Czech Law in Historical Contexts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Material Culture and Daily Life in the New City of Prague, 1547-1611

MATERIAL CULTURE AND DAILY LIFE IN THE NEW CITY OF PRAGUE IN THE AGE OF RUDOLF II MEDIUM AEVUM QUOTIDIANUM HERAUSGEGEBEN VON GERHARD JARITZ SONDERBAND VI James R. Palmitessa MATERIAL CULTURE & DAILY LIFE IN THE NEW CITY OF PRAGUE IN THE AGE OF RUDOLF II KREMS 1997 GEDRUCKT MIT UNTERSTÜTZUNG DER KULTURABTEILUNG DES AMTES DER NIEDERÖSTERREICHISCHEN LANDESREGIERUNG Cover illustration: Detail of the New City of Prague from the Sadeler engraving of 1606. The nine-part copper etching measuring 47.6 x 314 cm. is one of the largest of any city in its day. It was a cooperative project of a three-person team belonging to the !arge and sophisticated group of artists at the court of Emperor Rudolf II in Prague. Aegidius Sadeler, the imperial engraver, commissioned the project and printed the copper-etching which was executed by Johannes Wechter after drawings by Philip van den Bosche. In the center of the illustration are the ruins of the Church and Cloister of Mary of the Snow (item no. 84). The broad thoroughfare Na pfikope (•im Graben�), item no. 83, separates the Old City (to the left) from the New City (to the right). To the right of the Church and Cloister of Mary of the Snow is the long Horse Market (today Wenceslaus Square), item no. 88. The New City parish church Sv. Jind.ficha (St. Henry) can be located just above the church and cloister (item no. 87). -ISBN 3-901094 09 1 Herausgeber: Medium Aevum Quotidianum. Gesellschaft zur Erforschung der materiellen Kultur des Mittelalters. Körnermarkt 13, A-3500 Krems, Österreich. -

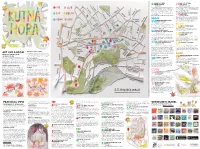

Act Like a Local See Eat Practical Info Drink Relax Shop

HAVE YOU EVER BAR OUT OF TIME 14 BEEN A HIPPIE? 21AND SPACE Jakubská 562 Komenského nám. 39/19 Have you ever gone through a hippie phase in your life? Blues Having a hard time coming up with an idea of how to describe café will definitely take you back there. An endless stock of this place, we assume No Name is really an appropriate name rock’n’roll and bluesy LP’s, your favourite 60s heroes on the for this bar. Anyway, it’s a local favorite for its friendly person- walls and a long haired barkeeper who is a relentless critic of nel, cheap drinks and table football. current politics and society. If you’re lucky you’ll meet local Sun–Thu 18–23, Fri–Sat 18–03 jazz musicians jamming there. If not, at least you can have a quiche, a baguette or a bowl of hot soup while listening to LOCAL CLASSIC WITH STEAM some John Mayall. 22PUNK VIBES Mon 10–19, Tue–Thu 9–19, Fri–Sat 10–22, Sun 11:30–18 Havlíčkovo nám. 552 Whenever we go to the Pod schodama pub, we’ll find some of our friends playing table football or singing along to the DRINK jukebox. Usually open till late night hours, this rusty dive bar is a stronghold for Kutná Hora’s youth, a witness to all the A MEDITATIVE REFUGE FOR important plot twists in our lives. Mon–Sun 18–03 15FANTASY LOVERS Havlíčkovo nám. 84 This shisha scented tea room is a meditative refuge for fanta- RELAX sy lovers. -

