No Greens in the Forest?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alphabetical Lists of the Vascular Plant Families with Their Phylogenetic

Colligo 2 (1) : 3-10 BOTANIQUE Alphabetical lists of the vascular plant families with their phylogenetic classification numbers Listes alphabétiques des familles de plantes vasculaires avec leurs numéros de classement phylogénétique FRÉDÉRIC DANET* *Mairie de Lyon, Espaces verts, Jardin botanique, Herbier, 69205 Lyon cedex 01, France - [email protected] Citation : Danet F., 2019. Alphabetical lists of the vascular plant families with their phylogenetic classification numbers. Colligo, 2(1) : 3- 10. https://perma.cc/2WFD-A2A7 KEY-WORDS Angiosperms family arrangement Summary: This paper provides, for herbarium cura- Gymnosperms Classification tors, the alphabetical lists of the recognized families Pteridophytes APG system in pteridophytes, gymnosperms and angiosperms Ferns PPG system with their phylogenetic classification numbers. Lycophytes phylogeny Herbarium MOTS-CLÉS Angiospermes rangement des familles Résumé : Cet article produit, pour les conservateurs Gymnospermes Classification d’herbier, les listes alphabétiques des familles recon- Ptéridophytes système APG nues pour les ptéridophytes, les gymnospermes et Fougères système PPG les angiospermes avec leurs numéros de classement Lycophytes phylogénie phylogénétique. Herbier Introduction These alphabetical lists have been established for the systems of A.-L de Jussieu, A.-P. de Can- The organization of herbarium collections con- dolle, Bentham & Hooker, etc. that are still used sists in arranging the specimens logically to in the management of historical herbaria find and reclassify them easily in the appro- whose original classification is voluntarily pre- priate storage units. In the vascular plant col- served. lections, commonly used methods are systema- Recent classification systems based on molecu- tic classification, alphabetical classification, or lar phylogenies have developed, and herbaria combinations of both. -

Principi Di Spontaneizzazione in Sicilia Di Talinum Paniculatum (Talinaceae)

Quad. Bot. Amb. Appl. 26 (2015): 23-26. Pubblicato online il 28.07.2017 Principi di spontaneizzazione in Sicilia di Talinum paniculatum (Talinaceae) F. SCAFIDI & F.M. RAIMONDO Dipartimento STEBICEF/ Sezione di Botanica ed Ecologia vegetale, Via Archirafi 38, I-90123 Palermo. ABSTRACT. – Record of Talinum paniculatum (Talinaceae) naturalized in Sicily. – The record in the urban context of Palermo (Sicily) of Talinum paniculatum, species native to Tropical America and mainly cultivated for ornamental purposes, is reported. It is the first case of naturalization in the Island of a species of Talinaceae family introduced to Palermo in 1984 from Argentina and cultivated in the Botanical Garden collections. Key words: Talinum, alien flora, Mediterranean plants, Sicily. PREMESSA Il genere Talinum Adans. (Talinaceae) comprende circa 1984, assieme ad altro materiale vivo raccolto nel corso della 50 specie distribuite principalmente nelle regioni tropicali e escursione post congresso, organizzata in quel paese dalla subtropicali di entrambi gli emisferi, con centri di diversità IAVS. Subito dopo il suo inserimento nelle collezioni in vaso nelle regioni tropicali delle Americhe e in Sud Africa dell’Orto, all’interno del giardino, nelle aiuole e nei vasi da (MABBERLEY, 2008). Le specie riferite a questo genere – in collezione, cominciarono ad osservarsi diversi individui precedenza incluso nella famiglia Portulacaceae – sono per spontanei, indice di un’attiva capacità di spontaneizzazione lo più erbe e si distinguono per avere fusto e foglie succulenti della specie nel peculiare clima della Città di Palermo, (MENDOZA & WOOD, 2013). Tra di esse figura Talinum contesto in cui la specie non risulta essere ancora coltivata. paniculatum (Jacq.) Gaertn., taxon originario dell’America tropicale, oggi considerato infestante pantropicale. -

