Carmina Burana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lehigh University Choral Arts Lehigh University Music Department

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Performance Programs Music Spring 5-3-2002 Lehigh University Choral Arts Lehigh University Music Department Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/cas-music-programs Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Lehigh University Music Department, "Lehigh University Choral Arts" (2002). Performance Programs. 155. http://preserve.lehigh.edu/cas-music-programs/155 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Programs by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BAKER HALL• ZOELLNERARTS CENTER . I I Lehigh Univer. ity Music Department 2001 - 2002 SEASON Welcome to Zoellner Arts Center! We hope you will take advantage of all the facilities, including Baker Hall, the Diamond and Black Box Theaters, as well as the Art Galleries and the Museum Shop. There are restrooms on every floor and concession stands in the two lobbies. For all ticket information, call (610) 7LU-ARTS (610-758-2787). To ensure the best experience for everyone, please: Bring no food or drink into any of the theaters Refrain from talking while music is being performed Refrain from applause between movements Do not use flash photography or recording devices Turn off all pagers and cellular phones Turn off alarms on wrist watches Do not smoke anywhere in the facilities MUSIC DEPARTMENT STAFF Professors - Paul Salemi, Steven Sametz, Nadine Sine (chair) -

Carmina Burana

The William Baker Choral Foundation in the Midwest Presents Carl Orff CARMINA BURANA The Summer Singers of Kansas City William O. Baker, Music Director & Conductor Christine Freeman, Associate Music Director Jamea J. Sale, WBCF Executive Associate Music Director Niccole Winney, Student Intern Steven McDonald & Robert Pherigo, Piano Mark Lowry, John Currey, Ray DeMarchi Steve Riley & Laura Lee Crandall, Percussion Sarah Tannehill Anderson, soprano David Adams, tenor Robert McNichols, baritone Sunday Afternoon, 19 August 2018 Grace & Holy Trinity Cathedral Kansas City, Missouri www.ChoralFoundation.org The 20th Anniversary Summer Singers of Kansas City William O. Baker, DMA Sharon Abner Barbara Gustin Ruth Ann Phares WBCF Founder & Music Director Elaine Adams Frederick Gustin *Brad Piroutek Jenny Aldrich +Natalie Hackler *Julie Piroutek Jamea J. Sale, MME Jean Ayers Jill Hall Melanie Ragan WBCF Executive Associate Music Director *Laura Baker Emerson Hartzler Jane Rockhold *Chris Barnard Kelli Jo Henderson Elizabeth Rowell Lynn Swanson, MME Carolyn Baruch Stephen Hodson Christopher Rupprecht Director, Institute for Healthy Singing *David Beckers Esther Huhn *Jamea Sale Music Director, Baroque Summer Institute Emily Behrmann Beverly Hunt +Shad Sanders *Jennifer Berroth Laura Jacob Charis Schneeberger Andrew Phillip Schmidt, MM Harvey Berwin *Jim Jandt Vicki Schultz Music Director, New South Festival Singers Madeline Boorigie *Jill Jarrett Caren Seaman Music Director-Elect, Summer Singers Atlanta Rebecca Boos *Gary Jarrett *Cindy Sheets Amy Thropp, MM Chris Bradt Susan Johannsen +Pratima Singh Music Director, Zimria Festivale Atlanta Debra Burnes Elaine Johnson Gary Smedile +Mary Burnett Rebecca Jordan Pam Smedile Christine M. Freeman, MME Cynthia Campbell Russell Joy +George Smith Associate Music Director/Senior Vocal Coach *William Cannon Julie Kaplan Linda Spears Becky Carle *Amanda Kimbrough Barton Stanley Scott C. -

Carl Orff Carmina Burana (1937)

CARL ORFF CARMINA BURANA (1937) CARL ORFF CARMINA BURANA (1937) CARMINA: Plural of Carmen, Latin for song. BURANA: Latin for, from Bayern, Bavaria. CANTATA VERSUS ORATORIO: Ø Cantata: A sacred or secular work for chorus and orchestra. Ø Oratorio: An opera without scenery or costumes. THE MUSIC: Ø A collection of 24 songs, most in Latin, some in Middle High German, with a few French words. THE SPECTACLE: Ø Seventy piece orchestra. Ø Large chorus of men, women and boys and girls. Ø Three soloists: tenor, baritone and soprano. THE POETRY: Ø The Medieval Latin poetry of Carmina Burana is in a style called Saturnian that dates back to 200 B.C. It was accented and stressed, used by soldiers on the march, tavern patrons and children at play. Later used by early Christians. Ø While the poems are secular, some are hymn-like. Orff’s arrangements highlight this. Ø The poems were composed by 13th century Goliards, Medieval itinerant street poets who lived by their wits, going from town to town, entertaining people for a few coins. Many were ex monks or university drop-outs. Ø Common Goliard themes include disaffection with society, mockery of the church, carnal desire and love. Ø Benedictine monks in a Bavarian monastery, founded in 733 in Beuern, in the Alps south of Munich, collected these Goliardic poems. Ø After the dissolution of the monastery in 1803, some two hundred of these poems were published in 1847 by Andreas Schmeller, a dialect scholar, in an anthology that he labeled Carmina Burana. Ø Orff discovered these in 1935 and, with the help of the poet Michael Hoffman, organized twenty-four poems from the collection into a libretto by the same name. -

