Pennae Atrae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carmina Burana

JANÁČKOVA AKADEMIE MÚZICKÝCH UMĚNÍ V BRNĚ Hudební fakulta Katedra kompozice, dirigování a operní režie Studijní obor Dirigování orchestru Carl Orff: Carmina Burana Diplomová práce Autor práce: MgA. Marek Prášil Vedoucí práce: prof. Mgr. Jan Zbavitel Oponent práce: doc. Mgr. Emil Skoták Brno 2017 Bibliografický záznam PRÁŠIL, Marek. Carl Orff: Carmina Burana [Carl Orff: Carmina Burana]. Brno: Janáčkova akademie múzických umění v Brně, Hudební Fakulta, Katedra kompozice, dirigování a operní režie, rok 2017, s.58 Vedoucí diplomové práce prof. Mgr. Jan Zbavitel. Anotace Diplomová práce „Carl Orff: Carmina Burana“, jak již ze samotného názvu vyplývá, pojednává o skladateli Carlu Orffovi a jeho nejslavnější skladbě, kantátě Carmina Burana. V první části shrnuje život skladatele, stručně charakterizuje jeho dílo a kompoziční styl. Druhá část, věnovaná samotné kantátě, je zaměřena především na srovnání několika verzí kantáty. Jedná se o původní originální symfonickou verzi, autorizovanou komorní verzi, a pak také o transkripci pro symfonický dechový orchestr. Annotation The thesis „Carl Orff: Carmina Burana” deals with composer Carl Orff and his most famous composition the cantata of Carmina Burana, as is already clear from the title itself. In the first part the composer's life is summarized and briefly his work and compositional style are characterized. The second part is dedicated to the cantata itself, it is focused on comparing several versions of the cantatas. There is one original symphonic version, the Authorized chamber version, and a transcription for symphonic band. Klíčová slova Carl Orff, Carmina Burana, kantáta, symfonický orchestr, dechový orchestr, komorní ansámbl Keywords Carl Orff, Carmina Burana, cantata, symphonic orchestra, wind band (concert band), chamber ensemble Poděkování Na tomto místě bych rád poděkoval především MgA. -

Concert: Carmina Burana by Carl Orff Ithaca College Choral Union

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 4-17-2005 Concert: Carmina Burana by Carl Orff Ithaca College Choral Union Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra Lawrence Doebler Jeffrey Grogan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ithaca College Choral Union; Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra; Doebler, Lawrence; and Grogan, Jeffrey, "Concert: Carmina Burana by Carl Orff" (2005). All Concert & Recital Programs. 4790. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/4790 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. ITHACA COLLEGE CHORAL UNION ITHACA COLLEGE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Lawrence Doebler, conductor CARMINA BURANA by Carl Orff Randie Blooding, baritone Deborah Montgomery-Cove, soprano Carl Johengen, tenor Ithaca College Women's Chorale, Janet Galvan, conductor Ithaca College Chorus, Janet Galvan, conductor Ithaca College Choir, Lawrence Doebler, conductor Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra, Jeffrey Grogan, conductor Charis Dimaris and Read Gainsford, pianists Members of the Ithaca Children's Choir Community School of Music and Arts Janet Galvan, artistic director Verna Brummett, conductor Ford Hall Sunday, April 17, 2005 4:00 p.m. ITHACA THE OVERTURE TO THE SCHOOL FOR SCANDAL Samuel Barber Ithaca College Symphony -