Pecunia Omnes Vincit

PECUNIA OMNES VINCIT Pecunia Omnes Vincit COIN AS A MEDIUM OF EXCHANGE THROUGHOUT CENTURIES ConfErEnCE ProceedingS OF THE THIRD INTERNATIONAL numiSmatiC ConfErEnCE KraKow, 20-21 may 2016 Edited by Barbara Zając, Paulina Koczwara, Szymon Jellonek Krakow 2018 Editors Barbara Zając Paulina Koczwara Szymon Jellonek Scientific mentoring Dr hab. Jarosław Bodzek Reviewers Prof. Dr hab. Katarzyna Balbuza Dr hab. Jarosław Bodzek Dr Arkadiusz Dymowski Dr Kamil Kopij Dr Piotr Jaworski Dr Dariusz Niemiec Dr Krzysztof Jarzęcki Proofreading Editing Perfection DTP GroupMedia Project of cover design Adrian Gajda, photo a flan mould from archive Paphos Agora Project (www.paphos-agora.archeo.uj.edu.pl/); Bodzek J. New finds of moulds for cast- ing coin flans at the Paphos agora. In. M. Caccamo Caltabiano et al. (eds.), XV Inter- national Numismatic Congress Taormina 2015. Proceedings. Taormina 2017: 463-466. © Copyright by Adrian Gajda and Editors; photo Paphos Agora Project Funding by Financial support of the Foundation of the Students of the Jagiellonian University „BRATNIAK” © Copyright by Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University Krakow 2018 ISBN: 978-83-939189-7-3 Address Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University 11 Gołębia Street 31-007 Krakow Contents Introduction /7 Paulina Koczwara Imitations of Massalian bronzes and circulation of small change in Pompeii /9 Antonino Crisà Reconsidering the Calvatone Hoard 1942: A numismatic case study of the Roman vicus of Bedriacum (Cremona, Italy) /18 Michał Gębczyński Propaganda of the animal depictions on Lydian and Greek coins /32 Szymon Jellonek The foundation scene on Roman colonial coins /60 Barbara Zając Who, why, and when? Pseudo-autonomous coins of Bithynia and Pontus dated to the beginning of the second century AD /75 Justyna Rosowska Real property transactions among citizens of Krakow in the fourteenth century: Some preliminary issues /92 Introduction We would like to present six articles by young researchers from Poland and Great Britain concerning particular aspects of numismatics. -

Sigismund of Luxembourg's Pledgings in Hungary

DOI: 10.14754/CEU.2018.10 Doctoral Dissertation “Our Lord the King Looks for Money in Every Corner” Sigismund of Luxembourg’s Pledgings in Hungary By: János Incze Supervisor(s): Katalin Szende, Balázs Nagy Submitted to the Medieval Studies Department, and the Doctoral School of History Central European University, Budapest in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Medieval Studies, and for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2018 DOI: 10.14754/CEU.2018.10 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1. Pledging and Borrowing in Late Medieval Monarchies: an Overview ......................... 9 Western Europe ......................................................................................................................... 11 Central Europe and Scandinavia ............................................................................................... 16 Chapter 2. The Price of Ascending to the Throne ........................................................................ 26 Preceding events ....................................................................................................................... 26 The Váh-Danube interfluve under Moravian rule .................................................................... 29 Regaining the territory ............................................................................................................. -

Get to Know the Story of Henry and the History of Bohemia Posázaví in the Middle Ages the SÁZAVA / SASAU REGION to Begin At

Not for sale for Not 1. edition 1. Prague 6/2018 Prague Photo and text: Warhorse Studios, SCCR Studios, Warhorse text: and Photo © Central Bohemia Turist Board Turist Bohemia Central © @visitcentralbohemia FB/centralbohemia of today. of is open our map and set off, exploring the Posázaví Posázaví the exploring off, set and map our open is recounted, changed over time? All you need to do do to need you All time? over changed recounted, sometimes harsh reality. harsh sometimes So, how much have these medieval locations, as as locations, medieval these have much how So, comparing their medieval appearance to today’s today’s to appearance medieval their comparing a sightseeing trail of the key locations, also also locations, key the of trail sightseeing a beautiful landscapes. beautiful To help explore more easily, we bring you you bring we easily, more explore help To own eyes the impressive local architecture and and architecture local impressive the eyes own Henry’s wanderings, to see and explore with their their with explore and see to wanderings, Henry’s doubt keen to see them with your own eyes. own your with them see to keen doubt become a popular destination for followers of of followers for destination popular a become may not have heard of, but since KCD you are no no are you KCD since but of, heard have not may The Posázaví region, where the story is set, has has set, is story the where region, Posázaví The (Rattay), Talmberk (Talmberg) … places you may or or may you places … (Talmberg) Talmberk (Rattay), whole villages and towns; Sázava (Sasau), Rataje Rataje (Sasau), Sázava towns; and villages whole right around the world. -