A Comparative Study on in Vitroantibacterial Activity Of

Human Journals Research Article October 2017 Vol.:10, Issue:3 © All rights are reserved by K.D.K.P. Kumari et al. A Comparative Study on In Vitro Antibacterial Activity of Different Leaf Extracts of Medicinal Plant Talinum paniculatum Keywords: Talinum paniculatum, leaf extracts, antibacterial activity, in vitro ABSTRACT R.N.N. Gamage, K.B. Hasanthi, K.D.K.P. Kumari* There is an urgent need for the development of novel affordable plant based natural antibacterial agents in order to combat Department of Basic Sciences, Faculty of Allied Health against the emergence of antibiotic resistance, resulting from Sciences, General Sir John Kotelawala Defence the indiscriminate use of currently available antibiotics. Therefore, this study evaluated the in vitro antibacterial activity University, Ratmalana, Sri Lanka and minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of aqueous, methanol, acetone and hexane extracts of the leaf Talinum Submission: 22 September 2017 paniculatum against Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) and Accepted: 3 October 2017 Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923). Agar well diffusion Published: 30 October 2017 method was performed to evaluate antibacterial activity of each leaf extract at concentrations of 100 mg/mL and 50 mg/mL. Additionally, broth dilution technique was used to determine MIC. The results revealed, for the first time, that each crude leaf extract exhibited antibacterial activity against both E. coli and S. aureus. The largest zones of inhibition against E. coli and S. aureus were observed for 100 mg/mL methanolic and www.ijppr.humanjournals.com aqueous leaf extracts, respectively. It is concluded that antibacterial potential of the leaf T. paniculatum is mediated primarily via its phytoconstituents, such as alkaloids, phenols, saponins, tannins, steroids, triterpenes and flavonoids. -

Full of Beans: a Study on the Alignment of Two Flowering Plants Classification Systems

Full of beans: a study on the alignment of two flowering plants classification systems Yi-Yun Cheng and Bertram Ludäscher School of Information Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA {yiyunyc2,ludaesch}@illinois.edu Abstract. Advancements in technologies such as DNA analysis have given rise to new ways in organizing organisms in biodiversity classification systems. In this paper, we examine the feasibility of aligning two classification systems for flowering plants using a logic-based, Region Connection Calculus (RCC-5) ap- proach. The older “Cronquist system” (1981) classifies plants using their mor- phological features, while the more recent Angiosperm Phylogeny Group IV (APG IV) (2016) system classifies based on many new methods including ge- nome-level analysis. In our approach, we align pairwise concepts X and Y from two taxonomies using five basic set relations: congruence (X=Y), inclusion (X>Y), inverse inclusion (X<Y), overlap (X><Y), and disjointness (X!Y). With some of the RCC-5 relationships among the Fabaceae family (beans family) and the Sapindaceae family (maple family) uncertain, we anticipate that the merging of the two classification systems will lead to numerous merged solutions, so- called possible worlds. Our research demonstrates how logic-based alignment with ambiguities can lead to multiple merged solutions, which would not have been feasible when aligning taxonomies, classifications, or other knowledge or- ganization systems (KOS) manually. We believe that this work can introduce a novel approach for aligning KOS, where merged possible worlds can serve as a minimum viable product for engaging domain experts in the loop. Keywords: taxonomy alignment, KOS alignment, interoperability 1 Introduction With the advent of large-scale technologies and datasets, it has become increasingly difficult to organize information using a stable unitary classification scheme over time. -

Portulacaceae – Purslane Family

PORTULACACEAE – PURSLANE FAMILY Plant: herbs, rarely shrubs Stem: usually fleshy or succulent Root: Leaves: simple, entire, opposite or alternate, or in basal rosettes; stipules mostly absent, may be represented by fleshy structures or modified into hairs Flowers: perfect; 2 sepals usually, rarely up to 9; 2-4-6 or > petals, united or separate at base; stamens usually opposite each petal, or more numerous in a bundle; ovary mostly superior or partially inferior, few to many ovules Fruit: capsule Other: mostly in southern hemisphere; Dicotyledons Group Genera: 30+ genera; locally Claytonia (spring-beauty), Montia, Portulaca, Talinum WARNING – family descriptions are only a layman’s guide and should not be used as definitive Flower Morphology in the 2 or more sepals, 4-6 (rarely more, often Portulacaceae (Purslane Family) 5) free petals, leaves simple and entire, no stipules; stem often succulent Examples of common genera Shoreline Seapurslane [Virginia] Spring-Beauty Sesuvium portulacastrum (L.) L. Claytonia virginica L. var. virginica Purslane [Little Hog Weed] Portulaca oleracea L. (Introduced) Largeflower Fameflower [Rock Pink] Phemeranthus calycinus (Engelm.) Kiger Kiss Me Quick Portulaca pilosa L. PORTULACACEAE – PURSLANE FAMILY Ozark [Wide-Leafed] Spring-Beauty; Claytonia ozarkensis Miller & Chambers [Virginia] Spring-Beauty; Claytonia virginica L. var. virginica Largeflower Fameflower [Rock Pink]; Phemeranthus calycinus (Engelm.) Kiger Purslane [Little Hog Weed] Portulaca oleracea L. (Introduced) Kiss Me Quick; Portulaca pilosa -

