year 5 15 Year 6 16 Year 7 17 Year 8 19 Year 9 20 Year 10 22 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures cross-curriculum priority 3 Introduction This document showcases the 95 new content elaborations for the Australian Curriculum: Science (Foundation to Year 10) that address the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures cross-curriculum priority. It also provides the accompanying teacher background information for each of the elaborations from Years 7 -10 to support secondary teachers in planning and teaching the science curriculum. The Australian Curriculum has a three-dimensional structure encompassing disciplinary knowledge, skills and understandings; general capabilities; and cross-curriculum priorities. It is designed to meet the needs of students by delivering a relevant, contemporary and engaging curriculum that builds on the educational goals of the Melbourne Declaration. -

John Gould and David Attenborough: Seeing the Natural World Through Birds and Aboriginal Bark Painting by Donna Leslie*

John Gould and David Attenborough: seeing the natural world through birds and Aboriginal bark painting by Donna Leslie* Abstract The English naturalist and ornithologist, John Gould, visited Australia in the late 1830s to work on a major project to record the birds of Australia. In the early 1960s, around 130 years later, the English naturalist, David Attenborough, visited Australia, too. Like his predecessor, Attenborough also brought with him a major project of his own. Attenborough’s objective was to investigate Aboriginal Australia and he wanted specifically to look for Aboriginal people still painting in the tradition of their ancestors. Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory was his destination. Gould and Attenborough were both energetic young men, and they each had a unique project to undertake. This essay explores aspects of what the two naturalists had to say about their respective projects, revealing through their own published accounts their particular ways of seeing and interpreting the natural world in Australia, and Australian Aboriginal people and their art, respectively. The essay is inspired by the author’s curated exhibition, Seeing the natural world: birds, animals and plants of Australia, held at the Ian Potter Museum of Art from 20 March to 2 June 2013. An exhibition at the Ian Potter Museum of Art, Seeing the natural world: birds, animals and plants of Australia currently showing from 20 March 2013 to 2 June 2013, explores, among other things, lithographs of Australian birds published by the English naturalist and ornithologist John Gould [1804-1881], alongside bark paintings by Mick Makani Wilingarr [c.1905-1985], an Aboriginal artist from Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory (Chisholm 1966; McCulloch 2006: 471; Morphy 2012). -

Unit 10.2 the Physics of Music Objectives Notes on a Piano

Unit 10.2 The Physics of Music Teacher: Dr. Van Der Sluys Objectives • The Physics of Music – Strings – Brass and Woodwinds • Tuning - Beats Notes on a Piano Key Note Frquency (Hz) Wavelength (m) 52 C 524 0.637 51 B 494 0.676 50 A# or Bb 466 0.717 49 A 440 0.759 48 G# or Ab 415 0.805 47 G 392 0.852 46 F# or Gb 370 0.903 45 F 349 0.957 44 E 330 1.01 43 D# or Eb 311 1.07 42 D 294 1.14 41 C# or Db 277 1.21 40 C (middle) 262 1.27 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piano_key_frequencies 1 Vibrating Strings - Fundamental and Overtones A vibration in a string can L = 1/2 λ1 produce a standing wave. L = λ Usually a vibrating string 2 produces a sound whose L = 3/2 λ3 frequency in most cases is constant. Therefore, since L = 2 λ4 frequency characterizes the pitch, the sound produced L = 5/2 λ5 is a constant note. Vibrating L = 3 λ strings are the basis of any 6 string instrument like guitar, L = 7/2 λ7 cello, or piano. For the fundamental, λ = 2 L where Vibration, standing waves in a string, L is the length of the string. The fundamental and the first 6 overtones which form a harmonic series http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vibrating_string Length of Piano Strings The highest key on a piano corresponds to a frequency about 150 times that of the lowest key. If the string for the highest note is 5.0 cm long, how long would the string for the lowest note have to be if it had the same mass per unit length and the same tension? If v = fλ, how are the frequencies and length of strings related? Other String Instruments • All string instruments produce sound from one or more vibrating strings, transferred to the air by the body of the instrument (or by a pickup in the case of electronically- amplified instruments). -

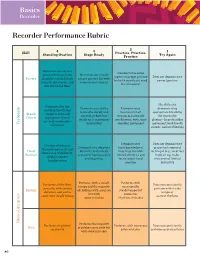

Recorder Performance Rubric

Basics Recorder Recorder Performance Rubric 2 Skill 4 3 Practice, Practice, 1 Standing Ovation Stage Ready Practice Try Again Demonstrates correct Demonstrates some posture with neck and Demonstrates mostly aspects of proper posture Does not demonstrate Posture shoulders relaxed, back proper posture but with but with significant need correct posture straight, chest open, and some inconsistencies for refinement feet flat on the floor Has difficulty Demonstrates low Demonstrates ability Demonstrates demonstrating and deep breath that to breathe deeply and inconsistent air appropriate breathing Breath supports even and control air flow, but stream, occasionally for successful Control appropriate flow of steady air is sometimes overblowing, with some playing—large shoulder air, with no shoulder Technique inconsistent shoulder movement movement, loud breath movement sounds, and overblowing Demonstrates Does not demonstrate Consistently fingers Demonstrates adequate basic knowledge of proper instrumental the notes correctly and Hand dexterity with mostly fingerings but with technique (e.g., incorrect shows ease of dexterity; Position consistent hand position limited dexterity and hand on top, holes displays correct and fingerings inconsistent hand not covered, limited hand position position dexterity) Performs with a steady Performs with Performs all rhythms Does not consistently tempo and the majority occasionally correctly, with correct perform with steady Rhythm of rhythms with accuracy steady tempo but duration, and with a tempo or but -