Section II: Summary of the Periodic Report on the State of Conservation

State of Conservation of World Heritage Properties in Europe SECTION II Hora is the result of a complex evolution, in terms of both urban development and architecture. With CZECH REPUBLIC its boundaries clearly demarcated, the town’s setting in the surrounding landscape results in an exceptional appeal of the historical centre’s Kutna Hora: Historical Town panorama. The Sedlec Cathedral, the oldest in Centre with the Church of St Bohemia, is an architectural treasure located on the Barbara and the Cathedral of Our grounds of the former monastery. Lady at Sedlec (i) Reasons for which the property is considered to meet one or more criteria posed on world heritage: Brief description Re Article 24 para (i) of the UNESCO directives, the Kutná Hora developed as a result of the exploitation historical town of Kutná Hora was during the of the silver mines. In the 14th century it became a mediaeval period, from the early 14th century to the royal city endowed with monuments that first third of the 16th century, after Prague the symbolized its prosperity. The Church of St second most important centre of the Kingdom of Barbara, a jewel of the late Gothic period, and the Bohemia. This is apparent still today in the town’s Cathedral of Our Lady at Sedlec, which was exceptional wealth of historical architecture, restored in line with the Baroque taste of the early beginning with specimens of the Gothic style. The 18th century, were to influence the architecture of town’s ground plan attests to complex evolution. Its central Europe. These masterpieces today form agglomeration of architectures covering a wide part of a well-preserved medieval urban fabric with variety of types and styles forms an exceptionally some particularly fine private dwellings. -

Did Silesia Constitute an Economic Region Between the 13Th and the 15Th Centuries? a Survey of Region-Integrating and Region-Disintegrating Economic Factors

Grzegorz Myśliwski University of Warsaw Did Silesia constitute an economic region between the 13th and the 15th centuries? A survey of region-integrating and region-disintegrating economic factors Abstract: This article constitutes an attempt at answering the question of whether Silesia, aside from being a distinct historical region, was also a distinct economic region. The author starts with Robert E. Dickinson’s theory of economic regions, the basic assumptions of which are shared by contempo- rary researchers of regional economies. Economic resources, the similar economic policies of Silesian rulers in the 13th and 14th centuries, high levels of urbanization in comparison to neighbouring regions and the centralizing capacity of Wrocław are considered to be the forces which bound together Silesian as an economic region. Factors retard- ing the economic cohesion of Silesia were analyzed as well. Those included natural disasters, inva- sions, internal strife, criminal activity along trade routes and a crisis in the mining industry beginning in the middle of the 14th century. Beginning with the final years of the 13th century, Silesia stabilized as an economic region containing Upper Silesia, Lower Silesia and Opava. This was not, however, a perfect cohesion, as Lower Silesia was economically superior to the other regions, which themselves had strong ties to Lesser Poland. Despite that, the crisis that took place from about 1350 until 1450 did not break the economic bonds between these three constituent elements of Silesia. In comparison to every historical and economic region on its borders, Silesia was distinguished by its advanced gold mining industry, the export of a red dyeing agent (marzanna) as well as the highest number of cities with a populations of between 3,000 and 14,000. -

