Understanding Organised Crime: a Legal Comparison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

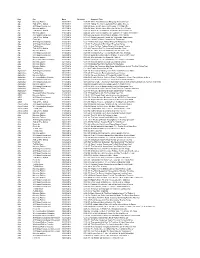

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0:04:09 When Should Seniors Hang Up The Car Keys? Age Talk Of The Nation 10/15/2012 0:30:20 Taking The Car Keys Away From Older Drivers Age All Things Considered 10/16/2012 0:05:29 Home Health Aides: In Demand, Yet Paid Little Age Morning Edition 10/17/2012 0:04:04 Home Health Aides Often As Old As Their Clients Age Talk Of The Nation 10/25/2012 0:30:21 'Elders' Seek Solutions To World's Worst Problems Age Morning Edition 11/01/2012 0:04:44 Older Voters Could Decide Outcome In Volatile Wisconsin Age All Things Considered 11/01/2012 0:03:24 Low-Income New Yorkers Struggle After Sandy Age Talk Of The Nation 11/01/2012 0:16:43 Sandy Especially Tough On Vulnerable Populations Age Fresh Air 11/05/2012 0:06:34 Caring For Mom, Dreaming Of 'Elsewhere' Age All Things Considered 11/06/2012 0:02:48 New York City's Elderly Worry As Temperatures Dip Age All Things Considered 11/09/2012 0:03:00 The Benefit Of Birthdays? Freebies Galore Age Tell Me More 11/12/2012 0:14:28 How To Start Talking Details With Aging Parents Age Talk Of The Nation 11/28/2012 0:30:18 Preparing For The Looming Dementia Crisis Age Morning Edition 11/29/2012 0:04:15 The Hidden Costs Of Raising The Medicare Age Age All Things Considered 11/30/2012 0:03:59 Immigrants Key To Looming Health Aide Shortage Age All Things Considered 12/04/2012 0:03:52 Social Security's COLA: At Stake In 'Fiscal Cliff' Talks? Age Morning Edition 12/06/2012 0:03:49 Why It's Easier To Scam The Elderly Age Weekend Edition Saturday 12/08/2012 -

Organized Crime and Terrorist Activity in Mexico, 1999-2002

ORGANIZED CRIME AND TERRORIST ACTIVITY IN MEXICO, 1999-2002 A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the United States Government February 2003 Researcher: Ramón J. Miró Project Manager: Glenn E. Curtis Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540−4840 Tel: 202−707−3900 Fax: 202−707−3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://loc.gov/rr/frd/ Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Criminal and Terrorist Activity in Mexico PREFACE This study is based on open source research into the scope of organized crime and terrorist activity in the Republic of Mexico during the period 1999 to 2002, and the extent of cooperation and possible overlap between criminal and terrorist activity in that country. The analyst examined those organized crime syndicates that direct their criminal activities at the United States, namely Mexican narcotics trafficking and human smuggling networks, as well as a range of smaller organizations that specialize in trans-border crime. The presence in Mexico of transnational criminal organizations, such as Russian and Asian organized crime, was also examined. In order to assess the extent of terrorist activity in Mexico, several of the country’s domestic guerrilla groups, as well as foreign terrorist organizations believed to have a presence in Mexico, are described. The report extensively cites from Spanish-language print media sources that contain coverage of criminal and terrorist organizations and their activities in Mexico. -

Teritoriální Uspořádání Policejních Složek V Zemích Evropské Unie: Inspirace Nejen Pro Českou Republiku II – Belgie, Dánsko, Finsko, Francie, Irsko, Itálie1 Mgr

