Hus, the Hussites and Bohemia Remained in German Hands Even Though Czechs Made up the Majority of the Population

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emotion, Seduction and Intimacy: Alternative Perspectives on Human Behaviour RIDLEY-DUFF, R

Emotion, seduction and intimacy: alternative perspectives on human behaviour RIDLEY-DUFF, R. J. Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/2619/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version RIDLEY-DUFF, R. J. (2010). Emotion, seduction and intimacy: alternative perspectives on human behaviour. Silent Revolution Series . Seattle, Libertary Editions. Repository use policy Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in SHURA to facilitate their private study or for non- commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Silent Revolution Series Emotion Seduction & Intimacy Alternative Perspectives on Human Behaviour Third Edition © Dr Rory Ridley-Duff, 2010 Edited by Dr Poonam Thapa Libertary Editions Seattle © Dr Rory Ridley‐Duff, 2010 Rory Ridley‐Duff has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Acts 1988. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution‐Noncommercial‐No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. Attribution — You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. -

Graeme Small, the Scottish Court in the Fifteenth Century

Graeme Small, The Scottish Court in the Fifteenth Century. A view from Burgundy, in: Werner Paravicini (Hg.): La cour de Bourgogne et l'Europe. Le rayonnement et les limites d’un mode`le culturel; Actes du colloque international tenu à Paris les 9, 10 et 11 octobre 2007, avec le concours de Torsten Hiltmann et Frank Viltart, Ostfildern (Thorbecke) 2013 (Beihefte der Francia, 73), S. 457-474. Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Historischen Institut Paris Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. GRAEME SMALL The Scottish Court in the Fifteenth Century A view from Burgundy Looking at the world of the Scottish court in the fifteenth century, the view from Burgundy was often far from positive. The exile of the Lancastrian royal family in Scotland in 1461, for example, was portrayed in the official ducal chronicle of George Chastelain as a miserable experience. Chastelain records an incident wherein Mar- garet of Anjou was forced to beg, from a tight-fisted Scots archer, for the loan of a groat to make her offering at Mass1. Scottish royal records show that the treatment the queen received was rather more generous, and we may suspect that Chastelain’s colourful account was influenced by literary topoi of long pedigree2. -

Raiders of the Lost Ark

Swiss American Historical Society Review Volume 56 Number 1 Article 12 2020 Full Issue Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review Part of the European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation (2020) "Full Issue," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 56 : No. 1 , Article 12. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol56/iss1/12 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swiss American Historical Society Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. et al.: Full Issue Swiss A1nerican Historical Society REVIEW Volu1ne 56, No. 1 February 2020 Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 2020 1 Swiss American Historical Society Review, Vol. 56 [2020], No. 1, Art. 12 SAHS REVIEW Volume 56, Number 1 February 2020 C O N T E N T S I. Articles Ernest Brog: Bringing Swiss Cheese to Star Valley, Wyoming . 1 Alexandra Carlile, Adam Callister, and Quinn Galbraith The History of a Cemetery: An Italian Swiss Cultural Essay . 13 Plinio Martini and translated by Richard Hacken Raiders of the Lost Ark . 21 Dwight Page Militant Switzerland vs. Switzerland, Island of Peace . 41 Alex Winiger Niklaus Leuenberger: Predating Gandhi in 1653? Concerning the Vindication of the Insurgents in the Swiss Peasant War . 64 Hans Leuenberger Canton Ticino and the Italian Swiss Immigration to California . 94 Tony Quinn A History of the Swiss in California . 115 Richard Hacken II. Reports Fifty-Sixth SAHS Annual Meeting Reports . -