Stalactite Development in the Exotesta Cell Walls of Amaranthus Retroflexus L

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Wulfenia Jahr/Year: 2015 Band/Volume: 22 Autor(en)/Author(s): Dzhalilova Khalima K., Timonin Alexander C., Veselova Tatiana D. Artikel/Article: Stalactite development in the exotesta cell walls of Amaranthus retroflexus L. (Amaranthaceae): an unusual way of cell wall lysis 113-125 © Landesmuseum für Kärnten; download www.landesmuseum.ktn.gv.at/wulfenia; www.zobodat.at Wulfenia 22 (2015): 113 –125 Mitteilungen des Kärntner Botanikzentrums Klagenfurt Stalactite development in the exotesta cell walls of Amaranthus retroflexus L. (Amaranthaceae): an unusual way of cell wall lysis Khalima Kh. Dzhalilova, Alexander C. Timonin & Tatiana D. Veselova Summary: The stalactites, unique structures that are specific for Amaranthaceae s. lat., are numerous cross-walled, smooth-contoured masses of precipitated tannic substances in the thickened outer cell wall of the exotesta cells. The stalactites strikingly differ from typical depositions of tannic and other non-crystalline substances in plant cell walls. The latter, unlike stalactites, are deposited in layers parallel to the cell wall or they evenly or gradually impregnate the cell wall. The stalactites are initially detected as isolated, closed, smooth-walled, globular cavities in the inner papillae of the cell wall at the heart embryo developmental stage. These cavities elongate inwards during cell wall differentiation and thickening. They are filled with insoluble tannic substances at the immature seed developmental stage. The stalactites are solid masses of tannic (and phytomelanin) substances, which fill pre-developed cross-walled cavities in the outer cell wall of the exotesta cells. These cavities are completely isolated by the cell wall layers from the plasma membrane at each stage of their development. -

Acmella Oleracea Extract for Oral Mucosa Topical Anesthesia

RESEARCH ARTICLE Development and Evaluation of a Novel Mucoadhesive Film Containing Acmella oleracea Extract for Oral Mucosa Topical Anesthesia Verônica Santana de Freitas-Blanco1,2, Michelle Franz-Montan1, Francisco Carlos Groppo1, João Ernesto de Carvalho1,2,3, Glyn Mara Figueira2, Luciano Serpe1, Ilza Maria Oliveira Sousa2, Viviane Aparecida Guilherme Damasio4, Lais Thiemi Yamane2, 4 1,2 a11111 Eneida de Paula , Rodney Alexandre Ferreira Rodrigues * 1 Department of Physiological Sciences, Piracicaba Dental School, University of Campinas, Piracicaba, Brazil, 2 Chemical, Biological and Agricultural Research Center (CPQBA), University of Campinas, Paulinia, Brazil, 3 Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil, 4 Departmentof Biochemistry and Tissue Biology, Institute of Biology, University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Citation: Santana de Freitas-Blanco V, Franz- Montan M, Groppo FC, de Carvalho JE, Figueira GM, Abstract Serpe L, et al. (2016) Development and Evaluation of a Novel Mucoadhesive Film Containing Acmella oleracea Extract for Oral Mucosa Topical Anesthesia. Purpose PLoS ONE 11(9): e0162850. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0162850 To develop an anesthetic mucoadhesive film containing Acmella oleracea (jambu) extract for topical use on oral mucosa. Editor: Charlene S. Dezzutti, University of Pittsburgh, UNITED STATES Received: April 12, 2016 Methods Accepted: August 28, 2016 Ethanolic extracts from aerial parts of jambu were prepared by maceration. Pigment Published: September 14, 2016 removal was obtained by adsorption with activated carbon. Three mucoadhesive films were developed using a film casting method: 10 or 20% of crude jambu extract (10% JB and 20% Copyright: © 2016 Santana de Freitas-Blanco et al. This is an open access article distributed under the JB), and 10% of crude jambu extract treated with activated carbon (10% JBC). -