Teritoriální uspořádání policejních složek v zemích Evropské unie: Inspirace nejen pro Českou republiku II – Belgie, Dánsko, Finsko, Francie, Irsko, Itálie1 Mgr. Oldřich Krulík, Ph.D. Abstrakt Po teoretickém „úvodním díle“ se ke čtenářům dostává pokračování volného seriálu o teritoriálním uspořádání policejních sborů ve členských státech Evropské unie. Kryjí nebo nekryjí se „policejní“ (případně i „hasičské“, justiční či dokonce „zpravodajské“) regiony s regiony, vytýčenými v rámci státní správy a samosprávy? Je soulad těchto územních prvků možné považovat za výjimku nebo za pravidlo? Jsou členské státy Unie zmítány neustálými reformami horizontálního uspořádání policejních složek, nebo si tyto systémy udržují dlouhodobou stabilitu? Text se nejprve věnuje „starým členským zemím“ Unie, a to pěkně podle abecedy. Řeč tedy bude o Belgii, Dánsku, Finsku, Francii, Irsku a Itálii. Klíčová slova Policejní síly, územní správa, územní reforma, administrativní mezičlánky Summary After the theoretical “introduction” can the readers to continue with the series describing the territorial organisation of the police force in the Member States of the European Union. Does the “police” regions coincide or not-coincide with the regions outlined in the state administration and local governments? Can the compliance of these local elements to be considered as an exception or the rule? Are the European Union Member States tossed about by constant reforms of the horizontal arrangement of police, or these systems maintain long-term stability? The text deals firstly -

Exploring Mission Drift and Tension in a Nonprofit Work Integration Social Enterprise

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2017 Exploring Mission Drift and Tension in a Nonprofit orkW Integration Social Enterprise Teresa M. Jeter Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Organizational Behavior and Theory Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Teresa Jeter has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Gary Kelsey, Committee Chairperson, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Gloria Billingsley, Committee Member, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Joshua Ozymy, University Reviewer, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2017 Abstract Exploring Mission Drift and Tension in a Nonprofit Work Integration Social Enterprise by Teresa M. Jeter MURP, Ball State University, 1995 BS, Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis 1992 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Policy and Administration Walden University May 2017 Abstract The nonprofit sector is increasingly engaged in social enterprise, which involves a combination and balancing of social mission and business goals which can cause mission drift or mission tension. -

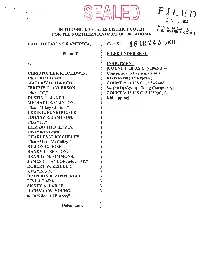

18 CR 2 4 5 JED ) Plaintiff, ) FILED UNDER SEAL ) V

-" ... F LED DEC 7 2018 Mark L VI IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT U S D . t cCartt, Clerk . /STA/CT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF OKLAHOMA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) Case No. 18 CR 2 4 5 JED ) Plaintiff, ) FILED UNDER SEAL ) v. ) INDICTMENT ) [COUNT 1: 18 U.S.C. § 1962(d) CHRISTOPHER K. BALDWIN, ) Conspiracy to Participate in a a/k/a "Fat Bastard," ) Racketeering Enterprise; MATHEW D. ABREGO, ) COUNT 2: 21 U.S.C. §§ 846 and JEREMY C. ANDERSON, ) 84l(b)(l)(A)(viii) - Drug Conspiracy; a/k/a "JC," ) COUNT 3: 18 U.S.C. § 1959(a)(l)- DUSTIN T. BAKER, ) Kidnapping] MICHAELE. CLINTON, ) a/k/a "Mikey Clinton," ) EDDIE L. FUNKHOUSER, ) JOHNNY R. JAMESON, ) a/k/a "JJ," ) ELIZABETH D. LEWIS, ) a/k/a "Beth Lewis," ) CHARLES M. MCCULLEY, ) a/k/a "Mark McCulley," ) DILLON R. ROSE, ) RANDY L. SEATON, ) BRANDY M. SIMMONS, ) JAMES C. TAYLOR, a/k/a "JT," ) ROBERT W. ZEIDLER, ) a/k/a "Rob Z," ) BRANDON R. ZIMMERLEE, ) LISA J. LARA, ) SISNEY A. LARGE, ) RICHARD W. YOUNG, ) a/k/a "Richard Pearce," ) ) Defendants. ) .• THE GRAND JURY CHARGES: COUNT ONE [18 u.s.c. § 1962(d)] INTRODUCTION 1. At all times relevant to this Indictment, the defendants, CHRISTOPHER K. BALDWIN, a/k/a "Fat Bastard" ("Defendant BALDWIN"), MATHEW D. ABREGO ("Defendant ABREGO"), JEREMY C. ANDERSON, a/k/a "JC" ("Defendant ANDERSON"), DUSTIN T. BAKER ("Defendant BAKER"), MICHAEL E. CLINTON, a/k/a "Mikey Clinton" ("Defendant CLINTON"), EDDIE L. FUNKHOUSER ("Defendant FUNKHOUSER"), JOHNNY R. JAMESON, a/k/a "JJ" ("Defendant JAMESON"), ELIZABETH D. -

Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests

Home Country of Origin Information Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests (RIR) are research reports on country conditions. They are requested by IRB decision makers. The database contains a seven-year archive of English and French RIR. Earlier RIR may be found on the European Country of Origin Information Network website. Please note that some RIR have attachments which are not electronically accessible here. To obtain a copy of an attachment, please e-mail us. Related Links • Advanced search help 15 August 2019 MEX106302.E Mexico: Drug cartels, including Los Zetas, the Gulf Cartel (Cartel del Golfo), La Familia Michoacana, and the Beltrán Leyva Organization (BLO); activities and areas of operation; ability to track individuals within Mexico (2017-August 2019) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada 1. Overview InSight Crime, a foundation that studies organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean (Insight Crime n.d.), indicates that Mexico’s larger drug cartels have become fragmented or "splintered" and have been replaced by "smaller, more volatile criminal groups that have taken up other violent activities" (InSight Crime 16 Jan. 2019). According to sources, Mexican law enforcement efforts to remove the leadership of criminal organizations has led to the emergence of new "smaller and often more violent" (BBC 27 Mar. 2018) criminal groups (Justice in Mexico 19 Mar. 2018, 25; BBC 27 Mar. 2018) or "fractur[ing]" and "significant instability" among the organizations (US 3 July 2018, 2). InSight Crime explains that these groups do not have "clear power structures," that alliances can change "quickly," and that they are difficult to track (InSight Crime 16 Jan. -

![Italian: Repubblica Italiana),[7][8][9][10] Is a Unitary Parliamentary Republic Insouthern Europe](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6369/italian-repubblica-italiana-7-8-9-10-is-a-unitary-parliamentary-republic-insouthern-europe-356369.webp)

Italian: Repubblica Italiana),[7][8][9][10] Is a Unitary Parliamentary Republic Insouthern Europe

Italy ( i/ˈɪtəli/; Italian: Italia [iˈtaːlja]), officially the Italian Republic (Italian: Repubblica italiana),[7][8][9][10] is a unitary parliamentary republic inSouthern Europe. Italy covers an area of 301,338 km2 (116,347 sq mi) and has a largely temperate climate; due to its shape, it is often referred to in Italy as lo Stivale (the Boot).[11][12] With 61 million inhabitants, it is the 5th most populous country in Europe. Italy is a very highly developed country[13]and has the third largest economy in the Eurozone and the eighth-largest in the world.[14] Since ancient times, Etruscan, Magna Graecia and other cultures have flourished in the territory of present-day Italy, being eventually absorbed byRome, that has for centuries remained the leading political and religious centre of Western civilisation, capital of the Roman Empire and Christianity. During the Dark Ages, the Italian Peninsula faced calamitous invasions by barbarian tribes, but beginning around the 11th century, numerous Italian city-states rose to great prosperity through shipping, commerce and banking (indeed, modern capitalism has its roots in Medieval Italy).[15] Especially duringThe Renaissance, Italian culture thrived, producing scholars, artists, and polymaths such as Leonardo da Vinci, Galileo, Michelangelo and Machiavelli. Italian explorers such as Polo, Columbus, Vespucci, and Verrazzano discovered new routes to the Far East and the New World, helping to usher in the European Age of Discovery. Nevertheless, Italy would remain fragmented into many warring states for the rest of the Middle Ages, subsequently falling prey to larger European powers such as France, Spain, and later Austria. -

