Legacy, Vol. 17, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of NYC”: The

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa B.A. in Italian and French Studies, May 2003, University of Delaware M.A. in Geography, May 2006, Louisiana State University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2014 Dissertation directed by Suleiman Osman Associate Professor of American Studies The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of the George Washington University certifies that Elizabeth Healy Matassa has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 21, 2013. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 Elizabeth Healy Matassa Dissertation Research Committee: Suleiman Osman, Associate Professor of American Studies, Dissertation Director Elaine Peña, Associate Professor of American Studies, Committee Member Elizabeth Chacko, Associate Professor of Geography and International Affairs, Committee Member ii ©Copyright 2013 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa All rights reserved iii Dedication The author wishes to dedicate this dissertation to the five boroughs. From Woodlawn to the Rockaways: this one’s for you. iv Abstract of Dissertation “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 This dissertation argues that New York City’s 1970s fiscal crisis was not only an economic crisis, but was also a spatial and embodied one. -

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0

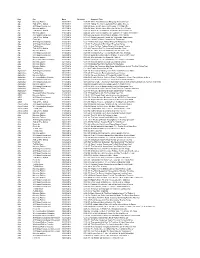

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0:04:09 When Should Seniors Hang Up The Car Keys? Age Talk Of The Nation 10/15/2012 0:30:20 Taking The Car Keys Away From Older Drivers Age All Things Considered 10/16/2012 0:05:29 Home Health Aides: In Demand, Yet Paid Little Age Morning Edition 10/17/2012 0:04:04 Home Health Aides Often As Old As Their Clients Age Talk Of The Nation 10/25/2012 0:30:21 'Elders' Seek Solutions To World's Worst Problems Age Morning Edition 11/01/2012 0:04:44 Older Voters Could Decide Outcome In Volatile Wisconsin Age All Things Considered 11/01/2012 0:03:24 Low-Income New Yorkers Struggle After Sandy Age Talk Of The Nation 11/01/2012 0:16:43 Sandy Especially Tough On Vulnerable Populations Age Fresh Air 11/05/2012 0:06:34 Caring For Mom, Dreaming Of 'Elsewhere' Age All Things Considered 11/06/2012 0:02:48 New York City's Elderly Worry As Temperatures Dip Age All Things Considered 11/09/2012 0:03:00 The Benefit Of Birthdays? Freebies Galore Age Tell Me More 11/12/2012 0:14:28 How To Start Talking Details With Aging Parents Age Talk Of The Nation 11/28/2012 0:30:18 Preparing For The Looming Dementia Crisis Age Morning Edition 11/29/2012 0:04:15 The Hidden Costs Of Raising The Medicare Age Age All Things Considered 11/30/2012 0:03:59 Immigrants Key To Looming Health Aide Shortage Age All Things Considered 12/04/2012 0:03:52 Social Security's COLA: At Stake In 'Fiscal Cliff' Talks? Age Morning Edition 12/06/2012 0:03:49 Why It's Easier To Scam The Elderly Age Weekend Edition Saturday 12/08/2012 -

Wings of War & Wings of Glory

WINGS OF WAR & WINGS OF GLORY World War 1 Complete Contents List 1. Wings of War: Famous Aces (2004) CONTENTS 5 player mats 2 rulers 1 "A" damage deck 4 manuever decks: A, B, C, & D 32 counters for tracking damage conditions 1 Rulebook 22 Airplane cards: SPAD XIII Captain Edward Vernon Rickenbacker 94th Aerosquadron U.S. Air Service SPAD XIII Capitano Fulco Ruffo di Calabria 91^ Squadriglia Regio Esercito SPAD XIII Capitaine René Paul Fonck Spa 103 Aviation Militaire SPAD XIII Capitaine Georges Guynemer Spa 3 Aviation Militaire SPAD XIII Maggiore Francesco Baracca 91^ Squadriglia Regio Esercito Albatros D.Va Leutnant Ludwig Weber Jasta 84 Luftstreitskräfte Albatros D.Va Leutnant Hans Böhning Jasta 79b Luftstreitskräfte Albatros D.Va Oberleutnant Ernst Udet Jasta 37 Luftstreitskräfte Albatros D.Va Vizefeldwebel Kurt Jentsch Jasta 61 Luftstreitskräfte Sopwith Camel Oberleutnant Otto Kissenberth Jasta 23 Luftstreitskräfte Sopwith Camel Flight Sub-Lieutenant Aubrey Beauclerk Ellwood 3 Naval Royal Naval Air Service Sopwith Camel Lieutenant Stuart Douglas Culley Experimental Centre of Martlesham Heath Royal Air Force Sopwith Camel Major William George Barker 66 Squadron Royal Flying Corps Sopwith Camel Lieutenant Jan Olieslagers 9me Escadrille de Chasse Aviation Militaire (Belgium) Fokker Dr.I Rittmeister Manfred von Richthofen Jasta 11 Luftstreitskräfte Fokker Dr.I Leutnant Fritz Kempf Jasta 2 “Boelcke” Luftstreitskräfte Fokker Dr.I Leutnant Arthur Rahn Jasta 19 Luftstreitskräfte Fokker Dr.I Leutnant Werner Voss Jasta 29 Luftstreitskräfte -

