Vol. 18 2013 Vol. 18 2013 KINGS IN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crusading, the Military Orders, and Sacred Landscapes in the Baltic, 13Th – 14Th Centuries ______

TERRA MATRIS: CRUSADING, THE MILITARY ORDERS, AND SACRED LANDSCAPES IN THE BALTIC, 13TH – 14TH CENTURIES ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the School of History, Archaeology and Religion Cardiff University ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in History & Welsh History (2018) ____________________________________ by Gregory Leighton Abstract Crusading and the military orders have, at their roots, a strong focus on place, namely the Holy Land and the shrines associated with the life of Christ on Earth. Both concepts spread to other frontiers in Europe (notably Spain and the Baltic) in a very quick fashion. Therefore, this thesis investigates the ways that this focus on place and landscape changed over time, when crusading and the military orders emerged in the Baltic region, a land with no Christian holy places. Taking this fact as a point of departure, the following thesis focuses on the crusades to the Baltic Sea Region during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. It considers the role of the military orders in the region (primarily the Order of the Teutonic Knights), and how their participation in the conversion-led crusading missions there helped to shape a distinct perception of the Baltic region as a new sacred (i.e. Christian) landscape. Structured around four chapters, the thesis discusses the emergence of a new sacred landscape thematically. Following an overview of the military orders and the role of sacred landscpaes in their ideology, and an overview of the historiographical debates on the Baltic crusades, it addresses the paganism of the landscape in the written sources predating the crusades, in addition to the narrative, legal, and visual evidence of the crusade period (Chapter 1). -

The Crusade of Andrew II, King of Hungary, 1217-1218

IACOBVS REVIST A DE ESTUDIOS JACOBEOS Y MEDIEVALES C@/llOj. ~1)OI I 1 ' I'0 ' cerrcrzo I~n esrrrotos r~i corrnrro n I santiago I ' s a t'1 Cl fJ r1 n 13-14 SAHACiVN (LEON) - 2002 CENTRO DE ESTVDIOS DEL CAMINO DE SANTIACiO The Crusade of Andrew II, King of Hungary, 1217-1218 Laszlo VESZPREMY Instituto Historico Militar de Hungria Resumen: Las relaciones entre los cruzados y el Reino de Hungria en el siglo XIII son tratadas en la presente investigacion desde la perspectiva de los hungaros, Igualmente se analiza la politica del rey cruzado magiar Andres Il en et contexto de los Balcanes y del Imperio de Oriente. Este parece haber pretendido al propio trono bizantino, debido a su matrimonio con la hija del Emperador latino de Constantinopla. Ello fue uno de los moviles de la Quinta Cruzada que dirigio rey Andres con el beneplacito del Papado. El trabajo ofre- ce una vision de conjunto de esta Cruzada y del itinerario del rey Andres, quien volvio desengafiado a su Reino. Summary: The main subject matter of this research is an appro- ach to Hungary, during the reign of Andrew Il, and its participation in the Fifth Crusade. To achieve such a goal a well supported study of king Andrew's ambitions in the Balkan region as in the Bizantine Empire is depicted. His marriage with a daughter of the Latin Emperor of Constantinople seems to indicate the origin of his pre- tensions. It also explains the support of the Roman Catholic Church to this Crusade, as well as it offers a detailed description of king Andrew's itinerary in Holy Land. -

Summer 2014 (02) Gdańsk Sopot Gdynia

GDAŃSK SOPOT GDYNIA SUMMER 2014 (02) If Poland is your call then you Om du ringer till Polen, då should dial +48 before. måste du ringa med +48. If Poland is your destination, Om du besöker Polen, då then you have to visit Gdańsk. måste du besöka Gdańsk. Whether you come here on board of one of the Oavsett om du reser med Stena Line eller flyger med Stena Line’s cruises or WizzAir planes, you will Wizzair, så kan du behöva en praktisk följeslagare när make use of this handy companion. It will show you du är på resande fot. Tiningen du nu har i handen skall a little of everything here, no matter if you are just inte ses som någon reseguide, men skall ge dig tips och passing by, seek a safe haven inside Kashubian for kanske plantera ett frö om vad som går att upplevas i est or want to enjoy vibrant Polish Riviera. And you regionen. Vi vill visa dig att här är allt nära och lätt att can’t miss its beating heart known in Poland as Tric nå. Välkommen till Polen! ity – Gdańsk, Sopot and Gdynia. Three cities, three distinct stories, combined in one unique narrative. Pomorskie | En stor upplevelse The magazine you are reading is not a guide of any kind and has no ambition to show you all you can experi ence in the region. What it can do however, is give you a hint and maybe plant a seed of inter est. Whatever you will read here and would like to explore – is at hand’s reach. -