Legacy, Vol. 17, 2017

2017 A Journal of Student Scholarship A Publication of the Sigma Kappa Chapter of Phi Alpha Theta A Publication of the Sigma Kappa & the Southern Illinois University Carbondale History Department & the Southern Illinois University Volume 17 Volume LEGACY • A Journal of Student Scholarship • Volume 17 • 2017 LEGACY Volume 17 2017 A Journal of Student Scholarship Editorial Staff Denise Diliberto Geoff Lybeck Gray Whaley Faculty Editor Hale Yılmaz The editorial staff would like to thank all those who supported this issue of Legacy, especially the SIU Undergradute Student Government, Phi Alpha Theta, SIU Department of History faculty and staff, our history alumni, our department chair Dr. Jonathan Wiesen, the students who submitted papers, and their faculty mentors Professors Jo Ann Argersinger, Jonathan Bean, José Najar, Joseph Sramek and Hale Yılmaz. A publication of the Sigma Kappa Chapter of Phi Alpha Theta & the History Department Southern Illinois University Carbondale history.siu.edu © 2017 Department of History, Southern Illinois University All rights reserved LEGACY Volume 17 2017 A Journal of Student Scholarship Table of Contents The Effects of Collegiate Gay Straight Alliances in the 1980s and 1990s Alicia Mayen ....................................................................................... 1 Students in the Carbondale, Illinois Civil Rights Movement Bryan Jenks ...................................................................................... 15 The Crisis of Legitimacy: Resistance, Unity, and the Stamp Act of 1765, -

Gang Project Brochure Pg 1 020712

Salt Lake Area Gang Project A Multi-Jurisdictional Gang Intelligence, Suppression, & Diversion Unit Publications: The Project has several brochures available free of charge. These publications Participating Agencies: cover a variety of topics such as graffiti, gang State Agencies: colors, club drugs, and advice for parents. Local Agencies: Utah Dept. of Human Services-- Current gang-related crime statistics and Cottonwood Heights PD Div. of Juvenile Justice Services historical trends in gang violence are also Draper City PD Utah Dept. of Corrections-- available. Granite School District PD Law Enforcement Bureau METRO Midvale City PD Utah Dept. of Public Safety-- GANG State Bureau of Investigation Annual Gang Conference: The Project Murray City PD UNIT Salt Lake County SO provides an annual conference open to service Salt Lake County DA Federal Agencies: providers, law enforcement personnel, and the SHOCAP Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, community. This two-day event, held in the South Salt Lake City PD Firearms, and Explosives spring, covers a variety of topics from Street Taylorsville PD United States Attorney’s Office Survival to Gang Prevention Programs for Unified PD United States Marshals Service Schools. Goals and Objectives commands a squad of detectives. The The Salt Lake Area Gang Project was detectives duties include: established to identify, control, and prevent Suppression and street enforcement criminal gang activity in the jurisdictions Follow-up work on gang-related cases covered by the Project and to provide Collecting intelligence through contacts intelligence data and investigative assistance to with gang members law enforcement agencies. The Project also Assisting local agencies with on-going provides youth with information about viable investigations alternatives to gang membership and educates Answering law-enforcement inquiries In an emergency, please dial 911. -

Law Enforcement Officials Perspectives on Gangs

LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICIALS PERSPECTIVES ON GANGS A Project Presented to the faculty of the Division of Social Work California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SOCIAL WORK by Arturo Velasco SPRING 2018 © 2018 Arturo Velasco ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICIALS PERSPECTIVES ON GANGS A Project by Arturo Velasco Approved by: , Committee Chair Jennifer Price-Wolf, PhD, MSW Date iii Student: Arturo Velasco I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the project. , Graduate Program Director Serge C. Lee, PhD Date Division of Social Work iv Abstract of LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICIALS PERSPECTIVES ON GANGS by Arturo Velasco The researcher performed face-to-face interviews with six selected law enforcement officials from different social service agencies in the City of Sacramento. There was found to be a measure of lack of understanding by law enforcement and gangs. The study was aimed to investigate the perceptions of community needs and awareness from both sides of the spectrum; and examine the relationship between the level of awareness of law enforcement and gangs. The author found four main themes within this research of law enforcement officials’ perspectives on gangs, these included lack of collaboration, negative influence at gangs’ homes, lack of positive exposure and lack of accountability. These findings suggest that law enforcement officials are not approaching youth gang members with a strength-based approach. Greater collaboration between law enforcement and social work could lead to better outcomes for gang-affiliated youth. -

