Re-Thinking Raj Patel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orientalisms in Bible Lands

eoujin ajiiiBOR Rice ^^ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES GIFT OF Carl ©ton Shay [GREEN FUND BOOK No. 16] Orientalisms IN Bible Lands GIVING LIGHT FROM CUSTOMS, HABITS, MANNERS, IMAGERY, THOUGHT AND LIFE IN THE EAST FOR BIBLE STUDENTS. BY EDWIN WILBUR RICE, D. D. AUTHOR OK " " Our Sixty-Six Sacred Commentaries on the Gospels and The Acts ; " " " " of the Bible ; Handy Books ; People's Dictionary Helps for Busy Workers," etc. PHILADELPHIA: The American Sunday-School Union, 1816 Chestnut Street. Copyright, 1910,) by The American Sunday-School Union —— <v CONTENTS. • • • • • I. The Oriental Family • • • " ine The Bible—Oriental Color.—Overturned Customs.— "Father."—No Courtship.—The Son.—The Father Rules.— Patriarchal Rule.—Semites and Hebrews. Betrothal i6 II. Forming the Oriental Family: Love-making Unknown. — Girl's Gifts. — Wife-seeking. Matchmaking.—The Contract.—The Dowry.—How Set- tied.—How Paid.—Second Marriage.—Exempt from Duties. III. Marriage Processions • • • • 24 Parades in Public—Bridal Costumes.—Bnde's Proces- sion (In Hauran,—In Egypt and India).—Bridegroom's Procession.—The Midnight Call.—The Shut Door. IV. Marriage Feasts • 3^ Great Feasts.—Its Magnificence.—Its Variety.—Congratula- tions.—Unveiling the Face.—Wedding Garment.—Display of Gifts.—Capturing the Bride.—In Old Babylonia. V. The Household ; • • • 39 Training a Wife. —Primitive Order.—The Social Unit. Childless. —Divorce. VI. Oriental Children 43 Joy Over Children.—The Son-heir.-Family Names.—Why Given?—The Babe.—How Carried.—Child Growth. Steps and Grades. VII. Oriental Child's Plays and Games 49 Shy and Actors.—Kinds of Plavs.—Toys in the East.— Ball Games.—Athletic Games.—Children Happy.—Japanese Children. -

Starters Mains Kemia Plates Desserts Nibbles Aperitifs Blue Man Wrap

Nibbles Aperitifs Mslalla zaytoun £3.5 Batata £4 Pomegranate prosecco Blue man marinated olives Handcut Rosemary fries or spicy wedges served Gin Martini Agroum zayton m’hams £5 with harissa mayo Aperol Spritz Bread served with homemade dips houmous and Berber toast £7 Kenyan Dawa olive tapenade Grilled goats cheese with honey and almonds Dark & Stormy Sferia £6 Choufleur makli £6 Old Fashioned Cheesy Algerian dumplings with harissa mayo Cauliflower koftas Espresso Martini Fatima’s toast £7 Sardina m’charmla £7 Algerian spiced mackerel rillets spread on flat bread Marinated anchovies served with salad £8 each or add a nibble for £12 Starters Halloumi Kaswila bel Romman £7 Crab Brik bel Toum £8 Grilled apple and halloumi topped with honey and pomegranate Crab meat in house spices wrapped in filo pastry on caramelised onion, served with carrot and rosewater served with cucumber relish and red pepper sauce Jej Charmoula bel Zaatar £8 Algerian Mixed Salad £6.50 Spicy grilled marinated chicken with speciality spices, yogurt & mint leben A raw salad with artichoke, courgettes and chickpeas sauce on naan Falafel karentita £7 Merguez A Dar bel Bisbas £8.50 Algerian falafel served with mint cucumber and tahini dressing House speciality spicy lamb sausages served with fennel, spinach and harissa Mains Khrouf bel Barkok wal Loz £14 Khodra £13 Lamb tagine served with homemade bread, couscous and harissa. Seasonal vegetable tagine served with homemade bread, couscous and harissa One of the most famous dishes across North Africa Zaalouk Adas Slata £11 Jej bel Mash Mash £14 Famous North African spiced tomato and grilled aubergine stew Chicken and apricot tagine served with homemade bread, couscous and harissa served with puy lentil and basil salad Algerian Bouillabaisse £14 Shakshuka £11 Famous Mediterranean dish with a North African twist, Mixed north African vegetables in a rich tomato sauce served with a cracked similar to a fish tagine with shellfish and whitefish of the day egg and baked. -