Carmina Burana

JANÁČKOVA AKADEMIE MÚZICKÝCH UMĚNÍ V BRNĚ Hudební fakulta Katedra kompozice, dirigování a operní režie Studijní obor Dirigování orchestru Carl Orff: Carmina Burana Diplomová práce Autor práce: MgA. Marek Prášil Vedoucí práce: prof. Mgr. Jan Zbavitel Oponent práce: doc. Mgr. Emil Skoták Brno 2017 Bibliografický záznam PRÁŠIL, Marek. Carl Orff: Carmina Burana [Carl Orff: Carmina Burana]. Brno: Janáčkova akademie múzických umění v Brně, Hudební Fakulta, Katedra kompozice, dirigování a operní režie, rok 2017, s.58 Vedoucí diplomové práce prof. Mgr. Jan Zbavitel. Anotace Diplomová práce „Carl Orff: Carmina Burana“, jak již ze samotného názvu vyplývá, pojednává o skladateli Carlu Orffovi a jeho nejslavnější skladbě, kantátě Carmina Burana. V první části shrnuje život skladatele, stručně charakterizuje jeho dílo a kompoziční styl. Druhá část, věnovaná samotné kantátě, je zaměřena především na srovnání několika verzí kantáty. Jedná se o původní originální symfonickou verzi, autorizovanou komorní verzi, a pak také o transkripci pro symfonický dechový orchestr. Annotation The thesis „Carl Orff: Carmina Burana” deals with composer Carl Orff and his most famous composition the cantata of Carmina Burana, as is already clear from the title itself. In the first part the composer's life is summarized and briefly his work and compositional style are characterized. The second part is dedicated to the cantata itself, it is focused on comparing several versions of the cantatas. There is one original symphonic version, the Authorized chamber version, and a transcription for symphonic band. Klíčová slova Carl Orff, Carmina Burana, kantáta, symfonický orchestr, dechový orchestr, komorní ansámbl Keywords Carl Orff, Carmina Burana, cantata, symphonic orchestra, wind band (concert band), chamber ensemble Poděkování Na tomto místě bych rád poděkoval především MgA. -

Concert: Carmina Burana by Carl Orff Ithaca College Choral Union

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 4-17-2005 Concert: Carmina Burana by Carl Orff Ithaca College Choral Union Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra Lawrence Doebler Jeffrey Grogan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ithaca College Choral Union; Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra; Doebler, Lawrence; and Grogan, Jeffrey, "Concert: Carmina Burana by Carl Orff" (2005). All Concert & Recital Programs. 4790. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/4790 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. ITHACA COLLEGE CHORAL UNION ITHACA COLLEGE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Lawrence Doebler, conductor CARMINA BURANA by Carl Orff Randie Blooding, baritone Deborah Montgomery-Cove, soprano Carl Johengen, tenor Ithaca College Women's Chorale, Janet Galvan, conductor Ithaca College Chorus, Janet Galvan, conductor Ithaca College Choir, Lawrence Doebler, conductor Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra, Jeffrey Grogan, conductor Charis Dimaris and Read Gainsford, pianists Members of the Ithaca Children's Choir Community School of Music and Arts Janet Galvan, artistic director Verna Brummett, conductor Ford Hall Sunday, April 17, 2005 4:00 p.m. ITHACA THE OVERTURE TO THE SCHOOL FOR SCANDAL Samuel Barber Ithaca College Symphony -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 128, 2008-2009