Paoli-Demotivationaltraining.Pdf

Demotivational Training (Éloge de la Démotivation) Guillaume Paoli translated by Vincent Stone First U.S. edition published by Cruel Hospice 2013 Cruel Hospice is a place where a terminally-ill society gets the nasty treatment it deserves. Anyone trying to resuscitate the near dead is a legitimate target for criticism. Printed by LBC Books http://lbcbooks.com Cover art by Tyler Spangler English translation by Vincent Stone Printed in Berkeley First printing, December 2013 To Renate, for so many motives 1 Why Do Something Rather than Nothing? 16 Compulsory Markets 44 The Company Wants What’s Best for You (Don’t Give It to Them) 67 The Work Drug 90 Metamorphoses of the Fetish 122 Canceling the Project Why do something rather than nothing? I Motivated, motivated, We must be motivated. —Neo-Trotskyist refrain To get a donkey to move forward, nothing is better than the proverbial carrot and stick. At least that’s how the story goes. Having known a few muleskinners myself, I never saw a single one resort to this technique. But whatever the reality may be, it’s a useful metaphor that, like many popular expressions, con- tains and condenses phenomena that are more complex than they seem. From the outset, let’s be clear that it is a question of the carrot and the stick, and not one or the other. There’s not an option, but rather a dialectical relation between the two terms. No carrot without the stick, and vice versa. The stick alone, physical punishment without the carrot, is not enough to encourage continuous and resolute forward progress in the animal. -

The German Civil Code

TUE A ERICANI LAW REGISTER FOUNDED 1852. UNIERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA DEPART=ENT OF LAW VOL. {4 0 - S'I DECEMBER, 1902. No. 12. THE GERMAN CIVIL CODE. (Das Biirgerliche Gesetzbuch.) SOURCES-PREPARATION-ADOPTION. The magnitude of an attempt to codify the German civil. laws can be adequately appreciated only by remembering that for more than fifteefn centuries central Europe was the world's arena for startling political changes radically involv- ing territorial boundaries and of necessity affecting private as well as public law. With no thought of presenting new data, but that the reader may properly marshall events for an accurate compre- hension of the irregular development of the law into the modem and concrete results, it is necessary to call attention to some of the political- and social factors which have been potent and conspicuous since the eighth century. Notwithstanding the boast of Charles the Great that he was both master of Europe and the chosen pr6pagandist of Christianity and despite his efforts in urging general accept- ance of the Roman law, which the Latinized Celts of the western and southern parts of his titular domain had orig- THE GERM AN CIVIL CODE. inally been forced to receive and later had willingly retained, upon none of those three points did the facts sustain his van- ity. He was constrained to recognize that beyond the Rhine there were great tribes, anciently nomadic, but for some cen- turies become agricultural when not engaged in their normal and chief occupation, war, who were by no means under his control. His missii or special commissioners to those people were not well received and his laws were not much respected. -

Entrepreneurial Solutions to Online Disinformation: Seeking Scale, Trying for Profit

ENTREPRENEURSHIP & POLICY WORKING PAPER SERIES Entrepreneurial Solutions to Online Disinformation: Seeking Scale, Trying for Profit Anya Schiffrin In 2016, the Nasdaq Educational Foundation awarded the Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) a multi-year grant to support initiatives at the intersection of digital entrepreneurship and public policy. Over the past three years, SIPA has undertaken new research, introduced new pedagogy, launched student venture competitions, and convened policy forums that have engaged scholars across Columbia University as well as entrepreneurs and leaders from both the public and private sectors. New research has covered three broad areas: Cities & Innovation; Digital Innovation & Entrepreneurial Solutions; and Emerging Global Digital Policy. Specific topics have included global education technology; cryptocurrencies and the new technologies of money; the urban innovation environment, with a focus on New York City; government measures to support the digital economy in Brazil, Shenzhen, China, and India; and entrepreneurship focused on addressing misinformation. With special thanks to the Nasdaq Educational Foundation for its support of SIPA’s Entrepreneurship and Policy Initiative. SIPA’s Entrepreneurship & Policy Initiative Working Paper Series Entrepreneurial Solutions to Online Disinformation: Seeking Scale, Trying for Profit By Anya SchiffrinI Executive summary to be tackling the problem of removing dangerous/ille- gal content but are universally resented because they As worries about dis/misinformation online and the profit from the spread of mis/disinformation and have contamination of public discourse continue, and inter- been slow to respond to warnings about the danger- national regulatory standards have yet to be developed, ous effects it is having on society. Facebook has blocked a number of private sector companies have jumped tools promoting transparency of advertising on the into the breach to develop ways to address the problem. -