Carmina Burana

Carmina Burana Featuring the Choir and Percussion Ensembles of the Department of Music at the Université de Moncton; Monique Richard, conductor; Indian River Festival Chorus; Kelsea McLean, conductor; Danika Lorèn, soprano; Jonathan MacArthur, tenor; Adam Harris, baritone; Peter Tiefenbach, piano; and Robert Kortgaard, piano Sunday, July 10, 7:30pm Fogarty’s Cover Stan Rogers, arr. by Ron Smail I Dreamed of Rain Jan Garrett, arr. by Larry Nickel Praise His Holy Name Keith Hampton Embarquement pour Cythere Francis Poulenc Catching Shadows Ivan Trevino Misa Criolla Ariel Ramirez INTERMISSION Carmina Burana Carl Orff Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi Fortune, Empress of the World 1. O Fortuna O Fortune 2. Fortune plango vulnera I lament the wounds that Fortune deals I. Primo vere In Spring 3. Veris leta facies The joyous face of Spring 4. Omnia Sol temperat All things are tempered by the Sun 5. Ecce gratum Behold the welcome Uf dem anger In the Meadow 6. Tanz Dance 7. Floret silva The forest flowers 8. Chramer, gip die varwe mir Monger, give me coloured paint 9. a) Reie Round dance b) Swaz hie gat umbe They who here go dancing around c) Chume, chum, geselle min Come, come, my dear companion d) Swaz hie gat umbe (reprise) They who here go dancing around 10. Were diu werlt alle min If the whole world were but mine II. In Taberna In the Tavern 11. Estuans interius Seething inside 12. Olim lacus colueram Once I swam in lakes 13. Ego sum abbas Cucaniensis I am the abbot of Cockaigne 14. In taberna quando sumus When we are in the tavern III. -

Of Music PROGRAM

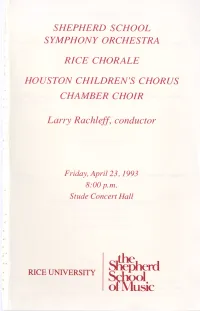

SHEPHERD SCHOOL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICE CHORALE HOUSTON CHILDREN'S CHORUS CHAMBER CHOIR Larry Rachleff, conductor Friday, April23, 1993 8:00p.m. Stude Concert Hall "-' sfkteherd RICE UNIVERSITY Sc~ol Of Music PROGRAM Fanfare for a Great City Arthur Gottschalk (b. 1952) Variations on a Theme of Joseph Haydn, Op. 56a Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) INTERMISSION Carmina Burana Carl Orff ( 1895-1982) Rice Chorale Houston Children's Chorus Chamber Choir Kelley Cooksey, soprano Francisco Almanza, tenor Robert Ames, baritone In consideration of the performers and members of the audience, please check audible paging devices with the ushers and silence audible timepieces. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are prohibited. SHEPHERD SCHOOL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Violin I Viola (cont.) Oboe Trumpet (cont.) Julie Savignon, Erwin Foubert Margaret Butler Troy Rowley concertmaster Patrick Horn Kyle Bruckmann David Workman Claudia Harrison Stephanie Griffin Jeffrey Champion Trombone Barbara Wittenberg Bin Sun Dione Chandler Wade Demmert Jeanine Tiemeyer Andrew Weaver Karen Friedman David Ford Kristin Lacey Sharon Neufeld ~ Brent Phillips Mihaela Oancea English Horn Cello Kyle Bruckmann Inga Ingver Tuba Katherine de Bethune, Yenn Chwen Er Clarinet Jeffrey Tomberg principal Yoong-han Chan Benjamin Brady Danny Urban ~ Jeanne Jaubert Magdalena Villegas Joanne Court Scott Brady Timpani and Tanya Schreiber Kelly Cramm Mary Ellen Morris Percussion Rebecca Ansel Martin van Maanen Robin Creighton Douglas Cardwell Eitan Ornoy X in-Yang Zhou Amy -

