Did Silesia Constitute an Economic Region Between the 13Th and the 15Th Centuries? a Survey of Region-Integrating and Region-Disintegrating Economic Factors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bakalářská Diplomová Práce

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Bakalářská diplomová práce Brno 2013 Sabina Sinkovská Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav germanistiky, nordistiky a nederlandistiky Německý jazyk a literatura Sabina Sinkovská Straßennamen in Troppau Eine Übersicht mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Namensänderungen Bakalářská diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Vlastimil Brom, Ph.D. 2013 Ich erkläre hiermit, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbständig und nur mit Hilfe der angegebenen Literatur geschrieben habe. Brünn, den 18. 5. 2013 …………..………………………………….. An dieser Stelle möchte ich mich bei dem Betreuer meiner Arbeit für seine Bereitwilligkeit und nützlichen Ratschläge herzlich bedanken. Inhalt 1 Einleitung .............................................................................................................................................. 8 2 Onomastik ............................................................................................................................................ 9 2.1 Die Klassifizierung von Eigennamen .............................................................................................. 9 3 Die Toponomastik................................................................................................................................. 9 4 Die Entwicklung der tschechischen Straßennamen ........................................................................... 11 4.1 Veränderungen von Straßennamen ........................................................................................... -

The Case of Upper Silesia After the Plebiscite in 1921

Celebrating the nation: the case of Upper Silesia after the plebiscite in 1921 Andrzej Michalczyk (Max Weber Center for Advanced Cultural and Social Studies, Erfurt, Germany.) The territory discussed in this article was for centuries the object of conflicts and its borders often altered. Control of some parts of Upper Silesia changed several times during the twentieth century. However, the activity of the states concerned was not only confined to the shifting borders. The Polish and German governments both tried to assert the transformation of the nationality of the population and the standardisation of its identity on the basis of ethno-linguistic nationalism. The handling of controversial aspects of Polish history is still a problem which cannot be ignored. Subjects relating to state policy in the western parts of pre-war Poland have been explored, but most projects have been intended to justify and defend Polish national policy. On the other hand, post-war research by German scholars has neglected the conflict between the nationalities in Upper Silesia. It is only recently that new material has been published in England, Germany and Poland. This examined the problem of the acceptance of national orientations in the already existing state rather than the broader topic of the formation and establishment of nationalistic movements aimed (only) at the creation of a nation-state.1 While the new research has generated relevant results, they have however, concentrated only on the broader field of national policy, above all on the nationalisation of the economy, language, education and the policy of changing names. Against this backdrop, this paper points out the effects of the political nationalisation on the form and content of state celebrations in Upper Silesia in the following remarks. -

Józef Dąbrowski (Łódź, July 2008)

Józef Dąbrowski (Łódź, July 2008) Paper Manufacture in Central and Eastern Europe Before the Introduction of Paper-making Machines A múltat tiszteld a jelenben és tartsd a jövőnek. (Respect the past in the present, and keep it to the future) Vörösmarty Mihály (1800-1855) Introduction……1 The genuinely European art of making paper by hand developed in Fabriano and its further modifications… ...2 Some features of writing and printing papers made by hand in Europe……19 Some aspects of paper-history in the discussed region of Europe……26 Making paper by hand in the northern part of Central and Eastern Europe……28 Making paper by hand in the southern part of Central and Eastern Europe……71 Concluding remarks on hand papermaking in Central and Eastern Europe before introducing paper-making machines……107 Acknowledgements……109 Introduction During the 1991 Conference organized at Prato, Italy, many interesting facts on the manufacture and trade of both paper and books in Europe, from the 13th to the 18th centuries, were discussed. Nonetheless, there was a lack of information about making paper by hand in Central and Eastern Europe, as it was highlighted during discussions.1 This paper is aimed at connecting east central and east southern parts of Europe (i.e. without Russia and Nordic countries) to the international stream of development in European hand papermaking before introducing paper-making machines into countries of the discussed region of Europe. This account directed to Anglophones is supplemented with the remarks 1 Simonetta Cavaciocchi (ed.): Produzione e Commercio della Carta e del Libro Secc. XIII-XVIII. -

Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate

Freistaat Sachsen State Chancellery Message and Greeting ................................................................................................................................................. 2 State and People Delightful Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate ......................................................................................... 5 The Saxons – A people unto themselves: Spatial distribution/Population structure/Religion .......................... 7 The Sorbs – Much more than folklore ............................................................................................................ 11 Then and Now Saxony makes history: From early days to the modern era ..................................................................................... 13 Tabular Overview ........................................................................................................................................................ 17 Constitution and Legislature Saxony in fine constitutional shape: Saxony as Free State/Constitution/Coat of arms/Flag/Anthem ....................... 21 Saxony’s strong forces: State assembly/Political parties/Associations/Civic commitment ..................................... 23 Administrations and Politics Saxony’s lean administration: Prime minister, ministries/State administration/ State budget/Local government/E-government/Simplification of the law ............................................................................... 29 Saxony in Europe and in the world: Federalism/Europe/International -

MIESIĘCZNIK MIASTA I GMINY SIEWIERZ Nakład 2000 Egz

MIESIĘCZNIK MIASTA I GMINY SIEWIERZ Nakład 2000 egz. Nr 49 / 05 / 2011 maj 2011 ISSN 1897-9807 BEZPŁATNY SIEWIERZANIE JUŻ PO PODRÓŻY W CZASIE wa sala zebrała przed wielkim ekranem sporą widownię. O 14 maja na siewierskich błoniach odbyła się „Multimedialna podróż w czasie na Zamku Siewier- 20:30, kiedy tylko słońce scho- skim” – innowacyjny happening historyczny, podczas którego uczestnicy mogli przenieść się w wało się za horyzontem, rozpo- przeszłość i doświadczyć odtworzonego świata XV i XVII wieku. częto projekcję fi lmu. Widzowie mogli poznać historię Siewierza, „przenieść się w czasie”, dzięki zastosowanym efektom kompu- terowym oraz poznać opowieść o dzielnych rycerzach, miłości i szlachetności wtopionych w losy komputerowo zrekonstruowane- go zamku. Wieczór uwieńczył pokaz sztucznych ogni, który słychać było nawet w ościennych miej- scowościach. Uczestnicy hap- peningu, zapytani o to, który element imprezy podobał im się najbardziej, wymieniali kapsuły czasu oraz zwiedzanie zamku z przewodnikami. Zwracano uwa- gę na dobry kontakt przewodni- ków ze zwiedzającymi, ciekawy sposób przekazywania wiedzy, Wizualizacja XVII-wiecznego zamku wykorzystana w fi lmie oraz wirtualnym przewodniku piękne stroje oraz atmosferę Uczestnicy mogli podróżować ski wraz z pięcioma doskonale cach. „tamtych czasów” panującą na w specjalnie przygotowanych przygotowanymi przewodnikami Gwiazdą wieczoru była For- zamku. na tę okazję „Kapsułach czasu”. przebranymi w stroje „z epoki”, macja Nieżywych Schabuff, która Happening został zorganizo- Były to stanowiska komputero- wyruszyć w przemarsz wraz z zagrała takie utwory, jak „Lato”, wany w ramach projektu współ- we z zainstalowaną aplikacją, korowodem artystów, zobaczyć „Da da da” czy „ Supermarket”. fi nansowanego przez Unię która pozwalała użytkownikom wybuch armatni (oczywiście Sponsorem koncertu FNS było Europejską ze środków Europej- przespacerować się po wirtual- kontrolowany) oraz nauczyć się Chmielowskie sp. -

The Untapped Potential of Scenic Routes for Geotourism: Case Studies of Lasocki Grzbiet and Pasmo Lesistej (Western and Central Sudeten Mountains, SW Poland)

J. Mt. Sci. (2021) 18(4): 1062-1092 e-mail: [email protected] http://jms.imde.ac.cn https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-020-6630-1 Original Article The untapped potential of scenic routes for geotourism: case studies of Lasocki Grzbiet and Pasmo Lesistej (Western and Central Sudeten Mountains, SW Poland) Dagmara CHYLIŃSKA https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2517-2856; e-mail: [email protected] Krzysztof KOŁODZIEJCZYK* https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3262-311X; e-mail: [email protected] * Corresponding author Department of Regional Geography and Tourism, Institute of Geography and Regional Development, Faculty of Earth Sciences and Environmental Management, University of Wroclaw, No.1, Uniwersytecki Square, 50–137 Wroclaw, Poland Citation: Chylińska D, Kołodziejczyk K (2021) The untapped potential of scenic routes for geotourism: case studies of Lasocki Grzbiet and Pasmo Lesistej (Western and Central Sudeten Mountains, SW Poland). Journal of Mountain Science 18(4). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-020-6630-1 © The Author(s) 2021. Abstract: A view is often more than just a piece of of GIS visibility analyses (conducted in the QGIS landscape, framed by the gaze and evoking emotion. program). Without diminishing these obvious ‘tourism- important’ advantages of a view, it is noteworthy that Keywords: Scenic tourist trails; Scenic drives; View- in itself it might play the role of an interpretative tool, towers; Viewpoints; Geotourism; Sudeten Mountains especially for large-scale phenomena, the knowledge and understanding of which is the goal of geotourism. In this paper, we analyze the importance of scenic 1 Introduction drives and trails for tourism, particularly geotourism, focusing on their ability to create conditions for Landscape, although variously defined (Daniels experiencing the dynamically changing landscapes in 1993; Frydryczak 2013; Hose 2010; Robertson and which lies knowledge of the natural processes shaping the Earth’s surface and the methods and degree of its Richards 2003), is a ‘whole’ and a value in itself resource exploitation. -