The Case of Lower Sorbian

Marti Roland Universität des Saarlandes Saarbrücken, Deutschland Codification and Re(tro)codification of a Minority Language: The Case of Lower Sorbian Lower Sorbian – codification – orthography – Slavonic microlanguages The codification of languages or language varieties belongs to the realm of standardology in linguistics (cf. Brozović 1970). It is interesting to note, although not really surprising, that questions of standardology first attracted the interest of linguists in Slavonic-speaking countries, albeit in rather different ways.1 On the one hand it was the Prague school of linguistics that developed a framework for the description of standard languages (cf. Jedlička 1990), prompted at least partly by the diglossic situation of Czech (according to Ferguson 1959). On the other hand it was Soviet linguistics with its hands-on experience of working with the many languages of the Soviet Union that had no written tradition at all or used very imperfect writing systems. The linguistic bases on which theories were developed differed considerably and so did the respective approaches. The Prague school had to deal with reasonably stable stand- ard languages whereas linguists in the Soviet Union often had to create a 1 On standardology with special reference to Slavonic languages, see Müller/ Wingender 2013 and section XXV. in the handbook Die slavischen Sprachen — The Slavic languages (Gutschmidt et al. 2014: 1958–2038), in particular Wingender 2014. - 303 - Marti Roland standard or to replace an existing standard that was unsuitable (or -

The Effect of Mobbing in Workplace on Professional Self-Esteem of Nurses

International Journal of Caring Sciences May-August 2018 Volume 11 | Issue 2| Page 1241 Original Article The Effect of Mobbing in Workplace on Professional Self-Esteem of Nurses Mine Cengiz Ataturk University Nursing Faculty, Psychiatric Nursing Department, Erzurum / Turkey Birsel Canan Demirbag Karadeniz Teknik University Faculty Of Health Sciences, Public Health Nursing Department, Trabzon, Turkey Osman Yiıldizlar Avrasya University Faculty Of Health Sciences, Health Management Department, Trabzon, Turkey Correspondence: Mine Cengiz, Ataturk University Nursing Faculty, Psychiatric Nursing Department, Erzurum, Turkey. [email protected] Abstract This study has been conducted to investigate the effect of mobbing (psychological violence) on professional self- esteem in nurses. This study has been carried out with 188 nurses participating voluntarily in the study at Erzurum Ataturk University Yakutiye Research Hospital between 19 March and 27 July 2016. For the collection of data, an introductory information form, Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R) and Professional Self- Esteem Scale (PSES) have been used. The data were analyzed by the SPSS program with mean, standard deviation, T-test, Mann Whitney U-test. In the results of the study, it has been determined that 55.9% of nurses were under 30 years old, 74.5% were female, 51.1% were married, 40.4% had undergraduate degrees, 70.2% were service nurses, 31.4% did nursing at the institution where they had been for 3-6 years, 79.8% were working 40 hours a week. It has been seen that 40.4% of the nurses are exposed to psychological violence, exposure to negative behavior is moderate ( x̅ = 34.61±12.99) and professional self-esteem is high ( x̅ = 104.92±17.27). -

