SEASON BERNSTEIN Chichester Psalms for Chorus and Orchestra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

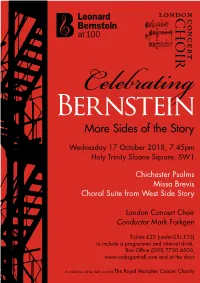

Bernsteincelebrating More Sides of the Story

BernsteinCelebrating More Sides of the Story Wednesday 17 October 2018, 7.45pm Holy Trinity Sloane Square, SW1 Chichester Psalms Missa Brevis Choral Suite from West Side Story London Concert Choir Conductor Mark Forkgen Tickets £25 (under-25s £15) to include a programme and interval drink. Box Office (020) 7730 4500, www.cadoganhall.com and at the door A collection will be held in aid of The Royal Marsden Cancer Charity One of the most talented and successful musicians in American history, Leonard Bernstein was not only a composer, but also a conductor, pianist, educator and humanitarian. His versatility as a composer is brilliantly illustrated in this concert to celebrate the centenary of his birth. The Dean of Chichester commissioned the Psalms for the 1965 Southern Cathedrals Festival with the request that the music should contain ‘a hint of West Side Story.’ Bernstein himself described the piece as ‘forthright, songful, rhythmic, youthful.’ Performed in Hebrew and drawing on jazz rhythms and harmonies, the Psalms Music Director: include an exuberant setting of ‘O be joyful In the Lord all Mark Forkgen ye lands’ (Psalm 100) and a gentle Psalm 23, ‘The Lord is my shepherd’, as well as some menacing material cut Nathan Mercieca from the score of the musical. countertenor In 1988 Bernstein revisited the incidental music in Richard Pearce medieval style that he had composed in 1955 for organ The Lark, Anouilh’s play about Joan of Arc, and developed it into the vibrant Missa Brevis for unaccompanied choir, countertenor soloist and percussion. Anneke Hodnett harp After three contrasting solo songs, the concert is rounded off with a selection of favourite numbers from Sacha Johnson and West Side Story, including Tonight, Maria, I Feel Pretty, Alistair Marshallsay America and Somewhere. -

LCOM182 Lent & Eastertide

LITURGICAL CHORAL AND ORGAN MUSIC Lent, Holy Week, and Eastertide 2018 GRACE CATHEDRAL 2 LITURGICAL CHORAL AND ORGAN MUSIC GRACE CATHEDRAL SAN FRANCISCO LENT, HOLY WEEK, AND EASTERTIDE 2018 11 MARCH 11AM THE HOLY EUCHARIST • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS LÆTARE Introit: Psalm 32:1-6 – Samuel Wesley Service: Collegium Regale – Herbert Howells Psalm 107 – Thomas Attwood Walmisley O pray for the peace of Jerusalem - Howells Drop, drop, slow tears – Robert Graham Hymns: 686, 489, 473 3PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CAMERATA Responses: Benjamin Bachmann Psalm 107 – Lawrence Thain Canticles: Evening Service in A – Herbert Sumsion Anthem: God so loved the world – John Stainer Hymns: 577, 160 15 MARCH 5:15PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS Responses: Thomas Tomkins Psalm 126 – George M. Garrett Canticles: Third Service – Philip Moore Anthem: Salvator mundi – John Blow Hymns: 678, 474 18 MARCH 11AM THE HOLY EUCHARIST • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS LENT 5 Introit: Psalm 126 – George M. Garrett Service: Missa Brevis – Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina Psalm 51 – T. Tertius Noble Anthem: Salvator mundi – John Blow Motet: The crown of roses – Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Hymns: 471, 443, 439 3PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CAMERATA Responses: Thomas Tomkins Psalm 51 – Jeffrey Smith Canticles: Short Service – Orlando Gibbons Anthem: Aus tiefer Not – Felix Mendelssohn Hymns: 141, 151 3 22 MARCH 5:15PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS Responses: William Byrd Psalm 103 – H. Walford Davies Canticles: Fauxbourdons – Thomas -