The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade

Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 18 January 2017 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PRUSSIAN CRUSADE The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade explores the archaeology and material culture of the Crusade against the Prussian tribes in the thirteenth century, and the subsequent society created by the Teutonic Order that lasted into the six- teenth century. It provides the first synthesis of the material culture of a unique crusading society created in the south-eastern Baltic region over the course of the thirteenth century. It encompasses the full range of archaeological data, from standing buildings through to artefacts and ecofacts, integrated with writ- ten and artistic sources. The work is sub-divided into broadly chronological themes, beginning with a historical outline, exploring the settlements, castles, towns and landscapes of the Teutonic Order’s theocratic state and concluding with the role of the reconstructed and ruined monuments of medieval Prussia in the modern world in the context of modern Polish culture. This is the first work on the archaeology of medieval Prussia in any lan- guage, and is intended as a comprehensive introduction to a period and area of growing interest. This book represents an important contribution to promot- ing international awareness of the cultural heritage of the Baltic region, which has been rapidly increasing over the last few decades. Aleksander Pluskowski is a lecturer in Medieval Archaeology at the University of Reading. Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 -

Material Culture and Daily Life in the New City of Prague, 1547-1611

MATERIAL CULTURE AND DAILY LIFE IN THE NEW CITY OF PRAGUE IN THE AGE OF RUDOLF II MEDIUM AEVUM QUOTIDIANUM HERAUSGEGEBEN VON GERHARD JARITZ SONDERBAND VI James R. Palmitessa MATERIAL CULTURE & DAILY LIFE IN THE NEW CITY OF PRAGUE IN THE AGE OF RUDOLF II KREMS 1997 GEDRUCKT MIT UNTERSTÜTZUNG DER KULTURABTEILUNG DES AMTES DER NIEDERÖSTERREICHISCHEN LANDESREGIERUNG Cover illustration: Detail of the New City of Prague from the Sadeler engraving of 1606. The nine-part copper etching measuring 47.6 x 314 cm. is one of the largest of any city in its day. It was a cooperative project of a three-person team belonging to the !arge and sophisticated group of artists at the court of Emperor Rudolf II in Prague. Aegidius Sadeler, the imperial engraver, commissioned the project and printed the copper-etching which was executed by Johannes Wechter after drawings by Philip van den Bosche. In the center of the illustration are the ruins of the Church and Cloister of Mary of the Snow (item no. 84). The broad thoroughfare Na pfikope (•im Graben�), item no. 83, separates the Old City (to the left) from the New City (to the right). To the right of the Church and Cloister of Mary of the Snow is the long Horse Market (today Wenceslaus Square), item no. 88. The New City parish church Sv. Jind.ficha (St. Henry) can be located just above the church and cloister (item no. 87). -ISBN 3-901094 09 1 Herausgeber: Medium Aevum Quotidianum. Gesellschaft zur Erforschung der materiellen Kultur des Mittelalters. Körnermarkt 13, A-3500 Krems, Österreich. -

Firearms and Artillery in Jan Długosz's Annales Seu Cronicae Incliti Regni Poloniae

FASCICULI ARCHAEOLOGIAE HISTORICAE FASC. XXV, PL ISSN 0860-0007 JAN SZYMCZAK FIREARMS AND ARTILLERY IN JAN DŁUGOSZ’S ANNALES SEU CRONICAE INCLITI REGNI POLONIAE Jan Długosz (Johannes Dlugossius), whose 600th birth- and a metal arrow being thrown from its barrel. Another day anniversary will be celebrated in 2015, is counted handwritten copy by Walter de Milimete, entitled De secre- among the greatest chroniclers of fifteenth-century Europe. tis secretorum, containing a figure representing a similarly As the present volume of „Fasciculi Archaeologiae His- shaped cannon surrounded by four gunners, is held at the toricate” is devoted to the issue of firearms and artillery, British Museum in London. I would like to come back to the remarks on this question As far as battlefield activities are concerned, the year made by undoubtedly the most outstanding Polish annalist 1331, when cannons were used during the siege of Civi- in his largest work entitled „Annales seu Cronicae incliti dale del Friuli in northern Italy, deserves special attention. Regni Poloniae”1. The use of cannons was also mentioned during sieges in *** France and England throughout 1338, as well as in Spain It is a well known fact that in the case of firearms and in 1342. Cannons were recorded in the municipal accounts heavy guns, projectiles are launched due to a propelling of Aachen, Germany, in 1346. In the same year, pieces force generated by the combustion of gunpowder (originally of artillery were first used in open battle at Crécy. Those only black powder was used for this purpose). This propel- were the beginnings of artillery in Europe. -

