The Disadvantaged and the Hussite Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Material Culture and Daily Life in the New City of Prague, 1547-1611

MATERIAL CULTURE AND DAILY LIFE IN THE NEW CITY OF PRAGUE IN THE AGE OF RUDOLF II MEDIUM AEVUM QUOTIDIANUM HERAUSGEGEBEN VON GERHARD JARITZ SONDERBAND VI James R. Palmitessa MATERIAL CULTURE & DAILY LIFE IN THE NEW CITY OF PRAGUE IN THE AGE OF RUDOLF II KREMS 1997 GEDRUCKT MIT UNTERSTÜTZUNG DER KULTURABTEILUNG DES AMTES DER NIEDERÖSTERREICHISCHEN LANDESREGIERUNG Cover illustration: Detail of the New City of Prague from the Sadeler engraving of 1606. The nine-part copper etching measuring 47.6 x 314 cm. is one of the largest of any city in its day. It was a cooperative project of a three-person team belonging to the !arge and sophisticated group of artists at the court of Emperor Rudolf II in Prague. Aegidius Sadeler, the imperial engraver, commissioned the project and printed the copper-etching which was executed by Johannes Wechter after drawings by Philip van den Bosche. In the center of the illustration are the ruins of the Church and Cloister of Mary of the Snow (item no. 84). The broad thoroughfare Na pfikope (•im Graben�), item no. 83, separates the Old City (to the left) from the New City (to the right). To the right of the Church and Cloister of Mary of the Snow is the long Horse Market (today Wenceslaus Square), item no. 88. The New City parish church Sv. Jind.ficha (St. Henry) can be located just above the church and cloister (item no. 87). -ISBN 3-901094 09 1 Herausgeber: Medium Aevum Quotidianum. Gesellschaft zur Erforschung der materiellen Kultur des Mittelalters. Körnermarkt 13, A-3500 Krems, Österreich. -

“More Glory Than Blood”: Murder and Martyrdom in the Hussite Crusades

117 “More Glory than Blood”: Murder and Martyrdom in the Hussite Crusades Thomas A. Fudge (Christchurch, New Zealand) In 1418 Pope Martin V urged the ecclesiastical hierarchy in east-central Europe to proceed against the Hussite heretics in all possible manner to bring their dissent to an end.1 Two years later a formal bull of crusade was proclaimed and the cross was preached against the recalcitrant Czechs.2 The story of the crusades which convulsed Bohemia for a dozen years is well known.3 Five times the cross was preached, crusade banners hoisted and tens of thousands of crusaders poured across the Czech frontier with one pre–eminent goal: to eradicate the scourge of heresy. At Prague in 1420, peasant armies commanded by Jan Žižka won an improbable victory and the crusaders, under the personal command of Emperor Sigismund, retreated in disarray and defeat. At Žatec the following year, Hussites once again saw a vastly superior army withdraw disorganized and crushed. In 1422 the crusaders were unable to overcome their internal squabbles long enough to mount any real offensive and once more had little option other than to retreat in dishonour. For five years the crusading cause rested. Then in 1427 the crusaders struck again, first at Stříbro and then at Tachov in western Bohemia. Prokop Holý’s forces scattered them ignominiously. Once more, in 1431, the armies of the church and empire were mustered and with great force marched through the Šumava [Bohemian Forest] to confront the enemies of God. The odds favoured the crusaders. They out–numbered the heretics by a four to one margin, were militarily superior to the flail–touting peasants and were under the command of Friedrich of Brandenburg, veteran warrior in charge of his third crusade, and the spiritual direction of the president of the ecumenical Council of Basel, Cardinal Guiliano Cesarini. -