Material Culture and Daily Life in the New City of Prague, 1547-1611

MATERIAL CULTURE AND DAILY LIFE IN THE NEW CITY OF PRAGUE IN THE AGE OF RUDOLF II MEDIUM AEVUM QUOTIDIANUM HERAUSGEGEBEN VON GERHARD JARITZ SONDERBAND VI James R. Palmitessa MATERIAL CULTURE & DAILY LIFE IN THE NEW CITY OF PRAGUE IN THE AGE OF RUDOLF II KREMS 1997 GEDRUCKT MIT UNTERSTÜTZUNG DER KULTURABTEILUNG DES AMTES DER NIEDERÖSTERREICHISCHEN LANDESREGIERUNG Cover illustration: Detail of the New City of Prague from the Sadeler engraving of 1606. The nine-part copper etching measuring 47.6 x 314 cm. is one of the largest of any city in its day. It was a cooperative project of a three-person team belonging to the !arge and sophisticated group of artists at the court of Emperor Rudolf II in Prague. Aegidius Sadeler, the imperial engraver, commissioned the project and printed the copper-etching which was executed by Johannes Wechter after drawings by Philip van den Bosche. In the center of the illustration are the ruins of the Church and Cloister of Mary of the Snow (item no. 84). The broad thoroughfare Na pfikope (•im Graben�), item no. 83, separates the Old City (to the left) from the New City (to the right). To the right of the Church and Cloister of Mary of the Snow is the long Horse Market (today Wenceslaus Square), item no. 88. The New City parish church Sv. Jind.ficha (St. Henry) can be located just above the church and cloister (item no. 87). -ISBN 3-901094 09 1 Herausgeber: Medium Aevum Quotidianum. Gesellschaft zur Erforschung der materiellen Kultur des Mittelalters. Körnermarkt 13, A-3500 Krems, Österreich. -

Poles As Pigs in MAUS the Problems with Spiegelman’S MAUS

May 2019 Poles as Pigs in MAUS The Problems with Spiegelman’s MAUS Spiegelman’s representation of Poles as pigs is “a calculated insult” leveled against Poles. The Norton Anthology of American Literature, 7th edition Maus made me feel that Poland was somehow responsible for the Holocaust, or at least that many Poles collaborated in it.1 These materials were prepared for the Canadian Polish Congress by a team of researchers and reviewed for accuracy by historians at the Institute for World Politics, Washington, DC. 1. Background MAUS is a comic book – sometimes called a graphic novel – authored by American cartoonist Art Spiegelman. The core of the book is an extended interview by the author/narrator with his father, a Polish Jew named Vladek, focusing on his experiences as a Holocaust survivor. Although MAUS has been described as both a memoir and fiction, it is widely treated as non-fiction. Time placed it on their list of non-fiction books. MAUS is considered to be a postmodern book. It is a story about storytelling that weaves several conflicting narratives (historical, psychological and autobiographical). The book employs various postmodern techniques as well as older literary devices. A prominent feature of the book is the author’s depiction of 1 Seth J. Frantzman, “Setting History Straight – Poland Resisted Nazis,” Jerusalem Post, January 29, 2018. 1 national groups in the form of different kinds of animals: Jews are drawn as mice, Germans as cats, and (Christian) Poles as pigs. MAUS has been taught widely in U.S. high schools, and even elementary schools, as part of the literature curriculum for many years. -