Copy of Chargrill

chargrill small plates / mezze ideal for sharing ZEYTIN Marinated mixed olives 3.00 V VG SHEPHERDS SALAD finely chopped tomatoes, cucumber, 4.95 V VG CACIK (tzatziki) yogurt with cucumber, garlic & mint 4.00 V green pepper, onion & flat leaf parsley in lemon dressing EZME SALSA Finely chopped tomatoes, 4.00 V VG GRILLED HALLOUMI served on rocket salad drizzled with 6.95 V onions, parsley & hot 'pul biber' chilli flakes pomegranate molasses TRUVA HUMMUS crushed chickpeas, tahini & garlic 4.00 V VG SIGARA BOREK deep fried filo pastry filled with feta 6.95 V BABA GHANOUSH chargrilled aubergine dip with chilli, 4.25 V VG cheese, spinach & herbs lemon & garlic KALAMARI herb marinated calamari deep fried, with 5.95 SARMA vine leaves stuffed with rice & herbs served on 4.00 V VG thousand island dressing & lemon bed of salad, drizzled with pomegranate molasses FRIED LAMB LIVER Peppered lambs liver fried together 5.95 RED PEPPER HUMMUS crushed chickpea with tahini, 4.00 V VG with red onion & flat bread pureed red pepper & mild chilli FALAFEL deep fried chickpea & fava bean balls drizzled 5.95 V VG GREEK FETA SALAD Mixed salad leaves, tomato, 5.95 V with a tahini dressing, served on bed of hummus cucumber onion, feta & olives SPICY POTATO (batata harra) cubes of golden fried 4.00 V VG COUS COUS SALAD cous cous with tomatoes, finely 4.95 V VG potato, seasoned with coriander, garlic and lemon chopped parsley, mint & onion WHITE BAIT Fried white bait served with lemon 5.95 GARLIC & CORIANDER FLATBREAD 2.50 VVG mayonnaise big plates MEAT BALLS lightly -

No Greens in the Forest?

No greens in the forest? Note on the limited consumption of greens in the Amazon Titulo Katz, Esther - Autor/a; López, Claudia Leonor - Autor/a; Fleury, Marie - Autor/a; Autor(es) Miller, Robert P. - Autor/a; Payê, Valeria - Autor/a; Dias, Terezhina - Autor/a; Silva, Franklin - Autor/a; Oliveira, Zelandes - Autor/a; Moreira, Elaine - Autor/a; En: Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae vol. 81 no. 4 (2012). Varsovia : Polish En: Botanical Society, 2012. Varsovia Lugar Polish Botanical Society Editorial/Editor 2012 Fecha Colección Alimentos; Alimentación; Pueblos indígenas; Etnobotánica; Plantas; Hierbas; Temas Colombia; Perú; Guayana Francesa; Brasil; Amazonia; Venezuela; Artículo Tipo de documento "http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/engov/20140508112743/katz_no_greens_in_the_forest.pdf" URL Reconocimiento CC BY Licencia http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/deed.es Segui buscando en la Red de Bibliotecas Virtuales de CLACSO http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales (CLACSO) Conselho Latino-americano de Ciências Sociais (CLACSO) Latin American Council of Social Sciences (CLACSO) www.clacso.edu.ar Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae Journal homepage: pbsociety.org.pl/journals/index.php/asbp INVITED REVIEW Received: 2012.10.15 Accepted: 2012.11.19 Published electronically: 2012.12.31 Acta Soc Bot Pol 81(4):283–293 DOI: 10.5586/asbp.2012.048 No greens in the forest? Note on the limited consumption of greens in the Amazon Esther Katz1*, Claudia Leonor López2, Marie Fleury3, Robert P. Miller4, -