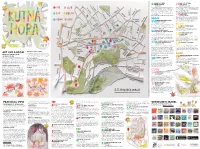

Act Like a Local See Eat Practical Info Drink Relax Shop

HAVE YOU EVER BAR OUT OF TIME 14 BEEN A HIPPIE? 21AND SPACE Jakubská 562 Komenského nám. 39/19 Have you ever gone through a hippie phase in your life? Blues Having a hard time coming up with an idea of how to describe café will definitely take you back there. An endless stock of this place, we assume No Name is really an appropriate name rock’n’roll and bluesy LP’s, your favourite 60s heroes on the for this bar. Anyway, it’s a local favorite for its friendly person- walls and a long haired barkeeper who is a relentless critic of nel, cheap drinks and table football. current politics and society. If you’re lucky you’ll meet local Sun–Thu 18–23, Fri–Sat 18–03 jazz musicians jamming there. If not, at least you can have a quiche, a baguette or a bowl of hot soup while listening to LOCAL CLASSIC WITH STEAM some John Mayall. 22PUNK VIBES Mon 10–19, Tue–Thu 9–19, Fri–Sat 10–22, Sun 11:30–18 Havlíčkovo nám. 552 Whenever we go to the Pod schodama pub, we’ll find some of our friends playing table football or singing along to the DRINK jukebox. Usually open till late night hours, this rusty dive bar is a stronghold for Kutná Hora’s youth, a witness to all the A MEDITATIVE REFUGE FOR important plot twists in our lives. Mon–Sun 18–03 15FANTASY LOVERS Havlíčkovo nám. 84 This shisha scented tea room is a meditative refuge for fanta- RELAX sy lovers. -

Reconstruction Or Reformation the Conciliar Papacy and Jan Hus of Bohemia

Garcia 1 RECONSTRUCTION OR REFORMATION THE CONCILIAR PAPACY AND JAN HUS OF BOHEMIA Franky Garcia HY 490 Dr. Andy Dunar 15 March 2012 Garcia 2 The declining institution of the Church quashed the Hussite Heresy through a radical self-reconstruction led by the conciliar reformers. The Roman Church of the late Middle Ages was in a state of decline after years of dealing with heresy. While the Papacy had grown in power through the Middle Ages, after it fought the crusades it lost its authority over the temporal leaders in Europe. Once there was no papal banner for troops to march behind to faraway lands, European rulers began fighting among themselves. This led to the Great Schism of 1378, in which different rulers in Europe elected different popes. Before the schism ended in 1417, there were three popes holding support from various European monarchs. Thus, when a new reform movement led by Jan Hus of Bohemia arose at the beginning of the fifteenth century, the declining Church was at odds over how to deal with it. The Church had been able to deal ecumenically (or in a religiously unified way) with reforms in the past, but its weakened state after the crusades made ecumenism too great a risk. Instead, the Church took a repressive approach to the situation. Bohemia was a land stained with a history of heresy, and to let Hus's reform go unchecked might allow for a heretical movement on a scale that surpassed even the Cathars of southern France. Therefore the Church, under guidance of Pope John XXIII and Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund of Luxemburg, convened in the Council of Constance in 1414. -

Rhizome Updates from the Institute for the Study of Global Anabaptism

Rhizome Updates from the Institute for the Study of Global Anabaptism VOLUME 7, NUMBER 2 OCTOBER 2020 ISGA Publishes History of the Muria Javanese Mennonite Church in Indonesia Sigit Heru Sukoco Lawrence Yoder An upcoming book published translation by Lawrence M. their own cultural frame of by the ISGA, The Way of the Yoder, with extensive editing reference. Over the course of Gospel in the World of Java: A by ISGA director, John D. its long history, the developing History of the Muria Javanese Roth. communities of Christians Mennonite Church (GITJ), tells joined to form a community The Way of the Gospel in the the story of one branch of known as Gereja Injili di World of Java gives an account the Anabaptist-Mennonite Tanah Jawa (GITJ), or the Mu- of how missionaries of the INSIDE THIS churches in Indonesia. Au- ria Javanese Mennonite Dutch Mennonite Mission, ISSUE: thors Sigit Heru Sukoco and Church. along with indigenous Java- Lawrence M. Yoder originally Research Sym- 1 nese evangelists, sought to One of the indigenous found- posium wrote and published this his- evangelize the people of the ers of the Christian move- Project Updates 2 tory of the Muria Javanese Muria region of north Central ment in the Muria area was a Mennonite Church—known Visiting Scholar 2 Java starting in the 1850s. Javanese mystic, who took the in Indonesia as Gereja Injili di GAMEO 3 While European missionaries name Ibrahim Tunggul Tanah Jawa (GITJ)—in 2010 Editorial 4 functioned out of a western Wulung. This portrait, com- with the title Tata Injil di Bumi cultural framework, the Java- missioned by Lawrence Yoder, Muria. -

