MICROCOSM: Portrait of a European City Major Disturbance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uneeveningseveralyearsago

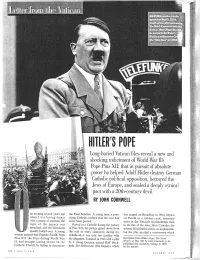

SUdfffiiUeraiKdiesavadio speechfinWay9,3934, »eariya3fearjafierannounce !Uie9leich£oncoRlati^3he Vatican.Aisei^flope^us )isseamed^SLIRetef^ Sa^caonVeconber ahe*»otyireaf'4Dfl9ra: 'i ' TlfraR Long-buried Vatican files reveal a new anc ; shocking indictment of World War IPs Jj; : - I • • H.t.-,. in n. ; Pope Pius XII: that in pursuit of absolute power he helped Adolf Hitler destroy German ^ Catholic political opposition, betrayed the Europe, and sealed a deeply cynica pact with a 20th-century devi!. BBI BY JOHN CORNWELL the Final Solution. A young man, a prac was staged on Broadway in 1964. depict UnewheneveningI wasseveralhavingyearsdinnerago ticing Catholic, insisted that the case had ed Pacelli as a ruthless cynic, interested with a group of students, the never been proved. more in the Vatican's stockholdings than topic of the papacy was Raised as a Catholicduring the papacy in the fate of the Jews. Most Catholics dis broached, and the discussion of Pius XII—his picture gazed down from missed Hochhuth's thesis as implausible, quickly boiled over. A young the wall of every classroom during my but the play sparked a controversy which woman asserted that Eugenio Pacelli, Pope childhood—I was only too familiar with Pius XII, the Pope during World War the allegation. It started in 1963 with a play Excerpted from Hitler's Pope: TheSeci-et II, had brought lasting shame on the by a young German named Rolf Hoch- History ofPius XII. bj' John Comwell. to be published this month byViking; © 1999 Catholic Church by failing to denounce huth. DerStellverti-eter (The Deputy), which by the author. VANITY FAIR OCTOBER 1999 having reliable knowl- i edge of its true extent. -

Albert Breyer's Life and Work Is Closely Connected to the Fate of the Germans of Central Poland and to the Historic Events Between the Two World Wars

Jutta Dennerlein: Breyer the Researcher 1 of 10 Breyer the Researcher Albert Breyer's life and work is closely connected to the fate of the Germans of Central Poland and to the historic events between the two World Wars. This article wants to cover some of the circumstances which had influence on Albert Breyer's life and work. Research for the Heimat As a teacher Albert Breyer belonged to the intellectuals among the German minor- ity in Poland. Already during his stay at St. Petersburg (1913-1918) Breyer got in contact with the publication Geistiges Leben, a monthly periodical for the Germans in Russia. This periodical was initiated by two idealistic teachers from the Dobriner Land and was published in Łódź by Adolf Eichler and Ludwig Wolff. It's subject were the hardships of teachers who had been sent to backward colonies. It supported in a somewhat idealistic way their striving for intellectual challenge, informed about recent teaching methods and also covered the latest developments in questions of the German and Lutheran minorities in Łódź, Poland and Russia. This publication must have had great impact on the young teacher Albert Breyer. He could easily identify himself and his situation in most of the raised questions and issues. Returned to Łódź, Albert Breyer got in touch with Adolf Eichler. Adolf Eichler, who lived in Łódź, was one of the leading characters within the movement of the ethnic Germans in Łódź. He published the daily newspaper Lodzer Rundschau and published during World War I the Deutsche Post and the monthly periodical Geistiges Leben. -

This Is an Electronic Reprint of the Original Article. This Reprint May Differ from the Original in Pagination and Typographic Detail

This is an electronic reprint of the original article. This reprint may differ from the original in pagination and typographic detail. 'Boycott the Nazi Flag' Weiss, Holger Published in: Anti-fascism in the Nordic Countries DOI: 10.4324/9781315171210 Published: 30/01/2019 Document Version (Peer reviewed version when applicable) Document License Publisher rights policy Link to publication Please cite the original version: Weiss, H. (2019). 'Boycott the Nazi Flag': The anti-fascism of the International of Seamen and Harbour Workers. In K. Braskén, N. Copsey, & J. A. Lundin (Eds.), Anti-fascism in the Nordic Countries: New Perspectives, Comparisons and Transnational Connections (pp. 124–142). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315171210 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. This document is downloaded from the Research Information Portal of ÅAU: 29. Sep. 2021 “Boycott the Nazi Flag”: the antifascism of the International of Seamen and Harbour Workers This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge/CRC Press in Anti-Fascism in the Nordic Countries: New Perspectives, Comparisons and Transnational Connections [2019], available online: http://www.routledge.com/[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315171210] Holger Weiss, Åbo Akademi University Introduction This chapter discusses the antifascist campaigns orchestrated by the International of Seamen and Harbour Workers (ISH) in Northern Europe during the first half of the 1930s. -