* BOSTON SYAfl PHONY m ORCHESTRA i i , V SEASON f '0* 3' Music Director lk Conductor j Emei {Music Director Lc I IP the Clarendon BACK BAY The Way to Live ;; III! in"! I II !! U nil * I v l iji HI I etc - I y=- • ^ Fi 2 '\ i ra % m 1 1 ih ... >'? & !W ||RBIK;| 4* i :: it n w* n- I II " n ||| IJH ? iu u. I 1?: iiir iu» !! i; !l! Hi \m SL • i= ! - I m, - ! | || L ' RENDERING BY NEOSCAPE INTRODUCING FIVE STAR LIVING™ WITH UNPRECEDENTED SERVICES AND AMENITIES DESIGNED BY ROBERT A.M. STERN ARCHITECTS, LLP ONE TO FOUR BEDROOM LUXURY CONDOMINIUM RESIDENCES STARTING ON THE 15TH FLOOI CORNER OF CLARENDON AND STUART STREETS THE CLARENDON SALES AND DESIGN GALLERY, 14 NEWBURY STREET, BOSTON, MA 617.267.4001 www.theclarendonbackbay.com BRELATED DL/aLcomp/ REGISTERED W "HE U.S. GREEN BUILDING COUNl ITH ANTICIPATED LEED SILVER CERTIFICATION The artist's rendering shown may not be representative of the building. The features described and depicted herein are based upon current development plans, which a described. No Fede: subject to change without notice. No guarantee is made that said features will be built, or, if built, will be of the same type, size, or nature as depicted or where prohibited. agency has judged the merits or value, if any, of this property. This is not an offer where registration is required prior to any offer being made. Void Table of Contents | Week 7 15 BSO NEWS 21 ON DISPLAY IN SYMPHONY HALL 23 BSO MUSIC DIRECTOR JAMES LEVINE 26 THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 31 THIS WEEK'S PROGRAM Notes on the Program 35 The Original Sound of the "Carmina burana" (c.1230) 41 Carl Orff's "Carmina burana" 53 To Read and Hear More.. -

Wolfgang Sawallisch Paco 044 Paco 044 Carmina Burana Agnes Giebeliebel - Marcel Cordes - Paul Kuén

L CARL ORFF L WOLFGANG SAWALLISCH PACO 044 PACO 044 CARMINA BURANA AGNES GIEBELIEBEL - MARCEL CORDES - PAUL KUÉN 1 Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi - i: O Fortuna (2:43) 2 Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi - ii: Fortune plango vulnera (2:41) 3 I – Primo vere - iii: Veris leta facies (3:25) 4 I – Primo vere - iv: Omnia sol temperat (2:04) 5 I – Primo vere - v: Ecce gratum (2:35) 6 Uf dem Anger - vi: Tanz (1:47) 7 Uf dem Anger - vii: Floret Silva (3:13) 8 Uf dem Anger - viii: Chramer, gip die varwe mir (3:06) 9 Uf dem Anger - ix. Reie - Swaz hie gat umbe - Chume, chum, geselle min (4:22) A Uf dem Anger - x: Were diu werlt alle min (0:52) B II – In Taberna - xi: Estuans interius (2:25) C II – In Taberna - xii: Olim lacus colueram (3:11) D II – In Taberna - xiii: Ego sum abbas (1:34) Agnes Giebel, soprano E II – In Taberna - xiv: In taberna quando sumus (3:08) Marcel Cordes, baritone F III – Cour d'amours - xv: Amor volat undique (3:13) Paul Kuén, tenor G III – Cour d'amours - xvi: Dies, nox et omnia (2:17) H III – Cour d'amours - xvii: Stetit puella (1:49) Chorus of the Westdeustchen Rundfunk I III – Cour d'amours - xviii: Circa mea pectora (2:03) Chorus-master: Bernhard Zimmerman J III – Cour d'amours - xix: Si puer cum puellula (0:56) K III – Cour d'amours - xx: Veni, veni, venias (0:57) Cologne Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester L III – Cour d'amours - xxi: In trutina (1:48) conductor Wolfgang Sawallisch M III – Cour d'amours - xxii: Tempus est iocundum (2:06) N III – Cour d'amours - xxiii: Dulcissime (0:36) Recorded in 1956 under the personal O Blanziflor et Helena - xxiv: Ave formosissima (1:42) supervision of Carl Orff P Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi - xxv: O Fortuna (reprise) (2:38) ORFF - CARMINA BURANA Transfer from UK Columbia LP 33CX1480 in the Pristine Audio collection R 1956 C O XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, May 2010 ECORDED ININ UNDER THE PERSONAL SUPERVISION OF ARL RFF Cover artwork based on a photograph of Wolfgang Sawallisch C W R Total duration: 57:11 ©2010 Pristine Audio. -