Vol. 18 2013 Vol. 18 2013 KINGS IN

www.vistulana.pl 2013 www.qman.com.pl 18 vol. vol. vol. 18 2013 KINGS IN CAPTIVITY MACROECONOMY: ECONOMIC GROWTH ISBN 978-83-61033-69-1 KINGS IN CAPTIVITY MACROECONOMY: ECONOMIC GROWTH Fundacja Centrum Badań Historycznych Warszawa 2013 QUAESTIONES MEDII AEVI NOVAE Journal edited by Wojciech Fałkowski (Warsaw) – Editor in Chief Marek Derwich (Wrocław) Tomasz Jasiński (Poznań) Krzysztof Ożóg (Cracow) Andrzej Radzimiński (Toruń) Paweł Derecki (Warsaw) – Assistant Editor Editorial Board Gerd Althoff (Münster) Philippe Buc (Wien) Patrick Geary (Princeton) Andrey Karpov (Moscow) Rosamond McKit erick (Cambridge) Yves Sassier (Paris) Journal accepted in the ERIH and Index Copernicus lists. Articles, Notes and Books for Review shoud be sent to: Quaestiones Medii Aevi Novae, Instytut Historyczny Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego; Krakowskie Przedmieście 26/28, PL 00-927 Warszawa; Tel./Fax: (0048 22) 826 19 88; [email protected] (Editor in Chief) Published and fi nanced by: • Institute of History of University of Warsaw • Nicolas Copernicus University in Toruń • Faculty of History of University of Poznań • Institute of History of Jagiellonian University of Cracow • Ministry of Science and Higher Education © Copyright by Center of Historical Research Foundation, 2013 ISSN 1427-4418 ISBN 978-83-61033-69-1 Printed in Poland Subscriptions: Published in December. The annual subscriptions rate 2013 is: in Poland 38,00 zł; in Europe 32 EUR; in overseas countries 42 EUR Subscriptions orders shoud be addressed to: Wydawnictwo Towarzystwa Naukowego “Societas Vistulana” ul. Garczyńskiego 10/2, PL 31-524 Kraków; E-mail: [email protected]; www.vistulana.pl Account: Deutsche Bank 24 SA, O/Kraków, pl. Szczepański 5 55 1910 1048 4003 0092 1121 0002 Impression 550 spec. -

Explore Europe

Trail Blazer Tours India Pvt. Ltd Tel: +91 22 61940940 [email protected] World Trade Centre Complex, Fax: +91 22 61940900 www.trailblazertours.com 902, Centre 1, Cuffe Parade, Mumbai—400005. 1 INDEX Northern Europe Western Europe Southern Europe Eastern Europe United Kingdom 3 Austria 27 Greece 65 Czech Republic, Ireland 9 Benelux 35 Italy 69 Hungary & Poland 97 Scandinavia 15 France 41 Malta 75 Russian Federation 103 Iceland 23 Germany 47 Spain & Portugal 79 Switzerland 55 Slovenia & Croatia 85 TBi Branch Addresses 108 Turkey 91 2 3 about TBi TBi - your Trail Blazer Tours India Pvt. Ltd. was established in 2007 by travel guide industry professionals and taken over in 2010 by the well known Katgara Group, pioneers in tourism, setting new standards of to Europe innovation and excellence. Our core services include inbound tourism, corporate travel, conferences, incentives, domestic and Welcome to TBi’s world United international holidays. With over 250 experienced professionals of carefree, memorable at offices in major cities, we offer quality services at the best holidays in Europe. Choose Northern Europe Kingdom possible price. TBi has won several prestigious awards including from popular destinations the National Tourism Award in recognition of its outstanding or discover lesser known performance. ones, travel on your own or take an escorted tour; see We Believe as much or as little as you The four constituent countries that together form the sovereign • That travel promotes peace and understanding. like. Take a luxury cruise or state of the United Kingdom are England, Northern Ireland, travel all over by rail. TBi • That integrity, innovation and service excellence are crucial Scotland and Wales. -

Tom XV 5 CIECIELĄG 2008: 99–101

THE TEMPLE ON THE COINS OF BAR KOKHBA – A MANIFESTATION OF LONGING… which is undoubtedly an expression of the rebels’ hope and goals, i.e. the rebuilding of the Jerusalem temple, restoration of circumcision and regaining independence, is important. It is worth noting here, however, that perhaps we are not dealing here so much with a political programme, but rather with reconciliation with God and eternal salvation, which would link the revolt of Bar Kokhba with the ideology of the first revolt against the Romans and with the Hasmonean period.4 Equally important, or perhaps even more important, is the inscription referring to Jerusalem (on the coins from the first year of revolt), inseparably connected with Hadrian’s decision to transform the city into a Roman colony under the name Colonia Aelia Capitolina and probably also with the refusal to rebuild the Temple.5 As we are once again dealing here with a manifestation of one of the most important goals of Bar Kokhba and the insurgents – the liberation of Jerusalem and the restoration of worship on the Temple Mount. Even more eloquent is the inscription on coins minted in the third year of the revolt: Freedom of Jerusalem, indicating probably a gradual loss of hope of regaining the capital and chasing the Romans away. Many researchers believed that in the early period of the revolt, Jerusalem was conquered by rebels,6 which is unlikely but cannot be entirely excluded. There was even a hypothesis that Bar Kokhba rebuilt the Temple of Jerusalem, but he had to leave Jerusalem, which he could -

