Understanding Neurotic Disorder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Phobias: Beaten by a Rod Or Instrument of Punishment, Or of # Being Severely Criticized — Rhabdophobia

Beards — Pogonophobia. List of Phobias: Beaten by a rod or instrument of punishment, or of # being severely criticized — Rhabdophobia. Beautiful women — Caligynephobia. 13, number — Triskadekaphobia. Beds or going to bed — Clinophobia. 8, number — Octophobia. Bees — Apiphobia or Melissophobia. Bicycles — Cyclophobia. A Birds — Ornithophobia. Abuse, sexual — Contreltophobia. Black — Melanophobia. Accidents — Dystychiphobia. Blindness in a visual field — Scotomaphobia. Air — Anemophobia. Blood — Hemophobia, Hemaphobia or Air swallowing — Aerophobia. Hematophobia. Airborne noxious substances — Aerophobia. Blushing or the color red — Erythrophobia, Airsickness — Aeronausiphobia. Erytophobia or Ereuthophobia. Alcohol — Methyphobia or Potophobia. Body odors — Osmophobia or Osphresiophobia. Alone, being — Autophobia or Monophobia. Body, things to the left side of the body — Alone, being or solitude — Isolophobia. Levophobia. Amnesia — Amnesiphobia. Body, things to the right side of the body — Anger — Angrophobia or Cholerophobia. Dextrophobia. Angina — Anginophobia. Bogeyman or bogies — Bogyphobia. Animals — Zoophobia. Bolsheviks — Bolshephobia. Animals, skins of or fur — Doraphobia. Books — Bibliophobia. Animals, wild — Agrizoophobia. Bound or tied up — Merinthophobia. Ants — Myrmecophobia. Bowel movements, painful — Defecaloesiophobia. Anything new — Neophobia. Brain disease — Meningitophobia. Asymmetrical things — Asymmetriphobia Bridges or of crossing them — Gephyrophobia. Atomic Explosions — Atomosophobia. Buildings, being close to high -

Adoring Our Wounds: Suicide, Prevention, and the Maya in Yucatán, México

Adoring Our Wounds: Suicide, Prevention, and the Maya in Yucatán, México By Beatriz Mireya Reyes-Cortes A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Stanley Brandes, Chair Professor William F. Hanks Professor Lawrence Cohen Professor William B. Taylor Spring 2011 Adoring our Wounds: Suicide, Prevention, and the Maya in Yucatán, México Copyright 2011 by Beatriz Mireya Reyes-Cortes Abstract Adoring Our Wounds: Suicide, Prevention, and the Maya in Yucatán, México By Beatriz Mireya Reyes-Cortes Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Stanley S. Brandes The first decade of the 21st century has seen a transformation in national and regional Mexican politics and society. In the state of Yucatán, this transformation has taken the shape of a newfound interest in indigenous Maya culture coupled with increasing involvement by the state in public health efforts. Suicide, which in Yucatán more than doubles the national average, has captured the attention of local newspaper media, public health authorities, and the general public; it has become a symbol of indigenous Maya culture due to an often cited association with Ixtab, an ancient Maya ―suicide goddess‖. My thesis investigates suicide as a socially produced cultural artifact. It is a study of how suicide is understood by many social actors and institutions and of how upon a close examination, suicide can be seen as a trope that illuminates the complexity of class, ethnicity, and inequality in Yucatán. In particular, my dissertation –based on extensive ethnographic and archival research in Valladolid and Mérida, Yucatán, México— is a study of both suicide and suicide prevention efforts. -

What Are “Twelve-Step” Programs?

What are “Twelve-Step” Programs? Traditional Twelve-Step programs outline a course of action for recovering from an addiction whereby participants proceed through twelve core developmental stages. Twelve-Step programs are a form of self-help in which members of a fellowship struggling with the same problem support each other. The Twelve-Step program originated with Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) (http://aa.org). According to AA, the twelve steps are as follows: (1) We admitted we were powerless over alcohol—that our lives had become unmanageable. (2) Came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity. (3) Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him. (4) Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves. (5) Admitted to God, to ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs. (6) Were entirely ready to have God remove all these defects of character. (7) Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings. (8) Made a list of all persons we had harmed, and became willing tomake amends to them all. (9) Made direct amends to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others. (10) Continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly admitted it. (11) Sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God, as we understood Him, praying only for knowledge of His will for us and the power to carry that out. (12) Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these Steps, we tried to carry this message to alcoholics, and to practice these principles in all our affairs. -