Reconsidering the Carmina Burana Gundela Bobeth (Translated by Henry Hope)1

4 | Wine, women, and song? Reconsidering the Carmina Burana gundela bobeth (translated by henry hope)1 Introduction: blending popular views and scientific approaches By choosing the catchy title Carmina Burana –‘songs from Benediktbeuern’–for his 1847 publication of all Latin and German poems from a thirteenth-century manuscript held at the Kurfürstliche Hof- und Staatsbibliothek Munich, a manuscript as exciting then as now, the librar- ian Johann Andreas Schmeller coined a term which, unto the present day, is generally held to denote secular music-making of the Middle Ages in paradigmatic manner.2 The Carmina Burana may be numbered among the few cornerstones of medieval music history which are known, at least by name, to a broader public beyond the realms of musicology and medieval history, and which have evolved into a ‘living cultural heritage of the present’.3 Held today at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek under shelfmarks Clm 4660 and 4660a, and commonly known as the ‘Codex Buranus’, the manuscript – referred to in what follows as D-Mbs Clm 4660-4660a – constitutes the largest anthology of secular lyrics in medieval Latin and counts among the most frequently studied manuscripts of the Middle Ages.4 Yet the entity most commonly associated with the title Carmina Burana has only little to do with the musical transmission of this manu- script. Carl Orff’s eponymous cantata of 1937, which quickly became one of the most famous choral works of the twentieth century, generally tops the list of associations. Orff’s cantata relates to D-Mbs Clm 4660-4660a only in as much as it is based on a subjective selection of the texts edited by Schmeller; it does not claim to emulate the medieval melodies. -

Carmina Burana

Carmina Burana Featuring the Choir and Percussion Ensembles of the Department of Music at the Université de Moncton; Monique Richard, conductor; Indian River Festival Chorus; Kelsea McLean, conductor; Danika Lorèn, soprano; Jonathan MacArthur, tenor; Adam Harris, baritone; Peter Tiefenbach, piano; and Robert Kortgaard, piano Sunday, July 10, 7:30pm Fogarty’s Cover Stan Rogers, arr. by Ron Smail I Dreamed of Rain Jan Garrett, arr. by Larry Nickel Praise His Holy Name Keith Hampton Embarquement pour Cythere Francis Poulenc Catching Shadows Ivan Trevino Misa Criolla Ariel Ramirez INTERMISSION Carmina Burana Carl Orff Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi Fortune, Empress of the World 1. O Fortuna O Fortune 2. Fortune plango vulnera I lament the wounds that Fortune deals I. Primo vere In Spring 3. Veris leta facies The joyous face of Spring 4. Omnia Sol temperat All things are tempered by the Sun 5. Ecce gratum Behold the welcome Uf dem anger In the Meadow 6. Tanz Dance 7. Floret silva The forest flowers 8. Chramer, gip die varwe mir Monger, give me coloured paint 9. a) Reie Round dance b) Swaz hie gat umbe They who here go dancing around c) Chume, chum, geselle min Come, come, my dear companion d) Swaz hie gat umbe (reprise) They who here go dancing around 10. Were diu werlt alle min If the whole world were but mine II. In Taberna In the Tavern 11. Estuans interius Seething inside 12. Olim lacus colueram Once I swam in lakes 13. Ego sum abbas Cucaniensis I am the abbot of Cockaigne 14. In taberna quando sumus When we are in the tavern III. -

Naxos Catalog (May

CONTENTS Foreword by Klaus Heymann . 3 Alphabetical List of Works by Composer . 5 Collections . 95 Alphorn 96 Easy Listening 113 Operetta 125 American Classics 96 Flute 116 Orchestral 125 American Jewish Music 96 Funeral Music 117 Organ 128 Ballet 96 Glass Harmonica 117 Piano 129 Baroque 97 Guitar 117 Russian 131 Bassoon 98 Gypsy 119 Samplers 131 Best Of series 98 Harp 119 Saxophone 132 British Music 101 Harpsichord 120 Timpani 132 Cello 101 Horn 120 Trombone 132 Chamber Music 102 Light Classics 120 Tuba 133 Chill With 102 Lute 121 Trumpet 133 Christmas 103 Music for Meditation 121 Viennese 133 Cinema Classics 105 Oboe 121 Violin 133 Clarinet 109 Ondes Martenot 122 Vocal and Choral 134 Early Music 109 Operatic 122 Wedding Music 137 Wind 137 Naxos Historical . 138 Naxos Nostalgia . 152 Naxos Jazz Legends . 154 Naxos Musicals . 156 Naxos Blues Legends . 156 Naxos Folk Legends . 156 Naxos Gospel Legends . 156 Naxos Jazz . 157 Naxos World . 158 Naxos Educational . 158 Naxos Super Audio CD . 159 Naxos DVD Audio . 160 Naxos DVD . 160 List of Naxos Distributors . 161 Naxos Website: www.naxos.com Symbols used in this catalogue # New release not listed in 2005 Catalogue $ Recording scheduled to be released before 31 March, 2006 † Please note that not all titles are available in all territories. Check with your local distributor for availability. 2 Also available on Mini-Disc (MD)(7.XXXXXX) Reviews and Ratings Over the years, Naxos recordings have received outstanding critical acclaim in virtually every specialized and general-interest publication around the world. In this catalogue we are only listing ratings which summarize a more detailed review in a single number or a single rating. -