An Amazing 1969 Account of the Stonewall Uprising

An Amazing 1969 Account of the Stonewall Uprising GARANCE FRANKE- RUTA THE ATLANTIC JAN 24, 2013 Despite progress, the circumstances that gave rise to the rebellion that began the contemporary gay rights movement haven't changed as much as we might think. When President Obama briefly mentioned Stonewall during his Inaugural address, it prompted a lot of chatter about of the Stonewall riot and his historic adoption of the gay rights cause as his own. But what happened at the Stonewall Inn, really? New York papers tend to call it the Stonewall uprising, not the Stonewall riot, because it played out as six days of skirmishes between young gay, lesbian, and transgender individuals and the New York Police Department in the wake of a police raid of the Christopher Street bar in Manhattan's West Village. The raid came amid a broader police crackdown on gay bars for operating without N. Y. State Liquor Authority licenses, which was something they did only because the SLA refused to grant bars that served gays licenses, forcing them to operate as illegal saloons. Into that void stepped opportunists and Mafia affiliates, who ran the unlicensed establishments and reputedly had deals with the police to stay in business. But on the night of June 27, 1969, a police raid on the Stonewall involving the arrests of 13 people inside the bar met unexpected resistance when a crowd gathered and one of those arrested, a woman, cried out to the assembled bystanders as she was shoved into a paddy wagon, "Why don't you guys do something!" The conflict over the next six days played out as a very gay variant of a classic New York street rebellion. -

Zeppelins Over Trentham

Zeppelins over Trentham Zeppelin raids had taken place at points across the country from 1915, but it was believed that the Midlands were too far inland to be reached by airships. On 31st January 1916, the area was taken by surprise as a number of airships reached the Midlands. One was seen over Walsall at 20.10 and another attacked Burton at 20.30. Lighting restrictions were not in force at the time, so the local area, including the steelworks at Etruria, were lit up. A zeppelin approached from the south and was seen over Trentham. Frederick Todd, the Land Agent for the Trentham Estate, reported that: “At least two zeppelins, who were evidently making their way to Crewe, dropped seven bombs at Sideway Colliery without much damage - they missed their objectives which were the Power House, the by-products plant, and the pit-head installation.” They made craters, but caused no injuries or loss of life. Following this raid, precautions were taken, with blackouts and restrictions on lighting. In 1915 Trentham Church reported spending £3 on insurance against zeppelin attack and damage. On Monday 27th November 1916, a clear, dry night, the German Navy Airship LZ 61 [Tactical number L21], in the company of nine other Zeppelins, crossed the Yorkshire coast. It initially attacked Leeds but was repelled by anti-aircraft fire. Commanded by Oberleutnant Kurt Frankenberg, the LZ61 was on its 10th raid of England, and had also carried out 17 reconnaissance missions. At 22.45 a warning was received locally. Black out and air raid precautions were taken. -

THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors’ Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London

THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors’ Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors' Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London VIEWING Please note that bids should be ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES submitted no later than 16.00 Wednesday 9 December Motor Cars Monday to Friday 08:30 - 18:00 on Wednesday 9 December. 10.00 - 17.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5801 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Thereafter bids should be sent Thursday 10 December +44 (0) 20 7468 5802 fax directly to the Bonhams office at from 9.00 [email protected] Please see page 2 for bidder the sale venue. information including after-sale +44 (0) 8700 270 089 fax or SALE TIMES Motorcycles collection and shipment [email protected] Automobilia 11.00 +44 (0) 20 8963 2817 Motorcycles 13.00 [email protected] Please see back of catalogue We regret that we are unable to Motor Cars 14.00 for important notice to bidders accept telephone bids for lots with Automobilia a low estimate below £500. +44 (0) 8700 273 618 SALE NUMBER Absentee bids will be accepted. ILLUSTRATIONS +44 (0) 8700 273 625 fax 22705 New bidders must also provide Front cover: [email protected] proof of identity when submitting Lot 351 CATALOGUE bids. Failure to do so may result Back cover: in your bids not being processed. ENQUIRIES ON VIEW Lots 303, 304, 305, 306 £30.00 + p&p AND SALE DAYS (admits two) +44 (0) 8700 270 090 Live online bidding is IMPORTANT INFORMATION available for this sale +44 (0) 8700 270 089 fax BIDS The United States Government Please email [email protected] has banned the import of ivory +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 with “Live bidding” in the subject into the USA. -

When Did You Become Gay?