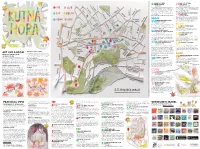

Act Like a Local See Eat Practical Info Drink Relax Shop

HAVE YOU EVER BAR OUT OF TIME 14 BEEN A HIPPIE? 21AND SPACE Jakubská 562 Komenského nám. 39/19 Have you ever gone through a hippie phase in your life? Blues Having a hard time coming up with an idea of how to describe café will definitely take you back there. An endless stock of this place, we assume No Name is really an appropriate name rock’n’roll and bluesy LP’s, your favourite 60s heroes on the for this bar. Anyway, it’s a local favorite for its friendly person- walls and a long haired barkeeper who is a relentless critic of nel, cheap drinks and table football. current politics and society. If you’re lucky you’ll meet local Sun–Thu 18–23, Fri–Sat 18–03 jazz musicians jamming there. If not, at least you can have a quiche, a baguette or a bowl of hot soup while listening to LOCAL CLASSIC WITH STEAM some John Mayall. 22PUNK VIBES Mon 10–19, Tue–Thu 9–19, Fri–Sat 10–22, Sun 11:30–18 Havlíčkovo nám. 552 Whenever we go to the Pod schodama pub, we’ll find some of our friends playing table football or singing along to the DRINK jukebox. Usually open till late night hours, this rusty dive bar is a stronghold for Kutná Hora’s youth, a witness to all the A MEDITATIVE REFUGE FOR important plot twists in our lives. Mon–Sun 18–03 15FANTASY LOVERS Havlíčkovo nám. 84 This shisha scented tea room is a meditative refuge for fanta- RELAX sy lovers. -

Department of Human Geography & Planning, Faculty of Geosciences

Department of Human Geography & Planning, Faculty of Geosciences KLEMENTYNA GĄSIENICA – BYRCYN Student number: 3202739 THE INFLUENCE OF THE PROPERTY RESTITUTION IN THE TATRA MOUNTAINS ON THEIR CURRENT AND FUTURE NATURE PROTECTION MANAGEMENT Master thesis Human Geography and Spatial Planning Written under the supervision of Dr Hans Renes UTRECHT 2010 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This Master thesis would not have been possible without the guidance and help of several individuals who in one way or another contributed and extended their valuable assistance in the preparation and completion of this study. First and foremost, my utmost gratitude to my supervisor, Dr Hans Renes, whose direction, assistance, and guidance enabled me to accomplish thesis research work. Furthermore, I would like to thank Dr Barbara Chovancová and Dr Milan Koreň from the State Forest of TANAP, Slovakia who despite the distance have scrupulously provided me with the information I needed. I am also indebted to my parents, Bożena and Wojciech Gąsienica-Byrcyn, without whose moral support, and steadfast encouragement to complete this study this thesis would not be made possible. Last but not the least, I offer my regards to all interviewees who supported me in any respect during the completion of the project. 2 TABLE OF CONTENT 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 4 2. Terminology ........................................................................................................................ -

Memoirs of Hydrography

MEMOIRS 07 HYDROGRAPHY INCLUDING Brief Biographies of the Principal Officers who have Served in H.M. NAVAL SURVEYING SERVICE BETWEEN THE YEARS 1750 and 1885 COMPILED BY COMMANDER L. S. DAWSON, R.N. I 1s t tw o PARTS. P a r t II.—1830 t o 1885. EASTBOURNE: HENRY W. KEAY, THE “ IMPERIAL LIBRARY.” iI i / PREF A CE. N the compilation of Part II. of the Memoirs of Hydrography, the endeavour has been to give the services of the many excellent surveying I officers of the late Indian Navy, equal prominence with those of the Royal Navy. Except in the geographical abridgment, under the heading of “ Progress of Martne Surveys” attached to the Memoirs of the various Hydrographers, the personal services of officers still on the Active List, and employed in the surveying service of the Royal Navy, have not been alluded to ; thereby the lines of official etiquette will not have been over-stepped. L. S. D. January , 1885. CONTENTS OF PART II ♦ CHAPTER I. Beaufort, Progress 1829 to 1854, Fitzroy, Belcher, Graves, Raper, Blackwood, Barrai, Arlett, Frazer, Owen Stanley, J. L. Stokes, Sulivan, Berard, Collinson, Lloyd, Otter, Kellett, La Place, Schubert, Haines,' Nolloth, Brock, Spratt, C. G. Robinson, Sheringham, Williams, Becher, Bate, Church, Powell, E. J. Bedford, Elwon, Ethersey, Carless, G. A. Bedford, James Wood, Wolfe, Balleny, Wilkes, W. Allen, Maury, Miles, Mooney, R. B. Beechey, P. Shortland, Yule, Lord, Burdwood, Dayman, Drury, Barrow, Christopher, John Wood, Harding, Kortright, Johnson, Du Petit Thouars, Lawrance, Klint, W. Smyth, Dunsterville, Cox, F. W. L. Thomas, Biddlecombe, Gordon, Bird Allen, Curtis, Edye, F. -