“O Fortuna” from Carl Orff's Carmina Burana Movement Idea by Cristi Cary Miller

“O Fortuna” from Carl Orff's Carmina Burana Movement Idea by Cristi Cary Miller May be used with the listening lesson for “O Fortuna” from Carmina Burana by Carl Orff in the October/November 2010, Volume 11, No. 2 issue of Music Express. Formation: Partners forming concentric circles, inside circle facing outward. Each dancer holds a scarf in right hand. INTRO “O Fortuna”: Outside circle slowly raises scarf in the air and waves it R/L. “Velut luna”: Inside circle repeats action. “Statu variabilis”: With arms still raised above head, partners circle each other CW and return to starting position, facing to their R. SECTION ONE Line 1 Beats 1-6: Circles walk to their R (inside CCW, outside CW), waving scarves downward L/R on the beats. Beats 7-12: All turn in place with scarves in air. Line 2 Beats 1-6: Repeat above going in opposite direction and back to part- ners. Beats 7-12: All turn in place with scarves in air. Line 3 Beats 1-12: Circles walk to their R, waving scarves downward L/R on the beats, stopping at partners on opposite side of circle. SECTION TWO Line 1 Beats 1-6: Outside circle only walks to their R, waving scarves down- ward L/R on the beats; inside circle stays in place. Beats 7-12: Outside circle dancers turn in place with scarves in the air and hold position. Line 2 Beats 1-6: Inside circle only walks to their R, waving scarves downward L/R on the beats; outside circle stays in place. -

Of Music PROGRAM

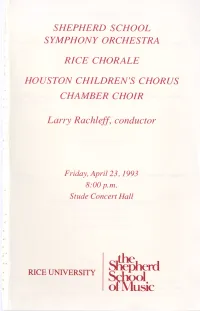

SHEPHERD SCHOOL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICE CHORALE HOUSTON CHILDREN'S CHORUS CHAMBER CHOIR Larry Rachleff, conductor Friday, April23, 1993 8:00p.m. Stude Concert Hall "-' sfkteherd RICE UNIVERSITY Sc~ol Of Music PROGRAM Fanfare for a Great City Arthur Gottschalk (b. 1952) Variations on a Theme of Joseph Haydn, Op. 56a Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) INTERMISSION Carmina Burana Carl Orff ( 1895-1982) Rice Chorale Houston Children's Chorus Chamber Choir Kelley Cooksey, soprano Francisco Almanza, tenor Robert Ames, baritone In consideration of the performers and members of the audience, please check audible paging devices with the ushers and silence audible timepieces. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are prohibited. SHEPHERD SCHOOL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Violin I Viola (cont.) Oboe Trumpet (cont.) Julie Savignon, Erwin Foubert Margaret Butler Troy Rowley concertmaster Patrick Horn Kyle Bruckmann David Workman Claudia Harrison Stephanie Griffin Jeffrey Champion Trombone Barbara Wittenberg Bin Sun Dione Chandler Wade Demmert Jeanine Tiemeyer Andrew Weaver Karen Friedman David Ford Kristin Lacey Sharon Neufeld ~ Brent Phillips Mihaela Oancea English Horn Cello Kyle Bruckmann Inga Ingver Tuba Katherine de Bethune, Yenn Chwen Er Clarinet Jeffrey Tomberg principal Yoong-han Chan Benjamin Brady Danny Urban ~ Jeanne Jaubert Magdalena Villegas Joanne Court Scott Brady Timpani and Tanya Schreiber Kelly Cramm Mary Ellen Morris Percussion Rebecca Ansel Martin van Maanen Robin Creighton Douglas Cardwell Eitan Ornoy X in-Yang Zhou Amy