The Lower Nobility in the Kingdom of Bohemia in the Early 15Th Century

| 73 The lower nobility in the Kingdom of Bohemia in the early 15 th century, based on the example of Jan Sádlo of Smilkov Silvie Van ēurova Preliminary communication UDK 177.6:32>(437.3)“14“ Abstract During the Hussite revolution, the lower nobility became an important, complex and powerful political force and exerted considerable influence over the Czech Kingdom. The life of Jan Sádlo of Smilkov is used as an example of a lower nobleman who, due to the political situation, was able to become an influential person and become involved in political developments prior to the revolution and in the revolution’s first year. The story of his life offers some possible interpretations of the events that may have impacted the lower nobility’s life at the beginning of 15 th century. Keywords : Lower nobility, Jan Sádlo of Smilkov, pre-Hussite period, Deeds of Complaint, Hussite revolution In the pre-Hussite period, the lower nobility represented a largely heterogeneous and also quite numerous class of medieval society. The influence of this social group on the growing crisis in the pre-Hussite period, its very involvement in the revolution and its in many regards not inconsiderable role during the Hussite Wars have been explored by several generations of historians thus far (Hole ēek 1979, 83-106; Polívka 1982b, Mezník 1987; Pla ēek 2008, Grant 2015). Yet new, unexplored issues still arise regarding the lower nobility’s property (Polívka 1978: 261-272, Jurok 2000: 63-64, Šmahel 2001: 230-242), its local position (Petrá Ÿ 1994: Mezník 1999: 129-137, 362-375; Mlate ēek 2004) and continuity, as well as kinship ties (Mlate ēek 2014) and its involvement in politics. -

Part I the Beginnings

Part I The Beginnings 1 The Problem of Heresy Heresy, and the horror it inspires, intertwines with the history of the Church itself. Jesus warned his disciples against the false prophets who would take His name and the Epistle to Titus states that a heretic, after a first and second abomination, must be rejected. But Paul, writing to the Corinthians, said, `Oportet esse haereses', as the Latin Vulgate translated his phrase ± `there must be heresies, that they which are proved may be manifest among you'1 ± and it was understood by medieval churchmen that they must expect to be afflicted by heresies. Heresy was of great importance in the early centuries in forcing the Church progressively to define its doctrines and to anathematize deviant theological opinions. At times, in the great movements such as Arianism and Gnosticism, heresy seemed to overshadow the Church altogether. Knowledge of the individ- ual heresies and of the definitions which condemned them became a part of the equipment of the learned Christian; the writings of the Fathers wrestled with these deviations, and lists of heresies and handbooks assimilated this experience of the early centuries and handed it on to the Middle Ages. Events after Christianity became the official religion of the Empire also shaped the assumptions with which the Church of the Middle Ages met heresy. After Constantine's conversion, Christians in effect held the power of the State and, despite some hesitations, they used it to impose a uniformity of belief. Both in the eastern and in the western portions of the Empire it became the law that pertinacious heretics were subject to the punishments of exile, branding, confis- cation of goods, or death. -