Kaplan & Sadock's Study Guide and Self Examination Review In

Kaplan & Sadock’s Study Guide and Self Examination Review in Psychiatry 8th Edition ← ↑ → © 2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Philadelphia 530 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106 USA, LWW.com 978-0-7817-8043-8 © 2007 by LIPPINCOTT WILLIAMS & WILKINS, a WOLTERS KLUWER BUSINESS 530 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106 USA, LWW.com “Kaplan Sadock Psychiatry” with the pyramid logo is a trademark of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, including photocopying, or utilized by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the copyright owner, except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Materials appearing in this book prepared by individuals as part of their official duties as U.S. government employees are not covered by the above-mentioned copyright. Printed in the USA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sadock, Benjamin J., 1933– Kaplan & Sadock’s study guide and self-examination review in psychiatry / Benjamin James Sadock, Virginia Alcott Sadock. —8th ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7817-8043-8 (alk. paper) 1. Psychiatry—Examinations—Study guides. 2. Psychiatry—Examinations, questions, etc. I. Sadock, Virginia A. II. Title. III. Title: Kaplan and Sadock’s study guide and self-examination review in psychiatry. IV. Title: Study guide and self-examination review in psychiatry. RC454.K36 2007 616.890076—dc22 2007010764 Care has been taken to confirm the accuracy of the information presented and to describe generally accepted practices. However, the authors, editors, and publisher are not responsible for errors or omissions or for any consequences from application of the information in this book and make no warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the currency, completeness, or accuracy of the contents of the publication. -

The Evolution of Variability in Magic, Divination and Religion

THE EVOLUTION OF VARIABILITY IN MAGIC, DIVINATION AND RELIGION: A MULTI-LEVEL SELECTION ANALYSIS A Dissertation by CATHARINA LAPORTE Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Michael S. Alvard Committee Members, Jeffrey Winking D. Bruce Dickson Jane Sell Head of Department, Cynthia A. Werner December 2013 Major Subject: Anthropology Copyright 2013 Catharina Laporte ABSTRACT Religious behavior varies greatly both with-in cultures and cross-culturally. Throughout history, scientific scholars of religion have debated the definition, function, or lack of function for religious behavior. The question remains: why doesn’t one set of beliefs suit everybody and every culture? Using mixed methods, the theoretical logic of Multi-Level Selection hypothesis (MLS) which has foundations in neo-evolutionary theory, and data collected during nearly two years of field work in Macaé Brazil, this study asserts that religious variability exists because of the historic and dynamic relationship between the individual, the family, the (religious) group and other groups. By re-representing a nuanced version of Elman Service’s sociopolitical typologies together with theorized categories of religion proposed by J.G. Frazer, Anthony C. Wallace and Max Weber, in a multi-level nested hierarchy, I argue that variability in religious behavior sustains because it provides adaptive advantages and solutions to group living on multiple levels. These adaptive strategies may be more important or less important depending on the time, place, individual or group. MLS potentially serves to unify the various functional theories of religion and can be used to analyze why some religions, at different points in history, may attract and retain more adherents by reacting to the environment and providing a dynamic balance between what the individual needs and what the group needs. -

Author Study Tips a Chapter 22: Psychiatry the Combining Form Psych/O, Meaning Mind, Is a Useful Word Part. One Finds This Combi

Author Study Tips A Chapter 22: Psychiatry The combining form psych/o, meaning mind, is a useful word part. One finds this combining form in many interesting terms. In Greek mythology, Psyche was a young woman who loved and was loved by Eros (god of love and the son of Aphrodite). She was united with him after Aphrodite's jealousy was overcome. Psyche became the personification of the soul (the vital principle in humans related to thought, action, and emotion). The term psychedelic means characterized by hallucinations, altered perceptions, and awareness. A psychedelic is a drug, such as LSD or mescaline, which produces such effects (Greek deloun means to make visible). Here are other terms using the combining form psych/o. Psychic trauma is an emotional shock or injury that produces a lasting impression, especially on the subconscious mind. Causes of psychic trauma may be abuse or neglect in childhood. Psychotherapeutic sessions can help alleviate such psychic trauma. Psychoactive substances are drugs or other agents that affect mood, behavior, or thinking processes. Cannabis, commonly known as marijuana, is a psychoactive substance. Examples of other psychoactive substances are stimulants, such as amphetamines or speed, and sedatives, such as phenobarbital and Valium. Psychotropic medications are prescribed to treat a variety of mental illnesses (troph/o means to turn). Examples of psychotropic drugs are antianxiety and antipanic agents, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, hypnotics, and powerful antipsychotic or neuroleptic medications. Neuroleptic drugs such as phenothiazines treat symptoms of psychoses. The delusions and hallucinations of a patient with schizophrenia are treated with neuroleptic drugs such as Thorazine or Haldol. -