Dutch Delicacies

Stroopwafel Drop Oliebol Kroket Dutch Delicacies Each country has its own specialties ERWTENSOEP (PEA SOUP) regarding food, as well as snacks, candy and Quite a few countries have some sort of soup made from anything you can eat or drink. Although peas, but not one of these variations is as dense and fill- ing as the Dutch variety. This pea soup, also called ‘snert’ the Dutch cuisine is not renowned for its in the Dutch vernacular, is made from celeriac, (split) fine foods and dishes, we do have some peas, and leek, often supplemented with ingredients like products and dishes that will certainly potatoes, carrots, unions, pork and smoked sausage. Traditionally, this winter soup is served with rye bread appeal to gourmets. When you pay the spread with smoked bacon, cheese or butter. Netherlands a visit, be sure to try – and no doubt, enjoy – the taste of one or more of KROKET (CROQUETTE) One of the most popular Dutch snacks is the ‘kroket’: the products mentioned below. this is a deep-fried ragout filled snack coated with bread- 36 MeetingInternational.org Culinary Meeting crumbs. These are consumed during lunchtime, but also accompany a portion of chips. A favorite Genuine regional products quicky snack is a ‘kroket’ from the ‘automatiek’, Of course this very succinct choice selection is not complete which is in fact a vending machine mounted in without mentioning the many hard cheeses and the raw mat- a side wall of the Dutch equivalent of a fish and ties herring. But the Netherlands also boast various regional chips shop. -

MENU Prix TTC En Euros

Cold Mezes Hot Mezes Hummus (vg) ............................... X Octopus on Fire ............................ X Lamb Shish Fistuk (h) .................. X Chickpeas, tahini, lemon, garlic, Smoked hazelnut, red pepper sauce Green pistachio, tomato, onion, green sumac, olive oil, pita bread chilli pepper, sumac salad Moroccan Rolls ............................. X Tzatziki (v) ................................... X Filo pastry, pastirma, red and yellow Garlic Tiger Prawns ...................... X Fresh yogurt, dill oil, pickled pepper bell, smoked cheese, harissa Garlic oil, shaved fennel salad, red cucumber, dill tops, pita bread yoghurt chilli pepper, zaatar Babaganoush (vg) ......................... X Pastirma Mushrooms .................... X Spinach Borek (v) ......................... X Smoked aubergine, pomegranate Cured beef, portobello and oysters Filo pastry, spinach, feta cheese, pine molasses, tahini, fresh mint, diced mushrooms, poached egg yolk, sumac nuts, fresh mint tomato, pita bread Roasted Cauliflower (v) ................ X Chicken Mashwyia ........................ X Taramosalata ................................ X Turmeric, mint, dill, fried capers, Wood fire chicken thighs, pickled Cod roe rock, samphire, bottarga, garlic yoghurt onion, mashwyia on a pita bread lemon zest, spring onion, pita bread Grilled Halloumi (v) ..................... X Meze Platter .................................. X Beetroot Borani (v) ...................... X Chargrilled courgette, kalamata Hummus, Tzatziki, Babaganoush, Walnuts, nigella seeds, -