Crusades 1 Crusades

Crusades 1 Crusades The Crusades were religious conflicts during the High Middle Ages through the end of the Late Middle Ages, conducted under the sanction of the Latin Catholic Church. Pope Urban II proclaimed the first crusade in 1095 with the stated goal of restoring Christian access to the holy places in and near Jerusalem. There followed a further six major Crusades against Muslim territories in the east and Detail of a miniature of Philip II of France arriving in Holy Land numerous minor ones as part of an intermittent 200-year struggle for control of the Holy Land that ended in failure. After the fall of Acre, the last Christian stronghold in the Holy Land, in 1291, Catholic Europe mounted no further coherent response in the east. Many historians and medieval contemporaries, such as Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, give equal precedence to comparable, Papal-blessed military campaigns against pagans, heretics, and people under the ban of excommunication, undertaken for a variety of religious, economic, and political reasons, such as the Albigensian Crusade, the Aragonese Crusade, the Reconquista, and the Northern Crusades. While some historians see the Crusades as part of a purely defensive war against the expansion of Islam in the near east, many see them as part of long-running conflicts at the frontiers of Europe, including the Arab–Byzantine Wars, the Byzantine–Seljuq Wars, and the loss of Anatolia by the Byzantines after their defeat by the Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. Urban II sought to reunite the Christian church under his leadership by providing Emperor Alexios I with military support. -

Not Quite Calvinist: Cyril Lucaris a Reconsideration of His Life and Beliefs

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU School of Theology and Seminary Graduate Papers/Theses School of Theology and Seminary 3-13-2018 Not Quite Calvinist: Cyril Lucaris a Reconsideration of His Life and Beliefs Stephanie Falkowski College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/sot_papers Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Falkowski, Stephanie, "Not Quite Calvinist: Cyril Lucaris a Reconsideration of His Life and Beliefs" (2018). School of Theology and Seminary Graduate Papers/Theses. 1916. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/sot_papers/1916 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Theology and Seminary at DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Theology and Seminary Graduate Papers/Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOT QUITE CALVINIST: CYRIL LUCARIS A RECONSIDERATION OF HIS LIFE AND BELIEFS by Stephanie Falkowski 814 N. 11 Street Virginia, Minnesota A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Seminary of Saint John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Theology. SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY AND SEMINARY Saint John’s University Collegeville, Minnesota March 13, 2018 This thesis was written under the direction of ________________________________________ Dr. Shawn Colberg Director _________________________________________ Dr. Charles Bobertz Second Reader Stephanie Falkowski has successfully demonstrated the use of Greek and Latin in this thesis. -

Pecunia Omnes Vincit

PECUNIA OMNES VINCIT Pecunia Omnes Vincit COIN AS A MEDIUM OF EXCHANGE THROUGHOUT CENTURIES ConfErEnCE ProceedingS OF THE THIRD INTERNATIONAL numiSmatiC ConfErEnCE KraKow, 20-21 may 2016 Edited by Barbara Zając, Paulina Koczwara, Szymon Jellonek Krakow 2018 Editors Barbara Zając Paulina Koczwara Szymon Jellonek Scientific mentoring Dr hab. Jarosław Bodzek Reviewers Prof. Dr hab. Katarzyna Balbuza Dr hab. Jarosław Bodzek Dr Arkadiusz Dymowski Dr Kamil Kopij Dr Piotr Jaworski Dr Dariusz Niemiec Dr Krzysztof Jarzęcki Proofreading Editing Perfection DTP GroupMedia Project of cover design Adrian Gajda, photo a flan mould from archive Paphos Agora Project (www.paphos-agora.archeo.uj.edu.pl/); Bodzek J. New finds of moulds for cast- ing coin flans at the Paphos agora. In. M. Caccamo Caltabiano et al. (eds.), XV Inter- national Numismatic Congress Taormina 2015. Proceedings. Taormina 2017: 463-466. © Copyright by Adrian Gajda and Editors; photo Paphos Agora Project Funding by Financial support of the Foundation of the Students of the Jagiellonian University „BRATNIAK” © Copyright by Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University Krakow 2018 ISBN: 978-83-939189-7-3 Address Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University 11 Gołębia Street 31-007 Krakow Contents Introduction /7 Paulina Koczwara Imitations of Massalian bronzes and circulation of small change in Pompeii /9 Antonino Crisà Reconsidering the Calvatone Hoard 1942: A numismatic case study of the Roman vicus of Bedriacum (Cremona, Italy) /18 Michał Gębczyński Propaganda of the animal depictions on Lydian and Greek coins /32 Szymon Jellonek The foundation scene on Roman colonial coins /60 Barbara Zając Who, why, and when? Pseudo-autonomous coins of Bithynia and Pontus dated to the beginning of the second century AD /75 Justyna Rosowska Real property transactions among citizens of Krakow in the fourteenth century: Some preliminary issues /92 Introduction We would like to present six articles by young researchers from Poland and Great Britain concerning particular aspects of numismatics. -