The Origin and History of the Polish Money. Part I Pochodzenie I Historia Polskiego Pieniàdza

BANK I KREDYT listopad-grudzieƒ 2006 On invitation 3 The Origin and History of the Polish Money. Part I Pochodzenie i historia polskiego pieniàdza. Cz´Êç I Grzegorz Wójtowicz* Abstract Streszczenie Poland’s money has a pedigree of over a thousand years. At the Polski pieniàdz ma ponadtysiàcletni rodowód. W koƒcu X wieku end of the 10th century the silver denar began to supplant various srebrny denar zaczà∏ wypieraç ró˝ne towary, które dotychczas commodities that had previously functioned as means of wyst´powa∏y w roli Êrodków p∏atniczych. System denarowy payment. The denar system survived for several centuries. In the przetrwa∏ kilka stuleci. W XIV wieku miejsce denara zajà∏ 14th century, the role of the denar was taken over by the silver srebrny grosz. Koniec XV wieku przyniós∏ narodziny z∏otego grosz. The end of the 15th century witnessed the birth of the polskiego, jako równowartoÊci 30 srebrnych groszy. Poczàtek Polish zloty, taken as equal to 30 silver grosz. The beginnings of dziejowej drogi z∏otego polskiego by∏ obiecujàcy. Z∏oty by∏ the historical path travelled by the Polish zloty were promising. równowartoÊcià z∏otego dukata i srebrnego talara. Potem jednak The zloty corresponded in value to the gold ducat and to the by∏o gorzej. Wraz z kryzysem paƒstwa i gospodarki nast´powa∏ silver thaler. Later, however, things got worse. The crisis of the upadek pieniàdza. Dopiero w koƒcu XVIII wieku moneta state and the economy was accompanied by the decline of the odzyska∏a dobrà jakoÊç. currency. It was not until the end of the 18th century that the Historia monetarna Polski po 1795 r. -

Bohemia & Moravia

BOHEMIA & MORAVIA COAT OF ARMS of BOHEMIA Bohemia, in current Czech Republic Moravia, in current Czech Republic BORIVOJ I 851-888 Borivoj I was Duke of Bohemia (851 - 888). The head of the Premyslid Czechs who dominated the environs of Prague, Borivoj in c. 870 declared himself kníe (later translated by German scholars as 'Duke') of the Czechs (Bohemians). Borivoj was recognised as such by his overlord Svatopluk I of Great Moravia around 872 who dispatched Bishop Methodius to begin the conversion of the Czechs to Christianity. Borivoj and his wife Saint Ludmila were baptised by Methodius in 874 and the latter especial- ly became an enthusiastic evangelist, although the religion failed to take root among Borivoj's subjects. Around 883 Borivoj was deposed by a revolt in support of his kinsman Strojmir, and restored only with the support of Svatopluk of Moravia. As with most of the early Bohemian rulers, Borivoj is a shadowy figure and exact dates and facts for his reign can never be considered as completely reliable, although several major fortifications and religious foundations are said to have dated from this time. In old Czech legends he is said to be son of a prince of Bohemians called Hostivít. SPYTIHNEV I - c. 1894-915 Spytihnev I (? - 915), Duke of Bohemia (894/895 - 915), was the eldest son of Borivoj I. Spytihnev is known solely for his 895 alliance with Arnulf, Duke of Bavaria, (the Diet of Augsburg) separating Bohemia from Great Moravia. Designed to protect Bohemia against the ravages of Magyar raiders, this pact also opened Bohemia to East Frankish Carolingian culture and paved the way for the eventual triumph of Roman Catholicism in Czech spiritual affairs.