The Struggle for Upper Silesia, 1919-1922 Author(S): F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Oder-Neisse Line As Poland's Western Border

Piotr Eberhardt Piotr Eberhardt 2015 88 1 77 http://dx.doi.org/10.7163/ GPol.0007 April 2014 September 2014 Geographia Polonica 2015, Volume 88, Issue 1, pp. 77-105 http://dx.doi.org/10.7163/GPol.0007 INSTITUTE OF GEOGRAPHY AND SPATIAL ORGANIZATION POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES www.igipz.pan.pl www.geographiapolonica.pl THE ODER-NEISSE LINE AS POLAND’S WESTERN BORDER: AS POSTULATED AND MADE A REALITY Piotr Eberhardt Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization Polish Academy of Sciences Twarda 51/55, 00-818 Warsaw: Poland e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article presents the historical and political conditioning leading to the establishment of the contemporary Polish-German border along the ‘Oder-Neisse Line’ (formed by the rivers known in Poland as the Odra and Nysa Łużycka). It is recalled how – at the moment a Polish state first came into being in the 10th century – its western border also followed a course more or less coinciding with these same two rivers. In subsequent cen- turies, the political limits of the Polish and German spheres of influence shifted markedly to the east. However, as a result of the drastic reverse suffered by Nazi Germany, the western border of Poland was re-set at the Oder-Neisse Line. Consideration is given to both the causes and consequences of this far-reaching geopolitical decision taken at the Potsdam Conference by the victorious Three Powers of the USSR, UK and USA. Key words Oder-Neisse Line • western border of Poland • Potsdam Conference • international boundaries Introduction districts – one for each successor – brought the loss, at first periodically and then irrevo- At the end of the 10th century, the Western cably, of the whole of Silesia and of Western border of Poland coincided approximately Pomerania. -

WOJCIECH KORFANTY Grzegorz Bębnik Sebastian Rosenbaum Mirosław Węcki

WOJCIECH KORFANTY Grzegorz Bębnik Sebastian Rosenbaum Mirosław Węcki BOHATEROWIE NIEPODLEGŁEJ Wojciech Korfanty. (Zbiory Narodowego Archiwum Cyfrowego) BOHATEROWIE NIEPODLEGŁEJ WOJCIECH KORFANTY 1873–1939 Polityk legenda Wojciech Korfanty jest najbardziej znanym polskim politykiem z Gór- nego Śląska działającym w pierwszej połowie XX w. Był pierwszym politykiem jednoznacznie głoszącym jedność Górnego Śląska z resztą ziem polskich, który został posłem do niemieckiego parlamentu. Kor- fanty odegrał istotną rolę w procesie odbudowy Rzeczypospolitej po 1918 r. W Wielkopolsce należał do Naczelnej Rady Ludowej stanowiącej polityczne centrum tej dzielnicy. Przede wszystkim jednak trzeba go wiązać z aktywnością na rodzimym Górnym Śląsku. Z ramienia rządu polskiego kierował Polskim Komisariatem Plebiscytowym na Górnym Śląsku w latach 1919–1921, koordynując niełatwą walkę o pozyskanie dla Polski głosów Górnoślązaków. W maju 1921 r. stanął na czele III powstania śląskiego jako jego dyktator. Przyczynił się tym walnie do włączenia uprzemysłowionej części regionu górnośląskiego do Rze- czypospolitej. W początkach II Rzeczypospolitej Korfanty był wiodącym polity- kiem w województwie śląskim, a pewną pozycję zdobył także na ogólno- krajowej scenie politycznej. Po zamachu majowym 1926 r. odsunięty od sprawowania władzy, stał się jednym z liderów opozycji antysanacyjnej. Jednocześnie tworzył podwaliny pod polską chadecję i myśl katolicko- 3 -społeczną. Za pośrednictwem wpływowego dziennika „Polonia”, któ- rego był wydawcą, oddziaływał na nastroje opinii publicznej nie tylko w województwie śląskim, lecz także w skali ogólnokrajowej. Ostatnie lata jego życia to dramatyczny okres – musiał udać się na emigrację do Czechosłowacji, a po powrocie do kraju w kwietniu 1939 r. został aresztowany. Zmarł wkrótce po opuszczeniu więzienia. Pochodzenie i edukacja Korfanty pochodził z robotniczej rodziny z Siemianowic Śląskich na Górnym Śląsku. -