III. Zentralismus, Partikulare Kräfte Und Regionale Identitäten Im NS-Staat Michael Ruck Zentralismus Und Regionalgewalten Im Herrschaftsgefüge Des NS-Staates

III. Zentralismus, partikulare Kräfte und regionale Identitäten im NS-Staat Michael Ruck Zentralismus und Regionalgewalten im Herrschaftsgefüge des NS-Staates /. „Der nationalsozialistische Staat entwickelte sich zu einem gesetzlichen Zentralismus und zu einem praktischen Partikularismus."1 In dürren Worten brachte Alfred Rosen- berg, der selbsternannte Chefideologe des „Dritten Reiches", die institutionellen Unzu- länglichkeiten totalitärer Machtaspirationen nach dem „Zusammenbruch" auf den Punkt. Doch öffnete keineswegs erst die Meditation des gescheiterten „Reichsministers für die besetzten Ostgebiete"2 in seiner Nürnberger Gefängniszelle den Blick auf die vielfältigen Diskrepanzen zwischen zentralistischem Herrschafts<*«s/>r«c/> und fragmen- tierter Herrschaftspraus im polykratischen „Machtgefüge" des NS-Regimes3. Bis in des- sen höchste Ränge hinein hatte sich diese Erkenntnis je länger desto mehr Bahn gebro- chen. So beklagte der Reichsminister und Chef der Reichskanzlei Hans-Heinrich Lammers, Spitzenrepräsentant der administrativen Funktionseliten im engsten Umfeld des „Füh- rers", zu Beginn der vierziger Jahre die fortschreitende Aufsplitterung der Reichsver- waltung in eine Unzahl alter und neuer Behörden, deren unklare Kompetenzen ein ge- ordnetes, an Rationalitäts- und Effizienzkriterien orientiertes Verwaltungshandeln zuse- hends erschwerten4. Der tiefgreifenden Frustration, welche sich der Ministerialbürokra- tie ob dieser Zustände bemächtigte, hatte Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg schon 1 Alfred Rosenberg, Letzte Aufzeichnungen. Ideale und Idole der nationalsozialistischen Revo- lution, Göttingen 1955, S.260; Hervorhebungen im Original. Vgl. dazu Dieter Rebentisch, Führer- staat und Verwaltung im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Verfassungsentwicklung und Verwaltungspolitik 1939-1945, Stuttgart 1989, S.262; ders., Verfassungswandel und Verwaltungsstaat vor und nach der nationalsozialistischen Machtergreifung, in: Jürgen Heideking u. a. (Hrsg.), Wege in die Zeitge- schichte. Festschrift zum 65. Geburtstag von Gerhard Schulz, Berlin/New York 1989, S. -

The Kpd and the Nsdap: a Sttjdy of the Relationship Between Political Extremes in Weimar Germany, 1923-1933 by Davis William

THE KPD AND THE NSDAP: A STTJDY OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN POLITICAL EXTREMES IN WEIMAR GERMANY, 1923-1933 BY DAVIS WILLIAM DAYCOCK A thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. The London School of Economics and Political Science, University of London 1980 1 ABSTRACT The German Communist Party's response to the rise of the Nazis was conditioned by its complicated political environment which included the influence of Soviet foreign policy requirements, the party's Marxist-Leninist outlook, its organizational structure and the democratic society of Weimar. Relying on the Communist press and theoretical journals, documentary collections drawn from several German archives, as well as interview material, and Nazi, Communist opposition and Social Democratic sources, this study traces the development of the KPD's tactical orientation towards the Nazis for the period 1923-1933. In so doing it complements the existing literature both by its extension of the chronological scope of enquiry and by its attention to the tactical requirements of the relationship as viewed from the perspective of the KPD. It concludes that for the whole of the period, KPD tactics were ambiguous and reflected the tensions between the various competing factors which shaped the party's policies. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE abbreviations 4 INTRODUCTION 7 CHAPTER I THE CONSTRAINTS ON CONFLICT 24 CHAPTER II 1923: THE FORMATIVE YEAR 67 CHAPTER III VARIATIONS ON THE SCHLAGETER THEME: THE CONTINUITIES IN COMMUNIST POLICY 1924-1928 124 CHAPTER IV COMMUNIST TACTICS AND THE NAZI ADVANCE, 1928-1932: THE RESPONSE TO NEW THREATS 166 CHAPTER V COMMUNIST TACTICS, 1928-1932: THE RESPONSE TO NEW OPPORTUNITIES 223 CHAPTER VI FLUCTUATIONS IN COMMUNIST TACTICS DURING 1932: DOUBTS IN THE ELEVENTH HOUR 273 CONCLUSIONS 307 APPENDIX I VOTING ALIGNMENTS IN THE REICHSTAG 1924-1932 333 APPENDIX II INTERVIEWS 335 BIBLIOGRAPHY 341 4 ABBREVIATIONS 1. -