1 | AN INTRODUCTION TO WHAT I HEAR WHEN YOU SAY Deeply ingrained in human nature is a tendency to organize, classify, and categorize our complex world. Often, this is a good thing. This ability helps us make sense of our environment and navigate unfamiliar landscapes while keeping us from being overwhelmed by the constant stream of new information and experiences. When we apply this same impulse to social interactions, however, it can be, at best, reductive and, at worst, dangerous. Seeing each other through the lens of labels and stereotypes prevents us from making authentic connections and understanding each other’s experiences. Through the initiative, What I Hear When You Say ( WIHWYS ), we explore how words can both divide and unite us and learn more about the complex and everchanging ways that language shapes our expectations, opportunities, and social privilege. WIHWYS ’s interactive multimedia resources challenge what we think we know about race, class, gender, and identity, and provide a dynamic digital space where we can raise difficult questions, discuss new ideas, and share fresh perspectives. 1 | Introduction WHEN DID YOU BECOME GAY? if you don’t have an answer it doesn’t make you any less gay, it doesn’t make you any less queer or less trans be- “ cause we’re all evolving and we all change, and we don’t have this one day on our calendar where we suddenly understood everything. Kristin Russo, Activist / YouTube def•i•ni•tion of, relating to, or exhibiting sexual desire or behavior direct- GAY [gey] adjective ed toward a person or persons of one’s own sex. -

Comparison of Japanese and American Bankruptcy Law

Michigan Journal of International Law Volume 9 Issue 1 1988 Comparison of Japanese and American Bankruptcy Law Brooke Schumm III Miles & Stockbridge Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil Part of the Bankruptcy Law Commons, and the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Brooke Schumm III, Comparison of Japanese and American Bankruptcy Law, 9 MICH. J. INT'L L. 291 (1988). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil/vol9/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Journal of International Law at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Comparison of Japanese and American Bankruptcy Law Brooke Schumm III* I. INTRODUCTION A. Overview Japan has many fewer court-supervised insolvency proceedings than the United States. In Japan, a court may preclude a filing under the Corporate Reorganization Law based only on a brief pre-petition investigation, and thereby force the publicly-held corporation into a bankruptcy setting. The directors and officers may be individually liable for debts of the corporation without having signed personal guarantees. The Japanese martial and samurai traditions, and the consequent concern for family honor and pride, cause the Japanese to feel great shame and disgrace upon a failure such as a bankruptcy.' The bankruptcy laws reflect this disgrace in the lengthy period required for a fresh start. The outline and direction of this article are arranged approximately in the order of provisions under the U.S. -

View PDF File

LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER 2017 HERITAGE MONTH CITY OF LOS ANGELES LOS ANGELES CITY COUNCIL CULTURAL AFFAIRS Eric Garcetti Herb J. Wesson, Jr. COMMISSION Mayor District 10 Eric Paquette President Mike Feuer President Los Angeles City Attorney Gilbert Cedillo Charmaine Jefferson District 1 Ron Galperin Vice President Los Angeles City Controller Paul Krekorian Jill Cohen District 2 Thien Ho Bob Blumenfield Josefina Lopez District 3 Elissa Scrafano David Ryu John Wirfs District 4 Paul Koretz CITY OF LOS ANGELES District 5 DEPARTMENT OF Nury Martinez CULTURAL AFFAIRS District 6 Danielle Brazell Vacant General Manager District 7 Daniel Tarica Marqueece Harris-Dawson Assistant General Manager District 8 Will Caperton y Montoya Curren D. Price, Jr. Director of Marketing and Development District 9 Mike Bonin CALENDAR PRODUCTION District 11 Will Caperton y Montoya Mitchell Englander Editor and Art Director District 12 Marcia Harris Mitch O’Farrell PMAC District 13 Jose Huizar CALENDAR DESIGN District 14 Rubén Esparza, Red Studios Joe Buscaino PMAC District 15 Front Cover: Hector Silva, Los Novios, Pencil, colored pencil on 2 ply museum board, 22” x 28”, 2017 LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER 2017 HERITAGE MONTH ERIC GARCETTI MAYOR CITY OF LOS ANGELES Dear Friends, It is my pleasure to lead Los Angeles in celebrating Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Heritage Month and the immense contributions that our city’s LGBT residents make in the arts, academia, and private, public, and nonprofit sectors. I encourage Angelenos to take full advantage of this Calendar and Cultural Guide created by our Department of Cultural Affairs highlighting the many activities happening all over L.A. -