Archivio Veneto

Anno CXLVI VI serie n. 10 ARCHIVIO DEPUTAZIONE DI STORIA PATRIA VENETO PER LE VENEZIE • ARCHIVIO VENETO VI Serie N. 15 • VENEZIA ISSN 0392-0291 2018 2015 ARCHIVIO VENETO SESTA SERIE - n. 10 (2015) comitato scientifico Piero Del Negro, presidente Dieter Girgensohn - Giuseppe Gullino - Jean-Claude Hocquet Sergej Pavlovic Karpov - Gherardo Ortalli - Maria Francesca Tiepolo Gian Maria Varanini - Wolfgang Wolters Questo numero è stato curato da Giuseppe Gullino comitato di redazione Eurigio Tonetti, coordinatore Michael Knapton - Antonio Lazzarini - Andrea Pelizza - Franco Rossi La rivista efettua il referaggio anonimo e indipendente issn 0392-0291 stampato da cierre grafica - verona 2015 DEPUTAZIONE DI STORIA PATRIA PER LE VENEZIE ARCHIVIO VENETO VENEZIA 2015 DEPUTAZIONE DI STORIA PATRIA PER LE VENEZIE S. Croce, Calle del Tintor 1583 - 30135 VENEZIA Tel. 041 5241009 - Fax 041 5240487 www.veneziastoria.it - e-mail: [email protected] Bianca Strina Lanfranchi1 (27 settembre 1932 - 1° ottobre 2015) In memoriam Bianca Strina nasce a Venezia il 27 settembre 1932. Si laurea in giurispru- denza all’Università degli Studi di Padova l’8 novembre 1955 con una tesi dal titolo La nullità dell’atto costitutivo della società per azioni (relatore: Giorgio Oppo, a. acc. 1954-55). Entra nell’amministrazione archivistica il 1° ottobre 1958, iniziando la sua carriera all’Archivio di Stato di Venezia. In quella prestigiosa sede continua la collaborazione, già iniziata in precedenza, con il Comitato per la pubblicazione delle fonti relative alla storia di Venezia, in particolare con Luigi Lanfranchi con cui realizza non solo alcuni volumi ma anche una operosa sintonia scientifca sfociata qualche anno più tardi in un felice matrimonio. -

Bindex 531..540

Reemers Publishing Services GmbH O:/Wiley/Reihe_Dummies/Andrey/3d/bindex.3d from 27.07.2017 10:15:16 3B2 9.1.580; Page size: 176.00mm x 240.00mm Stichwortverzeichnis A Annan, Kofi 484 Bartholomäusnacht 147 – Appeasement 129 Basel 57, 119, 120, 131, 139, Aarau 221, 227 229 Appenzell 122, 148, 229, 249, 141, 153, 165, 205, 207–210, Aare 298 250, 253, 266, 286, 287, 217, 221, 228, 229, 231, 232, Aargau 107, 249, 253, 274, 300, 320, 350, 364, 423 249, 253–255, 275, 276, 275, 287, 294, 296, 311, 319, – Appenzeller Monatsblatt 300 286, 287, 291, 293, 296, 321 325, 349, 350, 352, Appenzeller Zeitung 300, 318, 319, 321, 324, 325, 331, 353, 367, 377 307, 323 337, 349, 350, 353, 358, Aargauer Volksblatt 465 Aquae Helveticae 49, 51 366–368, 375, 392, 466, Académie Française 296, 297 Arbedo 108 476, 477, 479 Ador, Gustave 410, 422 Arbeiterstimme 385 Basilika 48 Aebli, Hans 136, 137 Arbeitsfrieden 437, 438 Bassanesi, Giovanni 429, 430 Ädilen 52 Arbeitslosenversicherung Batzenkrieg 156 Affäre Bassenesi 429 434, 435 Bauern-, Gewerbe- und Affäre Perregaux de Watte- Arcadius 60 Bürgerpartei 426, 462, 476 ville, die 166 Arianismus 66 Bauernkrieg, Schweizerischer Affäre von Neuenburg, die Arius 66 156 166 ’ Armagnacs 110 Baumgartner, Jakob 314, 320, Affry, Louis d 246, Armbrust 89 328 254–256, 258, 259, – Arnold, Gustav 387 Bay, Ludwig 231 261 265, 268, 272 Arp, Hans 415–417 Beccaria 183, 194 Agaune 65 Arth 340 Begos, Louis 231 Agennum 34 Artillerie 99 Béguelin, Roland 477, 478 Agrarismus 162 Assignaten 216 Belfaux 336 Aix-la-Chapelle 285 Atelier de Mirabeau -