新古典主義(Neo-Classicism)與卡爾奧福(Carl Orff)的布蘭詩歌(Carmina

新古典主義(Neo-classicism)與卡爾奧福 (Carl Orff)的布蘭詩歌(Carmina Burana) 高千珊 目 次 目 次 ........................................................................................ I 前 言 ........................................................................................ 1 一、新古典主義音樂 .............................................................. 2 二、卡爾‧奧福的生平 .......................................................... 6 三、布蘭詩歌 ......................................................................... 10 四、結 語 ............................................................................. 25 參考資料 .................................................................................. 26 【附錄一】 ............................................................................. 29 I 前 言 卡爾‧奧福 ( Carl Burana , 1895-1982 ) 是 20 世紀著名的德國作曲家,更是 重要的音樂教育家,在他 87 年的音樂生涯中,透過長期的創作實踐與不斷的研 究探索,寫下許多著名的作品,而《布蘭詩歌》( Carmina Burana , 1937 ) 更是他 在音樂創作上一部重要的代表作。這部以中世紀詩歌為題材的大型作品,奧福將 中世紀、巴洛克及二十世紀這三個時空巧妙結合,以簡潔的節奏及特殊的音樂語 言創作出獨特的音樂風格。身為音樂老師的我,卡爾‧奧福這個名字早已十分熟 悉,但對於他的生平和他所處的時空背景,以及所創作的樂曲卻感到陌生,所以 本文將以此作為了解的重點,並試圖探究其作品《布蘭詩歌》。在結構上,本文 共分為四個部份,在第一部份中,本文將對二十世紀的新古典主義加以說明;第 二部份則針對卡爾‧奧福的生平做一介紹;第三部份則以《布蘭詩歌》為例,進 行分析與研究。 1 一、新古典主義音樂 十九世紀,科學的快速進步,電報、電話、錄音器材與無線電的發明,拉近 了東西方國家的距離,也間接增加對各民族間音樂的認識;而鐵路與汽車工業的 突飛猛進,也使經濟快速發展起來。進入二十世紀後,科技與工業持續進步,飛 機、汽車、收錄音機以及電話……等的普遍使用,將人們的生活徹底改變。自然 科學上,愛因斯坦的相對論及量子力學1的研究結果,則改變人們對物質結構的 概念以及對宇宙及世界的認知。而 1914 年的第一次世界大戰,使得許多國家經 歷社會與政治的動盪與不安,也改變了世界政治的權利結構。 西方音樂上,在歷經十九世紀浪漫主義音樂的洗禮,調性、和聲的使用達至 巔峰,社會與科技的發展與改變,也影響音樂家們去思索音樂未來的新方向。隨 著浪漫主義的式微,緊接而來的第一次世界大戰,使得新的生活型態及社會價值 漸漸形成,西方的文學、哲學、繪畫、舞蹈及音樂出現許多新的思潮,音樂的發 -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1995

osfon i^j^ny wksW Tangtew@» 5 NOW AT FILENE'S... FROM TOMMY H i The tommy collection i Cologne spray, 3.4-oz.,$42 Cologne spray, 1.7-oz.,$28 After-shave balmB mm 3.4-oz., $32 m After-shave, 3.4-oz., $32 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director One Hundred and Fourteenth Season, 1994-95 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. J. P. Barger, Chairman Nicholas T. Zervas, President Mrs. Edith L. Dabney, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson Nader F. Darehshori Edna S. Kalman Mrs. August R. Meyer Peter A. Brooke Deborah B. Davis Allen Z. Kluchman Mrs. Robert B. Newman James F. Cleary Nina L. Doggett Harvey Chet Peter C. Read John F. Cogan, Jr. Dean W. Freed Krentzman Carol Scheifele-Holmes Julian Cohen AvramJ. Goldberg George Krupp Richard A. Smith William F. Connell Thelma E. Goldberg R. Willis Leith, Jr. Ray Stata William M. Crozier, Jr. Julian T. Houston Trustees Emeriti Vernon R. Alden Archie C. Epps Mrs. George I. Mrs. George Lee Philip K. Allen Mrs. Harris Kaplan Sargent David B. Arnold, Jr. Fahnestock George H. Kidder Sidney Stoneman Leo L. Beranek Mrs. John L. Thomas D. Perry, Jr. John Hoyt Stookey Abram T. Collier Grandin Irving W. Rabb John L. Thorndike Nelson J. Darling, Jr. Other Officers of the Corporation John Ex Rodgers, Assistant Treasurer Michael G. McDonough, Assistant Treasurer Daniel R. Gustin, Clerk Board of Overseers of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Thelma E. Goldberg, Chairman Robert P. O'Block, Vice-Chairman Jordan L. -