Seasons/08-09/Chichester Translation.Pdf

In 1965, Leonard Bernstein received a commission from the 1965 Southern Cathedral Festival to compose a piece for the cathedral choirs of Chichester, Winchester, and Salisbury. The result was the three-movement Chichester Psalms, a choral setting of a number of Hebrew psalm texts. This is Bernstein's version of church music: rhythmic, dramatic, yet fundamentally spiritual. The piece opens with the choir proclaiming Psalm 108, verse 2 (Awake, psaltery and harp!). This opening figure (particularly the upward leap of a minor seventh) recurs throughout the piece. The introduction leads into Psalm 100 (Make a joyful noise unto the Lord), a 7/4 dance that fits the joyous mood of the text. At times, this movement sounds like something out of West Side Story - it is percussive, with driving dance rhythms. The second movement starts with Psalm 23, with only a solo boy soprano and harp (suggesting David); the sopranos of the choir enter, repeating the solo melody. Suddenly and forcefully, the men interrupt in the middle of the Psalm 23 text (just after "Thy rod and thy staff, they comfort me") with Psalm 2. The setting of this text differs greatly from the flowing melodic feel of Psalm 23; it is evocative of the conflict in the text, with the men at times almost shouting. The men's voices gradually fade, and the initial peaceful melody returns (along with the rest of the Psalm 23 text), with the men continuing underneath. Movement 3 begins with an instrumental introduction based on the opening figure of the piece. The choir then enters with Psalm 131, set in a fluid 10/4 meter. -

Carl Orff Carmina Burana (1937)

CARL ORFF CARMINA BURANA (1937) CARL ORFF CARMINA BURANA (1937) CARMINA: Plural of Carmen, Latin for song. BURANA: Latin for, from Bayern, Bavaria. CANTATA VERSUS ORATORIO: Ø Cantata: A sacred or secular work for chorus and orchestra. Ø Oratorio: An opera without scenery or costumes. THE MUSIC: Ø A collection of 24 songs, most in Latin, some in Middle High German, with a few French words. THE SPECTACLE: Ø Seventy piece orchestra. Ø Large chorus of men, women and boys and girls. Ø Three soloists: tenor, baritone and soprano. THE POETRY: Ø The Medieval Latin poetry of Carmina Burana is in a style called Saturnian that dates back to 200 B.C. It was accented and stressed, used by soldiers on the march, tavern patrons and children at play. Later used by early Christians. Ø While the poems are secular, some are hymn-like. Orff’s arrangements highlight this. Ø The poems were composed by 13th century Goliards, Medieval itinerant street poets who lived by their wits, going from town to town, entertaining people for a few coins. Many were ex monks or university drop-outs. Ø Common Goliard themes include disaffection with society, mockery of the church, carnal desire and love. Ø Benedictine monks in a Bavarian monastery, founded in 733 in Beuern, in the Alps south of Munich, collected these Goliardic poems. Ø After the dissolution of the monastery in 1803, some two hundred of these poems were published in 1847 by Andreas Schmeller, a dialect scholar, in an anthology that he labeled Carmina Burana. Ø Orff discovered these in 1935 and, with the help of the poet Michael Hoffman, organized twenty-four poems from the collection into a libretto by the same name. -

Carmina Burana

JANÁČKOVA AKADEMIE MÚZICKÝCH UMĚNÍ V BRNĚ Hudební fakulta Katedra kompozice, dirigování a operní režie Studijní obor Dirigování orchestru Carl Orff: Carmina Burana Diplomová práce Autor práce: MgA. Marek Prášil Vedoucí práce: prof. Mgr. Jan Zbavitel Oponent práce: doc. Mgr. Emil Skoták Brno 2017 Bibliografický záznam PRÁŠIL, Marek. Carl Orff: Carmina Burana [Carl Orff: Carmina Burana]. Brno: Janáčkova akademie múzických umění v Brně, Hudební Fakulta, Katedra kompozice, dirigování a operní režie, rok 2017, s.58 Vedoucí diplomové práce prof. Mgr. Jan Zbavitel. Anotace Diplomová práce „Carl Orff: Carmina Burana“, jak již ze samotného názvu vyplývá, pojednává o skladateli Carlu Orffovi a jeho nejslavnější skladbě, kantátě Carmina Burana. V první části shrnuje život skladatele, stručně charakterizuje jeho dílo a kompoziční styl. Druhá část, věnovaná samotné kantátě, je zaměřena především na srovnání několika verzí kantáty. Jedná se o původní originální symfonickou verzi, autorizovanou komorní verzi, a pak také o transkripci pro symfonický dechový orchestr. Annotation The thesis „Carl Orff: Carmina Burana” deals with composer Carl Orff and his most famous composition the cantata of Carmina Burana, as is already clear from the title itself. In the first part the composer's life is summarized and briefly his work and compositional style are characterized. The second part is dedicated to the cantata itself, it is focused on comparing several versions of the cantatas. There is one original symphonic version, the Authorized chamber version, and a transcription for symphonic band. Klíčová slova Carl Orff, Carmina Burana, kantáta, symfonický orchestr, dechový orchestr, komorní ansámbl Keywords Carl Orff, Carmina Burana, cantata, symphonic orchestra, wind band (concert band), chamber ensemble Poděkování Na tomto místě bych rád poděkoval především MgA. -