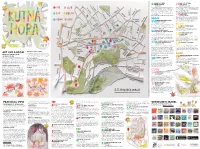

Act Like a Local See Eat Practical Info Drink Relax Shop

HAVE YOU EVER BAR OUT OF TIME 14 BEEN A HIPPIE? 21AND SPACE Jakubská 562 Komenského nám. 39/19 Have you ever gone through a hippie phase in your life? Blues Having a hard time coming up with an idea of how to describe café will definitely take you back there. An endless stock of this place, we assume No Name is really an appropriate name rock’n’roll and bluesy LP’s, your favourite 60s heroes on the for this bar. Anyway, it’s a local favorite for its friendly person- walls and a long haired barkeeper who is a relentless critic of nel, cheap drinks and table football. current politics and society. If you’re lucky you’ll meet local Sun–Thu 18–23, Fri–Sat 18–03 jazz musicians jamming there. If not, at least you can have a quiche, a baguette or a bowl of hot soup while listening to LOCAL CLASSIC WITH STEAM some John Mayall. 22PUNK VIBES Mon 10–19, Tue–Thu 9–19, Fri–Sat 10–22, Sun 11:30–18 Havlíčkovo nám. 552 Whenever we go to the Pod schodama pub, we’ll find some of our friends playing table football or singing along to the DRINK jukebox. Usually open till late night hours, this rusty dive bar is a stronghold for Kutná Hora’s youth, a witness to all the A MEDITATIVE REFUGE FOR important plot twists in our lives. Mon–Sun 18–03 15FANTASY LOVERS Havlíčkovo nám. 84 This shisha scented tea room is a meditative refuge for fanta- RELAX sy lovers. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

Pravěká Minulost Bruntálu a Jeho Horského Okolí1

ČASOPIS SLEZSKÉHO ZEMSKÉHO MUZEA SÉRIE B, 64/2015 Vratislav J a n á k – Petr R a t a j PRAVĚKÁ MINULOST BRUNTÁLU A JEHO HORSKÉHO OKOLÍ1 Abstract In terms of natural conditions the mountain part of the Bruntál district fundamentally differs from the North- Eastern part – Krnov and Osoblaha regions. They are part of the traditional settlement area on the fertile soils of the Upper Silesian loess, with characteristics similar to Central Europe regions - with a few exceptions – i.e. continuity of a relatively dense settlement based on agriculture since the beginning of Neolith in the 6th millen- nium BC until today. The wooded mountain surroundings of Bruntál are regions where continuous settlement started much later, sometimes – as in this case – as late as in the High Middle Ages. If there was an earlier set- tlement, it can be described as sparse and discontinuous in time and space, and with non-agricultural priorities - the main motives of their establishment and episodic existence were apparently communications, exploitation of mineral resources and non-agricultural use of forests. We have no reliable evidence of settlement in the Bruntál region and up to now the archaeologic finds have suggested mere penetration. Most common are iso- lated discoveries of stone industry. Part of them form something like a rim at the very edge of the mountain re- gion and are probably connected with the activities of the lowlands population in the vicinity; the rest suggests penetration into the heart of Jeseníky. Isolated finds from the mountains include coins and metal objects from the Roman era and the beginning of the Migration Period. -

Socio-Economic Study of the Area of Interest

SOCIO-ECONOMIC STUDY OF THE AREA OF INTEREST AIR TRITIA 2018 Elaborated within the project „SINGLE APPROACH TO THE AIR POLLUTION MANAGEMENT SYSTEM FOR THE FUNCTIONAL AREAS OF TRITIS” (hereinafter AIR TRITIA) (č. CE1101), which is co-financed by the European Union through the Interreg CENTRAL EUROPE programme. Socio-economic study of the area of interest has been elaborated by the research institute: ACCENDO – Centrum pro vědu a výzkum, z. ú. Švabinského 1749/19, 702 00 Ostrava – Moravská Ostrava, IČ: 28614950, tel.: +420 596 112 649, web: http://accendo.cz/, e-mail: [email protected] Authors: Ing. Ivana Foldynová, Ph.D. Ing. Petr Proske Mgr. Andrea Hrušková Doc. Ing. Lubor Hruška, Ph.D. RNDr. Ivan Šotkovský, Ph.D. Ing. David Kubáň a další Citation pattern: FOLDYNOVÁ, I.; HRUŠKOVÁ, A.; ŠOTKOVSKÝ, I.; KUBÁŇ, D. a kol. (2018) Socio- ekonomická studie zájmového území“. Ostrava: ACCENDO. Elaborated by: 31. 5. 2018 2 List of Contents List of Abbreviations .................................................................................................. 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 6 1. Specification of the Area of Interest ......................................................................... 7 1.1 ESÚS TRITIA ................................................................................................. 7 1.2 Basic Classification of Territorial Units ................................................................ 8 2. Methodology ....................................................................................................