Grow Your Own Remedies

Grow Your Own Remedies Herbalist Tish Streeten | [email protected] | 518-461-3631 queenmabscsm.com | mabfilms.org Plant Meditation Happy Birthday Dor Deb Soule’s Advice Laugh & dance, sing & pray in your garden Gertrude Jekyll’s Advice Use colour Mary Reynold’s Advice Change is the breath of life Why Grow Your Own Healing Begins in the Garden • For your & your family’s health • Always there, never run out • For gut health • For spiritual & emotional health • For bees and pollinators • Keep unwanted bugs away • Health of other plants • Animal health • For survival • For beauty • For the soil How I Garden - Haphazardly! •Easy •Trial & error •What grows well where i am •Perennials •Always comfrey, borage, tulsi, wormwood, calendula, lemon balm •Spilanthes, gotu kola, feverfew, chrysanthemum •artichoke, elecampane, blessed thistle Culinary & Medicinal Herbs •Rosemary •Thyme •Sage •Oregano •Basil •Mints •Parsley •Cilantro Easy Plants to Grow Something for everyone & every ailment Plants that keep giving •Elder - Sambucus nigra •Nasturtium - Tropaeolum minor •Anise Hyssop - Agastache foeniculum •Rose - Rosa spp. • Bee Balm - Monarda spp. •Poppy - Papaver spp. •Comfrey - Symphytum officinale •Wormwood - Artemisia absinthium •Lemon Balm - Melissa officinalis •Borage - Borago officinalis •Tulsi - Ocimum sanctum/tenufloram •Hummingbird Sage - Salvia spathacea •Chamomile - Matricaria recutita •Sage - Salvia spp. •Calendula - Calendula officinalis •Geranium - Pelargonium •Lady’s Mantle - Alchemilla vulgaris •Echinacea - Echinacea spp. •Fennel - Foeniculum -

Synopsis of a New Taxonomic Synthesis Of

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 8 October 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201808.0496.v2 Hershkovitz Montiaceae Synopsis of a new taxonomic synthesis of Montiaceae (Portulacineae) based on rational metadata analysis, with critical new insights on historically poorly understood taxa and a review of ecological evolution and phylogeography Mark Alan HERSHKOVITZ1 1Santiago, Chile [email protected] Abstract: Montiaceae (Portulacineae) comprise a clade of at least 280 species and ca. 30 subspecific taxa primarily of western America and Australia. This work uses existing phylogenetic metadata to elaborate a new cladistic taxonomic synthesis, and clarifies morphological circumscriptions of several poorly known species. A total of 20 taxa are validated, seven new and 13 necessary nomenclatural recombinations. Hypotheses of Montiaceae historical biogeography and phenotypic evolution are evaluated in light of recent metadata. Key words: Montiaceae, taxonomy, phylogeny, ecology, phylogeography, evolution. 1. Introduction This work presents a new cladistic taxonomy of Montiaceae (Portulacineae) and several of its included taxa, along with notes on the diagnostics of certainly poorly known species and a summary of new interpretations of phylogeography and phenotypic and ecological evolution. The present work includes 20 nomenclatural novelties. However, the whole of the novelty is greater than the sum of these parts. The generic circumscriptions and diversity estimates are modified from Hernández-Ledesma et al. (2015).The suprageneric taxonomy is the first proposed since McNeill (1974) and the only phylogenetic one. Critical reevaluation of certain common and usually misidentified Chilean taxa is the first since Reiche (1898). Existing metadata are interpreted as evidence for a hybrid origin of a genus. -

Gardenergardener®

Theh American A n GARDENERGARDENER® The Magazine of the AAmerican Horticultural Societyy January / February 2016 New Plants for 2016 Broadleaved Evergreens for Small Gardens The Dwarf Tomato Project Grow Your Own Gourmet Mushrooms contents Volume 95, Number 1 . January / February 2016 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 5 NOTES FROM RIVER FARM 6 MEMBERS’ FORUM 8 NEWS FROM THE AHS 2016 Seed Exchange catalog now available, upcoming travel destinations, registration open for America in Bloom beautifi cation contest, 70th annual Colonial Williamsburg Garden Symposium in April. 11 AHS MEMBERS MAKING A DIFFERENCE Dale Sievert. 40 HOMEGROWN HARVEST Love those leeks! page 400 42 GARDEN SOLUTIONS Understanding mycorrhizal fungi. BOOK REVIEWS page 18 44 The Seed Garden and Rescuing Eden. Special focus: Wild 12 NEW PLANTS FOR 2016 BY CHARLOTTE GERMANE gardening. From annuals and perennials to shrubs, vines, and vegetables, see which of this year’s introductions are worth trying in your garden. 46 GARDENER’S NOTEBOOK Link discovered between soil fungi and monarch 18 THE DWARF TOMATO PROJECT BY CRAIG LEHOULLIER butterfl y health, stinky A worldwide collaborative breeds diminutive plants that produce seeds trick dung beetles into dispersal role, regular-size, fl avorful tomatoes. Mt. Cuba tickseed trial results, researchers unravel how plants can survive extreme drought, grant for nascent public garden in 24 BEST SMALL BROADLEAVED EVERGREENS Delaware, Lady Bird Johnson Wildfl ower BY ANDREW BUNTING Center selects new president and CEO. These small to mid-size selections make a big impact in modest landscapes. 50 GREEN GARAGE Seed-starting products. 30 WEESIE SMITH BY ALLEN BUSH 52 TRAVELER’S GUIDE TO GARDENS Alabama gardener Weesie Smith championed pagepage 3030 Quarryhill Botanical Garden, California. -

Bring a Wagon!