Concert: Carmina Burana by Carl Orff Ithaca College Choral Union

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 4-17-2005 Concert: Carmina Burana by Carl Orff Ithaca College Choral Union Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra Lawrence Doebler Jeffrey Grogan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ithaca College Choral Union; Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra; Doebler, Lawrence; and Grogan, Jeffrey, "Concert: Carmina Burana by Carl Orff" (2005). All Concert & Recital Programs. 4790. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/4790 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. ITHACA COLLEGE CHORAL UNION ITHACA COLLEGE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Lawrence Doebler, conductor CARMINA BURANA by Carl Orff Randie Blooding, baritone Deborah Montgomery-Cove, soprano Carl Johengen, tenor Ithaca College Women's Chorale, Janet Galvan, conductor Ithaca College Chorus, Janet Galvan, conductor Ithaca College Choir, Lawrence Doebler, conductor Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra, Jeffrey Grogan, conductor Charis Dimaris and Read Gainsford, pianists Members of the Ithaca Children's Choir Community School of Music and Arts Janet Galvan, artistic director Verna Brummett, conductor Ford Hall Sunday, April 17, 2005 4:00 p.m. ITHACA THE OVERTURE TO THE SCHOOL FOR SCANDAL Samuel Barber Ithaca College Symphony -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 128, 2008-2009

* BOSTON SYAfl PHONY m ORCHESTRA i i , V SEASON f '0* 3' Music Director lk Conductor j Emei {Music Director Lc I IP the Clarendon BACK BAY The Way to Live ;; III! in"! I II !! U nil * I v l iji HI I etc - I y=- • ^ Fi 2 '\ i ra % m 1 1 ih ... >'? & !W ||RBIK;| 4* i :: it n w* n- I II " n ||| IJH ? iu u. I 1?: iiir iu» !! i; !l! Hi \m SL • i= ! - I m, - ! | || L ' RENDERING BY NEOSCAPE INTRODUCING FIVE STAR LIVING™ WITH UNPRECEDENTED SERVICES AND AMENITIES DESIGNED BY ROBERT A.M. STERN ARCHITECTS, LLP ONE TO FOUR BEDROOM LUXURY CONDOMINIUM RESIDENCES STARTING ON THE 15TH FLOOI CORNER OF CLARENDON AND STUART STREETS THE CLARENDON SALES AND DESIGN GALLERY, 14 NEWBURY STREET, BOSTON, MA 617.267.4001 www.theclarendonbackbay.com BRELATED DL/aLcomp/ REGISTERED W "HE U.S. GREEN BUILDING COUNl ITH ANTICIPATED LEED SILVER CERTIFICATION The artist's rendering shown may not be representative of the building. The features described and depicted herein are based upon current development plans, which a described. No Fede: subject to change without notice. No guarantee is made that said features will be built, or, if built, will be of the same type, size, or nature as depicted or where prohibited. agency has judged the merits or value, if any, of this property. This is not an offer where registration is required prior to any offer being made. Void Table of Contents | Week 7 15 BSO NEWS 21 ON DISPLAY IN SYMPHONY HALL 23 BSO MUSIC DIRECTOR JAMES LEVINE 26 THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 31 THIS WEEK'S PROGRAM Notes on the Program 35 The Original Sound of the "Carmina burana" (c.1230) 41 Carl Orff's "Carmina burana" 53 To Read and Hear More.. -