Carmina Burana Masterworks Goes Wild'

Dr. Bryan Baker, Music Director & Conductor October Requiem Masterworks Celebrates Mozart June Carmina Burana Masterworks Goes Wild' * • t I Carmina Burana by CarlOrff and Invocation &, Dance by David Conte featuring Peninsula Cantare The Ragazzi Boys Chorus The Masterworks Orchestra and Soloists: Shawnette Sulker, soprano J. Raymond Meyers, tenor Ken Goodson, baritone Saturday June 2, 2007 8:00 pm Sunday June 3,20074:00 pm Carrington Hall at Sequoia High School Redwood City, CA Program Sexton Songs David Conte Her Kind Ringing the Bells Riding the Elevator into the Sky Us Shawnette Sulker, SOPRANO Bryan Baker, PIANO Invocation AND Dance David Conte I. Invocation II. Dance Janice Gunderson, CONDUCTOR Intermission Carmine Burana CarlOrff FORTUNA IMPERATRIX MUNDI 1. 0 Fortuna chorus 2. Fortune plango vulnera chorus PRIMO VERE 3. Veris leta facies chorus 4. Omni Sol temperat BARITONE SOLOIST 5. Ecce graturn chorus UF OEM ANGER 6. Tanz 7. Floret silva chorus 8. Chramer, gip die varwe mir SOPRANO SOLOIST 2 9. Reie Swaz hie gat umbe chorus Chume, chum geselle min chorus Swaz hie gat umbe chorus 10. Were diu werlt aIle min chorus INTABERNA 11. Estuans interius BARITONE SOlOIst 12. Olim lacus colueram TENOR SOLOIST 13. Ego sum abbas BARITONE SOLOIST 14. In taberna quando sumus chorus COUR D'AMOURS 15. Amor volat undique RAGAZZJ & SOPRANO SOLOIST 16. Dies, nox et omnia BARITONE SOLOIST 17. Stetit puella SOPRANO SOLOIST 18. Circa mea pectora BARHone SOLOIST 19. Si puer cum puellula chorus 20. Veni, veni, venias chorus 21. In trutina SOPRANO SOlOIst 22. Tempus est iocundum TUTTI 23. Dulcissime SOPRANO SOLOIST BLANZIFLORET HELENA 24. -

Carmina Burana

Lewisham Choral Society Orff: Carmina Burana John Joubert O Lorde, the maker of al thing Eric Whitacre Five Hebrew Love Songs Mozart Sonata for piano and violin in A Louise Kemény – Soprano Tim Travers-Brown – Countertenor Alex Ashworth – Baritone Sydenham High School Voices Director: Caroline Lenton-Ward Matthew Turner – Percussion leader Paula Muldoon – Violin Nico de Villiers and Jakob Fichert – Pianos Conductor: Dan Ludford-Thomas Cadogan Hall Saturday, 4 July 2015 A LITTLE QUIZ TO START.... Here's a little puzzle to start (no prizes I'm afraid!): what's the connection between the composers Pachelbel, Leoncavallo, Jeremiah Clarke, David Fanshawe, Dukas, Dohnányi and Orff? The answer: they're each really only known for a single composition. Carmina Burana by Carl Orff has established his name around the world and most people are likely to have heard at least extracts from it even without knowing what it was: apart from being one of the most performed and recorded works ever composed, extracts from it have provided the soundtrack to several films and TV programmes and been used to advertise everything from aftershave to beer, instant coffee and chocolate spread. It is said that every day at least one performance of Carmina Burana is being put on somewhere in the world. Earlier today two open air performances of the work were due to be given in Germany: in a quarry in Dossenheim, near Heidelberg and in Altenburg market place near Leipzig! Back in 1974 another performance hit the headlines. On an August night in the Royal Albert Hall the 80th season of the Henry Wood Proms was in full swing with a performance of the Orff. -