Old Heads Tell Their Stories: from Street Gangs to Street Organizations in New York City

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 412 305 UD 031 930 AUTHOR Brotherton, David C. TITLE Old Heads Tell Their Stories: From Street Gangs to Street Organizations in New York City. SPONS AGENCY Spencer Foundation, Chicago, IL. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 35p. PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adults; *Delinquency; Illegal Drug Use; *Juvenile Gangs; *Leadership; Neighborhoods; Role Models; Urban Areas; *Urban Youth IDENTIFIERS *New York (New York); Street Crime ABSTRACT It has been the contention of researchers that the "old heads" (identified by Anderson in 1990 and Wilson in 1987) of the ghettos and barrios of America have voluntarily or involuntarily left the community, leaving behind new generations of youth without adult role models and legitimate social controllers. This absence of an adult strata of significant others adds one more dynamic to the process of social disorganization and social pathology in the inner city. In New York City, however, a different phenomenon was found. Older men (and women) in their thirties and forties who were participants in the "jacket gangs" of the 1970s and/or the drug gangs of the 1980s are still active on the streets as advisors, mentors, and members of the new street organizations that have replaced the gangs. Through life history interviews with 20 "old heads," this paper traces the development of New York City's urban working-class street cultures from corner gangs to drug gangs to street organizations. It also offers a critical assessment of the state of gang theory. Analysis of the development of street organizations in New York goes beyond this study, and would have to include the importance of street-prison social support systems, the marginalization of poor barrio and ghetto youth, the influence of politicized "old heads," the nature of the illicit economy, the qualitative nonviolent evolution of street subcultures, and the changing role of women in the new subculture. -

Notes and References

Notes and References References to material in the Public Record Office are shown as 'PRO', with the class and piece number following. References to British Transport Commission papers are shown as 'BTC', with the file number following. These files are all from the former Chief Secretary's registry. The BTC's Annual Reports are indicated by 'AR', with the year and page number following. Minutes of the Executives are given their number, after the initials of the Executive concerned. Biographical notes are drawn chiefly from Who's Who and Who Was Who; from obituary notices in The Times; from the Dictionary ofNational Biography; from the transport technical journals, and from The Economist. 2 Drafting the Bill 1. Sir Norman Chester, The Nationalisation of British Industry, 1945-51 (London, 1975). 2. The Labour Party, Let Us Face the Future (London, 1945) p. 7. 3. Alfred Barnes (1887-1974) PC, MP. 'A designer by trade' (Who's Who). Educated Northampton Institute and LCC School of Arts and Crafts. MP (Labour/Co-op) for S.E. Ham, 1922-31 and 1935-55. A Lord Commissioner of the Treasury, 1929-30. Minister of War Transport and then Minister of Transport, 1945-51. Chairman of the Co-operative Party, 1924-45. Proprietor of the Eastcliffe Hotel, Walton-on-the-Naze. 'Made an important contribution to the development of the Co-operative movement as a political force ... shrewd business ability and much administrative skill ... He saw no point in needless rigidity. He was criticised by some Labour back-benchers for the measure of freedom of choice he left in the carriage of goods by road but that did not bother him .. -

Summer Library Events & Classes

Palm Springs We present another IMPORTANT MILESTONES IN HISTORY: IMPORTANT MILESTONES IN HISTORY: PUBLIC season of classes, films 50th Anniversary of the and lectures for you 50th Anniversary of the Stonewall Riots Apollo 11 Moon Landing Library to enjoy. We take your suggestions and areas The Stonewall riots (also referred of interest and try to to as the Stonewall uprising or create a lineup that the Stonewall rebellion) served J u n e – A u g u s t is diverse and as a catalyst for the gay rights entertaining, yet fulfills movement. In the early hours 2 0 1 9 the yearning to learn On July 20, 1969, America and the world new things. A more detailed description of of June 28, 1969, New York watched as Astronauts Neil Armstrong and our programs is available on our web site City police raided the Stonewall Buzz Aldrin took mankind’s first steps on the calendar but our brochure provides an Inn, a gay club located in Greenwich Village in lunar surface. This unprecedented engineering, overview of the quarter’s planned events so New York City. Armed with a warrant, police that you can mark your calendar and plan scientific, and political achievement, secured our officers entered the club, roughed up patrons, ahead. Stay up-to-date by subscribing to Nation’s leadership in space for generations to and arrested 13 people; including employees our monthly electronic newsletter. Tell your come. The national goal set in 1961 by President and people violating the state’s gender- friends and plan to attend; we look forward John F.