Material Culture and Daily Life in the New City of Prague, 1547-1611

MATERIAL CULTURE AND DAILY LIFE IN THE NEW CITY OF PRAGUE IN THE AGE OF RUDOLF II MEDIUM AEVUM QUOTIDIANUM HERAUSGEGEBEN VON GERHARD JARITZ SONDERBAND VI James R. Palmitessa MATERIAL CULTURE & DAILY LIFE IN THE NEW CITY OF PRAGUE IN THE AGE OF RUDOLF II KREMS 1997 GEDRUCKT MIT UNTERSTÜTZUNG DER KULTURABTEILUNG DES AMTES DER NIEDERÖSTERREICHISCHEN LANDESREGIERUNG Cover illustration: Detail of the New City of Prague from the Sadeler engraving of 1606. The nine-part copper etching measuring 47.6 x 314 cm. is one of the largest of any city in its day. It was a cooperative project of a three-person team belonging to the !arge and sophisticated group of artists at the court of Emperor Rudolf II in Prague. Aegidius Sadeler, the imperial engraver, commissioned the project and printed the copper-etching which was executed by Johannes Wechter after drawings by Philip van den Bosche. In the center of the illustration are the ruins of the Church and Cloister of Mary of the Snow (item no. 84). The broad thoroughfare Na pfikope (•im Graben�), item no. 83, separates the Old City (to the left) from the New City (to the right). To the right of the Church and Cloister of Mary of the Snow is the long Horse Market (today Wenceslaus Square), item no. 88. The New City parish church Sv. Jind.ficha (St. Henry) can be located just above the church and cloister (item no. 87). -ISBN 3-901094 09 1 Herausgeber: Medium Aevum Quotidianum. Gesellschaft zur Erforschung der materiellen Kultur des Mittelalters. Körnermarkt 13, A-3500 Krems, Österreich. -

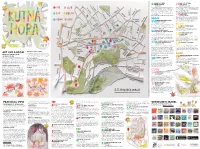

Act Like a Local See Eat Practical Info Drink Relax Shop

HAVE YOU EVER BAR OUT OF TIME 14 BEEN A HIPPIE? 21AND SPACE Jakubská 562 Komenského nám. 39/19 Have you ever gone through a hippie phase in your life? Blues Having a hard time coming up with an idea of how to describe café will definitely take you back there. An endless stock of this place, we assume No Name is really an appropriate name rock’n’roll and bluesy LP’s, your favourite 60s heroes on the for this bar. Anyway, it’s a local favorite for its friendly person- walls and a long haired barkeeper who is a relentless critic of nel, cheap drinks and table football. current politics and society. If you’re lucky you’ll meet local Sun–Thu 18–23, Fri–Sat 18–03 jazz musicians jamming there. If not, at least you can have a quiche, a baguette or a bowl of hot soup while listening to LOCAL CLASSIC WITH STEAM some John Mayall. 22PUNK VIBES Mon 10–19, Tue–Thu 9–19, Fri–Sat 10–22, Sun 11:30–18 Havlíčkovo nám. 552 Whenever we go to the Pod schodama pub, we’ll find some of our friends playing table football or singing along to the DRINK jukebox. Usually open till late night hours, this rusty dive bar is a stronghold for Kutná Hora’s youth, a witness to all the A MEDITATIVE REFUGE FOR important plot twists in our lives. Mon–Sun 18–03 15FANTASY LOVERS Havlíčkovo nám. 84 This shisha scented tea room is a meditative refuge for fanta- RELAX sy lovers.