San Diego Symphony Orchestra a Jacobs Masterworks Concert

SAN DIEGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA A JACOBS MASTERWORKS CONCERT May 1, 2 and 3, 2015 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Piano Concerto No. 1 in C minor, Op. 35 Allegro moderat Lento Moderato Allegro con brio Conrad Tao, piano Micah Wilkinson, trumpet INTERMISSION CARL ORFF Carmina burana Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi O Fortuna Fortune plango vulnera I. Prima Vere Veris leta facies Omnia Sol temperat Edde gratium Uf dem anger Tanz Floret silva Chramer, gip die varwe mir Reie Swaz hie gat umbe Chume, chum, geselle min! Swaz hie gat umbe Were diu werlt alle min II. In Taberna Estuans interius Olim lacus colueram Ego sum abbas In taberna quando sumus III. Cours d’Amours Amor volat undique Dies, nox et omnia Stetit puella Circa mea pectora Si puer cum puellula Veni, veni, venias In trutina Tempus est locundum Dulcissime Blanziflor et Helena Ave formosissima Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi O fortuna Celena Shafer, soprano; Ryan Belongie, tenor; Tyler Duncan, baritone San Diego Master Chorale; San Diego Children’s Choir Program Notes Concerto No. 1 in C minor, Op. 35 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Born September 25, 1906, St. Petersburg Died August 9, 1975, Moscow Approx. 21 minutes Shostakovich’s First Piano Concerto dates from the spring of 1933, when the composer was 26. He wrote it just after completing his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, which would shortly get him into almost lethal trouble with Soviet authorities. Shostakovich, a virtuoso pianist whose playing was praised for its clarity and precision, was soloist at the concerto’s first performance (in Leningrad on October 15, 1933) and it should come as no surprise that the music is suited so exactly to those virtues. -

Rethinking the Carmina Burana (I): the Medieval Context and Modern Reception of the Codex Buranus

Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies • Rethinking the Carmina Burana (I): The Medieval Context and Modern Reception of the Codex Buranus Peter Godman Monumenta Germaniae Historica Munich, Germany Blanziflo˘r et Helena, Venus generosa! — Carmina Burana, no. 77 If this enchanting verse is known to a wider public, the credit is not due to medieval studies. Merit belongs to Carl Orff (1895 – 1982). The composer’s name seldom figures in studies of the Codex Buranus (Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, clm. 4660), and when it does, mention is desultory. Scholar- ship appears to shun the taint of what it regards as popularization. Readiness to consider the reception of the Codex Buranus over the longue durée is hardly perceptible, and the bird’s eye- view has produced few attempts to set one of the most celebrated manuscripts of the Middle Ages in its historical context. That is why the first part of this article, after a concise and selective account of pre- vious research, seeks to reconstruct the background against which the Codex Buranus was compiled. The second part explores the modern reception, both scholarly and “popular,” of the Carmina Burana on a broader basis than is customary. This essay is concerned with primary sources, and it employs the means of philology and paleography to raise methodological questions of cul- tural history. Such is the first step in a long and arduous journey toward a new edition of the Carmina Burana; criticism and correction are welcome. Perhaps, too, scholars of medieval studies will not shrink from the suggestion that they think again about one of the monuments of the discipline. -