Sean Patrick Griffin, Professor of Criminal Justice, Received His Ph.D

Sean Patrick Griffin, Professor of Criminal Justice, received his Ph.D. in the Administration of Justice (Sociology) from The Pennsylvania State University. Dr. Griffin, a former Philadelphia Police Officer, has authored peer-reviewed articles on the following topics: police legitimacy, police abuse of force, the social construction of white-collar crime, securities frauds, professional sports gambling, international narcotics trafficking and money laundering, political corruption, and organized crime. Dr. Griffin is the author of the critically-acclaimed text Philadelphia’s Black Mafia: A Social and Political History (Springer, 2003), and of the best-selling, more mainstream Black Brothers, Inc.: The Violent Rise and Fall of Philadelphia’s Black Mafia (Milo, 2005/2007). Each book is currently being/has been updated and revised to reflect historical events that have transpired since their respective initial publications. In 2007, Black Entertainment Television (BET) based an episode (“Philly Black Mafia: ‘Do For Self’”) of its popular “American Gangster” series on Black Brothers, Inc. Dr. Griffin was an interview subject and consultant for the episode, which is now re-broadcast on the History Channel and A&E Network, among others. Most recently, Professor Griffin authored the best-selling Gaming the Game: The Story Behind the NBA Betting Scandal and the Gambler Who Made It Happen (Barricade, 2011), which has been discussed in numerous academic and media forums. An ardent public scholarship advocate, Dr. Griffin commonly lends his expertise to an assortment of entities and individuals, including but not limited to: local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies (especially in re: organized crime, extortion, narcotics trafficking, tax evasion, and money laundering); regulatory agencies (especially in re: gaming and stock fraud); social service agencies (especially in re: policing and violence against women); and print, radio, and television outlets throughout the U.S. -

Eau Brummels of Gangland and the Killing They Did in Feuds Ho" It

1 9 -- THE SUN; SUNDAY, AtlGtlSTriSWi 1! eau Brummels of Gangland and the Killing They Did in Feuds ho" it v" A!. W4x 1WJ HERMAN ROSEHTHAL WHOSE K.1LLINQ- - POLICE COMMISSIOKER. EH RIGHT WHO IS IN $ MARKED T?e expressed great indignation that a KEEPING TJe GANGS SUBdECTIOK. BEGINNING-O- F crime had been committed. Ploggl .TAe stayed in. hiding for a few days whllo tho politicians who controlled the elec END FOR. tion services of the Five Points ar- ranged certain matters, and then ho Slaying of Rosenthal Marked the Be surrendered. Of courso ho pleaded e. ginning of the End for Gangs Whose "Biff" Ellison, who was sent to Sing Sing for his part In the killing of by Bill Harrington in Paul Kelly's New Grimes Had Been Covered a Brighton dive, came to the Bowery from Maryland when he was in his Crooked Politicians Some of WHERE early twenties. Ho got a Job' as ARTHUR. WOOD5P WHO PUT T5e GANGS bouncer in Pat Flynn's saloon in 34 Reformed THEY ObLUncr. Bond street, and advanced rapidly in Old Leaders Who tho estimation of gangland, because he was young and husky when he and zenship back Tanner Smith becamo as approaching tho end of his activities. hit a man that man went down and r 0 as anybody. Ho got Besides these there were numerous stayed down. That was how he got decent a citizen Murders Resulting From Rivalry Among Gangsters Were a Job as beef handler on the docks, other fights. bis nickname ho used to be always stevedore, and threatening to someone.