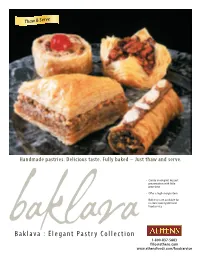

Athens Baklava Varieties Are Delicious on Their Own, but Try the Following Serving Suggestions to Create a Signature Item to Suit Your Menu

rve Se Thaw & Hurricane Shrimp Handmade pastries. Delicious taste. Fully baked – Just thaw and serve. • Create an elegant dessert presentation with little prep time • Offer a high-margin item • Bulk trays are available for in-store bakery/deli and foodservice Baklava : Elegant Pastry Collection 1-800-837-5683 [email protected] www.athensfoods.com/foodservice Classic Baklava Triangles (48 ct.) Pecan Blossoms (35 ct.) Chocolate Almond Rolls (45 ct.) Classic Baklava Rectangles (72 ct.) This classic treat contains a rich blend of spiced nuts Flaky fillo layers bursting with glazed natural pecans, Hand-rolled fillo tubes filled with a delicate blend Our delicious baklava is a sumptuous treat for any layered in sheets of crisp, flaky Athens Fillo® Dough, almonds and walnuts. Topped with honey syrup and of ground and chopped walnuts and sweet occasion. Rich blend of spiced nuts layered between finished with a sweet honey syrup. Scrumptious! whole pecans. Irresistible! chocolate. Baked crispy and then glazed. Finished crisp and flaky sheets of Athens Fillo® Dough, finished with hand-piped chocolate and natural sliced with a sweet honey syrup. Classic! almonds. As beautiful as they are delicious! elegant and Handmade delicious Appearance, Sensational Flavors, Excellentdessert Profitability. specialties Athens presents the finest collection of dessert specialties you’ll find anywhere - our collection has something for everyone. Beautiful presentation, delectable combinations, ready to serve, and with a high profit margin. You’ll love our sweet and -

Dessert Menu

MADO MENU DESSERTS From Karsambac to Mado Ice cream: Flavor’s Journey throughout the History From Karsambac to Mado Ice-cream: Flavors’ Journey throughout the History Mado Ice-cream, which has earned well-deserved fame all over the world with its unique flavor, has a long history of 300 years. This is the history of the “step by step” transformation of a savor tradition called Karsambac (snow mix) that entirely belongs to Anatolia. Karsambac is made by mixing layers of snow - preserved on hillsides and valleys via covering them with leaves and branches - with fruit extracts in hot summer days. In time, this mixture was enriched with other ingredients such as milk, honey, and salep, and turned into the well-known unique flavor of today. The secret of the savor of Mado Ice-cream lies, in addition to this 300 year-old tradition, in the climate and geography where it is produced. This unique flavor is obtained by mixing the milk of animals that are fed on thyme, milk vetch and orchid flowers on the high plateaus on the hillsides of Ahirdagi, with sahlep gathered from the same area. All fruit flavors of Maras Ice-cream are also made through completely natural methods, with pure cherries, lemons, strawberries, oranges and other fruits. Mado is the outcome of the transformation of our traditional family workshop that has been ice-cream makers for four generations, into modern production plants. Ice-cream and other products are prepared under cutting edge hygiene and quality standards in these world-class modern plants and are distributed under necessary conditions to our stores across Turkey and abroad; presented to the appreciation of your gusto, the esteemed gourmet. -