Composition Catalog

1 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 New York Content & Review Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. Marie Carter Table of Contents 229 West 28th St, 11th Floor Trudy Chan New York, NY 10001 Patrick Gullo 2 A Welcoming USA Steven Lankenau +1 (212) 358-5300 4 Introduction (English) [email protected] Introduction 8 Introduction (Español) www.boosey.com Carol J. Oja 11 Introduction (Deutsch) The Leonard Bernstein Office, Inc. Translations 14 A Leonard Bernstein Timeline 121 West 27th St, Suite 1104 Straker Translations New York, NY 10001 Jens Luckwaldt 16 Orchestras Conducted by Bernstein USA Dr. Kerstin Schüssler-Bach 18 Abbreviations +1 (212) 315-0640 Sebastián Zubieta [email protected] 21 Works www.leonardbernstein.com Art Direction & Design 22 Stage Kristin Spix Design 36 Ballet London Iris A. Brown Design Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited 36 Full Orchestra Aldwych House Printing & Packaging 38 Solo Instrument(s) & Orchestra 71-91 Aldwych UNIMAC Graphics London, WC2B 4HN 40 Voice(s) & Orchestra UK Cover Photograph 42 Ensemble & Chamber without Voice(s) +44 (20) 7054 7200 Alfred Eisenstaedt [email protected] 43 Ensemble & Chamber with Voice(s) www.boosey.com Special thanks to The Leonard Bernstein 45 Chorus & Orchestra Office, The Craig Urquhart Office, and the Berlin Library of Congress 46 Piano(s) Boosey & Hawkes • Bote & Bock GmbH 46 Band Lützowufer 26 The “g-clef in letter B” logo is a trademark of 47 Songs in a Theatrical Style 10787 Berlin Amberson Holdings LLC. Deutschland 47 Songs Written for Shows +49 (30) 2500 13-0 2015 & © Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. 48 Vocal [email protected] www.boosey.de 48 Choral 49 Instrumental 50 Chronological List of Compositions 52 CD Track Listing LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 2 3 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 A Welcoming Leonard Bernstein’s essential approach to music was one of celebration; it was about making the most of all that was beautiful in sound. -

FRENCH SYMPHONIES from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

FRENCH SYMPHONIES From the Nineteenth Century To The Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman NICOLAS BACRI (b. 1961) Born in Paris. He began piano lessons at the age of seven and continued with the study of harmony, counterpoint, analysis and composition as a teenager with Françoise Gangloff-Levéchin, Christian Manen and Louis Saguer. He then entered the Paris Conservatory where he studied with a number of composers including Claude Ballif, Marius Constant, Serge Nigg, and Michel Philippot. He attended the French Academy in Rome and after returning to Paris, he worked as head of chamber music for Radio France. He has since concentrated on composing. He has composed orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. His unrecorded Symphonies are: Nos. 1, Op. 11 (1983-4), 2, Op. 22 (1986-8), 3, Op. 33 "Sinfonia da Requiem" (1988-94) and 5 , Op. 55 "Concerto for Orchestra" (1996-7).There is also a Sinfonietta for String Orchestra, Op. 72 (2001) and a Sinfonia Concertante for Orchestra, Op. 83a (1995-96/rév.2006) . Symphony No. 4, Op. 49 "Symphonie Classique - Sturm und Drang" (1995-6) Jean-Jacques Kantorow/Tapiola Sinfonietta ( + Flute Concerto, Concerto Amoroso, Concerto Nostalgico and Nocturne for Cello and Strings) BIS CD-1579 (2009) Symphony No. 6, Op. 60 (1998) Leonard Slatkin/Orchestre National de France ( + Henderson: Einstein's Violin, El Khoury: Les Fleuves Engloutis, Maskats: Tango, Plate: You Must Finish Your Journey Alone, and Theofanidis: Rainbow Body) GRAMOPHONE MASTE (2003) (issued by Gramophone Magazine) CLAUDE BALLIF (1924-2004) Born in Paris. His musical training began at the Bordeaux Conservatory but he went on to the Paris Conservatory where he was taught by Tony Aubin, Noël Gallon and Olivier Messiaen. -

Stéphane Denève, Conductor Yefim Bronfman, Piano Clémentine

Stéphane Denève, conductor Friday, February 15, 2019 at 8:00pm Yefim Bronfman, piano Saturday, February 16, 2019 at 8:00pm Clémentine Margaine, mezzo-soprano St. Louis Symphony Chorus Amy Kaiser, director PROKOFIEV Cinderella Suite (compiled by Stéphane Denève) (1940-1944) (1891-1953) Introduction Pas-de-chale Interrupted Departure Clock Scene - The Prince’s Variation Cinderella’s Arrival at the Ball - Grand Waltz Promenade - The Prince’s First Galop - The Father Amoroso - Cinderella’s Departure for the Ball - Midnight PROKOFIEV Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, op. 16 (1913) Andantino; Allegretto; Tempo I Scherzo: Vivace Intermezzo: Allegro moderato Finale: Allegro tempestoso Yefim Bronfman, piano INTERMISSION 23 PROKOFIEV Alexander Nevsky, op. 78 (1938) Russia under the Mongolian Yoke Song about Alexander Nevsky The Crusaders in Pskov Arise, ye Russian People The Battle on the Ice The Field of the Dead Alexander’s Entry into Pskov Clémentine Margaine, mezzo-soprano St. Louis Symphony Chorus Amy Kaiser, director ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The 2018/2019 Classical Series is presented by World Wide Technology and The Steward Family Foundation. Stéphane Denève is the Linda and Paul Lee Guest Artist. Yefim Bronfman is the Carolyn and Jay Henges Guest Artist. The concert of Friday, February 15, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Sally S. Levy. The concert of Saturday, February 16, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Ms. Jo Ann Taylor Kindle. The St. Louis Symphony Chorus is underwritten in part by the Richard E. Ashburner, Jr. Endowed Fund. The St. Louis Symphony Chorus is underwritten in part by the Edward Chase Garvey Memorial Foundation. -

