RAS227 Proof 98..122

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School May 2017 Modern Mythologies: The picE Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature Sucheta Kanjilal University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kanjilal, Sucheta, "Modern Mythologies: The pE ic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6875 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Mythologies: The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature by Sucheta Kanjilal A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a concentration in Literature Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Gurleen Grewal, Ph.D. Gil Ben-Herut, Ph.D. Hunt Hawkins, Ph.D. Quynh Nhu Le, Ph.D. Date of Approval: May 4, 2017 Keywords: South Asian Literature, Epic, Gender, Hinduism Copyright © 2017, Sucheta Kanjilal DEDICATION To my mother: for pencils, erasers, and courage. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS When I was growing up in New Delhi, India in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, my father was writing an English language rock-opera based on the Mahabharata called Jaya, which would be staged in 1997. An upper-middle-class Bengali Brahmin with an English-language based education, my father was as influenced by the mythological tales narrated to him by his grandmother as he was by the musicals of Broadway impressario Andrew Lloyd Webber. -

Essay About India in Urdu

1 Essay About India In Urdu The literary council of the official Kannada language of the state and more than other 50 language organizations promoting Kannada language threatened state-wide protests against the Urdu bulletin. One missive written by a team of Hindu nationalists from Bhartendu Harishchandra and sent to Madan Mohan Malviya was a scathing attack on the supposed uselessness and alienness of Urdu in British India. A man in his 30s approached and sat beside me, initiating a conver- sation and introducing himself as an off-duty member of the Home Guard. I was unsure how to react to his remark, but he did not seem to be complaining or hostile on the contrary, he was in awe of discovering another set of sounds seemingly alien to him. What had gone wrong. Once again, I got the feeling that Urdu was being treated as alien to Delhi, just as in Patna, although in both places, it has the status of the second official language. The name of the famous emblematic railway station, Mughal Sarai, was metamorphosed into Deen Dyal Upadhya following a chilling fervor by nationalist extremists, just to name one major example. Known as Father of Modern Hindi, Lallu Lal set the tone for Sanskritized Hindi. The recruitment of Urdu teachers was subsequently postponed and exam papers were no longer available in Urdu for public primary schools in Rajasthan. In 2016, the same Rajasthan government removed Urdu author Ismat Chughtai from the Class VIII Hindi textbook. One example Rahman cited was Prem Sagar 1803 by Lallu Lal, in which Arabic and Persian words were purged. -

1506LS Eng.P65

1 AS INTRODUCED IN LOK SABHA Bill No. 92 of 2019 THE CONSTITUTION (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2019 By SHRI RAVI KISHAN, M.P. A BILL further to amend the Constitution of India. BE it enacted by Parliament in the Seventieth Year of the Republic of India as follows:— 1. This Act may be called the Constitution (Amendment) Act, 2019. Short title. 2. In the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution, entries 3 to 22 shall be re-numbered as Amendment entries 4 to 23, respectively, and before entry 4 as so re-numbered, the following entry shall of the Eighth Schedule. 5 be inserted, namely:— "3. Bhojpuri.". STATEMENT OF OBJECTS AND REASONS Bhojpuri language which originated in the Gangetic plains of India is a very old and rich language having its origin in the Sanskrit language. Bhojpuri is the mother tongue of a large number of people residing in Uttar Pradesh, Western Bihar, Jharkhand and some parts of Madhya Pradesh as well as in several other countries. In Mauritius, this language is spoken by a large number of people. It is estimated that around one hundred forty million people speak Bhojpuri. Bhojpuri films are very popular in the country and abroad and have deep impact on the Hindi film industry. Bhojpuri language has a rich literature and cultural heritage. The great scholar Mahapandit Rahul Sankrityayan wrote some of his work in Bhojpuri. There have been some other eminent writers of Bhojpuri like Viveki Rai and Bhikhari Thakur, who is popularly known as the “Shakespeare of Bhojpuri”. Some other eminent writers of Hindi such as Bhartendu Harishchandra, Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi and Munshi Premchand were deeply influenced by Bhojpuri literature. -