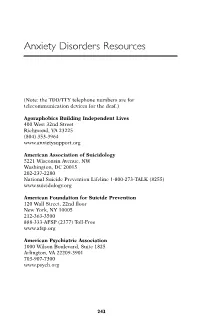

Anxiety Disorders Resources

Anxiety Disorders Resources (Note: the TDD/TTY telephone numbers are for telecommunication devices for the deaf.) Agoraphobics Building Independent Lives 400 West 32nd Street Richmond, VA 23225 (804) 353-3964 www.anxietysupport.org American Association of Suicidology 5221 Wisconsin Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20015 202-237-2280 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 1-800-273-TALK (8255) www.suicidology.org American Foundation for Suicide Prevention 120 Wall Street, 22nd floor New York, NY 10005 212-363-3500 888-333-AFSP (2377) Toll-Free www.afsp.org American Psychiatric Association 1000 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 1825 Arlington, VA 22209-3901 703-907-7300 www.psych.org 243 244 ANXIETY DISORDERS RESOURCES American Psychological Association 750 First Street, N.E. Washington, DC 20002-4242 800-374-2721 202-336-5500 TDD/TTY: 202-336-6213 www.apa.org Anxiety Disorders Association of America 8730 Georgia Avenue, Suite 600 Silver Spring, MD 20910 240-485-1001 www.adaa.org Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies 305 Seventh Avenue, 16th floor New York, NY 10001 (212) 647-1890 www.aabt.org Doctors Guide www.docguide.com Freedom from Fear 308 Seaview Avenue Staten Island, NY 10305 718-351-1717 www.freedomfromfear.org International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies 60 Revere Drive, Suite 500 Northbrook IL 60062 847-480-9028 www.istss.org MedlinePlus: Health Information www.medlineplus.gov Mental Health America (formerly National Mental Health Association) 2000 N. Beauregard St., 6t floor Alexandria, VA 22311 800-969-6MHA (6642) 703-684-7722 TTY: 800-433-5959 www.mentalhealthamerica.net ANXIETY DISORDERS RESOURCES 245 National Alliance for the Mentally Ill Colonial Place Three 2107 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 300 Arlington, VA 22201-3042 800-950-NAMI (6264) 703-524-7600 TDD: 703-516-7227 www.nami.org National Anxiety Foundation 3135 Custer Drive Lexington, KY 40517-4001 606-272-7166 National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder U.S. -

List of Phobias and Simple Cures.Pdf

Phobia This article is about the clinical psychology. For other uses, see Phobia (disambiguation). A phobia (from the Greek: φόβος, Phóbos, meaning "fear" or "morbid fear") is, when used in the context of clinical psychology, a type of anxiety disorder, usually defined as a persistent fear of an object or situation in which the sufferer commits to great lengths in avoiding, typically disproportional to the actual danger posed, often being recognized as irrational. In the event the phobia cannot be avoided entirely the sufferer will endure the situation or object with marked distress and significant interference in social or occupational activities.[1] The terms distress and impairment as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR) should also take into account the context of the sufferer's environment if attempting a diagnosis. The DSM-IV-TR states that if a phobic stimulus, whether it be an object or a social situation, is absent entirely in an environment - a diagnosis cannot be made. An example of this situation would be an individual who has a fear of mice (Suriphobia) but lives in an area devoid of mice. Even though the concept of mice causes marked distress and impairment within the individual, because the individual does not encounter mice in the environment no actual distress or impairment is ever experienced. Proximity and the degree to which escape from the phobic stimulus should also be considered. As the sufferer approaches a phobic stimulus, anxiety levels increase (e.g. as one gets closer to a snake, fear increases in ophidiophobia), and the degree to which escape of the phobic stimulus is limited and has the effect of varying the intensity of fear in instances such as riding an elevator (e.g. -

Father Ed Dowling — Page 1

CHESNUT — FATHER ED DOWLING — PAGE 1 May 1, 2015 Father Ed Dowling CHESNUT — FATHER ED DOWLING — PAGE 2 Father Ed Dowling Bill Wilson’s Sponsor Glenn F. Chesnut CHESNUT — FATHER ED DOWLING — PAGE 3 QUOTES “The two greatest obstacles to democracy in the United States are, first, the widespread delusion among the poor that we have a de- mocracy, and second, the chronic terror among the rich, lest we get it.” Edward Dowling, Chicago Daily News, July 28, 1941. Father Ed rejoiced that in “moving therapy from the expensive clinical couch to the low-cost coffee bar, from the inexperienced professional to the informed amateur, AA has democratized sani- ty.”1 “At one Cana Conference he commented, ‘No man thinks he’s ug- ly. If he’s fat, he thinks he looks like Taft. If he’s lanky, he thinks he looks like Lincoln.’”2 Edward Dowling, S.J., of the Queen’s Work staff, says, “Alcohol- ics Anonymous is natural; it is natural at the point where nature comes closest to the supernatural, namely in humiliations and in consequent humility. There is something spiritual about an art mu- seum or a symphony, and the Catholic Church approves of our use of them. There is something spiritual about A.A. too, and Catholic participation in it almost invariably results in poor Catholics be- coming better Catholics.” Added as an appendix to the Big Book in 1955.3 CHESNUT — FATHER ED DOWLING — PAGE 4 “‘God resists the proud, assists the humble. The shortest cut to humility is humiliations, which AA has in abundance. -