The Case of Upper Silesia After the Plebiscite in 1921

Celebrating the nation: the case of Upper Silesia after the plebiscite in 1921 Andrzej Michalczyk (Max Weber Center for Advanced Cultural and Social Studies, Erfurt, Germany.) The territory discussed in this article was for centuries the object of conflicts and its borders often altered. Control of some parts of Upper Silesia changed several times during the twentieth century. However, the activity of the states concerned was not only confined to the shifting borders. The Polish and German governments both tried to assert the transformation of the nationality of the population and the standardisation of its identity on the basis of ethno-linguistic nationalism. The handling of controversial aspects of Polish history is still a problem which cannot be ignored. Subjects relating to state policy in the western parts of pre-war Poland have been explored, but most projects have been intended to justify and defend Polish national policy. On the other hand, post-war research by German scholars has neglected the conflict between the nationalities in Upper Silesia. It is only recently that new material has been published in England, Germany and Poland. This examined the problem of the acceptance of national orientations in the already existing state rather than the broader topic of the formation and establishment of nationalistic movements aimed (only) at the creation of a nation-state.1 While the new research has generated relevant results, they have however, concentrated only on the broader field of national policy, above all on the nationalisation of the economy, language, education and the policy of changing names. Against this backdrop, this paper points out the effects of the political nationalisation on the form and content of state celebrations in Upper Silesia in the following remarks. -

Passive Seismic Experiment 'Animals' in the Polish Sudetes

https://doi.org/10.5194/gi-2021-7 Preprint. Discussion started: 27 April 2021 c Author(s) 2021. CC BY 4.0 License. Passive seismic experiment ‘AniMaLS’ in the Polish Sudetes (NE Variscides) Monika Bociarska1, Julia Rewers1, Dariusz Wójcik1, Weronika Materkowska1, Piotr Środa1 and AniMaLS Working Group* 5 1Department of Seismic Lithospheric Research, Institute of Geophysics Polish Academy of Sciences, Warszawa, 01-452, Poland *A full list of authors and their affiliations appears at the end of the paper. Correspondence to: Monika Bociarska ([email protected]) Abstract. The paper presents information about the seismic experiment AniMaLS which aims to provide a new insight into 10 the crustal and upper mantle structure beneath the Polish Sudetes (NE margin of the Variscan orogen). The seismic array composed of 23 temporary broadband stations was operating continuously for ~2 years (October 2017 and October 2019). The dataset was complemented by records from 8 permanent stations located in the study area and in the vicinity. The stations were deployed with inter-station spacing of approximately 25-30 km. As a result, good quality recordings of local, regional and teleseismic events were obtained. We describe the aims and motivation of the project, the stations deployment 15 procedure, as well as the characteristics of the temporary seismic array and of the permanent stations. Furthermore, this paper includes a description of important issues like: data transmission set-up, status monitoring systems, data quality control, near-surface geological structure beneath stations and related site effects etc. Special attention was paid to verification of correct orientation of the sensors. -

Uneeveningseveralyearsago

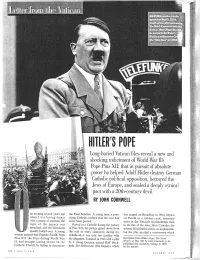

SUdfffiiUeraiKdiesavadio speechfinWay9,3934, »eariya3fearjafierannounce !Uie9leich£oncoRlati^3he Vatican.Aisei^flope^us )isseamed^SLIRetef^ Sa^caonVeconber ahe*»otyireaf'4Dfl9ra: 'i ' TlfraR Long-buried Vatican files reveal a new anc ; shocking indictment of World War IPs Jj; : - I • • H.t.-,. in n. ; Pope Pius XII: that in pursuit of absolute power he helped Adolf Hitler destroy German ^ Catholic political opposition, betrayed the Europe, and sealed a deeply cynica pact with a 20th-century devi!. BBI BY JOHN CORNWELL the Final Solution. A young man, a prac was staged on Broadway in 1964. depict UnewheneveningI wasseveralhavingyearsdinnerago ticing Catholic, insisted that the case had ed Pacelli as a ruthless cynic, interested with a group of students, the never been proved. more in the Vatican's stockholdings than topic of the papacy was Raised as a Catholicduring the papacy in the fate of the Jews. Most Catholics dis broached, and the discussion of Pius XII—his picture gazed down from missed Hochhuth's thesis as implausible, quickly boiled over. A young the wall of every classroom during my but the play sparked a controversy which woman asserted that Eugenio Pacelli, Pope childhood—I was only too familiar with Pius XII, the Pope during World War the allegation. It started in 1963 with a play Excerpted from Hitler's Pope: TheSeci-et II, had brought lasting shame on the by a young German named Rolf Hoch- History ofPius XII. bj' John Comwell. to be published this month byViking; © 1999 Catholic Church by failing to denounce huth. DerStellverti-eter (The Deputy), which by the author. VANITY FAIR OCTOBER 1999 having reliable knowl- i edge of its true extent. -