To-Go Menu SALADS with GARLIC SAUCE CHICKEN SHAWERMA STREET

SAMPLERS ATHENA’S WRAPS *ADD HUMMUS AND SALAD FOR $2* V DIP SAMPLER ......................................... 7 HUMMUS, GRECIAN DIP, BABA GHANOUSH & LABNEH CHICKEN SHAWERMA ............................... 7 8 ATHENA’S SAMPLER FOR ONE ................ 7 GRECIAN DIP, LETTUCE & TOMATOES FALAFEL, FRIED EGGPLANT, KIBBEH & MEAT GRAPE LEAF GYRO .............................................................. 7 8 GREEK MEZA V ......................................... 4 GRECIAN DIP, LETTUCE, TOMATOES & ONIONS TOMATOES, CUCUMBERS, ONIOINS, TURNIPS, PICKLES & OLIVES BEEF KOFTA ................................................ 7 MEAT FEAST ................................................. 25 GRECIAN DIP, LETTUCE, TOMATOES & ONIONS CHOOSE FIVE DIFFERENT SKEWER ITEMS BEEF SHAWERMA STREET ....................... 11 GRILLED 12-INCH BEEF WRAP, CUT INTO PIECES & SERVED To-Go Menu SALADS WITH GARLIC SAUCE CHICKEN SHAWERMA STREET .............. 10 GRILLED 12-INCH CHICKEN WRAP, CUT INTO PIECES & SERVED FETA SALAD .................................................. 6 WITH GARLIC SAUCE LETTUCE, FETA CHEESE & ATHENA’S SPECIAL SALAD DRESSING HALLOUMI CHEESE V ........................... 8 GREEK SALAD ............................................... 7 DRIED MINT, TOMATOES & BLACK OLIVES LETTUCE, FETA CHEESE, TOMATOES, CUCUMBERS, BLACK OLIVES & EGGPLANT V ............................................. 8 ATHENA’S SPECIAL SALAD DRESSING ARABIC SALAD .............................................. 7 FETA CHEESE, ONIONS & TOMATOES V HOURS FRESH-CUT TOATOES, CUCUMBERS, PARSLEY, -

Fresh Halal Authentic Mediterranean

ABOUT CAIRO KEBAB HOURS OF OPERATION Located in the heart of Lincoln Park, Cairo Kebab Sunday - Thursday: 11am - 10 pm offers an eclectic blend of cuisines from all around Friday - Saturday: 11am - 11pm the Mediterranean, with specialty traditional Egyptian dishes you won’t find at other Middle Eastern restaurants. CONTACT US Our food is freshly prepared, halal, and with a large Phone: 773-687-8413 selection of vegetarian and vegan options. At the Fax: 773-687-8437 heart of Cairo Kebab is the legacy of the legendary Email: [email protected] Saleh family chef Hussein “Baba” Saleh, who passed down his love for cooking to his brother Ahmed, our head chef. CATERING AVAILABLE Ahmed will delight you with his unique take on the Middle Eastern standards that you know and love, as well as his own authentic family recipes. We welcome you to enjoy our Middle Eastern hospitality here in the restaurant, or request pick- up or delivery. We also cater for all types of events, large or small. FRESH HALAL AUTHENTIC MEDITERRANEAN 1524 W Fullerton Ave, • Chicago, IL 60614 www.cairokebab.com STARTERS SANDWICHES SOUPS & SALADS Served with pita bread Served wrapped in pita bread with optional hot sauce Tabbouleh V Sm: $3.5 Lg: $5.5 Bulgur wheat, fresh mint, tomato, parsley, and onion, with Hummus V Sm: $4 Lg: $6 Falafel Sandwich V $5.99 an olive oil and lemon juice dressing Ground chickpeas blended with tahini (sesame) sauce and wrapped with jerusalem salad and pickles seasonings Egyptian Salad V Sm: $4.5 Lg: $6.5 Chicken Kebab Sandwich $6.99 Fresh vegetables -