Music Braille Code, 2015

MUSIC BRAILLE CODE, 2015 Developed Under the Sponsorship of the BRAILLE AUTHORITY OF NORTH AMERICA Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2016 by the Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be duplicated but not altered or sold. ISBN: 978-0-9859473-6-1 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9859473-7-8 (Braille) Printed by the American Printing House for the Blind. Copies may be purchased from: American Printing House for the Blind 1839 Frankfort Avenue Louisville, Kentucky 40206-3148 502-895-2405 • 800-223-1839 www.aph.org [email protected] Catalog Number: 7-09651-01 The mission and purpose of The Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats, the ease of production by various methods, and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii BANA Music Technical Committee, 2015 Lawrence R. Smith, Chairman Karin Auckenthaler Gilbert Busch Karen Gearreald Dan Geminder Beverly McKenney Harvey Miller Tom Ridgeway Other Contributors Christina Davidson, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Richard Taesch, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Roger Firman, International Consultant Ruth Rozen, BANA Board Liaison iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................. -

Why Do Singers Sing in the Way They

Why do singers sing in the way they do? Why, for example, is western classical singing so different from pop singing? How is it that Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballe could sing together? These are the kinds of questions which John Potter, a singer of international repute and himself the master of many styles, poses in this fascinating book, which is effectively a history of singing style. He finds the reasons to be primarily ideological rather than specifically musical. His book identifies particular historical 'moments of change' in singing technique and style, and relates these to a three-stage theory of style based on the relationship of singing to text. There is a substantial section on meaning in singing, and a discussion of how the transmission of meaning is enabled or inhibited by different varieties of style or technique. VOCAL AUTHORITY VOCAL AUTHORITY Singing style and ideology JOHN POTTER CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 IRP, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, United Kingdom 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia © Cambridge University Press 1998 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1998 Typeset in Baskerville 11 /12^ pt [ c E] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library library of Congress cataloguing in publication data Potter, John, tenor. -

66Th Miff Announces Full Program

66TH MIFF ANNOUNCES FULL PROGRAM GURRUMUL WORLD PREMIERE AT CLOSING NIGHT JANE CAMPION, MELISSA GEORGE AND LUCA GUADAGNINO LEAD GUEST LINE-UP SALLY POTTER AND PIONEERING WOMEN RETROSPECTIVES UNVEILED MELBOURNE, 12 JULY 2017 – Celebrating its 66th year, the Melbourne International FIlm Festival (MIFF) unleashes its full program with a mammoth line-up of more than 358 films representing 68 countries, including 251 features, 88 shorts, 17 Virtual Reality experiences, 12 MIFF Talks events, 31 world premieres and 135 Australian premieres. It all happens over 18 days, spanning 13 venues across Melbourne, from 3 to 20 August 2017. “What a pleasure it is to launch this year’s Melbourne International Film Festival,” said Artistic Director Michelle Carey. “This year’s program offers audiences an amazing opportunity to explore new worlds through film – from our Pioneering Women and Sally Potter retrospectives to the return of our Virtual Reality program as well as a particularly strong line-up of special events, we can’t wait to open the doors to MIFF 2017.” After kicking-off the festival with the Opening Night Gala screening of Greg McLean’s MIFF Premiere Fund-supported JUNGLE, presented by Grey Goose Vodka, the festival will wind up with the world premiere CLOSING NIGHT screening of Paul Williams’ GURRUMUL. A profound exploration of the life and music of revered Australian artist Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu, the film uses the tools of the artist’s music – chord, melody, song – and the sounds of the land to craft an audio-first cinematic experience, offering a rare insight into a reclusive master. After the film, the audience will enjoy MIFF’s famous Closing Night party at the Festival Lounge. -

2017 Program PDF 1.12 MB

► JACQUES TOURNEUR Thursday 26 October at 6.00pm RE-DISCOVERED Friday 27 October at 6.00pm OPENING NIGHT CAT PEOPlE HOME BY CHRISTMAS Director: Jacques Tourneur | 1942 | 74 mins | USA | Classified M Director: Gaylene Preston | 2010 | 92 mins | New Zealand | Classified M Perhaps Tourneur’s best known film, CAT woman obsessed with ancient legends and Gaylene Preston’s poignant drama based on war, to find that his world has changed. Tony PEOPlE is a superb example of his art. Made panthers, the film was one of a series that her interviews with her father, gives Barry rises to the challenge superbly, giving for a tiny budget that would have crippled Tourneur made for producer Val Lewton. In Australian actor, Tony Barry , a rare a performance that reveals the depths of other directors, Tourneur delivered a all of them, but especially CAT PEOPlE , opportunity to move into a leading role Ed’s experiences that he cannot express in psychological thriller that created suspense Tourneur makes a virtue of his sparse worthy of his talents. He plays Ed, who enlists words. Criminally unknown in Australia, this through sound and shadow, through a resources to build work that critic James in the NZ Army in 1940 and heads overseas film is a seamless and innovative hybrid of brooding sense of paranoia, rather than Agee described as “consistently alive, leaving his pregnant wife behind, promising re-enactment and authentic dialogue. special effects: the art of showing less and limber, poetic, humane, (and) eager he’ll be home by Christmas. Four years later “A gentle, funny, utterly truthful film” suggesting more.