Breslau Or Wrocław? the Identity of the City in Regards to the World War II in an Autobiographical Reflection

DEBATER A EUROPA Periódico do CIEDA e do CEIS20 , em parceria com GPE e a RCE. N.13 julho/dezembro 2015 – Semestral ISSN 1647-6336 Disponível em: http://www.europe-direct-aveiro.aeva.eu/debatereuropa/ Breslau or Wrocław? The identity of the city in regards to the World War II in an autobiographical reflection Anna Olchówka University of Wrocław E-mail: [email protected] Abstract On the 1st September 1939 a German city Breslau was found 40 kilometers from the border with Poland and the first front lines. Nearly six years later, controlled by the Soviets, the city came under the "Polish administration" in the "Recovered Territories". The new authorities from the beginning virtually denied all the past of the city, began the exchange of population and the gradual erasure of multicultural memory; the heritage of the past recovery continues today. The main objective of this paper is to present the complexity of history through episodes of a city history. The analysis of texts and images, biographies of the inhabitants / immigrants / exiles of Breslau / Wrocław and the results of modern research facilitate the creation of a complex political, economic, social and cultural landscape, rewritten by historical events and resettlement actions. Keywords: Wrocław; Breslau; identity; biography; history Scientific meetings and conferences open academics to new perspectives and face them against different opinions, arguments, works and experiences. The last category, due to its personal and individual aspect, is very special. Experience can be shared and gained at the same time, which is inherent to the continuous development of human beings. Because of its subjectivity, experiences often pose a great methodological problem for the humanistic studies. -

The Historical Cultural Landscape of the Western Sudetes. an Introduction to the Research

Summary The historical cultural landscape of the western Sudetes. An introduction to the research I. Introduction The authors of the book attempted to describe the cultural landscape created over the course of several hundred years in the specific mountain and foothills conditions in the southwest of Lower Silesia in Poland. The pressure of environmental features had an overwhelming effect on the nature of settlements. In conditions of the widespread predominance of the agrarian economy over other categories of production, the foot- hills and mountains were settled later and less intensively than those well-suited for lowland agriculture. This tendency is confirmed by the relatively rare settlement of the Sudetes in the early Middle Ages. The planned colonisation, conducted in Silesia in the 13th century, did not have such an intensive course in mountainous areas as in the lowland zone. The western part of Lower Silesia and the neighbouring areas of Lusatia were colonised by in a planned programme, bringing settlers from the German lan- guage area and using German legal models. The success of this programme is consid- ered one of the significant economic and organisational achievements of Prince Henry I the Bearded. The testimony to the implementation of his plan was the creation of the foundations of mining and the first locations in Silesia of the cities of Złotoryja (probably 1211) and Lwówek (1217), perhaps also Wleń (1214?). The mountain areas further south remained outside the zone of intensive colonisation. This was undertak- en several dozen years later, at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, and mainly in the 14th century, adapting settlement and economy to the special conditions of the natural environment. -

Action Plan Lower Silesia, Poland

Smart and Green Mining Regions of EU Action Plan Lower Silesia, Poland Leading the European policies Research innovation towards more sustainable mining www.interregeurope.eu/remix Action Plan Lower Silesia, Poland Contents Go to the content by clicking the section title 1. General information 3 2. Policy context 4 3. Action 1: Impact on the changes in the Regional 7 Innovation Strategy of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship for 2011–2020 in the area of mining and raw materials 3.1. Relevance to the REMIX project 7 3.2. Nature of the action 9 3.3. Stakeholders involved 12 3.4. Timeframe 14 3.5. Costs 15 3.6. Funding sources 15 4. Action 2: Improving the governance of the RIS3 16 and raising public awareness of the importance of innovative mining in regional economic development 4.1. Relevance to the REMIX project 16 4.2. Nature of the action 18 4.3. Stakeholders involved 19 4.4. Timeframe 20 4.5. Costs 21 4.6. Funding sources 21 Back to Contents 1. General information Project: REMIX – Smart and Green Mining Regions of EU Partner organisation: The Marshal’s Office of Lower Silesian Voivodeship Country: Poland NUTS2 region: PL51 Lower Silesia Contact person: Ewa Król Email address: [email protected] Phone number: +48 71 776 9396 REMIX Interreg Europe . Action plan 3 Back to Contents 2. Policy context The Action Plan aims to impact: Investment for Growth and Jobs programme European Territorial Cooperation programme Other regional development policy instrument Name of the policy instrument addressed: Regional Innovation Strategy of Lower Silesian Voivodeship The Marshal’s Office of Lower Silesian Voivodeship is the regional authority responsible for the management of regional development policy on the territory of Lower Silesia pursuant to Article 3 of the Act of 6 December 2006 (Dziennik Ustaw [Journal of Laws] 2006, No. -

Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate

Freistaat Sachsen State Chancellery Message and Greeting ................................................................................................................................................. 2 State and People Delightful Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate ......................................................................................... 5 The Saxons – A people unto themselves: Spatial distribution/Population structure/Religion .......................... 7 The Sorbs – Much more than folklore ............................................................................................................ 11 Then and Now Saxony makes history: From early days to the modern era ..................................................................................... 13 Tabular Overview ........................................................................................................................................................ 17 Constitution and Legislature Saxony in fine constitutional shape: Saxony as Free State/Constitution/Coat of arms/Flag/Anthem ....................... 21 Saxony’s strong forces: State assembly/Political parties/Associations/Civic commitment ..................................... 23 Administrations and Politics Saxony’s lean administration: Prime minister, ministries/State administration/ State budget/Local government/E-government/Simplification of the law ............................................................................... 29 Saxony in Europe and in the world: Federalism/Europe/International -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Evolving Administrative Approaches Toward Indigenous Silesians

Nationalities Papers (2021), 49: 2, 326–343 doi:10.1017/nps.2020.2 ARTICLE Keeping the “Recovered Territories”: Evolving Administrative Approaches Toward Indigenous Silesians Stefanie M. Woodard* Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, Georgia, USA *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract This article traces changes in Polish administrative approaches toward indigenous Upper Silesians in the 1960s and 1970s. By commissioning reports from voivodeship leaders in 1967, the Ministry of Internal Affairs recognized that native Silesians held reservations toward Poland and, moreover, that postwar “Polonization” efforts may have backfired. These officials further understood the need to act quickly against “disintegration” trends. Although administrators in Katowice and Opole noted that relatively few Silesians engaged in clearly anti-Polish activities, these leaders still believed that West German influence threatened their authority in Silesia. Increasing West German involvement in the area, particularly through care packages and tourism, seemed to support this conclusion. In response to fears of West German infiltration and the rise in emigration applications, local authorities sought to bolster a distinctly Silesian identity. Opole officials in particular argued that strengthening a regional identity, rather than a Polish one, could combat the “tendency toward disintegration” in Silesia. This policy shift underscored an even greater change in attitude toward the borderland population: instead of treating native Silesians -

Cold-Climate Landform Patterns in the Sudetes. Effects of Lithology, Relief and Glacial History

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS CAROLINAE 2000 GEOGRAPHICA, XXXV, SUPPLEMENTUM, PAG. 185–210 Cold-climate landform patterns in the Sudetes. Effects of lithology, relief and glacial history ANDRZEJ TRACZYK, PIOTR MIGOŃ University of Wrocław, Department of Geography, Wrocław, Poland ABSTRACT The Sudetes have the whole range of landforms and deposits, traditionally described as periglacial. These include blockfields and blockslopes, frost-riven cliffs, tors and cryoplanation terraces, solifluction mantles, rock glaciers, talus slopes and patterned ground and loess covers. This paper examines the influence, which lithology and structure, inherited relief and time may have had on their development. It appears that different rock types support different associations of cold climate landforms. Rock glaciers, blockfields and blockstreams develop on massive, well-jointed rocks. Cryogenic terraces, rock steps, patterned ground and heterogenic solifluction mantles are typical for most metamorphic rocks. No distinctive landforms occur on rocks breaking down through microgelivation. The variety of slope form is largely inherited from pre- Pleistocene times and includes convex-concave, stepped, pediment-like, gravitational rectilinear and concave free face-talus slopes. In spite of ubiquitous solifluction and permafrost creep no uniform characteristic ‘periglacial’ slope profile has been created. Mid-Pleistocene trimline has been identified on nunataks in the formerly glaciated part of the Sudetes and in their foreland. Hence it is proposed that rock-cut periglacial relief of the Sudetes is the cumulative effect of many successive cold periods during the Pleistocene and the last glacial period alone was of relatively minor importance. By contrast, slope cover deposits are usually of the Last Glacial age. Key words: cold-climate landforms, the Sudetes 1.