Download Book

PREMA-SAGARA OR OCEAN OF LOVE THE PREMA-SAGARA OR OCEAN OF LOVE BEING A LITERAL TRANSLATION OF THE HINDI TEXT OF LALLU LAL KAVI AS EDITED BY THE LATE PROCESSOR EASTWICK, FULLY ANNOTATED AND EXPLAINED GRAMMATICALLY, IDIOMATICALLY AND EXEGETICALLY BY FREDERIC PINCOTT (MEMBER OF THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY), AUTHOR OF THE HINDI ^NUAL, TH^AKUNTALA IN HINDI, TRANSLATOR OF THE (SANSKRIT HITOPADES'A, ETC., ETC. WESTMINSTER ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE & CO. S.W. 2, WHITEHALL GARDENS, 1897 LONDON : PRINTED BY GILBERT AND KIVJNGTON, LD-, ST. JOHN'S HOUSE, CLEKKENWELL ROAD, E.G. TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE IT is well known to aU who have given thought to the languages of India that the or Bhasha as Hindi, the people themselves call is the most diffused and most it, widely important language of India. There of the are, course, great provincial languages the Bengali, Marathi, Panjabi, Gujarat!, Telugu, and Tamil which are immense numbers of spoken by people, and a knowledge of which is essential to those whose lot is cast in the districts where are but the Bhasha of northern India towers they spoken ; high above them both on account of the all, number of its speakers and the important administrative and commercial interests which of attach to the vast stretch territory in which it is the current form of speech. The various forms of this great Bhasha con- of about stitute the mother-tongue eighty-six millions of people, a almost as as those of the that is, population great French and German combined and cover the empires ; they important region hills on the east to stretching from the Rajmahal Sindh on the west and from Kashmir on the north to the borders of the ; the south. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

List of Books Available on Calibre Software

LIST OF BOOKS AVAILABLE ON CALIBRE SOFTWARE (PLEASE CONTACT LIBRARY STAFF TO ACCESS CALIBRE) 1. 1.doc · Kamal Swaroop 2. 50 Volume RGS Journal Table of Contents s · Unknown 3. 1836 Asiatic Researches Vol 19 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 4. 1839 Asiatic Researches Vol 19 Part 2 : THE HISTORY, THE ANTIQUITIES, THE ARTS AND SCIENCES, AND LITERATURE ASIA . · Asiatic Society, Calcutta 5. 1839 Asiatic Researches Vol 19 Part 2 s+m · Unknown 6. 1840 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 8 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 7. 1840 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 8 Part 2 s+m · Unknown 8. 1840 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 9 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 9. 1856 JASB Index AR 19 to JASB 23 · Unknown 10. 1856 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 24 s+m · Unknown 11. 1862 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 30 s+m · Unknown 12. 1866 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 34 s+m · Unknown 13. 1867 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 35 s+m · Unknown 14. 1875 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 44 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 15. 1875 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 44 Part 2 s+m · Unknown 16. 1951-52.PMD · Unknown 17. 1952-53-(Final).PMD · Unknown 18. 1953-54.pmd · Unknown 19. 1954-55.pmd · Unknown 20. 1955-56.pmd · Unknown 21. 1956-57.pmd · Unknown 22. 1957-58(interim) 1957-58-1958-59 · Unknown 23. 62569973-Text-of-Justice-Soumitra-Sen-s-Defence · Unknown 24. ([Views of the East; Comprising] India, Canton, [And the Shores of the Red Sea · Robert Elliot 25. -

Contact-Induced Change: Processes of Borrowing in Urdu Language in India by Ilyas Khan Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 7, Issue 11, November-2016 162 ISSN 2229-5518 Contact-induced change: Processes of Borrowing in Urdu language in India By Ilyas khan Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India Abstract: This paper explores the inferences from the language contact phenomenon in India. The aim of this paper is to assess one of the mechanism i.e. borrowing in Urdu spoken in India. With due course of time significant numbers of borrowings have been incorporated by this language. Generally, people speaks English language when interacts with elite class, educated people and for their social needs. Where English is a global language and has influenced almost all languages of the world. In course of time it has borrowed words from English. I have attempted to find those words that is borrowed in Urdu form different source. During the last twenty-thirty years Urdu has continued to enrich its vocabulary from English. Keywords- Contact language,Contact induced change, Borrowing, Urdu language —————————— —————————— Introduction: Over hundreds years, Linguists have focused heavily on language change. First time, comparative methods had been used to contour the problems of language change. In this paper, I hope to contribute to this effort by presenting a formal model of a particular kind of drastic change, namely contact-induced change, and placing limits on when its past presence can be inferred fromIJSER synchronic evidence. The analogy always occurs in language change and borrowing. Contact induced change can happen when speakers of different languages come in contact. This is the type of contact- induced change that is most obvious and that has been best studied. -