Cr^Ltxj

THE NAZI BLOOD PURGE OF 1934 APPRCWBD": \r H M^jor Professor 7 lOLi Minor Professor •n p-Kairman of the DeparCTieflat. of History / cr^LtxJ~<2^ Dean oiTKe Graduate School IV Burkholder, Vaughn, The Nazi Blood Purge of 1934. Master of Arts, History, August, 1972, 147 pp., appendix, bibliography, 160 titles. This thesis deals with the problem of determining the reasons behind the purge conducted by various high officials in the Nazi regime on June 30-July 2, 1934. Adolf Hitler, Hermann Goring, SS leader Heinrich Himmler, and others used the purge to eliminate a sizable and influential segment of the SA leadership, under the pretext that this group was planning a coup against the Hitler regime. Also eliminated during the purge were sundry political opponents and personal rivals. Therefore, to explain Hitler's actions, one must determine whether or not there was a planned putsch against him at that time. Although party and official government documents relating to the purge were ordered destroyed by Hermann GcTring, certain materials in this category were used. Especially helpful were the Nuremberg trial records; Documents on British Foreign Policy, 1919-1939; Documents on German Foreign Policy, 1918-1945; and Foreign Relations of the United States, Diplomatic Papers, 1934. Also, first-hand accounts, contem- porary reports and essays, and analytical reports of a /1J-14 secondary nature were used in researching this topic. Many memoirs, written by people in a position to observe these events, were used as well as the reports of the American, British, and French ambassadors in the German capital. -

The Struggle for Upper Silesia, 1919-1922 Author(S): F

The Struggle for Upper Silesia, 1919-1922 Author(s): F. Gregory Campbell Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 42, No. 3 (Sep., 1970), pp. 361-385 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1905870 . Accessed: 25/08/2012 14:32 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Modern History. http://www.jstor.org The Strugglefor Upper Silesia, 1919-1922 F. GregoryCampbell University of Chicago At the junction of Central Europe's three old empires lay one of the richestmineral and industrialareas of the continent.A territoryof some 4,000 square miles, Upper Silesia was ruled by Austria and Prussia throughoutmodern history. The northernsections and the area west of the Oder River were exclusivelyagricultural, and inhabitedlargely by Germans.In the extreme southeasterncorner of Upper Silesia, Polish peasants tilled the estates of German magnates. Lying between the Germanand the Polish agriculturalareas was a small triangulararea of mixed populationcontaining a wealth of mines and factories. That Upper Silesian "industrialtriangle" was second only to the Ruhr basin in ImperialGermany; in 1913 Upper Silesian coalfieldsaccounted for 21 percent of German coal production. -

Domniemane I Rzeczywiste Kontakty Prominentów Nazistowskich Z Polskością Przed 1933 Rokiem