NEW ORLEANS BOTANICAL GARDEN PELICAN GREENHOUSE SALE March 14, 2020 9 am – NOON Greenhouse is located just off Henry Thomas (Golf) Drive south of the I 610 underpass, Google Maps Address – 2 Celebration Drive Bring a wagon! Calendula officinalis Calendula Concrete Benches Cladanthus arabicus Palm Springs Daisy Concrete Benches Euphorbia ‘Diamond Frost’ Diamond Frost Euphorbia Concrete Benches HERB Anethum graveolens Teddy Dill Concrete Benches HERB Carum carvi Caraway Concrete Benches HERB Coriandrum sativum ‘Calypso’ Calypso Cilantro Concrete Benches HERB Foeniculum vulgare ‘Rubrum’ Bronze Fennel Concrete Benches HERB Nepeta cataria Catnip Concrete Benches HERB Ocimum basilicum ‘Genovese’ Genovese Large Leaf Basil Concrete Benches HERB Petroselinum crispum Flat Leaf Parsley Concrete Benches HERB Petroselinum crispum ‘Darki’ Curly Leaf Parsley Concrete Benches HERB Thymus vulgaris German Winter Thyme Concrete Benches Lavendula stoechas ‘Bandera Pink’ Lavender Concrete Benches Nasturtium ‘Jewel Mix’ Jewel Mix Nasturtium Concrete Benches Nemesia ‘Masquerade’ Masquerade Nemesia Concrete Benches Osteospermum ecklonis ‘Zion Copper Amethyst’ African Daisy Concrete Benches Sisyrinchium angustifolium ‘Lucerne’ Lucerne Blue Eyed Grass Concrete Benches SQUASH Cucurbita pepo Crookneck Yellow Squash Concrete Benches SQUASH Cucurbita pepo Tempest Squash Concrete Benches VEGETABLE Beta vulgaris ‘Bright Lights’ Bright Lights Swiss Chard Concrete Benches VEGETABLE Cucurbita pepo Raven Zucchini Concrete Benches VEGETABLE Physalis philadelphica Toma Verde -

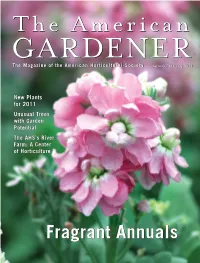

Fragrant Annuals Fragrant Annuals

TheThe AmericanAmerican GARDENERGARDENER® TheThe MagazineMagazine ofof thethe AAmericanmerican HorticulturalHorticultural SocietySociety JanuaryJanuary // FebruaryFebruary 20112011 New Plants for 2011 Unusual Trees with Garden Potential The AHS’s River Farm: A Center of Horticulture Fragrant Annuals Legacies assume many forms hether making estate plans, considering W year-end giving, honoring a loved one or planting a tree, the legacies of tomorrow are created today. Please remember the American Horticultural Society when making your estate and charitable giving plans. Together we can leave a legacy of a greener, healthier, more beautiful America. For more information on including the AHS in your estate planning and charitable giving, or to make a gift to honor or remember a loved one, please contact Courtney Capstack at (703) 768-5700 ext. 127. Making America a Nation of Gardeners, a Land of Gardens contents Volume 90, Number 1 . January / February 2011 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 5 NOTES FROM RIVER FARM 6 MEMBERS’ FORUM 8 NEWS FROM THE AHS 2011 Seed Exchange catalog online for AHS members, new AHS Travel Study Program destinations, AHS forms partnership with Northeast garden symposium, registration open for 10th annual America in Bloom Contest, 2011 EPCOT International Flower & Garden Festival, Colonial Williamsburg Garden Symposium, TGOA-MGCA garden photography competition opens. 40 GARDEN SOLUTIONS Plant expert Scott Aker offers a holistic approach to solving common problems. 42 HOMEGROWN HARVEST page 28 Easy-to-grow parsley. 44 GARDENER’S NOTEBOOK Enlightened ways to NEW PLANTS FOR 2011 BY JANE BERGER 12 control powdery mildew, Edible, compact, upright, and colorful are the themes of this beating bugs with plant year’s new plant introductions.