Literature of the Low Countries

Literature of the Low Countries A Short History of Dutch Literature in the Netherlands and Belgium Reinder P. Meijer bron Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries. A short history of Dutch literature in the Netherlands and Belgium. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague / Boston 1978 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/meij019lite01_01/colofon.htm © 2006 dbnl / erven Reinder P. Meijer ii For Edith Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries vii Preface In any definition of terms, Dutch literature must be taken to mean all literature written in Dutch, thus excluding literature in Frisian, even though Friesland is part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, in the same way as literature in Welsh would be excluded from a history of English literature. Similarly, literature in Afrikaans (South African Dutch) falls outside the scope of this book, as Afrikaans from the moment of its birth out of seventeenth-century Dutch grew up independently and must be regarded as a language in its own right. Dutch literature, then, is the literature written in Dutch as spoken in the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the so-called Flemish part of the Kingdom of Belgium, that is the area north of the linguistic frontier which runs east-west through Belgium passing slightly south of Brussels. For the modern period this definition is clear anough, but for former times it needs some explanation. What do we mean, for example, when we use the term ‘Dutch’ for the medieval period? In the Middle Ages there was no standard Dutch language, and when the term ‘Dutch’ is used in a medieval context it is a kind of collective word indicating a number of different but closely related Frankish dialects. -

The Clash Between Pagans and Christians: the Baltic Crusades from 1147-1309

The Clash between Pagans and Christians: The Baltic Crusades from 1147-1309 Honors Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in History in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Donald R. Shumaker The Ohio State University May 2014 Project Advisor: Professor Heather J. Tanner, Department of History 1 The Baltic Crusades started during the Second Crusade (1147-1149), but continued into the fifteenth century. Unlike the crusades in the Holy Lands, the Baltic Crusades were implemented in order to combat the pagan tribes in the Baltic. These crusades were generally conducted by German and Danish nobles (with occasional assistance from Sweden) instead of contingents from England and France. Although the Baltic Crusades occurred in many different countries and over several centuries, they occurred as a result of common root causes. For the purpose of this study, I will be focusing on the northern crusades between 1147 and 1309. In 1309 the Teutonic Order, the monastic order that led these crusades, moved their headquarters from Venice, where the Order focused on reclaiming the Holy Lands, to Marienberg, which was on the frontier of the Baltic Crusades. This signified a change in the importance of the Baltic Crusades and the motivations of the crusaders. The Baltic Crusades became the main theater of the Teutonic Order and local crusaders, and many of the causes for going on a crusade changed at this time due to this new focus. Prior to the year 1310 the Baltic Crusades occurred for several reasons. A changing knightly ethos combined with heightened religious zeal and the evolution of institutional and ideological changes in just warfare and forced conversions were crucial in the development of the Baltic Crusades. -

An Offer for Tourists

Lidzbark Warmiński Bytów Olsztyn Lębork Kętrzyn Malbork Ryn Ostróda Człuchów Dzierzgoń Gniew Kwidzyn Nidzica Nowe Sztum Działdowo othic castles - an offer for tourists GCzłuchów • Bytów • Lębork • Gniew • Nowe Kwidzyn • Sztum • Malbork • Dzierzgoń Ostróda • Nidzica • Działdowo • Olsztyn Lidzbark Warmiński • Kętrzyn • Ryn 1 Stowarzyszenie gmin „Polskie zamki gotyckie” Stowarzyszenie gmin 10-006 Olsztyn, ul. Pieniężnego 10, tel./fax +48 89 535 32 76 e-mail: [email protected] „Polskie zamki gotyckie” http://www.zamkigotyckie.org.pl othic castles - an offer for tourists GCzłuchów • Bytów • Lębork • Gniew • Nowe Kwidzyn • Sztum • Malbork • Dzierzgoń Ostróda • Nidzica • Działdowo • Olsztyn Lidzbark Warmiński • Kętrzyn • Ryn The task was co-financed from the funds of the local governments of the Province of Pomerania and the Province of Warmia and Mazury. ISBN 978-83-66075-21-4 Pracownia Wydawnicza ElSet, Olsztyn tel. 89 534 99 25, e-mail: [email protected] 2 3 CULTURE TOURISM AND ACCOMODATION IN HISTORIC BUILDINGS ric entourage. Under a huge canopy and stylish chandeliers, there are long tables with plentiful food and drinks that can sit up to 350 guests. The invitees wear medieval costume: knight tunics for men, gowns for ladies and children. The cooks celebrate the event by bringing delicacies and home-made dishes special- ly created for the occasion. The waiters fill chalices for the guests to raise toast. Our Chivalric or Teutonic Feast on the castle courtyard will take you back to the colourful times of the Middle ages. The Teutonic commander with knights in armour will lead the festivities. Volunteers can try on a knight’s armour, or learn medieval dances.