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS WRATISLAVIENSIS No 3749 Studia nad Autorytaryzmem i Totalitaryzmem 38, nr 2 Wrocław 2016 DOI: 10.19195/2300-7249.38.2.3 WOJCIECH KAPICA Instytut Historii im. Tadeusza Manteuffla Polskiej Akademii Nauk, Warszawa Domniemane i rzeczywiste kontakty prominentów nazistowskich z polskością przed 1933 rokiem Niezwykle interesująca problematyka stosunku Hitlera i narodowych socja- listów do Polski i Polaków znalazła odbicie w rzetelnych pracach rodzimych ba- daczy (J.W. Borejsza, T. Szarota, E.C. Król, H. Orłowski)1. Chciałbym się skupić w niniejszym skromnym przyczynku na kontaktach, „spotkaniach” prominen- tów nazistowskich (choć jest to „nieostry” termin)2 z szeroko pojętą polskością (Polska, a właściwie ziemie polskie3, Polacy, kultura polska) przed „Machtüber- nahme”, tj. przed 30 stycznia 1933 roku. Niniejsze rozważania absolutnie nie 1 J.W. Borejsza, Antyslawizm Adolfa Hitlera, Warszawa 1988; idem, Śmieszne sto milionów Słowian: wokół światopoglądu Adolfa Hitlera, Warszawa 2006; T. Szarota, Niemcy i Polacy. Wza- jemne postrzeganie i stereotypy, Warszawa 1996; E.C. Król, Polska i Polacy w propagandzie naro- dowego socjalizmu w Niemczech 1919–1945, Warszawa 2006; H. Orłowski, Polnische Wirtshchaft. Nowoczesny niemiecki dyskurs o Polsce, Olsztyn 1998. 2 Za prominentów nazistowskich uznaję w tym przypadku nazistowskich posłów do Reichsta- gu (Mitglieder des Großdeutschen Reichstags) oraz „dębowców” SS i SA, tj. wszystkich wyższych oficerów od SS-Standartenführera i SA-Standartenführera wzwyż. Mam naturalnie świadomość „fasadowego” charakteru Reichstagu w Niemczech (podobnie zresztą było w Związku Sowiec- kim) — mówiono o nim jako o najdrożej na świecie opłacanym „chórze”. Podstawę tej skromnej analizy stanowią biogramy posłów do Reichstagu zamieszczone w specjalnych wydawnictwach poświęconych tej instytucji, zob. Reichstag-Handbuch VI. Wahlperiode 1932, Berlin 1932; Reichs- tag-Handbuch IX. -

1945 – PRELOM S PRETEKLOSTJO Zgodovina Srednjeevropskih Držav Ob Koncu Druge Svetovne Vojne

1945 – A BREAK WITH THE PAST A History of Central European Countries at the End of World War Two 1945 – PRELOM S PRETEKLOSTJO Zgodovina srednjeevropskih držav ob koncu druge svetovne vojne Edited by ZDENKO ČEPIČ Book Editor Zdenko Čepič Editorial board Zdenko Čepič, Slavomir Michalek, Christian Promitzer, Zdenko Radelić, Jerca Vodušek Starič Published by Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino/ Institute for Contemporary History, Ljubljana, Republika Slovenija/Republic of Slovenia Represented by Jerca Vodušek Starič Layout and typesetting Franc Čuden, Medit d.o.o. Printed by Grafika-M s.p. Print run 400 CIP – Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 94(4-191.2)"1945"(082) NINETEEN hundred and forty-five 1945 - a break with the past : a history of central European countries at the end of World War II = 1945 - prelom s preteklostjo: zgodovina srednjeevropskih držav ob koncu druge svetovne vojne / edited by Zdenko Čepič. - Ljubljana : Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino = Institute for Contemporary History, 2008 ISBN 978-961-6386-14-2 1. Vzp. stv. nasl. 2. Čepič, Zdenko 239512832 1945 – A Break with the Past / 1945 – Prelom s preteklostjo CONTENTS Zdenko Čepič, The War is Over. What Now? A Reflection on the End of World War Two ..................................................... 5 Dušan Nećak, From Monopolar to Bipolar World. Key Issues of the Classic Cold War ................................................................. 23 Slavomír Michálek, Czechoslovak Foreign Policy after World War Two. New Winds or Mere Dreams? -