Radio 3 Listings for 13 – 19 August 2011 Page 1 of 11 SATURDAY 13 AUGUST 2011 Swedish Radio Choir, Olov Olofsson (Piano), Eric Ericson Editor Sally Dunkley

Radio 3 Listings for 13 – 19 August 2011 Page 1 of 11 SATURDAY 13 AUGUST 2011 Swedish Radio Choir, Olov Olofsson (piano), Eric Ericson editor Sally Dunkley. In the library of Christchurch, Oxford (conductor) they uncover the Fanshawe manuscripts, one of the most SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b0132pt8) important collections of responses including the heartfelt and Jonathan Swain presents Mozart piano Concerti performed by 5:08 AM moving piece "Tis now Dead Night" by Thomas Ford, recently Clara Haskil Prokofiev, Sergey (1891-1953) reconstructed for performance by Gallicantus. Cinderella's waltz from (Cinderella) - suite no.1 (Op.107) 1:01 AM BBC Philharmonic, Vassily Sinaisky (conductor) Tristram also visits the National Portrait Gallery with its former Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus [1756-1791] director, historian Sir Roy Strong, who has been fascinated by Concerto for piano and orchestra no. 9 (K.271) in E flat major 5:14 AM Henry's life since the 1960s. At the gallery, they see portraits of Clara Haskil (piano) ORTF Orchestra, Igor Markevitch Ebner, Leopold (1769-1830) the dashing young prince, a small medallion of him portrayed Trio in B flat major like a Roman emperor and an etching of the hearse for his 1:33 AM Zagreb Woodwind Trio lavish funeral. It's impossible to ignore the parallels to Diana's Enescu, George (1881-1955) death. Romanian Rhapsody No.1 in A major (Op.11 no.1) 5:21 AM Romanian National Radio Orchestra, Horia Andreescu (cond) Vivaldi, Antonio (1678-1741) Cello concerto in G major (RV.413) SAT 13:00 The Early Music Show (b0137yz1) 1:45 AM Stefan Popov (cello), Sofia Soloists Chamber Ensemble, Emil York Early Music Festival 2011 Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus [1756-1791] Tabakov (conductor) Concerto for piano and orchestra no. -

Carmina Burana

Carmina Burana Featuring the Choir and Percussion Ensembles of the Department of Music at the Université de Moncton; Monique Richard, conductor; Indian River Festival Chorus; Kelsea McLean, conductor; Danika Lorèn, soprano; Jonathan MacArthur, tenor; Adam Harris, baritone; Peter Tiefenbach, piano; and Robert Kortgaard, piano Sunday, July 10, 7:30pm Fogarty’s Cover Stan Rogers, arr. by Ron Smail I Dreamed of Rain Jan Garrett, arr. by Larry Nickel Praise His Holy Name Keith Hampton Embarquement pour Cythere Francis Poulenc Catching Shadows Ivan Trevino Misa Criolla Ariel Ramirez INTERMISSION Carmina Burana Carl Orff Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi Fortune, Empress of the World 1. O Fortuna O Fortune 2. Fortune plango vulnera I lament the wounds that Fortune deals I. Primo vere In Spring 3. Veris leta facies The joyous face of Spring 4. Omnia Sol temperat All things are tempered by the Sun 5. Ecce gratum Behold the welcome Uf dem anger In the Meadow 6. Tanz Dance 7. Floret silva The forest flowers 8. Chramer, gip die varwe mir Monger, give me coloured paint 9. a) Reie Round dance b) Swaz hie gat umbe They who here go dancing around c) Chume, chum, geselle min Come, come, my dear companion d) Swaz hie gat umbe (reprise) They who here go dancing around 10. Were diu werlt alle min If the whole world were but mine II. In Taberna In the Tavern 11. Estuans interius Seething inside 12. Olim lacus colueram Once I swam in lakes 13. Ego sum abbas Cucaniensis I am the abbot of Cockaigne 14. In taberna quando sumus When we are in the tavern III.