Crusades 1 Crusades

Crusades 1 Crusades The Crusades were military campaigns sanctioned by the Latin Roman Catholic Church during the High Middle Ages through to the end of the Late Middle Ages. In 1095 Pope Urban II proclaimed the first crusade, with the stated goal of restoring Christian access to the holy places in and near Jerusalem. Many historians and some of those involved at the time, like Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, give equal precedence to other papal-sanctioned military campaigns undertaken for a variety of religious, economic, and political reasons, such as the Albigensian Crusade, the The Byzantine Empire and the Sultanate of Rûm before the First Crusade Aragonese Crusade, the Reconquista, and the Northern Crusades. Following the first crusade there was an intermittent 200-year struggle for control of the Holy Land, with six more major crusades and numerous minor ones. In 1291, the conflict ended in failure with the fall of the last Christian stronghold in the Holy Land at Acre, after which Roman Catholic Europe mounted no further coherent response in the east. Some historians see the Crusades as part of a purely defensive war against the expansion of Islam in the near east, some see them as part of long-running conflict at the frontiers of Europe and others see them as confident aggressive papal led expansion attempts by Western Christendom. The Byzantines, unable to recover territory lost during the initial Muslim conquests under the expansionist Rashidun and Umayyad caliphs in the Arab–Byzantine Wars and the Byzantine–Seljuq Wars which culminated in the loss of fertile farmlands and vast grazing areas of Anatolia in 1071, after a sound victory by the occupying armies of Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert. -

The Teutonic Order Its Secularization

;;?raa!atMjaM». BUU.ETIN OF THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA NEW SERIES No. 128 MAY, 1906 THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA STUDIES IN SOCIOLOGY ECONOMICS POLITICS AND HISTORY VOL. Ill No. 2 THE TEUTONIC ORDER AND ITS SECULARIZATION fi Av3TUDY IN THE PROTESTANT REVOLT BY HARRY GRANT PLUM, M. A. PROFESSOR OF EUROPEAN HISTORY PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY IOWA CITY, IOWA DD 1906. THE UNIVERSITY BUI,I.ETINS PUBUSHED BY THE UNIVERSITY ARE IS SUED EVERY SIX WEEKS DURING THE ACADEMIC YEAR AT 1,EAST SIX NUMBERS EVERY CAI,RNDAR YEAR. ENTERED AT THE POST OFFICE IN IOWA CITY AS SECOND CI,ASS MAII< MATTER. ?r fit BUr,I,ETIN OF THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA NEW SERIES No. 128 MAY, 1906 THE TEUTONIC ORDER AND ITS SECULARIZATION A STUDY IN THE PROTESTANT REVOLT BY HARRY GRANT PLUM, M. A. PROFESSOR OF EUROPEAN HISTORY UERARY TEXAS TECHNOLOGICAL COLLEGE LUBBOCK, TEXAS PUBL,ISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY IOWA CITY, IOWA 1906. THE UNIVERSITY BUl,IvETINS PUBLISHED BY THP: UNIVERSITY ARE IS SUED EVERY SIX WEEKS DURING THE ACADEMIC YEAR AT I,EAST SIX NlMIilvRS EVERY C.A.l,END.\R YEAR. ENTERED AT THE POST OFFICE IN IOWA CITY AS SECOND CLASS MAII, MATTER. PREFACE. This monograph was written to illustrate one of the many phases of the reformation movement. It was at first intended that it should deal only with the materials illustrative of the economic side of the movement for reform. In choosing Prussia for the study, however, this plan was found unsatis factory. There is no adequate or connected account of the early history of the Teutonic Order, of which some knowledge is necessary for an understanding of later developments.