MW5 Layout 10

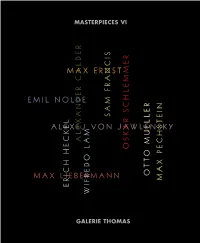

MASTERPIECES VI GALERIE THOMAS MASTERPIECES VI MASTERPIECES VI GALERIE THOMAS CONTENTS ALEXANDER CALDER UNTITLED 1966 6 MAX ERNST LES PEUPLIERS 1939 18 SAM FRANCIS UNTITLED 1964/ 1965 28 ERICH HECKEL BRICK FACTORY 1908 AND HOUSES NEAR ROME 1909 38 PARK OF DILBORN 191 4 50 ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY HEAD OF A WOMAN c. 191 3 58 ABSTRACT HEAD: EARLY LIGHT c. 1920 66 4 WIFREDO LAM UNTITLED 1966 76 MAX LIEBERMANN THE GARDEN IN WANNSEE ... 191 7 86 OTTO MUELLER TW O NUDE GIRLS ... 191 8/20 96 EMIL NOLDE AUTUMN SEA XII ... 191 0106 MAX PECHSTEIN GREAT MILL DITCH BRIDGE 1922 11 6 OSKAR SCHLEMMER TWO HEADS AND TWO NUDES, SILVER FRIEZE IV 1931 126 5 UNTITLED 1966 ALEXANDER CALDER sheet metal and wire, painted Provenance 1966 Galerie Maeght, Paris 38 .1 x 111 .7 x 111 .7 cm Galerie Marconi, Milan ( 1979) 15 x 44 x 44 in. Private Collection (acquired from the above in 1979) signed with monogram Private collection, USA (since 2 01 3) and dated on the largest red element The work is registered in the archives of the Calder Foundation, New York under application number A25784. 8 UNTITLED 1966 ALEXANDER CALDER ”To most people who look at a mobile, it’s no more time, not yet become an exponent of kinetic art than a series of flat objects that move. To a few, in the original sense of the word, but an exponent though, it may be poetry.” of a type of performance art that more or less Alexander Calder invited the participation of the audience. -

Und Gauleiter Der NSDAP

MARTIN MOLL STEUERUNGSINSTRUMENT IM „ÄMTERCHAOS"? Die Tagungen der Reichs- und Gauleiter der NSDAP I. Nahezu sämtliche Analysen des nationalsozialistischen Herrschaftssystems stimmen darin überein, dass der Staat Hitlers je länger desto mehr durch eine fortschreitende Auflösung ordnungsstaatlicher Strukturen geprägt gewesen sei, durch polykratische Kompetenzkämpfe sowie die Verselbständigung sektoraler und regionaler („Gaufürs ten") Partikularherrschaften, über denen Hitler als vermeintlich omnipotenter Füh rer seine Koordinierungsrolle immer weniger ausgeübt habe1. Spätestens seit 1938 habe mit dem völligen Wegfall der schon zuvor immer sporadischer anberaumten Ka binettssitzungen jegliche geordnete Regierungstätigkeit ihr Ende gefunden; es habe sich hierbei um einen Prozess gehandelt, der nach Kriegsbeginn als Folge von Hitlers Rückzug in seine entlegenen Hauptquartiere und seiner vorrangigen Befassung mit militärischen Angelegenheiten noch eine erhebliche Beschleunigung erfahren habe. Der Zugang zum Diktator sei von grauen Eminenzen, insbesondere von Martin Bor mann, zunehmend monopolisiert und abgeschnürt worden, so dass nur mehr eine Handvoll seiner Paladine aus dem engsten Führungszirkel ungehinderten und vor al lem regelmäßigen Zutritt zum Führerhauptquartier gehabt haben2. Hitlers Kontakte mit den Vertretern des staatlichen Verwaltungsapparates wie auch der Partei seien zu nehmend marginalisiert worden, ja der Diktator habe darüber hinaus jede institutio nalisierte Kommunikation zwischen den nachgeordneten Herrschaftsträgern -

Galicia: a Multi-Ethnic Overview and Settlement History with Special Reference to Bukovina by Irmgard Hein Ellingson1 Tam I Kiedys - There Once Upon a Time

Galicia: A Multi-Ethnic Overview and Settlement History with Special Reference to Bukovina by Irmgard Hein Ellingson1 tam i kiedys - there once upon a time Family history researchers place great value upon name of the village from which he emigrated or the place in primary source documents. We want to seek out the original which he settled, we assume that no one does - and that we church records, ship lists, census lists, land records and other will be the ones to discover the family’s “origin.” forms of documentation that may establish someone’s If you had German ancestors in Galicia or Bukovina, presence at a certain location and at a particular point in time. whether they were Evangelical or Catholic, from Most will begin by visiting a local Family History Center to southwestern Germany or from Bohemia, much of this determine record availability and as soon as possible, want information may already be a matter of record and has been to read films to find ancestors and their family groups. for decades. Researchers such as Dr. Franz Wilhelm and Dr. Very few, however, take any time to read and learn Josef Kallbrunner as well as Ludwig Schneider reviewed about the people, places, and the times in which their lists of late eighteenth-century immigrants who registered at ancestors lived. Instead they tend to dive into the records various points on the route to settlement in the eastern with a Star Trek mentality: Genealogy, the final frontier. Habsburg empire. Wilhelm and Kallbrunner’s Quellen zur These are the voyages of the family history researcher.