Festiwal Chlebów Świata, 21-23. Marca 2014 Roku

FESTIWAL CHLEBÓW ŚWIATA, 21-23. MARCA 2014 ROKU Stowarzyszenie Polskich Mediów, Warszawska Izba Turystyki wraz z Zespołem Szkół nr 11 im. Władysława Grabskiego w Warszawie realizuje projekt FESTIWAL CHLEBÓW ŚWIATA 21 - 23 marca 2014 r. Celem tej inicjatywy jest promocja chleba, pokazania jego powszechności, ale i równocześnie różnorodności. Zaplanowaliśmy, że będzie się ona składała się z dwóch segmentów: pierwszy to prezentacja wypieków pieczywa według receptur kultywowanych w różnych częściach świata, drugi to ekspozycja producentów pieczywa oraz związanych z piekarnictwem produktów. Do udziału w żywej prezentacji chlebów świata zaprosiliśmy: Casa Artusi (Dom Ojca Kuchni Włoskiej) z prezentacją piady, producenci pity, macy oraz opłatka wigilijnego, Muzeum Żywego Piernika w Toruniu, Muzeum Rolnictwa w Ciechanowcu z wypiekiem chleba na zakwasie, przedstawiciele ambasad ze wszystkich kontynentów z pokazem własnej tradycji wypieku chleba. Dodatkowym atutem będzie prezentacja chleba astronautów wraz osobistym świadectwem Polskiego Kosmonauty Mirosława Hermaszewskiego. Nie zabraknie też pokazu rodzajów ziarna oraz mąki. Realizacją projektu będzie bezprecedensowa ekspozycja chlebów świata, pozwalająca poznać nie tylko dzieje chleba, ale też wszelkie jego odmiany występujące w różnych regionach świata. Taka prezentacja to podkreślenie uniwersalnego charakteru chleba jako pożywienia, który w znanej czy nieznanej nam dotychczas innej formie można znaleźć w każdym zakątku kuli ziemskiej zamieszkałym przez ludzi. Odkąd istnieje pismo, wzmiankowano na temat chleba, toteż, dodatkowo, jego kultowa i kulturowo – symboliczna wartość jest nie do przecenienia. Inauguracja FESTIWALU CHLEBÓW ŚWIATA planowana jest w piątek, w dniu 21 marca 2014 roku, pierwszym dniu wiosny a potrwa ona do niedzieli tj. do 23.03. 2014 r.. Uczniowie wówczas szukają pomysłów na nieodbywanie typowych zajęć lekcyjnych. My proponujemy bardzo celowe „vagari”- zapraszając uczniów wszystkich typów i poziomów szkoły z opiekunami do spotkania się na Festiwalu. -

@Cafehushhush 15170 Bangy Rd, Lake Oswego, Or 97035

(503) 274-1888 @CAFEHUSHHUSH 15170 BANGY RD, LAKE OSWEGO, OR 97035 WWW.HUSHHUSHMEDITERRANEANCUISINE.COM AUTHENTIC LEBANESE AND MEDITERRANEAN CUISINE APPETIZERS Served with fresh homemade pita bread. Extra bread $1.00 Substitute bread for veggies (GF) Our Kibbeh H ummus (V, GF) $7.50 Hummus Beiruti Style (V,GF) $9.95 A delightful dip of pureed garbanzo beans, blended with tahini, & A spicy version of our hummus, A delightful dip of pureed garbanzo lemon. Topped with extra virgin olive oil. beans, bleneded with tahini & lemon. Topped with extra virgin olive * Add a topping of your choice of meat: Gyro(H) or Chicken(H) +$4.00 oil. Baba Ghanouj (V, GF) $7.50 Falafel Plate (V, GF) $7.50 Charcoal broiled eggplant with a great smoky flavor, blended with Crispy, warm & delicious homemade chickpea veggie patties. Mixed lemon & tahini. Topped with extra virgin olive oil. with chopped parsley, onions, and garlic. Served with a side of tahini sauce. Labneh (GF) $7.50 Makdous (V) $7.50 Creamy cheese dip, made of middle Eastern strained Pickled baby eggplants, stuffed with walnuts, jalapeño, parsley, and yogurt. garnished with mint, and extra virgin olive oil. garlic. Topped with extra virgin olive oil. Ful Medames (V, GF) $7.50 Kibbeh (3pcs) $9.95 A hearty dip of fava beans simmered until tender, and flavored Tasty stuffed wheat balls, fried light and crispy, served warm, made with garlic, lemon and olive oil. from bulgar wheat dough and filled with ground beef, onions, nuts, and spices. Served with tzatziki sauce. (NO bread) Sambousek (3pcs) (H) $7.50 Warm, crispy stuffed pastries.