Final Line Repeats the Opening Rhyme

Kāvyārth - Encounters with Hindi Poetry Rupert Snell, Hindi Urdu Flagship kavyarth.hindiurdu"agship.org — SERPENTINE ENTANGLEMENTS — Four poems in Kuṇḍaliyā Metre Here and there in the wide landscape of Braj Bhasha literature one encounters the serpent-metre called ‘kuṇḍaliyā’. It takes its name from kuṇḍalī, a coiled snake, because the stanza coils upon itself, with its last word or phrase repeating the first word or phrase. A further coil occurs in its third line, whose first foot repeats the second foot from its second line. Here is an ad hoc English lakṣaṇ verse to demonstrate the form (its repeats italicized): Heads ’n’ tails become as one in kuṇḍaliyā’s coils As serpentine entanglements reward the poet’s toils. Reward the poet’s toils now with praise in fullest part, For constantly he concentrates on his poetic art. Yet while our finer poetry the heart itself assails The artifice of kuṇḍaliyā only heads entails. My doggerel is a little unkind (and these days the critic is not supposed to criticise); and in fact my tendency to view this metre as lightweight – as a remote parallel to the limerick, perhaps – derives more from its primary exemplar Giridhar than to the broader contexts in which it occurs. We will look at two samples from Giridhar and from two other poets’ use of the metre in exegetical expansions of couplets by Biharilal. But first, a note on translation. Though all premodern Hindi poetry rhymes, using rhyme in translation is highly unfashionable, and the best-regarded translators of poetry from Indian languages avoid it assiduously. -

Hindustani: a British Stupidity

Chapter 4 Hindustani: A British Stupidity As if Muslim intervention spreading over many centuries was not enough, a creeping British intervention began before India could sort out its affairs after the decline of the Moghuls. In an unprecedented way, from an unprecedented direction, the British intervention proved to be against all historical experience of India. An intervention is an intervention, whatever the justification or whatever cap is put on its head. The sum total of an intervention is a damaged society. That it distorts human condition and disorients humanity making it vulnerable to manipulation and disconnecting it from its past is the least something one can say. The disconnect becomes so elusive that it becomes undetectable even by the most brilliant. Thinking outside the interventionist mode becomes impossible. Abnormality become the norm. The death and damage of normality is so pervasive that there hardly remains any one to mourn the loss. Becoming lost in the wilderness becomes normal. A distorted orientation fails a society or people at every step. The lives of those who try to come out of such a situation by struggling to pull along their people are at best mild statements because so much goes unreported. It is a question, what would have been the fate of Hindi with another hundred or so years of strident Muslim rule in India? Would Hindi have met the fate of Persian like its being Arabicized after the Muslim conquest of Iran? Perhaps not, Indian roots being too deep and widespread, perhaps a different stalemate of another type from the present would have emerged. -

Mahatmagandhi University Ma

MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY PRIYADARSHINI HILLS KOTTAYAM - 686560 RESTRUCTURED CURRICULUM FOR POSTGRADUATE PROGRAMME UNDER CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM (CSS) IN HINDI 1 (w.e.f 2012 admission) 2 MAHATMAGANDHI UNIVERSITY, KOTTAYAM M. A. (HINDI CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM-2011) (2012 ADMISSION) For Both Regular Studies and Private Candidates Objectives of the Course • To give a linguistic and functional orientation to the study of Language and Literature. • To provide detailed and thorough knowledge of the trends, movements and literary forms of Ancient and Modern Hindi literature. • To enable the students to develop communicative skills and socio cultural awareness. • To develop a comparative outlook towards Indian literature. • To familiarize the students with living forms of Hindi language. • To provide a comprehensive knowledge of the new literary forms, media writing, Electronic media and various new movements in creative writing Structure of the Syllabus There will be Four Semesters in the course. Each Semester comprises of Five Papers. The Structure of the syllabus will be as follows:- Abstract of the CSS Programme- M.A. Hindi S Hours Total Code Course Credit e /Week Hours m HN1PC01 P.C.-I Ancient Poetry 1 e (Prachin Aur Riti Kavya) s t 5 90 4 e r 1 HN1PC02 P.C.-II Prose 5 90 4 HN1PC03 P.C.-III History of Hindi literature- I (a) Aadikal 5 90 4 (b) Madhyakal HN1PC04 P.C.-IV Bhasha Vigyan 5 90 4 HN1PC05 P.C.-V Drama & Theatre 5 90 4 Total 25 450 20 S HN2PC06 P.C.-VI Ancient Poetry 2 5 90 4 e (Bakti kavya) m HN2PC07 P.C.-VII Fiction Upto 1950 e s t 5 90 4 e r 3 2 HN2PC08 P.C. -