Carmina Burana Carl Orff

Live & Free at the MAC | 2011–2012 Season Carmina Burana Carl Orff Robert Porco, Conductor Rainelle Krause, Soprano Jacob Williams, Tenor John Orduña, Baritone Oratorio Chorus Indiana University Children’s Choir University Orchestra Musical Arts Center Wednesday, April 18, 8:00 pm music.indiana.edu One Thousand Fifteenth Program of the 2011-12 Season _______________________ Indiana University Choral Department presents Carmina Burana by Carl Orff Robert Porco, Conductor Benjamin Geier, Assistant Conductor Piotr Wisniewski, Rehearsal Accompanist Katherine Strand, International Vocal Ensemble, Director Brian Schkeeper, IU Children’s Choir, Chorus Master Juan Hernandez, All-Campus Choir, Director Rainelle Krause, Soprano Jacob Williams, Tenor John Orduña, Baritone Oratorio Chorus University Orchestra _________________ Musical Arts Center Wednesday Evening April Eighteenth Eight O’Clock Carmina Burana (1935-36) Carl Orff (1895-1982) Fortuna imperatrix mundi Fortune, Empress of the World 1 O Fortuna – Chorus O Fortune 2 Fortune plango vulnera – Chorus I lament the wounds Fortune deals I – Primo vere In Spring 3 Veris leta facies – Small Chorus The joyous face of Spring 4 Omnia sol temperat – Baritone All things are tempered by the Sun 5 Ecce gratum – Chorus Behold the welcome Uf dem Anger In the Meadow 6 Tanz – Orchestra Dance 7 Floret silva – Chorus The forest flowers 8 Chramer, gip die varwe mir – Chorus Monger, give me colored paint 9 a) Reie – Orchestra Round dance 9 b) Swaz hie gat umbe – Chorus They who here go dancing around 9 c) Chume, -

Programme Concerts Mai, Juin 2014.Pdf

CONCERTS CARMINA BURANA Mai & Juin 2014 Direction Jacques PESI Soprane Frédérique VARDA Ténor Eric SALHA Baryton Jean-Philippe BIOJOUT Pianistes Julien OPIC & Stéphane TREBUCHET Percussions ENSEMBLE INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC@16 Professeurs et élèves CONSERVATOIRE GABRIEL FAURE Grand choeur CHORALES EN CHARENTE Chœur enfants ECOLE VICTOR HUGO D’ANGOULÊME CARMINA BURANA Carl Orff (1) O Fortuna ( O fortune )……………………………………………… 2:35 (2) Fortune plango vulnera ( Je pleure les blessures de la fortune ) 2:57 (3) Veris leta facies ( Les traits souriants du printemps )……………. 4:11 (4) Omnia sol temperat ( Le soleil tempère tout )……………………... 1:59 (5) Ecce gratum ( Voici le cher printemps )……………………………. 2:49 (6) Tanz ( Danse )…………………………………………………….….… 1:39 (7) Floret silva ( La noble forêt se couvre )……………………………... 3:17 (8) Chramer, gip die varwe mir ( Marchand, donnes-moi du fard )…. 3:10 (9b) Swaz hie gat umbe ( Celles qui tournent là en rond )……………... (9c) Chume, chum, geselle, min ( Viens, viens, cher amour ! )………. 4:51 (9d) Swaz hie gat umbe ( Celles qui tournent là en rond )……………… (10) Were diu werlt alle min ( Si tout l’univers était à moi )……………. 0:51 (11) Estuans intenus ( Dévoré de rage )………………………………….. 2:22 (12) Olm lacus colueram ( Jadis j’habitais le lac )……………………….. 3:40 (13) Ego sum abbas ( Je suis l’abbé )……………………………………. 1:29 (14) In taberna quando sumus ( Quand nous sommes à la taverne )... 3:08 (15) Amour volat undique ( L’amour vole partout )……………………... 3:04 (16) Dies, nox et omnia ( Jour, nuit et tout )………………………………. 2 :24 (17) Stetit puella ( Une jeune fille )…………………………………………. 1 :44 (18) Circa mea pectora ( Mon sein s’emplit )…………………………….. 2:01 (19) Si puer cum puellula ( Si un garçon avec une fille )………………..