And 'Cultural Adaptation'

SPECIAL ARTICLES Anderson & Garcia Spirituality and cultural adaptation ‘Spirituality’ and ‘cultural adaptation’ in a Latino mutual aid group for substance misuse and mental health Brian T. Anderson,1 Angela Garcia2 BJPsych Bulletin (2015), 39,191-195, doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.114.048322 1University of California, San Francisco, Summary A previously unknown Spanish-language mutual aid resource for 2 USA; Stanford University, Stanford, substance use and mental health concerns is available in Latino communities across USA the USA and much of Latin America. This kind of ‘4th and 5th step’ group is a Correspondence to Brian T. Anderson ‘culturally adapted’ version of the 12-step programme and provides empirical grounds ([email protected]) on which to re-theorise the importance of spirituality and culture in mutual aid First received 4 Jun 2014, accepted 28 Jul 2014 recovery groups. This article presents ethnographic data on this organisation. B 2015 The Royal College of Declaration of interest None. Psychiatrists. This is an open-access article published by the Royal College of Psychiatrists and distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/ 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Group Higher Power (a pseudonym, to protect confidenti- says: ‘The only requirement for being here is that you wish ality) is a mutual aid group in Northern California for to transcend the pain in your life, and to stop suffering’. Latinos with substance use problems and other mental Unlike in AA, CQ members may identify as an health concerns. -

DMHAS Acronym List

Acronym List -A- AA Alcoholics Anonymous AAMFT American Association of Marriage and Family Therapists AAMR American Association on Mental Retardation AAP Assertive Aftercare Program AATF Adults with Autism Task Force AATOD American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence AB Administrative Bulletin ABA Association Behavior Assistants ABD Aged, Blind, and Disabled ABE Adult Basic Education ACA Affordable Care Act ACA/ACOA Adult Children of Alcoholics ACLU American Civil Liberties Union ACO Accountable Care Organization ACSES Automated Child Support Enforcement System ACT Assertive Community Treatment ACTF Acute Care Task Force (DMHAS) ADA American Diabetes Association (OR) Americans with Disabilities Act ADAU Alcoholism & Drug Abuse Unit ADC Alternative Disposition Committee ADD Attention Deficit Disorder ADHD Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder ADL Activities of Daily Living ADM Alcohol, Drug Abuse (OR) Mental Disorders ADP Average Daily Population ADRC Aging & Disability Resource Connection AFC Adult Family Care AFDC Aid for Families with Dependent Children AG Attorney General AH Auditory Handicapped AHCPR Agency for Health Care Policy and Research AIA AIDS Initial Assessment AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome AII Alcohol Issues Index AIP Adult Intervention Program AKFC Ann Klein Forensic Center AL-ANON Support Group for Family Members of Alcoholics ALA-TEEN Support Group for Teenage Alcoholics ALD Assistive Listening Device ALS Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis AMA Against Medical Advice (OR) American Medical Association -

Fear Reduction Jeanette E

Cardinal Stritch University Stritch Shares Master's Theses, Capstones, and Projects 1-1-1979 Fear reduction Jeanette E. Coleman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.stritch.edu/etd Part of the Special Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Coleman, Jeanette E., "Fear reduction" (1979). Master's Theses, Capstones, and Projects. 553. https://digitalcommons.stritch.edu/etd/553 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by Stritch Shares. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses, Capstones, and Projects by an authorized administrator of Stritch Shares. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FEAR REDUCTION by Jeanette E. Coleman A RESEARCH PAPER Submitted in PARTIAL FULFILLMENT of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Education (Education of Learning Disabled Children) at the Cardinal Stritch College Milwaukee, Wisconsin 1979 Fear Reduction This research paper has been approved for the Graduate Committee of the Cardinal Stritch College by Fear Reduction i i Table of Contents Acknowledgments i i i Chapter I Introduction A. Definitions 2 B. Scope and limitations 3 C. Summary 4 Chapter II Review of Research 4 A. I nt rod uc t ion 4 B. Anxiety 5 c. Basic elements of systematic 6 desensitization D. Hierarchies 9 E. Implementation 10 F. Examples 11 G. School phobia 14 H. Modifications 18 Chapter Ill Summary 20 References 22 Appendixes A. Relaxation technique 26 B. list of phobias 29 Fear Reduction i i i Acknowledgments My gratitude goes to: Sister Johanna Flanagan who touched my 1 ife in a very special way.