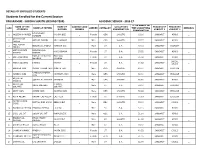

Students Enrolled for the Current Session PROGRAMME - SHIKSHA SHASTRI (SECOND YEAR) ACADEMIC SESSION - 2016-17

DETAILS OF ENROLLED STUDENTS Students Enrolled for the Current Session PROGRAMME - SHIKSHA SHASTRI (SECOND YEAR) ACADEMIC SESSION - 2016-17 % OF MARKS IN NAME OF THE NAME OF AADHAR CARD QUALIFYING PEADAGOGY PEDAGOGY S.N0 NAME OF FATHER GNEDER CATEGORY THE QUALIFYING REMARKS STUDENTS MOTHER NUMBER EXAMINATION SUBJECT 1 SUBJECT 2 EXAMINATION RIYAJUDDIN 1 AKLEEMA PARVEEN NADIRA BEE _ Female GEN SHASTRI 63.16 SANSKRIT HINDI _ KURESHI AMIT KUMAR 2 NATVAR PAREEK BRIJ KANWAR _ Male GEN SHASTRI 57.27 SANSKRIT HINDI _ PAREEK ANIL KUMAR 3 NIROTI LAL MEENA KUWANR BAI _ Male ST B.A. 47.83 SANSKRIT HISTORY _ MEENA ANITA KUMARI NARAYAN LAL 4 HUKI NINAMA _ Female ST B.A. 57.52 SANSKRIT HINDI _ NINAMA NINAMA RAMESH CHANDRA MANJULA 5 ANITA NANOMA _ Female ST B.A. 56.94 SANSKRIT HINDI _ NANOMA NANOMA SOCIAL 6 ANITA SOLANKI DHANJI KAMTU _ Female ST B.A. 50.52 SANSKRIT _ STUDY 7 ANURAG JAIN SUSHIL KUMAR JAIN SUNITA JAIN _ Male GEN SHASTRI 65.50 SANSKRIT ENGLISH _ YATENDRA KUMAR 8 APOORV JAIN PRATIBHA JAIN _ Male GEN SHASTRI 52.16 SANSKRIT ENGLISH _ JAIN ARJUN LAL 9 GOPAL LAL SHARMA SANTOSH _ Male GEN SHASTRI 58.50 SANSKRIT HINDI _ SHARMA ARJUN LAL CHAMPA 10 SOMA SOLANKI _ Male ST B.A. 53.47 SANSKRIT HISTORY _ SOLANKI SOLANKI 11 ARPIT JAIN ASHOK JAIN RACHNA JAIN _ Male GEN SHASTRI 58.22 SANSKRIT ENGLISH _ 12 ASHA MEENA BADARI LAL MEENA LALI DEVI _ Female ST SHASTRI 55.83 SANSKRIT ENGLISH _ ASHOK KUMAR 13 NATTHU RAM SAINI BEELA DEVI _ Male OBC SHASTRI 53.44 SANSKRIT CIVICS _ SAINI 14 BABOO LAL MEENA DHANRAJ MEENA LILA BAI _ Male ST B.A. -

The Languages of South Asia

THE LANGUAGES OF SOUTH ASIA a catalogue of rare books: dictionaries, grammars, manuals, & literature. with several important works on Tibetan Catalogue 31 John Randall (Books of Asia) John Randall (Books of Asia) [email protected] +44 (0)20 7636 2216 www.booksofasia.com VAT Number : GB 245 9117 54 Cover illustration taken from no. 4 (Colebrooke) in this catalogue; inside cover illustrations taken from no. 206 (Williams). © John Randall (Books of Asia) 2017 THE LANGUAGES OF SOUTH ASIA Catalogue 31 John Randall (Books of Asia) INTRODUCTION The conversion of the East India Company from trading concern to regional power South Asia, home to six distinct linguistic gave further impetus to the study of South families, remains one of the most Asian languages. Employees of the linguistically complex regions on earth. Company were charged with producing According to the 2001 Census of India, linguistic guides for official purposes. 1,721 languages and dialects were spoken as Military officers needed language skills to mother tongues. Of these, 29 had one issue commands to locally recruited troops. million or more speakers, and a further 31 And as the Company sought to perpetuate more than 100,000. the Mughal system of rule, knowledge of Persian as well as regional languages was The political implications of such dizzying essential for revenue collectors and diversity have been no less complex. Since administrators of justice. 1953, there have been many attempts to re- divide the country along linguistic lines. As All the while, some independent European recently as 2014, the new state of Telangana scholars demonstrated a genuine interest in was created as a homeland for Telugu and empathy for South Asian languages and speakers.